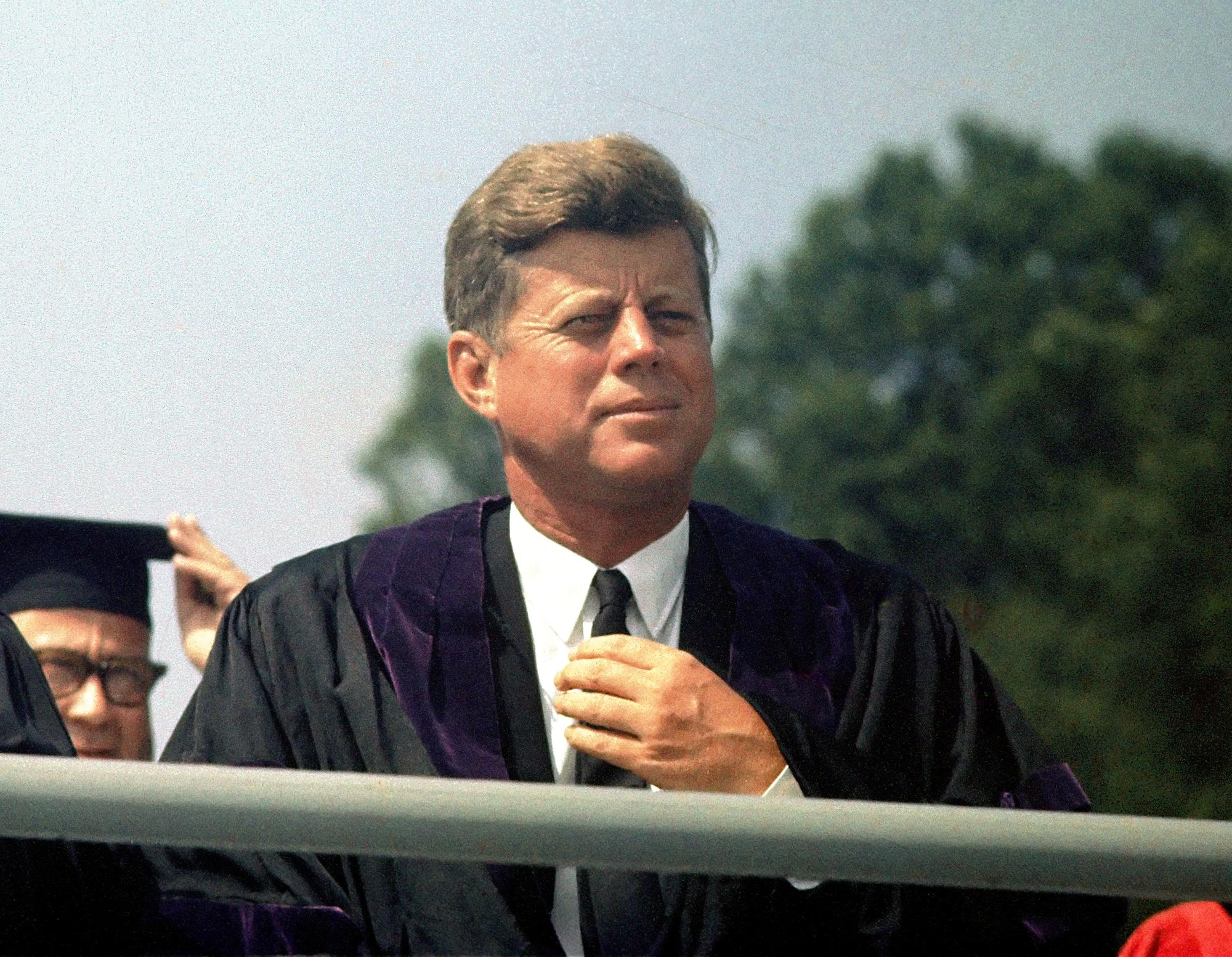

The JFK assassination files lead back to Seattle

Not unexpectedly, the latest release of government records collected from the investigation into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy did little to silence conspiracy theories, according to news reports. That includes a Seattle surgeon’s claim, which is reflected in the newly released records, that one of the doctors who operated on Kennedy confided he misled the Warren Commission about one of the president’s wounds.

In a nutshell, former University of Washington physician and professor Dr. Donald Miller Jr. says that the late Dr. Malcom Perry, the Dallas surgeon who tried to save Kennedy’s life on the Parkland Hospital operating table Nov. 22, 1963, questioned whether Lee Harvey Oswald fired all the bullets that struck Kennedy’s motorcade.

Miller, who later worked and taught with Perry at the University of Washington School of Medicine in the 1970s, says Perry told him there were entry wounds from both behind and in front of Kennedy, contradicting what he told the commission under oath. Perry confided similar details to an Alaska doctor as well.

“He took that to his grave,” Miller, a UW professor emeritus, says today. He claims that Perry, during a private conversation the two had in the late 1970s, said he’d been pressured to change his story and agree with the government’s theory that all entry wounds came from behind the motorcade. Perry had moved to Seattle in 1974 with Dr. Tom Shires, Parkland Hospital’s Chief of Surgery, who became Chairman of Surgery at the UW. Shires brought Perry and several other Parkland surgeons to the UW, including Dr Jim Carrico, the first doctor to examine Kennedy in the ER.

Records of Perry’s testimony and public comments, and Miller’s recollections of the private talk they had, are contained in the more than 20,000 JFK-assassination documents released by the National Archives over the past few weeks, including a fresh batch released Friday. Though some of the documents had already been released over the years, they were heavily redacted; the newest releases are, by comparison, lightly censored.

For the most part, the documents and an additional 52,387 searchable emails from the government’s Assassination Records Review Board recently posted on muckrock.com add to the widely accepted yet endlessly debated finding that Oswald acted alone.

But more than a half-century later, Miller says he, like Perry, doubts that’s true. He says Perry told him that a bullet wound in Kennedy’s neck was an entrance wound, despite having told the Warren Commission it was an exit wound.

If it was an entrance wound, that bullet would have been fired from the front of the president’s motorcade as it passed the now-infamous grassy knoll in Dealey Plaza.

Oswald, of course, was found to have fired at the motorcade from a rear position, the sixth floor window in the nearby Texas School Book Depository. Perry, who died in 2009, suspected there was more than one shooter, the Seattle doctor says.

“He told me in confidence,” says Miller, “and I waited until years after he died to tell anyone else.”

It was likely easier for Perry to go along with the mainstream theory, he says. But he was hardly alone in thinking there was a second shooter. The public was divided and even the government split on the question of who killed JFK: The Warren Commission found no evidence of another gunman, while the U.S. House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1979 concluded the shooting was a conspiracy and “probably” involved a second gunman.

Critics questioned both conclusions, claiming the commission and Congress were swayed as much by politics as by facts. True-crime books came to opposite conclusions, and critics raised questions about possible government destruction or manipulation of records and photographic evidence.

Elmer Moore, a Secret Service agent who worked with the commission and was later transferred to the service’s Seattle office, admitted he was ordered to pressure Perry to refute the two-gunman theory, according to a University of Washington graduate student who interviewed Moore and eventually testified at government hearings.

Perry had long been at the center of the controversy, and may have unintentionally started it. He performed a tracheotomy on Kennedy and also attended Texas Gov. John Connally who was wounded by a wildly ricocheting bullet that was said to have passed through Kennedy. Two days later, Perry also tended Lee Harvey Oswald, who bled to death after being shot by Jack Ruby in the Dallas Police Department basement.

At a press conference following Kennedy’s death, Perry said he used an existing wound on the president’s throat to perform the tracheotomy, since it was the precise location for access to the breathing tube. News reports stated that Perry indicated the site was a frontal entrance wound, which in addition to an entry wound in Kennedy’s back and the fatal rear head-and-brain shot, suggested there were two shooters firing at least three bullets from front and rear angles.

“The wound appeared to be an entrance wound in the front of the throat,” Perry told the media. For that to happen, “The bullet would be coming at him [from the front],” he said.

The Warren Commission concluded Oswald, alone, fired three shots, all from the rear, with one of them missing the motorcade and landing nearby.

Perry, appearing at his first major press conference and tasked with making sense of what would become perhaps history’s most disputed assassination, later admitted he was rattled, calling the press event “bedlam,” and saying he didn’t know for sure if the throat wound was entry or exit.

He told friends he was pressured by government officials and the Secret Service to back away from the entry wound claim, since the official autopsy showed it to be an exit wound.

And that may have indeed been what happened. All Perry had done was express some doubts. But that wasn’t the message deep government wanted to hear.

University of Washington graduate student James Gochenaur, who spoke with Secret Service agent Moore in a 1970 interview, subsequently told the House assassination committee and the Church Committee, chaired by Sen. Frank Church, D-Idaho, that Moore admitted to putting the squeeze on Perry after the press conference.

Gochenaur said Moore, who died in 2001, called Kennedy a “traitor” for being soft on the Russians, and suggested that it was too bad people had to die but maybe it was a good thing for the U.S., and that the Secret Service had quickly made up its mind that Oswald acted alone.

“I did everything I was told, we all did everything we were told, or we’d get our heads cut off,” Gochenaur quoted Moore. He was remorseful for badgering Perry but had no choice, Gochenaur recalled him saying.

Some of the newly posted e-mails collected by the assassination review board expand on Moore’s role in badgering Perry and even getting him to flip and challenge others who argued there were two shooters. (The review board was an independent agency that examined assassination-related records for public release from 1994 until 1998, then transferred its records to the National Archives.)

In 1964, Perry appeared to confirm his belief of a sole shooter during testimony before the Warren Commission. A transcript shows he initially said he did not know whether the wound was exit or entry. But under the intense questioning of commission counsel (and later Republican senator) Arlen Specter, he came around.

“Based on the appearance of the neck wound alone,” Specter asked, “could it have been either an entrance or an exit wound?” Either, Perry responded.

Specter laid out an elaborate shooting scenario that included the likelihood that a 6.5 mm. copper-jacketed bullet fired from a rifle up to 250 feet away and having a muzzle velocity of approximately 2,000 feet per second could have passed through the president’s back and exited from the neck.

Assuming those facts to be true, Specter asked, would the neck hole be consistent with an exit wound?

“Certainly would be consistent with an exit wound,” Perry said, based on that scenario.

“A full jacketed bullet without deformation passing through skin would leave a similar wound for an exit and entrance wound,” he added, “and with the facts which you have made available and with these assumptions, I believe that it was an exit wound.”

Critics questioned how, based on some forensic findings, a bullet fired from the sixth floor to the ground level entered Kennedy’s back and then traveled upward to exit through the throat. Perry apparently wondered, too. Three years after the surgeon’s death, Miller claimed in a little-noticed 2012 blog post that Perry doubted the scenario. The author of three books and a frequent writer on current medical and political topics, Miller wrote:

“Fifteen years [after the shooting], Dr. Perry told me in a surgeon-to-surgeon private conversation that the bullet wound in Kennedy’s neck was, without question, a wound of entrance, irrespective of what he had told the Warren Commission.

“This seasoned attending trauma surgeon had seen a lot of gunshot wounds at Parkland Hospital and knew what he was talking about. Dr. Perry also told this ‘off the record’ truth to another physician, Dr. Robert Artwohl, in 1986.”

Artwhol, an Anchorage surgeon who wrote an online post about their conversation, stated that Perry told him that “[o]ne of the biggest regrets in his life was having to make the incision for the emergency tracheotomy through the bullet wound… Speaking with Dr. Perry that night, one physician to another, Dr. Perry stated he firmly believed the wound to be an entrance wound.”

But, Miller said in his blog that after agent Moore and others pressured Perry to alter his story, “This otherwise bold surgeon backed down and obligingly changed his testimony to suit the politically ordered truth that Oswald did it.”

That’s pretty much how history sees it today, as well. Of course, that’s debatable.