Apollo 11: the Moon landing conspiracy debunked

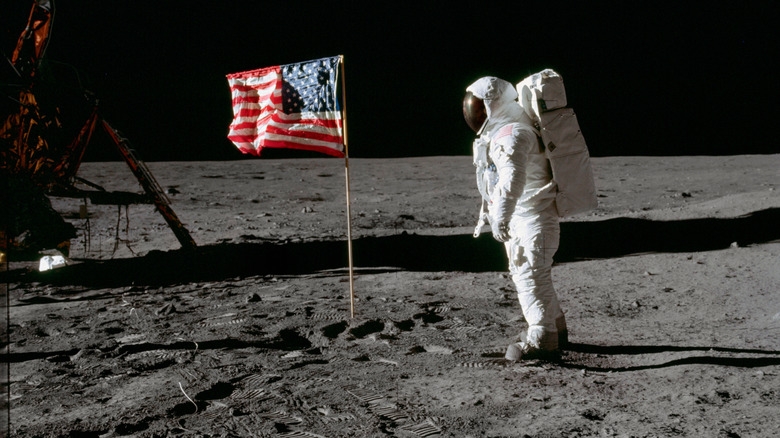

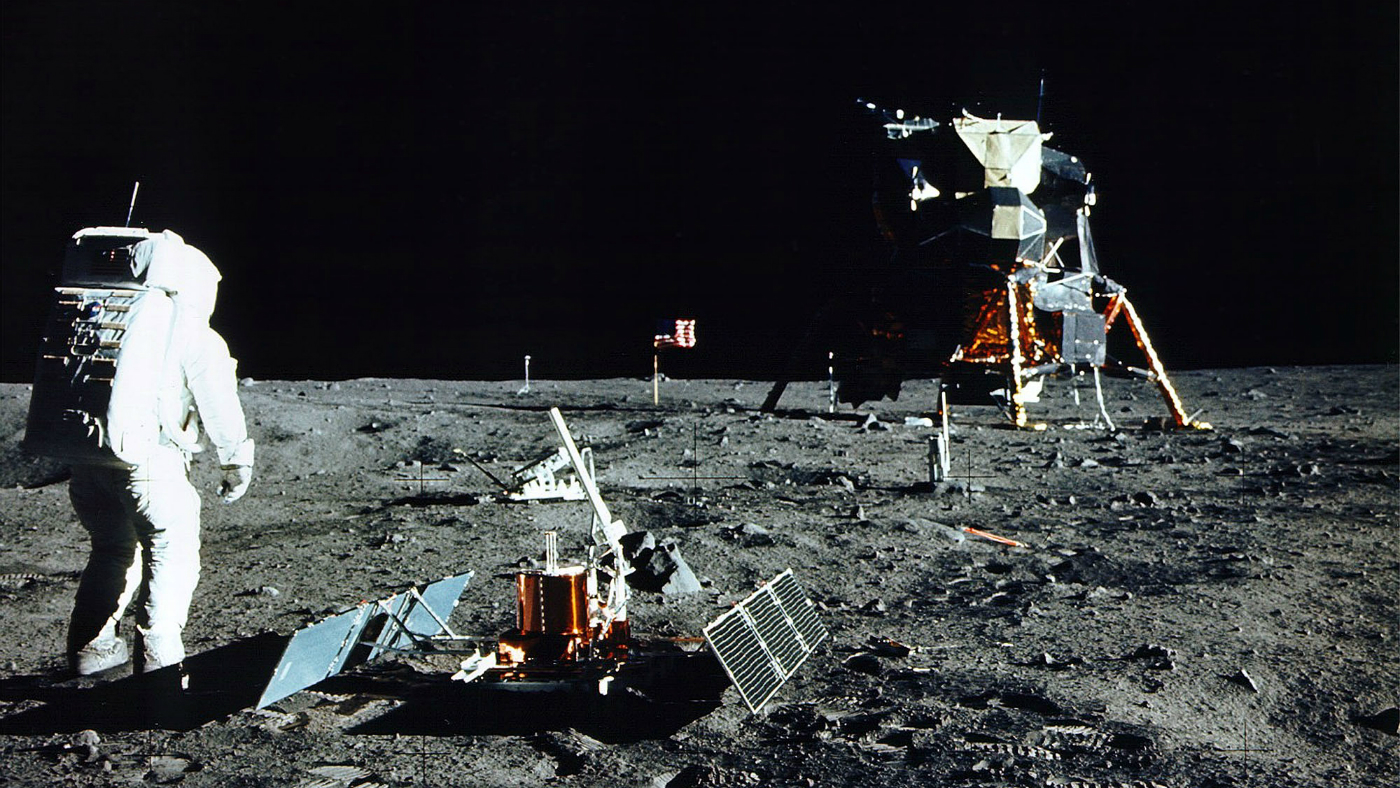

On 20 July 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission, with the help of around 400,000 Nasa employees and contractors.

Or did they? Not everyone is convinced.

The now-famous hoax Moon-landing conspiracy theory started with “one small step” by former US Navy officer Bill Kaysing…

What is the theory?

Kaysing believes the whole mission was created in a TV studio.

The basic premise is that since President John F. Kennedy could not accomplish his promise of landing a man on the Moon by the end of the 1960s, Nasa sent astronauts into Earth orbit instead, explains Peter Knight, a professor of American Studies at the University of Manchester.

Kaysing, who contributed to the US space programme between 1956 and 1963, said he had “a hunch, an intuition” that the US lacked the technical powers to make it to the Moon and back.

In 1976, Kaysing self-published We Never Went to the Moon: America’s Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle, a pamphlet that used grainy photocopies as “evidence” and fabricated theories.

The proof of the landing included 382kg of Moon rock, collected from six missions; endorsements from Russia, Japan and China; and images the Nasa Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter took showing tracks made by the astronauts.

Kaysing brought up points such as the lack of stars as well as a blast crater in the pictures. He also notes the way the shadows fall, The Guardian reports.

On an episode of ITV’s This Morning last year, one believer in the conspiracy theory, Martin Kenny, argued that no one could have walked on the Moon.

“In the past, you saw the Moon landings and there was no way to check any of it,” he said. “Now, in the age of technology, a lot of young people are now investigating for themselves.”

“It’s well documented that Nasa was often badly managed and had poor quality control,” Kaysing told Wired in 1994. “But as of ’69, we could suddenly perform manned flight upon manned flight? With complete success? It’s just against all statistical odds.”

Although correct that the US space programme was non-existent at the time of the Soviet’s launch of Sputnik 1 in October 1957, Kaysing’s reports seem like a stretch.

Why is it not true?

For the landing to have been created in a television set, 2019-era special effects would have been needed in 1969.

“Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is a decent indication of what Hollywood special effects could do at the time – and it’s extremely shonky. It genuinely was simpler to film on location,” says the Guardian.

And the 600 million TV viewers who watched the landing never reported anything amiss, notes the paper.

Many of the conspiracy theories have been debunked, including the lack of stars, which is explained by the Moon being brightly lit by the Sun, making stars look black, says Royal Museums Greenwich, which houses the Royal Observatory. The permanence of footprints, the BBC points out, can be explained by the lack of wind, rain and other weather activities typical on Earth.

Others point out that the secret would have had to be kept under wraps, with no leaks, for five decades.

Why do they still persist?

Belief in the conspiracy theories has grown over the years, culminating today with one in six Brits believing the Moon landings were probably or definitely staged, according to a YouGov poll.

The fact that no further missions to the Moon were carried out by Americans after 1972 has added fuel to the fire.

First-hand witnesses are passing away, notes Roger Launius, a former chief historian of Nasa, which makes it easier for people to deny it even took place.

“The reality is, the internet has made it possible for people to say whatever the hell they like to a broader number of people than ever before,” Launius tells the Guardian. “And the truth is, Americans love conspiracy theories. Every time something big happens, somebody has a counter-explanation.”