My Seventh Grade Science Teacher Showed Us a Moon Landing Hoax TV Special

When I was in seventh grade, circa 2003, my science teacher showed us a video making the case for the moon landing hoax theory. It was the Fox TV special Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? which aired in prime time (twice) in 2001. Fox even bragged about the show’s impact: The Deseret News reported in 2002 that “a 1999 poll found that 11 percent of the American public doubted the moon landing happened, and Fox officials said such skepticism increased to about 20 percent after their show, which was seen by about 15 million viewers.” According to one report, even a few people at the National Science Foundation thought the hoax was possible after watching the special.

As far as I know, my teacher was not a moon landing truther, and this was not an act of political indoctrination. In fact, she reacted with surprise and not a little bit of horror when several kids said, after watching the video, that they were no longer sure whether we went to the moon at all. I have no idea if any of these kids went on to become truthers of any sort, but I can say that the show planted a seed of doubt where none existed before.

Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? is, unfortunately, available for streaming on Netflix, where it is classified as a documentary (albeit with the tags “controversial” and “provocative”). In honor of the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, I watched it, again, so you don’t have to. With its relentless soundtrack of ominous musical cues, its hokey crosshair effects, and its sneering narration by Mitch Pileggi (Walter Skinner on The X-Files), the show is really quite earnest—like a History Channel–style mystery about the Roanoke Colony or the Bermuda Triangle. And almost 20 years after its debut, it feels more dangerous than ever.

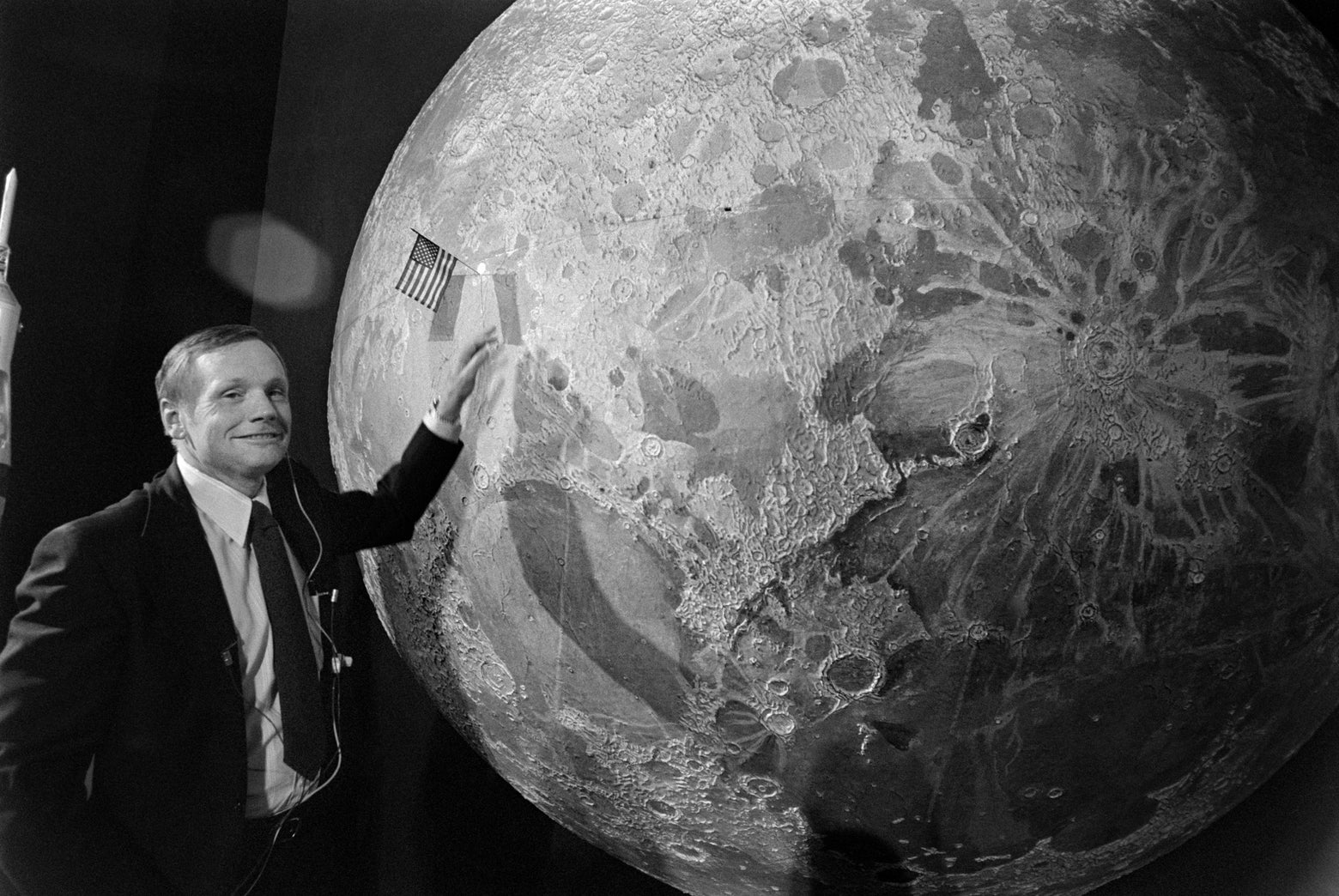

For 43 minutes (without commercial breaks), a series of “experts” lay out the supposedly damning evidence for a nefarious cover-up by NASA and the U.S. government: inconsistencies of light and shadow in moon photographs. The “waving” American flag. The apparently telltale similarity of the moon’s surface to the Nevada desert. The deaths of 10 astronauts. All these claims and more have been so strenuously and repeatedly debunked over the years that they are not worth elaborating here. But perhaps the saddest hoax point of all is the truthers’ conviction that the moon landing was technically impossible—that it didn’t happen simply because it couldn’t have.

What is most troubling about the program now, in 2019, is its inherent bothsidesism. The show opens with this disclaimer:

The following program deals with a controversial subject.

The theories expressed are not the only possible interpretation.

Viewers are invited to make a judgment based on all available information.

It claims to innocently present the “available information”—an alternate reality where the lies go all the way to the top. It gestures disingenuously toward its “controversial subject” with shrugs like “decide for yourself,” “you be the judge,” and “we may never know,” while plainly stacking the deck for a vast government conspiracy. The NASA flack given the unenviable task of rebutting the truthers’ claims is edited into insignificance. We are asked to believe that the talking heads—independent investigators and purported insiders and, notably, one cosmonaut—know what happened on Apollo 11 better than those who participated in the mission, that their opinions deserve the same weight as the facts.

Did We Land on the Moon? is a relic of a moment when conspiracy theories, if you didn’t believe them, seemed like harmless fun. This was the era of The X-Files and The Lone Gunmen (both Fox shows) and Conspiracy Theory, the madcap 1997 thriller in which the conspiracy theorist, played by Mel Gibson, is the hero. There’s some element of that today, too. Amanda Hess recently wrote in the New York Times:

The internet’s biggest stars are using irony and nonchalance to refurbish old conspiracies for new audiences, recycling them into new forms that help them persist in the cultural imagination. Along the way, these vloggers are unlocking a new, casual mode of experiencing paranoia. They are mutating our relationship to belief itself: It is less about having convictions than it is about having fun.

Maybe that’s what my science teacher was going for: a lighthearted distraction, something for us to laugh at, too self-evidently silly to be taken seriously. But when conspiracy theories drive people to attack a synagogue or a pizza parlor, or to torment the families of shooting victims, or to question the citizenship of a president, there’s nothing fun about paranoia. I hope none of my classmates think today that the moon landing was a hoax—but I wouldn’t be shocked if someone did.

Future Tense

is a partnership of

Slate,

New America, and

Arizona State University

that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.