Doubters, difficulty and distance – Apollo 11’s LRR experiment

<!–

To hear Moon landing conspiracy theorists tell it, the U.S. never sent men to the Moon during the Apollo Program of the 60s and 70s. A recent SpaceFlight Insider interview about a remote facility suggests otherwise.

–>

Jason Rhian

July 18th, 2019

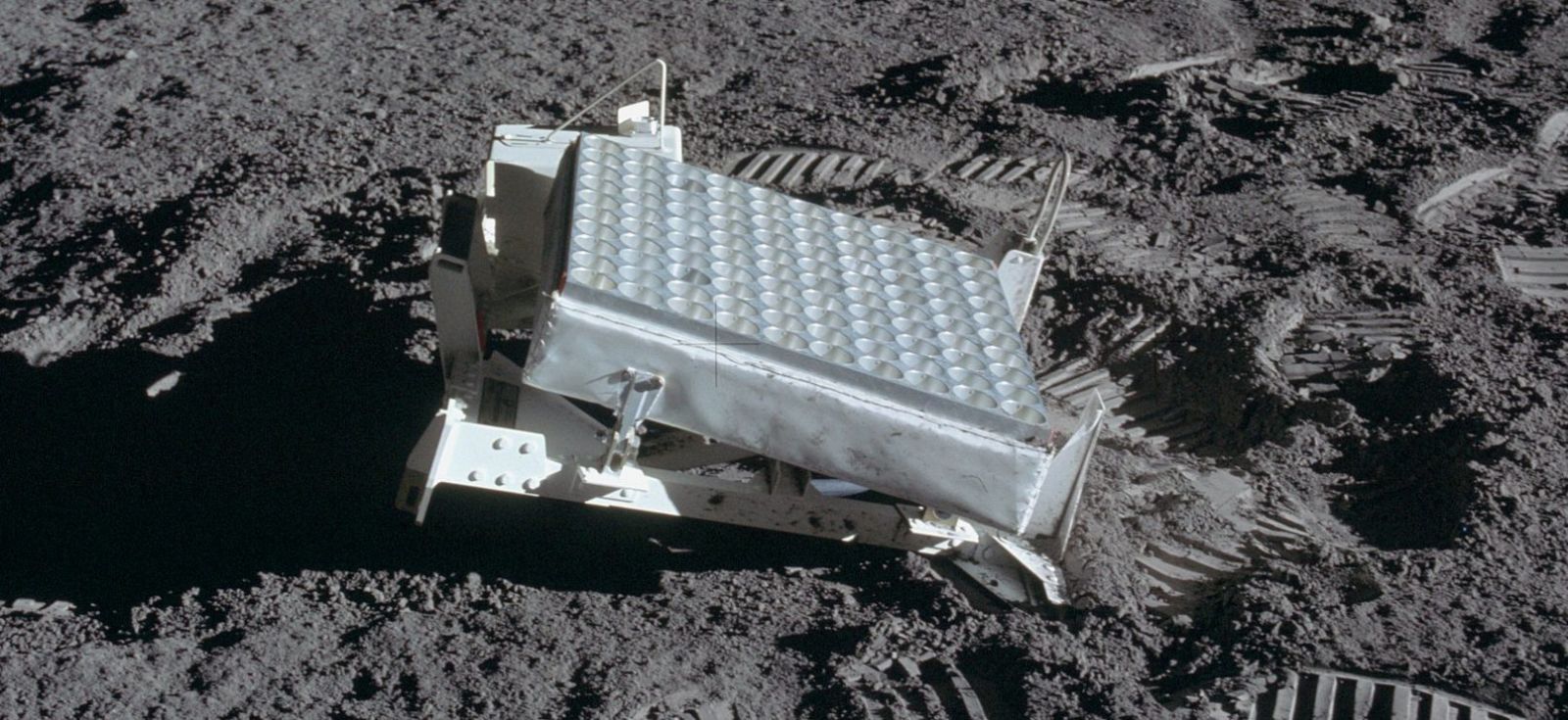

A Laser Ranging Retroreflector on the Moon. These experiments were used for decades after astronauts placed them there during the Apollo Program. Photo Credit: NASA

To hear Moon landing conspiracy theorists tell it, the U.S. never sent men to the Moon during the Apollo Program of the 60s and 70s. A recent SpaceFlight Insider interview about a remote facility suggests otherwise.

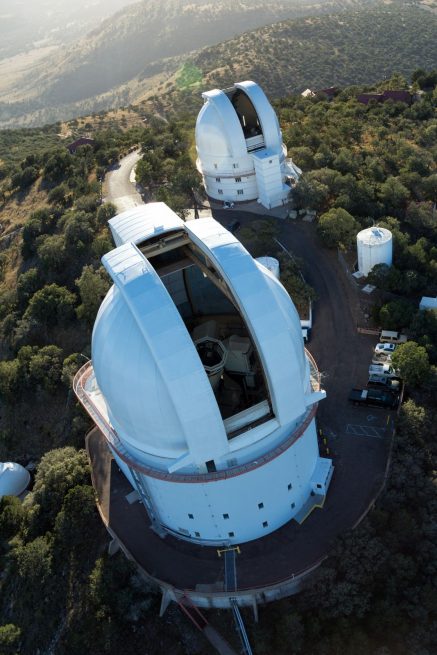

McDonald Observatory is located in Davis County, Texas, and has used Laser Ranging Retroreflector experiments left behind by the crews of Apollo 11, 14, and 15 for some time. These devices were used to help gage the distance between the Earth and the Moon.

Just a month after Neil Armstrong took the first “small step” on the Moon, McDonald Observatory bounced a laser beam off a reflector left on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission. The experiment measured the Earth-Moon distance with an accuracy of a few inches.

Apollo 11’s Lunar Module Pilot, Buzz Aldrin, placed the device (which is comprised of a series of corner-cube reflectors), down on the surface of the Sea of Tranquility in July of 1969. It was used for decades to further humanity’s understanding of how Selene (the Greek goddess of the Moon) orbits Earth.

The LRRs placed on the Moon during Apollos 11, 14 and 15 have been used by the McDonald Observatory to measure the distance between the Earth and the Moon for decades. Photo Credit: McDonald Observatory

The mirrors on the LRR are designed to always reflect an incoming light beam back in the direction that it came from. A similar device was also included on the Soviet Union’s Lunakhod 2 spacecraft. These reflectors can be illuminated by laser beams aimed through large telescopes on Earth. The reflected laser beams provide a measurement of the round-trip distance that they take on their flight between Earth and the Moon.

Many of these measurements have been made by the McDonald Observatory from 1969 to 1985. The Observatory’s 107-inch telescope made many of these measurements. After 1985, the observations were made using a dedicated 30-inch telescope.

Laser beams are the weapon of choice when it comes to accurately measuring the distance between our home and the first stop on a journey beyond low-Earth orbit.

To be sure, the signal is weak. Observations take several hours despite the tight, coherent nature of lasers – the beams were about 4 miles (7 kilometers) in diameter when they reached the Moon – and 12 miles (20 kilometers) in diameter when they returned home.

The average distance between the Earth and the Moon is estimated at being about 239,228 miles( 385,000 kilometers). What’s not commonly known is that the Moon is slowly pulling away from Earth (to the tune of almost an inch-and-a-half or four centimeters per year). Perhaps most interesting of all is that the LRR has even been used to test Einstein’s theory of relativity.

That’s some pretty heavy street cred. Those who work at the McDonald Observatory don’t shout this from the rooftops. Their approach to the data they collected from Apollo 11 is calm, professional and understated. Such became clear when speaking with Jerry Wiant who works at the observatory as a research engineer.

“If there’s anything I can do to improve the quantity or quality of the data that the scientists gain better, that’s my job,” Wiant told SpaceFlight Insider. “I talk to these detractors, I don’t have any reason not to, and I try to answer their questions the best I can.”

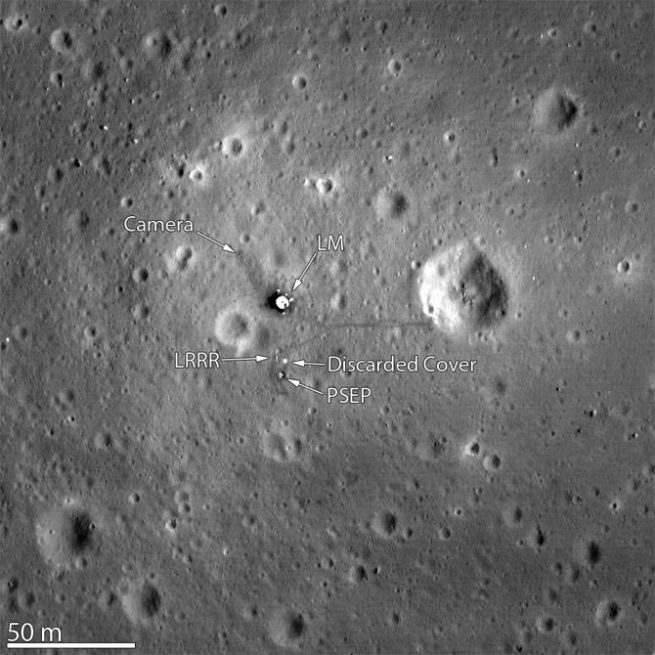

When asked about theorists’ assertions, he pointed to a more recent mission to Луна (Russian for Moon), one which provided even more evidence that men set foot on another world – the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter or “LRO.”

“There are a lot of people who say we didn’t go there [the Moon]. I’ve been here for a number of years and I take a different view from those who don’t think we landed on the Moon. All someone has to do is look up the published photos from the LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) mission. A viewer can look at various sites and in one of them you can see where the astronaut had shuffled his feet as he walked from a rover over to the edge of a crater. Due to the Moon’s one-sixth gravity, they couldn’t step like you or I would, they ‘shuffled.’ Those photos really knock a hole in a lot of people’s argument.”

The Apollo 11 landing site, as well as the LRRR experiment can be seen in this image captured by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Image Credit: NASA Goddard/Arizona State University

LRO was launched in 2009 atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V 401 rocket. The $583 million mission ($504 million for the LRO probe, $79 million for the LCROSS satellite that accompanied it) was launched as a precursor for future robotic and crewed missions. Detractors have not been convinced to reconsider their views, claiming the images were faked.

“I had a number of phone conversations with a gentleman who apparently represented a group of people who don’t think we went there,” Wiant told SpaceFlight Insider. “I believe if more of these detractors reached out to us, or even visited us, they would walk away with the understanding that there is something there we’re using to do research and we might even be able to convince them that we really did go.”

An estimated 5 percent of the population still believe the U.S. didn’t send the trio of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins on their historic journey in July of 1969 (much less carried out six similar flights, five of which were successful). Some of these people have either formed or are members of groups. One of these groups has been in contact with Wiant.

“I don’t want to use his real name, so I’ll give him the ‘handle’ of ‘Gentleman X.’ We had a number of really pleasant phone calls. He would ask a question and I would do my best to answer from a repair person’s point-of-view,” Wiant said, expanding on the conversations that they had noting that “Gentleman X” had gone on to ask when would be the best time for members of his group to visit.

Wiant provided “Gentleman X” with what he knew to be fact, what he had been told and allowed him to draw his own conclusions.

After detailing the difficulties involved and in an interesting twist of irony, Wiant told “Gentleman X” that members of his community were unlikely to believe him, that the only way for people to know for sure would be to visit the sites where the Laser Ranging Retroreflectors were deployed. So, in the same way that Apollo astronauts had to face critics who refused to accept their accomplishments, detractors who now had reviewed the data for themselves and understood what they were told was accurate also wouldn’t be believed.

The Observatory’s 107-inch telescope was used for many of the measurements. After 1985, the observations were made using a dedicated 30-inch telescope. Photo Credit: McDonald Observatory

In a display of total honesty, Wiant mentioned that with all the modern technology available to anyone, detractors could claim that imagery and certain data had been photo shopped or faked. However, given the volume of technicians, engineers, scientists and even the U.S.’ Cold War rival, Russia, who have reviewed the data themselves and haven’t debunked the imagery, conspiracy theorists’ claims appear shaky at best.

Wiant downplayed his role with the observatory, describing himself as a repairman. In fact, he is an electronic design engineer, who keeps some of the equipment operating so that it can perform as advertised, but as he is not a scientist, he does not conduct the experiments that are carried out at the observatory.

It has been half a century since Aldrin placed the reflector experiment on the Moon, a long time for something to work in the near-vacuum and dust-laden environment of the Moon. For the past few years, the observatory has been unable to range on the Moon due to a damaged light detector. Sadly, the organizations involved with the experiment have been unable to provide the necessary funding to have the device repaired.

As are most things involving science and engineering, the devil is in the details and getting the data required isn’t always easy. Ranging the Moon is a tempermental business, one that is extremely dependent on weather conditions, wind, moisture in the atmosphere or even very thin cirrus clouds can impact gaining accurate measurements.

“It has taken us weeks to get the information we needed, because that’s the nature of the beast,” Wiant said. “This is reality, this is how sparse the data is. The only way for conspiracy theorists to know and ‘own’ the information is for you to pay the Russians to fly you to the Moon so that you can walk around, specifically at an Apollo landing site and see for yourself that it is there.”

Perhaps in a sad statement of the status of public perception and support, Wiant’s mentioning of who was capable of sending people to the Moon, the Russians (although they too lack the required support system and vehicles to achieve the feat), is a testament to the state Apollo’s legacy. A half a century after the footprints were placed into the dust, the United States is unable to send astronauts to low-Earth orbit and five percent of the population believe the event was staged.

July 20, 2019 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s landing on the surface of the Moon. Image Credit: NASA

Jason Rhian

Jason Rhian spent several years honing his skills with internships at NASA, the National Space Society and other organizations. He has provided content for outlets such as: Aviation Week & Space Technology, Space.com, The Mars Society and Universe Today.

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from SpaceFlight Insider can be found here ***