Combat anti-vax progress with education and national support

Measles outbreaks are no longer reserved to limited areas, but have become a nationwide problem. So what’s next?

Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, FAAP, professor of pediatrics and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston, Texas, addressed this in a session titled, “The Antivaccine Movement in Post-Measles America: What’s Next?” presented on October 25th at the 2019 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Annual Conference and Exhibition in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Measles, although not evenly dispersed, is now found across the nation, with more than 1200 cases reported across 31 states so far in 2019. Three-quarters of these cases are linked to unvaccinated individuals, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Hotez says measles isn’t the only problem facing children who are victims of the anti-vaccine movement.

“It’s not only measles,” Hotez says. “We had 600 kids die a year ago despite recommendations to vaccinate them. It’s also influenza.”

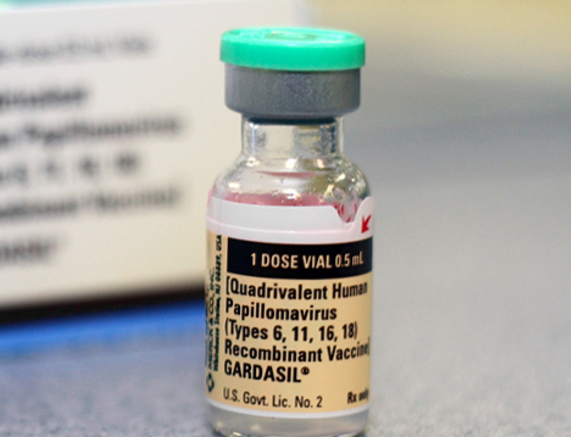

He called efforts to vaccinate against human papillomavirus (HPV) “useful,” but says the United States is far from the success seen in Australia, which expects to eliminate cervical cancer altogether by 2035, whereas in many US states only about 50% of teenaged girls receive the vaccine.

The blame, Hotez says, rests with the anti-vaccination movement and laws that allow parents to attain non-medical exemptions to vaccination.

“The anti-vaccine movement has grown into its own political and media empire,” Hotez says. “We have to work to close non-medical exemptions, especially in the 18 states allowing non-medical vaccine exemptions for personal or philosophical beliefs.”

The first step to reversing the damage is to dismantle the anti-vaccine media empire, he says, adding that social media and online retailers that sell anti-vaccination materials are major contributors to the problem. Critics may argue that stifling anti-vaccination commentary or limiting sales of anti-vaccine materials violates the First Amendment, but Hotez likens it to any retailer making decisions about the types of products they are willing to sell.

Deliberate predation is also a problem, he says, and involves the targeting of specific groups to lower vaccination rates by anti-vaccination promoters. He uses a measles outbreak in an Orthodox Jewish community, and in a Somali community in Minnesota as examples.

“They handed out pamphlets and held town hall meetings and made calls,” Hotez says. “What they do is they are trying to make headway any way they can.”

Another hurdle is the absence of a robust pro-vaccination campaign, he says.

“Australians have done this. They put out a $12 million public service campaign,” Hotez says. “We need to have a more visible national public health leadership. Right now, the default is the defense of vaccines falling to a handful of academic pediatricians.”

Twenty years of allowing the anti-vaccination movement to grow unopposed has created the problem, he says, and it’s now to the point where it’s difficult to get reliable vaccination information online.

“Parents are the victim, and pediatricians are under siege,” he says. “They are keeping up, but they are not keeping up at the pace of the misinformation. There’s a whole anti-vaccination movement out there that we have to start chipping away at.”

Hotez says there is little transparency on vaccination estimates outside of school entry records and outbreak information, so it makes it difficult to tackle the problem.

“There’s not as much transparency as we would like,” he says, adding that there are at least 64,000 unvaccinated children in Texas alone, with no information on the vaccine exemption rates among individual public schools or the more than 300,000 children that are homeschooled in Texas. In an article published in PLOS Medicine, Hotez’s team recently identified more than 100 pockets of unvaccinated children, including 15 urban hot spots across the country.

“We didn’t realize at the time that we were developing a measles outbreak map, but it’s started to happen in those area already,” Hotez says. “That’s the battleground. That’s where we’re going to see measles epidemics, where teenaged girls are being denied the HPV vaccine, and we really have to double down our efforts in these areas.”

There is hope, though, says Hotez, with the right support and education.

“If there’s adequate political will, I think we could turn this around in 18 months,” he says.