Seeking the truth behind the tragedy of JFK’s assassination

B

arb Junkkarinen emerges from the bedroom with the gift her husband and son gave her one Christmas.

It’s a 1940 Italian-made rifle, like the one Lee Harvey Oswald fired from a sixth-floor window at the Texas School Book Depository, killing President Kennedy on an autumn afternoon in Dallas. He’d spirited the weapon into the building by disguising it as a curtain rod.

“This is how Oswald carried his package,” she says, holding the butt of the rifle low, the way witnesses described. “He had it cupped in his hand, like this.”

Junkkarinen’s husband, Juha, and son, Jason, nod at the demonstration they’ve seen again and again. They help adjust the unloaded weapon just so. They point out there’s also a scope and ammunition.

Over more than half her lifetime, Barb Junkkarinen has made a hobby of delving into rumors, theories and contradictory facts that swirl around a killing that continues to titillate — and divide — Americans on the 50th anniversary of the events of Nov. 22, 1963.

In the world of online Kennedy discussion groups, she learned “lurkers” tune in but never post; “fringies” attribute a political motive to every turn; false witnesses claim to have been places they haven’t. Those who believe Oswald acted alone are “lone-nutters.”

And people like Junkkarinen are CTs, for conspiracy theorists.

She has amassed a trove of artifacts: autopsy reports, investigation documents, shelves of books and photos, and a model of the Lincoln Continental limousine Kennedy rode in when he was shot in Dealey Plaza. There’s also a life-sized plastic model of a human skull she uses to make detailed arguments about bullet entry and exit.

Inside her Portland-area home office, she avidly dissects the latest theories of the paranoid and the emotionally unstable.

They include those who believe Kennedy was first hit in the throat with a bullet made of ice; that a man in Dealey Plaza fatally wounded the president with a dart fired from an umbrella; and that J. Edgar Hoover attended a party the night before the assassination celebrating JFK’s imminent demise.

Junkkarinen rejects those theories. She blames gangsters and spies.

Junkkarinen, 62, can still picture where she heard the news: She was 12 years old, a seventh-grader sitting in the second seat in the row by the window at a Catholic school in San Diego. A superior whispered into the ear of her teacher, whose freckled face instantly turned red.

The nuns instructed students to say Hail Marys on Kennedy’s behalf. Later, after Oswald was shot by Jack Ruby, Junkkarinen heard her father say, “Something’s just not right here.”

She recalls thinking: “Nothing’s right about any of it, Dad.”

By age 15, she’d read the lengthy report published by the Warren Commission, which had conducted the investigation of the killing. She graduated high school and studied to become a medical laboratory technician. She married Juha and moved to Oregon. She would read each new book that purported to solve the Kennedy assassination.

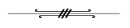

Seconds after the fatal shot, a Secret Service agent climbs aboard the president’s limousine as the first lady, her husband slumped over in the backseat, crawls onto the trunk lid. (Ike Altgens / Associated Press) More photos

The year 1980 brought a turning point: “Best Evidence: Disguise and Deception in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy” by David Lifton, which focused on medical evidence she understood, with descriptions from attending doctors on the locations of JFK’s wounds. Junkkarinen checked it out of the library and read it three times.

She eventually dismissed Lifton’s central premise — that the president’s body had been altered to suggest gunshots fired from the rear, as a way to help prove the government’s argument that Oswald alone killed JFK. But the book led her to pursue theories of her own.

Junkkarinen came to believe JFK’s death was not the result of a lone killer, a view shared by many. A nationwide Associated Press-GfK poll of 1,004 adults in April found that 59% thought multiple people participated in a conspiracy to kill Kennedy, while 24% thought Oswald acted alone. About 16% were unsure.

Junkkarinen argues there were two conspiracies.

The point is not to say ‘I got it!’ We simply want to know the truth.”

— Barb Junkkarinen

The first, she says, involved a network of gangsters or spies who executed the killing. The second was a coverup by Cold War-era government officials convinced that Americans were incapable of understanding how such a network could assassinate the president.

A lawyer who has written a book about conspiracies says such theories apply a sensible narrative to troubling historical puzzles like the Kennedy killing, which was the first to mesmerize the entire nation on television.

“There’s the suggestion everything changed after the JFK assassination,” says Mark Fenster, author of “Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture.”

And the hero in any conspiracy narrative, says Fenster: “The person who solves the puzzle.”

Junkkarinen says she’s not trying to be a hero. “We work quietly and diligently,” she says. “The point is not to say ‘I got it!’ We simply want to know the truth.”

Junkkarinen’s research has taken her to Kennedy archives and to Dealey Plaza. She speaks at conferences and advises fellow conspiracy theorists on their theories.

“In a field known for hysterics, Barb is grounded,” said Josiah Thompson, a fellow conspiracy theorist and author of the 1967 book “Six Seconds in Dallas.” Thompson is a former Yale philosophy professor who became a private investigator.

“She patrols down the center of the freeway of reasoned debate on this topic,” he said, “pointing out all the nuttiness along the way.”

In one paper published by a group devoted to Kennedy assassination followers, Junkkarinen explains that the small gadgets found in Dealey Plaza today are not government eavesdropping devices, as an online poster claimed, but water sprinkler sensors.

Junkkarinen’s family and friends have supported her work. Both husband and son have served as presidential stand-ins, lying atop a gurney with a taped-on plastic wound, when she needed a model for presentations with titles such as “The Back of Kennedy’s Head.”

During one talk at her home, friends flinched when she produced the autopsy photos. A psychologist had trouble sleeping for weeks.

“I guess she didn’t realize all that goes into an autopsy,” Junkkarinen says.

Sitting at her desk, Junkkarinen surveys half a dozen storage boxes of Kennedy materials spread across the floor.

“Now, where is that skull?” she says of the item she ordered from a medical supply company. She says it provides context, like the carbine.

When Junkkarinen got the Oswald rifle, her mother asked, “What do you want with that? Let the man be dead.”

Junkkarinen took the rifle, widely known as a Mannlicher-Carcano, to a shooting range and fired it. The weapon “kicks like a mule,” she says. While she believes Oswald carried the gun into the book depository, she calls him a pawn and theorizes he never fired the weapon that day.

She says shooting the rifle has bolstered her contention that it could not have been fired three times in just seconds, as the government claims. “That’s my approach,” she says. “I want to see and hold things for myself.”

She never finds the skull but shows off a gift from Jason — a mock front page from the satirical publication the Onion with the headline: “Kennedy Slain by CIA, Mafia, Castro, LBJ, Teamsters, Freemasons: President shot 129 times from 43 different angles.”

Junkkarinen smiles. She gets the humor.

Like the late-night phone call from a woman with a cigarette-tinged voice: “I just want you to know you’re right,” she whispered, “and I can prove it.” Or the day Jason, now 26, came home from school with a question from his teacher, Sister Mary Ann:

“Why would a second-grader be able to spell the word ‘assassination’?”

Follow John M. Glionna (@jglionna) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter