Reality or studio shoot? Why moon landing conspiracy theories still exist

Bill Kaysing was a former US Navy officer who worked as a technical writer for one of the rocket manufacturers for NASA’s Apollo moon missions. He claimed that he had inside knowledge of a government conspiracy to fake the moon landings, and many conspiracy theories about the Apollo moon landings which persist to this day can be traced back to his 1976 book, We Never Went to the Moon: America’s Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle.

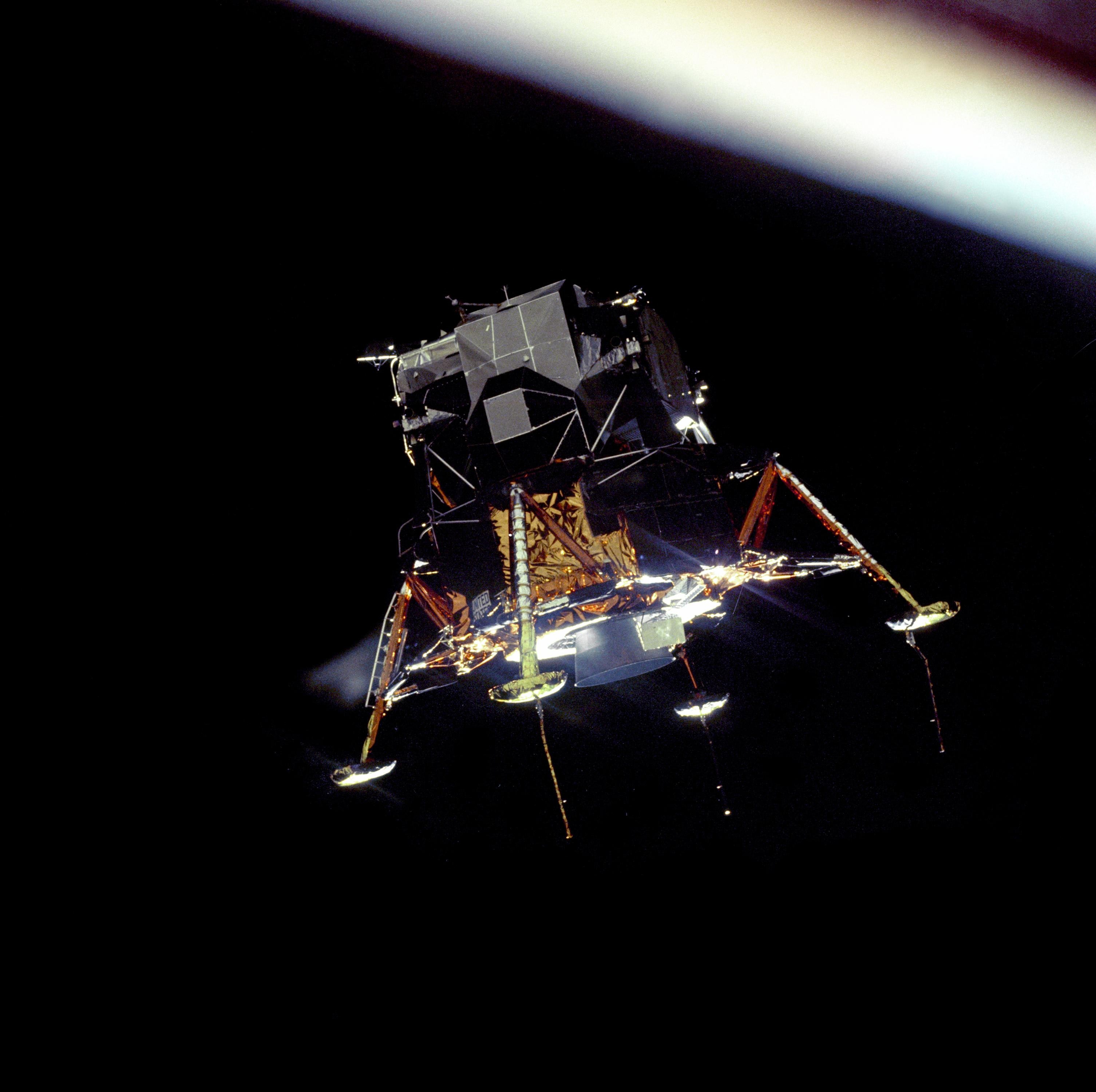

The basic template of the conspiracy theory is that NASA couldn’t manage to safely land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s as President John F Kennedy had promised, so it only sent astronauts into Earth orbit. Conspiracy theorists then argue that NASA staged the moon landings in a film studio and that there are tell-tale signs on the footage and the photos that give the game away. They claim that NASA has covered up the elaborate hoax ever since.

Moon landing sceptics point to supposed clues such as photos that appear to show the astronauts in front of cross hairs that were etched on the camera glass, or a mysterious letter C visible on a moon rock. These and many other seeming anomalies have been debunked, but moon landing conspiracy theories have persisted in the popular imagination.

In the US, opinion polls indicate that between 5-10% of Americans distrust the official version of events. In the UK, a YouGov poll in 2012 found that 12% of Britons believed in the conspiracy theory. A recent survey found that 20% of Italians believe that the moon landings were a hoax, while a 2018 poll in Russia put the figure there as high as 57%, unsurprising given the popularity of anti-Western conspiracy theories there.

To the moon and beyond is a new podcast series from The Conversation marking the 50th anniversary of the moon landings. Listen and subscribe here.

Ready to disbelieve

That Kaysing’s conspiracy theory took hold in mid-1970s America is in large part due to a wider crisis of trust in the country at the time. In 1971, citizens read the leaked Pentagon Papers, showing that the Johnson administration had been systematically lying about the Vietnam War. They tuned in nightly to the hearings about the Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up.

A series of congressional reports detailed CIA malfeasance both at home and abroad, and in 1976, the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded – in contrast to the Warren Commission more than a decade earlier – that there was a high probability that there had been a conspiracy to kill Kennedy. These revelations had helped fuel a wider shift in conspiracy thinking since the late 1960s, from a belief in external enemies, such as Communists, to the suspicion that the American state was itself conspiring against its citizens.

Moon landing conspiracy theories have proved particularly sticky ever since. To understand their popularity we need to consider their cultural context, as much as the psychological dispositions of believers.

As with the Kennedy assassination, they formed a new kind of conspiracy theorising.

These theories reinterpret the publicly available evidence, finding inconsistencies in the official record, rather than uncovering suppressed information. Visual evidence is crucial: for all their scepticism, their starting point is that seeing is believing. In the realm of photo evidence, the assumption is that everyone can be a detective. In the conspiracy theory communities that emerged at the tail-end of the 1960s, the self-taught buff became central.

Constructed reality

The moon landing conspiracy theories also brought to the mainstream the notion that significant events are not what they seem: they have been staged, part of an official disinformation campaign. The idea that tragic events are created by “crisis actors” employed by the government has become the default explanation for many events today, from 9/11 to mass shootings. This type of conspiracy theory is particularly harmful – for example, parents of children killed in the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting have been relentlessly hounded by internet trolls claiming they are merely paid stooges.

However, the story that the lunar landings were staged also resonates with the more plausible notion that the space race itself was as much a Cold War spectacle as a triumph of the human spirit.

![]()

The 1978 Hollywood film Capricorn One did much to popularise moon landing conspiracy theories. Based on Kaysing’s book, it imagined that a Mars landing was faked in a film studio, tapping into conspiracy rumours that the moon landings themselves had been directed by Stanley Kubrick. This suggestive myth is based in part on the idea that special effects had become much more sophisticated with Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001 A Space Odyssey, although still far from the capabilities that the conspiracy theories suppose.

Even if they are far-fetched in factual terms, moon landing conspiracy theories nevertheless call up the more plausible possibility that in our media-saturated age reality itself is constructed, if not actually faked.

Peter Knight, Professor of American Studies, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

Business Standard has always strived hard to provide up-to-date information and commentary on developments that are of interest to you and have wider political and economic implications for the country and the world. Your encouragement and constant feedback on how to improve our offering have only made our resolve and commitment to these ideals stronger. Even during these difficult times arising out of Covid-19, we continue to remain committed to keeping you informed and updated with credible news, authoritative views and incisive commentary on topical issues of relevance.

We, however, have a request.

As we battle the economic impact of the pandemic, we need your support even more, so that we can continue to offer you more quality content. Our subscription model has seen an encouraging response from many of you, who have subscribed to our online content. More subscription to our online content can only help us achieve the goals of offering you even better and more relevant content. We believe in free, fair and credible journalism. Your support through more subscriptions can help us practise the journalism to which we are committed.

Support quality journalism and subscribe to Business Standard.

Digital Editor