50 Years After the Moon Landing: Why Conspiracy Theories Won’t Die

Controversy over “fake news” burst into view again this past weekend, on the anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission .

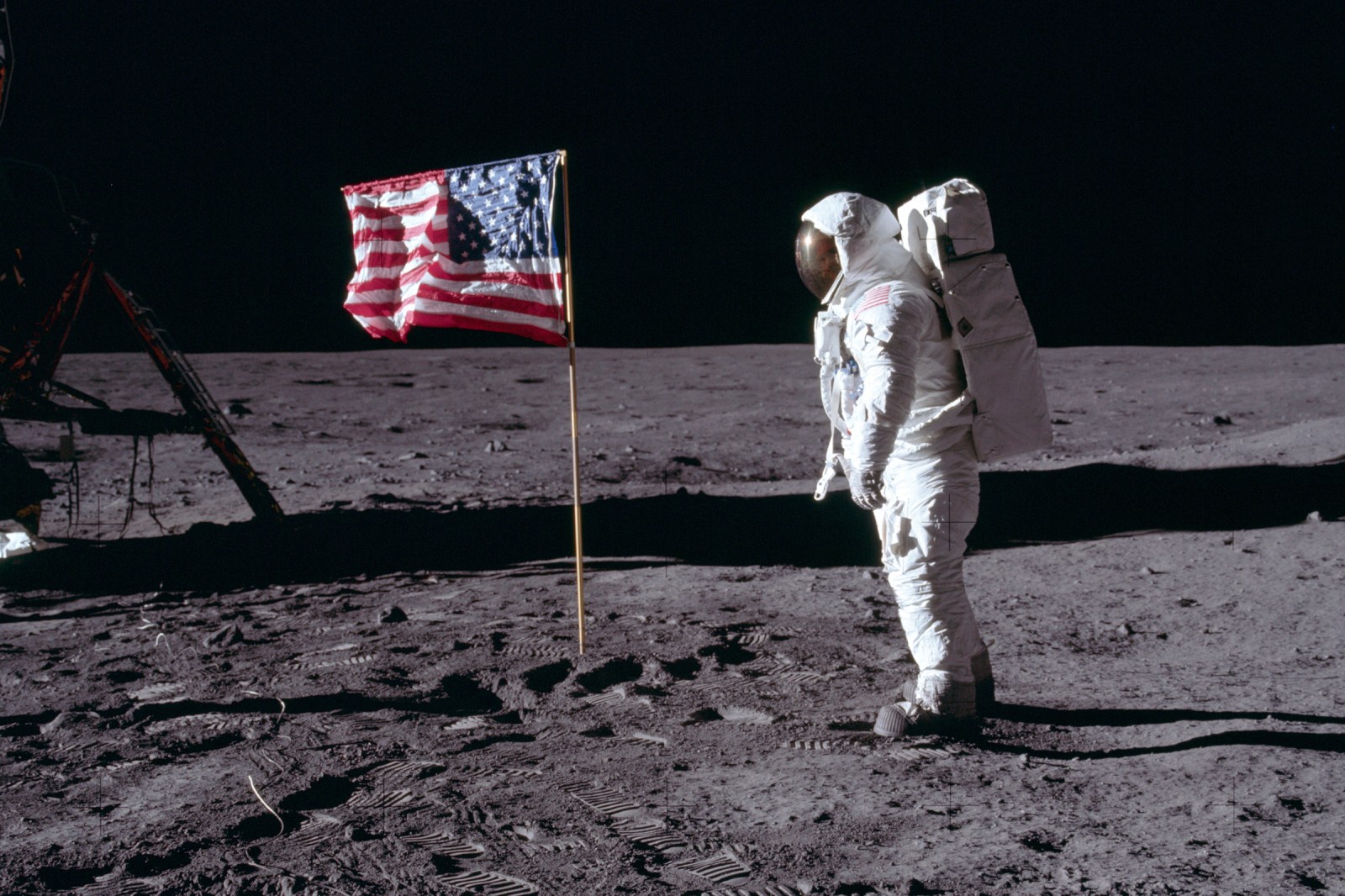

Saturday, July 20th marked 50 years since astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin beat the Soviets’ ill-fated unmanned Luna 15 to the lunar surface. The coming of this date was long a pop culture fixation.

Between Hollywood’s First Man (deftly casting emotionally absent Ryan Gosling as Armstrong) and an onslaught of retrospectives on Discovery, NatGeo, Science and Smithsonian channels, reliving Apollo has been one of the few feel-good media stories going.

As multiple news outlets complained this weekend, however, many Americans don’t share the love. The number of people who believe the moon landing didn’t happen seems to have risen in the last 20 years.

USA Today as an example ran a piece about Bart Sibrel, the 55 year-old Tennessean who got punched by Buzz Aldrin back in 2002 and still thinks the mission was a CIA movie production (a common theory is that Space Odyssey’s Stanley Kubrick directed). Like anti-vaxxers, moon deniers have become a fixation of the press in recent years, with NBA star Steph Curry among those attracting scorn.

Michael Smerconish on CNN also did a piece recently about Sibrel and others, bringing a psychology professor on to wonder aloud at the stupidity of flat-earthers (hello, Kyrie Irving!), O.J.-defenders, and Apollo deniers.

One of the points made? Research showing people who believe in conspiracies would be willing to participate in conspiracies themselves. In other words, bad people make bad news consumers.

It’s more complicated than that, but the moon landing fables are weak. Americans in general bring a high degree of literary skill to crafting conspiracy tales. Not in this case.

The thinnest tales involve massive numbers of would-be conspirators who successfully keep quiet and are only found out when a bored hobbyist declares reported reality scientifically impossible. They’ll then find the face of Jesus in a picture of a tree stump, or an alien satellite in a photo of space debris, or, in this case, a reflection of a stage grip in an astronaut’s visor.

The old “physical impossibility” saw is a nervous tic found in a lot of the trashiest American conspiracy tales. Only a controlled demolition could cause building 7 to free fall! Fertilizer couldn’t have felled the Murrah building in Oklahoma City! Look at the fatal head shot that killed Kennedy – it’s back, and to the left. The wrong way!

There are real conspiracies that are found out by technical observers catching inconsistencies. The LIBOR scandal was uncovered in part because financial analysts saw the interest rate benchmark’s fluctuations didn’t match other measures of lender confidence, for instance.

But cases like that are usually followed up by investigations that find witness evidence and explain the problem (in the case of LIBOR, it turned out banks were not measuring real economic activity when they submitted rate numbers). If your best evidence for decades is a shadow and a spot on a visor, you might want to think about moving on.

Still, the number of people who don’t buy the moon story is quite small, around 5% of the population. Compare that to the 70-plus percent who believe in angels, the 45% who believe in ghosts, or the 35% who believe aliens have landed on earth, and it’s clear you’re dealing with a tiny minority.

Stories about the goofy beliefs of the body politic were once mere asides in news coverage. In the Trump era, people who indulge in oddball belief systems are considered dangerous villains, the root of their thinking searched for in the way scientists would look for causes of cancer. Accordingly, the number of chin–stroking media examinations of the “fake news” phenomenon has soared, as if it were some great cultural mystery.

It isn’t. As I found out over a decade ago when I wrote a book about the subject, titled The Great Derangement, the flowering of conspiracy theories has an obvious correlation, to a collapse of trust in institutions like the news media and the presidency.

It’s simple math. You can only ask the public to swallow so many fictions before they start to invent their own. The moon story is a great illustration.

A blot on the Apollo narrative involved the moment when Armstrong and Aldrin, standing triumphant on the lunar soil, had to endure a long, rehearsed phone call from sweat-drenched corruption machine Richard Nixon. NASA was lucky to escape with this little: Nixon wanted to have “The Star-Spangled Banner” play after the landing. Still, it was an unpleasant reminder of how historical fact and politics can become intertwined.

A few years after Apollo 11, Nixon was driven from the White House in a scandal that fractured the American psyche. From that point forward, Americans would never again be shocked news by that their presidents were liars or worse.

The post-Nixon presidential progression went from a Bible-quoting Baptist who was considered honest, but too depressing (Carter), to a former corporate pitchman whose spin was at least cheery and professionally executed (Reagan), to Bill Clinton, whose idea of truth was the legally defensible statement, i.e. “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.”

When George W. Bush told the country 9/11 happened because, “They hate our freedoms,” he was not ridiculed by the national press, which co-signed his insane over-simplification of the terrorist phenomenon.

This helped set the the intellectual stage for the Iraq invasion, which involved a succession of ludicrous official deceptions, from the notion that Saddam Hussein was building a nuclear bomb to the idea that Iraq and al-Qaeda were in cahoots.

Smerconish’s CNN was a big player in that fiasco, not that the network ever admitted it (watch Wolf Blitzer squirming through an interrogation by Jon Stewart on this topic for a reminder). Audiences note these things.

Pile up enough official lies and media blunders and people start wondering: Did four out of five dentists really recommend Trident? How often do magazine editors alter cover images like they did with O.J’s face? Are press outlets spiking more than civilian casualty numbers, church sex scandals, and Jeffrey Epstein features?

From there they go to larger historical questions: was America really fired upon in the Gulf of Tonkin? Was there really a missile gap? What other mass-surveillance programs is the NSA hiding? And so on.

Travel around America and you’ll find people believe in a lot of weird stuff. You’ve got Facebook groups planning assaults on Area 51, cults that believe shape-shifting reptiles from outer space have infiltrated human government, even a Creation Museum that shows an Allosaurus skeleton as proof of the Biblical Flood.

These pockets of weirdness were once considered harmless, even a charmingly eccentric feature of American life. A major religion or two in this country grew out of groups of nuts practicing freedom of assembly.

Now the almost unanimous assessment of our intellectual elite is that loony strains must be stamped out, by policing of Internet sites if necessary. The thinking is, if it’s Sasquatch sites today, it’ll be eugenics and QAnon tomorrow.

Maybe so, but until we face the reasons people lost faith in official narratives in the first place, conspiracy theories will probably keep proliferating. It’s not that people don’t want to believe objective truth. It’s just getting harder to find where that is.

This background was a huge and underreported subtext to the Trump phenomenon. Media outlets continue to assign battalions of reporters to the task of documenting Trump’s deceptions, in the apparent belief this will impact his support.

But Trump’s voters know he lies, and mostly don’t care. They view his personal bleatings as less damaging than institutional deceptions on the other side.

Both Trump’s campaign and the run of Bernie Sanders in 2016 attracted voters who had tuned out mass media narratives, which are now viewed by significant numbers of people on both the left and the right as inherently corrupt and untrustworthy.