Something in the water: is fluoride actually good for cities?

As a public health researcher who examines sensitive subjects such as sexual health and teenage pregnancy, Stephen Peckham is used to robust debate.

But when his research questioned whether cities should be adding fluoride to their drinking water, Peckham, director of the Centre for Health Service Studies at the University of Kent and a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the University of Toronto, wasn’t ready for the poisonous attacks that followed.

“Nothing prepared me for the ferocity around fluoridation,” says Peckham. Over a 25-year academic career he has written or co-authored more than 150 papers, chapters and books. His work is cited in another 1,300 papers. Yet his research on water fluoridation will not, he has been told, be published in the main dental health journals.

When Scientific World published his paper on ingested fluoride in 2014, the journal was dismissed as “shonky” and a “bottom-feeder”. When the more reputable peer-reviewed Journal of Epidemiological and Community Health published Peckham’s research on fluoride and hypothyroidism last year, one dental school professor said that it “beggars belief that they should be able to say that in a reputable publication”, while a professor of medicine said it was “irresponsible for the paper’s peer reviewers to not have asked the authors to tone down their conclusions”. Science blogs accused him of “statistics-hacking” and cited him as an example of “how to lie with statistics”.

“It’s very difficult,” Peckham says. “I’ve been hugely and personally attacked by scientific bloggers in different countries. But that’s the difficulty of trying to work in this area, so I just keep my head down.”

<!–[if IE 9]>

<!–[if IE 9]><![endif]–>

Anti-fluoride protesters in Minneapolis in 2014. Photograph: Alamy

Even the history of water fluoridation is a toxic subject, as Catherine Carstairs, a professor at the University of Guelph in Ontario, recently discovered. Carstairs was taken aback by the “fierceness” of the responses to her paper in the American Journal of Public Health last year. It was attacked as “an attempt to reignite and legitimise the unsubstantiated claims of anti-fluoridationists”. The journal’s editor was forced to defend his decision to publish “an article that does not unconditionally support community water fluoridation or its glorious history”, as well as the journal’s right “to publish strong pieces of research even when they do not fit well with our preconceived ideas”.

“You don’t usually get this kind of attention as an historian,” says Carstairs. “It was like, how dare you say anything against water fluoridation.”

Social media has inured us to the bloodsport of “calling out” or “shutting down” opponents whose views are unorthodox or contrarian. But the people calling out Carstairs and Peckham were university academics, not bedroom-residing teenagers.

Tooth decay is the most widespread chronic disease in cities. It is also the most common childhood disease. Untreated tooth decay plagues up to seven in 10 children in India, one in three teenagers in Tanzania and almost one in three adults in Brazil. If untreated, dental caries can lead to tooth loss, chewing problems, malnutrition and infection. In the UK in the three years to 2014, the number of admissions for dental problems among children between five and nine rose almost 15%, to 25,812.

More than half a century since it became a default, however, the adding of fluoride to drinking water has become no less contentious – and for a public health intervention of this scale to lack the killer evidence to convince doubters is unprecedented. In Newcastle, where I live, the drinking water has been fluoridated for almost 50 years. Yet just 100 miles away in Hull – a city of similar size, demographics and health indicators – the city council is steeling itself for another attempt at convincing sceptical citizens who rejected fluoridation plans a decade ago.

The story of the two cities is instructive. More than 60 years after the first water fluoridation schemes, cities across the world remain locked in a binary debate about whether or not to fluoridate, a debate polarised by near-religious fervour and loaded terms: “mass medicaters” on one side, “conspiracists”, “truthers” and “deniers” on the other.

Fluoride in Newcastle …

<!–[if IE 9]>

<!–[if IE 9]><![endif]–>

Modern equipment for adding fluoride to mains water supplies. Photograph: Alamy

Most of our drinking water in Newcastle comes from reservoirs at Whittle Dene, Northumberland, guarded by the ghosts of a Roman milecastle on Hadrian’s Wall. At the adjoining water treatment works, Northumbrian Water manager David McDermott tells me he is due another tanker delivery of hexafluorosilicic acid, which will be used to fluoridate the water supply to Newcastle and the rest of Tyneside.

It’s an extremely corrosive chemical in neat form. Without a protective suit and boots, I am not permitted to step within 10ft of the three 10,000-litre tanks that hold the acid.

Extracted from Spanish phosphate rock and converted by Essex manufacturer Industrial Chemicals, around 600 litres of hexafluorosilicic acid is added here every day, at the same final stage of the water treatment process as chlorine (to disinfect) and phosphoric acid (to counteract lead in the supply pipes). Algorithms and transfer pumps ensure the fluoride leaves at the mandated level of one part per million (1ppm) parts of water.

<!–[if IE 9]>

<!–[if IE 9]><![endif]–>

Used industrially in the manufacture of ceramics, pesticides and Teflon cookware, fluoride is generally an unwanted byproduct of the manufacture of aluminium, fertiliser and iron ore. But its impact on teeth was recognised in 1909 in Colorado when two dental surgeons, Frederick McKay and Grant Black, began questioning the causes of mottled enamel in their practice area. Further studies in Idaho and Arkansas confirmed a link with high water fluoride levels, and in the 1940s scientists at the National Institute of Health found that water containing fluoride at a concentration of 1ppm appeared to offer some caries protection while minimising the extent of dental fluorosis.

It’s widely accepted that long-term ingestion of large amounts of fluoride can lead to potentially severe skeletal fluorosis. In India for example, high naturally occurring fluoride content in drinking water is blamed for the fluorosis that has crippled around six million people. Compared to the 1ppm limit on artificially fluoridated water in my city, naturally occurring concentrations of up to 38.5ppm have been reported in some parts of India.

Whittle Dene’s dosing equipment was upgraded 10 years ago, but in essence fluoride has been added in this way since 1968. Around 40% of Northumbrian Water’s 2.5 million customers receive artificially fluoridated water in Newcastle, Gateshead, parts of Durham, Hexham and north Northumberland. Other areas – mainly the east coast – have naturally occurring high levels of fluoride in water. Alan Brown, water quality manager for Northumbrian Water, says the cost of fluoridation is met fully by the taxpayer. “We just do what we’re asked to do,” he says.

… silence in Hull

It seemed a reasonable enough question. Could I speak to someone at Hull City council about its plans – supported by former health secretary and local MP Alan Johnson – to introduce fluoride to the water supply? After all, despite more than 60 proposals, all of which were backed by strong support from government, the dental profession and public health experts, no new fluoridation schemes (aside from a limited extension in the West Midlands) have been passed in the UK in the last 20 years.

Hull has a terrible record in tooth decay in young children. The British Dental Association says 43% of the city’s five-year-olds suffer tooth decay, compared with 28% nationally. General anaesthetic is applied more frequently to children in Hull having decayed teeth removed than for any other reason.

The chief proposer of plans to fluoridate in Hull is Colin Inglis, the chair of the city’s health and wellbeing board. He has the support of the local dental committee – it was they who approached him via Alan Johnson – as well as the local medical committee, the British Dental Association, the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry and the British Medical Association. But the plans and subsequent backlash from locals have filled local newspaper pages for months.

<!–[if IE 9]>

<!–[if IE 9]><![endif]–>

Dr Frederick McKay, who helped discover fluoride’s impact on teeth in Colorado in 1909, explains fluoride to a young patient. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

My requests to the council’s press office to visit and meet with councillors or officials to discuss the consultation into fluoridation were all denied or ignored. Hull city council has commissioned an engineering feasibility study on fluoridation from Yorkshire Water, after which it will decide how and whether to proceed. Until then, no money is allocated for the capital costs of fluoridation or public consultation.

Local supply teacher and Green party chair for Hull, Martin Deane, will be ready if and when the consultation is relaunched. At a table in an independent coffee shop near Hull train station, he passes me some hand-outs he has prepared. They list the dangers of water fluoridation and tease possible links between ingested fluoride and a wide range of health conditions.

The hand-outs include a graph, compiled from World Health Organisation figures, that suggests the improving dental health in 18 different countries has had little to do with whether or not they adopted water fluoridation. Deane’s notes quote a report by the US Environmental Protection Agency that described fluoride as a “developmental neurotoxin”: Deane has concluded that it’s bad for embryos, babies and infants. There’s a reminder at the end of the handout not to forget how scientists have got it wrong in the past: lead in paints and petrol; asbestos; tobacco; a sleeping pill called thalidomide.

Deane, who has stopped using fluoride toothpastes, says he recently complained to a head teacher after he saw a visiting dental nurse tell pupils it was OK to swallow toothpaste.

“Water fluoridation is religion rather than good science,” says Deane, who joined the Green party the last time fluoridation was on the agenda, in 2005. “It’s mass medication, with no control of dose as there’s no control over how much water one person will drink in any given day. And since 96% of the water supplied is not drunk, that’s a waste of 96% of the money spent on fluoridation.”

The most recent plans to fluoridate a city’s water, in Southampton, were debated for five years before being abandoned, despite being endorsed by Public Health England and a high court ruling in 2014. The UK government continues to back mass fluoridation of tap water to cut tooth decay – yet as recently as February, the health minister responsible for dentistry, Alistair Burt, said he was “perfectly convinced by the science”, but admitted that MPs will never vote for it.

To add or not to add?

Should we be perfectly convinced by the science? I’ve had more fillings than I can remember. Northern Ireland, where I grew up, is known as the UK’s childhood tooth decay capital, with 72% of 15-year-olds suffering oral disease. In Wales that figure is 63%. In England, just 44%.

Northern Ireland does not add fluoride to its drinking water. Nor does Wales. But England does, with around 5.8 million receiving artificially fluoridated water at the 1ppm concentration.

Round one to water fluoridation? The first major scheme was in Birmingham in 1964. Since then parts of the north-west, north-east, Yorkshire and the Humber have followed suit, as have large swathes of the Midlands. I ask my dentist, as he’s applying a fluoride varnish to my nine-year-old’s teeth, to describe the experience of dentists in cities that don’t fluoridate their water. “They spend all their time drilling and filling,” he recalls from conversations with colleagues. You won’t find many dentists holding contrarian views.

According to Public Health England, fluoridation is a “safe and effective” public health measure. Its latest study shows that in fluoridated areas, such as Newcastle, there were 45% fewer children aged one to four admitted to hospital. Levels of general tooth decay were 15% lower for five-year-olds and 11% lower for 12-year-olds. The average number of decayed, extracted or filled teeth (known as d3mft) is 0.75 in Newcastle, below the national average of 0.94 and half the figure of 1.54 in Hull, where the water is not artificially fluoridated. In Middlesbrough it’s 1.71, in Manchester 1.78, in Blackpool 1.81.

Children in the London borough of Enfield have the country’s worst teeth, with the average number of decayed, extracted or filled teeth at 2.05. These are all cities and towns where the drinking water is not fluoridated. Round two to water fluoridation?

<!–[if IE 9]>

<!–[if IE 9]><![endif]–>

Yet the best performers, with smallest d3mft figures – towns and cities like Brighton (0.35), Bristol (0.35) and Richmond on Thames (0.4) – are also cities and towns where the drinking water is not fluoridated. Around one million people in Birmingham – the whole of the city’s population – are supplied with artificially fluoridated water. But its d3mft rating is 1.17, higher than the national average. Across the West Midlands, where water has been fluoridated since 1964, there has been a 300% rise in children under the age of 10 being admitted to hospital for multiple teeth extractions in the last five years.

The evidence that water fluoridation achieves anything more than a modest dental caries prevention effect is equivocal. Over the last 15 years, there have been two significant reviews of the research into water fluoridation. In 2001, Professor Trevor Sheldon, chair of the advisory group for a review commissioned by the Department of Health, expressed surprise that in spite of the large number of studies carried out over several decades there was a dearth of reliable evidence with which to inform policy. “Until high-quality studies are undertaken providing more definitive evidence, there will continue to be legitimate scientific controversy over the likely effects and costs of water fluoridation,” he wrote.

And just last year, the Cochrane group, a collaboration of academics who review medical research papers, expressed concerns about the methods used, or the reporting of the results, in 97% of the studies into water fluoridation. Many, it said, did not take full account of all the factors that could affect children’s risk of tooth decay. They also found substantial variation between the results of the studies, many of which took place before the introduction of fluoride toothpaste. “This makes it difficult to be confident of the size of the effects of water fluoridation on tooth decay or the numbers of people likely to have dental fluorosis at different levels of fluoride in the water.”

In the meantime, other reports have flagged up possible links between fluoride and other health conditions, from cognitive impairment and hypothyroidism to depression and skeletal fluorosis.

‘Fluoride allowed dentists to be scientific professionals’

Spain and the Republic of Ireland are the only other European countries with similar levels of fluoridation to Britain. It remains more popular in Australia, Brazil, Chile, Malaysia, Singapore and the US, where water fluoridation retains its strongest hold. Around 194 million Americans are supplied with artificially fluoridated water, including those who live in 43 of its 47 largest cities.

Water fluoridation in the US was aggressively promoted by dentists such as John G Frisch from Madison, Wisconsin, so enamoured by fluoride that he supplied his children with fluoridated water that he mixed at home. When his daughter developed a mild form of dental fluorosis, he eagerly displayed her damaged teeth across the state. Together with Frank Bull, dental health officer at the state board of health, he campaigned for fluoridation across the United States. Scientists at the US Public Health Service were reluctant to endorse water fluoridation in 1950 but were ultimately overwhelmed by pressure from the state dental directors.

Infused with optimism about what postwar science and medicine could accomplish, some dentists and public health officials persuaded the World Health Organization to accept water fluoridation as an effective oral health intervention. The anti-caries effect of fluoride on developing teeth became scientific orthodoxy.

“It was dentists’ first real tool for improving oral health,” says Catherine Carstairs. “Previously they could remove decayed teeth, but nothing that improved people’s dental health over all. Fluorides allowed dentists to be more than fillers and fixers of teeth. They became scientific professionals using tools that had been tested in controlled studies.”

Fluoridation also seemed like a boon, she says, to frustrated dentists who believed that the public could not be trusted to brush their teeth or eat less sugar. “Dentistry is always aware of its second cousin status to medicine, so part of their strong defence of fluoridation comes from that professional insecurity,” she argues. “But part of it also comes from their passion for preventing children from unnecessary suffering, so the anti-fluoridation movement drives them crazy.”

The early opponents of fluoridation came, largely, from the libertarian right. Film director Stanley Kubrick parodied them in his 1964 movie Dr Strangelove, in which Peter Sellers’ character Mandrake is warned that “fluoridation is the most monstrously conceived and dangerous Communist plot we have ever had to face”. Other wild conspiracy theories have included suggestions that water fluoridation was used in Nazi concentration camps.

While Carstairs believes water fluoridation did improve the dental health of many children in the 60s and 70s, she thinks fluoride proponents were too hasty in declaring it the only solution for dental decay. “To come out as being uncertain about fluoridation was not a good career move for dentists for much of the 20th century,” she says.

Likewise, the academic community has been too hasty to brandish opponents to water fluoridation as mad or unscientific, says Stephen Peckham. Even internationally respected scientists and academics have consistently found it difficult to publish critical articles of water fluoridation in scholarly dental and public health journals, he argues.

Fluoridation’s longstanding status as a national public health policy makes governments reluctant to question it. “If you’re running a public health programme, it’s a big decision to stop it and admit you were wrong,” says Peckham. “To maintain confidence in your public health programmes, you’ve got to continue projecting a positive message.” Peckham describes how Public Health England “did a demolition job” on a recent paper in which he suggested hypothyroidism was higher in areas that were fluoridated.

“I’d like to do more to research to unpick that association, and it’s the sort of thing the Department of Health should be funding,” he says. “But that would be very unlikely given that it is promoting water fluoridation.”

Canadian caries

But the enthusiasm with which water fluoridation was introduced as a public health measure in the 1950s may now be giving way to a more rational analysis of its benefits and costs, especially as cities battle to address a wide range of health issues with squeezed budgets.

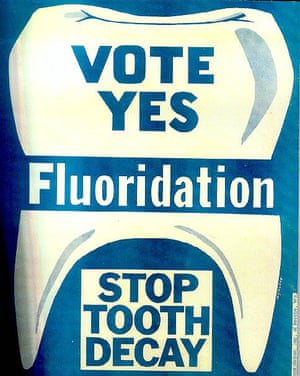

<!–[if IE 9]>

<!–[if IE 9]><![endif]–>

A US department of health poster advertising the benefits of fluoride. Photograph: Alamy

In recent years, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland have stepped back from fluoridating their water supplies. The latest fluoride-in-water fight is in Canada, where 14 million people are supplied with artificially fluoridated water. Some cities, including Calgary, Quebec City, Waterloo, Windsor and Saint John, have begun removing fluoride from their public drinking water – even as a study in Calgary just published by the city’s university shows tooth decay in children has worsened since the city stopped fluoridation in 2011.

Elsewhere, cities are receiving direction from above: in Israel in 2013, for example, the minister for health announced the end of mandatory water fluoridation. The US, Canada and Republic of Ireland have reduced dosage levels to 0.7ppm. And when Britain’s Health and Social Care Act came into force in 2013, the decision-making for water fluoridation passed from the strategic health authorities to local authorities. It was a necessary separation, says Peckham: “The strategic health authorities were both arbiter and promoter of water fluoridation. Now we need to ensure cities and councils have a proper and balanced debate placed in front of them.”

Easier said than done. Since the University of Calgary study found that the city’s second graders now have, on average, 6.4 instances of tooth decay compared with 2.6 a decade ago, Calgary mayor Naheed Nenshi has come out in favour of re-fluoridation and is urging people to petition for a plebiscite in the 2017 municipal election.

In fact, the increase in cavities seen in Calgary may be part of a larger trend. Tooth decay in baby teeth has actually been on the rise since the 1990s throughout North America, including in fluoridated cities like Edmonton, Calgary’s provincial rival. According to Professor Trevor Sheldon’s critique of the Calgary study, it shows a higher average annual rate of increase in tooth decay in the period before cessation (7%) than in the period which includes years after cessation (5%). “This is contrary to what one would expect if fluoridation cessation was the primary driver of increases in caries over the period,” he says.

But reasoned debate on facts may prove elusive. Tom Flanagan, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary, has already stoked the flames by describing opposition to fluoridation in the city as “part of the repertoire of the technophobic, chemophobic left, along with hostility to vaccination and genetically modified foods, and attraction to homeopathy, naturopathy and other forms of alternative medicine.”

A fluoride-free future?

As a young dentist, Lorna MacPherson had to extract the teeth of young children under general anaesthetic. “It was always difficult to see the pain they were experiencing,” she recalls.” She sees a different picture now when she visits nurseries in Glasgow to measure the oral health of three-year-olds. “Ten years ago the nursery teachers would show us children with black or no front teeth. Now we see rows of lovely white teeth. It makes our work so rewarding.”

A decade ago, Scotland’s chief dental officer asked MacPherson, a professor of public dental health at the University of Glasgow, to pilot an alternative to water fluoridation. And since 2010, her Childsmile initiative has been rolled out across the country, giving young children free toothbrushes, toothpaste and two fluoride varnish applications per year. Children attending nursery, and those in primary schools in deprived areas, are offered daily supervised brushing. In addition to free dental treatments, the scheme gives parents and adult carers dietary advice to help them prevent tooth decay.

MacPherson chooses her words very carefully. She does not discount the benefits of water fluoridation, even as her initiative threatens to replace it as public dental health default. “I watched a previous generation of public health officials get nowhere with water fluoridation,” she says. A Scottish government consultation paper published in 2002, which floated the option of adding fluoride to all Scottish water supplies, attracted more than 7,500 complaints from Scots. But at the same time, damning surveys of oral health among children in Scotland made clear something had to be done. “There was no appetite to take the fluoridation route, but we needed to do something. So we agreed with the chief dental officer to be pragmatic.”

According to the Scottish government, Childsmile is now saving the country almost £5m a year in treatment costs. The number of primary-one children with no obvious decay experience has risen from 54% in 2006 to 68% in 2014. “It’s a more holistic approach,” says MacPherson. “The universal part, the equivalent of water fluoridation if you like, is the nursery toothbrushing. Then for the children more at risk of caries, we offer additional support. We call it proportionate universalism – something for everyone, but proportionate to their needs.”

Water fluoridation is often justified in public policy terms because, it is argued, it addresses social inequalities and reaches those children with the worst dental caries. In the UK, for example, children who are eligible for free school meals are more likely than others to report problems with their oral health.

But dentists agree that measures that reduce sugar consumption would be another way to help the children most at risk of tooth decay. Around one in eight children admit to drinking sugary drinks at least four times a day, but tooth enamel begins to dissolve when acid levels in the mouth dip below 5.5 on the pH scale. Colas have a pH of around 2.5.

The British Dental Association has described tax on sugary food and drink – such as the one just announced by the UK government – as an “entirely appropriate” way to improve health and reduce tooth decay among children, as well as obesity.

According to MacPherson, Childsmile aims to tackle these bigger issues, enabling children to make healthier choices for themselves, which won’t just impact oral health but wider health, too.

“No one disputes that water fluoridation would be effective to some extent, but it’s no silver bullet. On its own, it doesn’t tackle the underlying causes of caries,” says MacPherson, who now receives regular visits from curious public health officials from around the world. “It was time to move on.”

So what should our cities do? Follow Newcastle’s long history of fluoridation, or Hull’s reluctance to take on the doubters? Both sides, it would seem, lack the killer evidence to substantiate their claims.

Or should they take notice of Glasgow’s pragmatic compromise, a city where infant teeth-brushing and dietary initiatives are already paying measurable dividends? As any parent will tell you, you have to choose your battles. For the sake of our health – dental or otherwise – maybe our cities should do the same.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

• This article was amended on 15 April 2016 to clarify that the author’s requests to meet councillors or officials to discuss the consultation into fluoridation were sent to Hull city council’s press office, and to remove a statement that the fluoridation plans would cost £100,000 a year. An earlier version also said the council had announced it would be postponing consultation on fluoridation for at least 12 months. The council has commissioned a feasibility study from Yorkshire Water after which it will decide how and whether to proceed. No funds have been allocated for capital costs or consultation in this financial year, but Colin Inglis has made clear that this does not in any way imply a lessening of the council’s commitment to examining and moving forward with a fluoridation scheme.