People believe the government when they confirm that there has been a conspiracy

While the 1964 Warren Commission report concluded that no conspiracy was involved in the assassination of President John F Kennedy, in 1979 a US House Committee found that there may have been a conspiracy around Kennedy’s death after all. In new research, Brian Robert Calfano uses this latter report to determine how people react when a government confirms that there has been a conspiracy around an event. He finds that when a conspiracy is confirmed in this way, people are more likely to believe that there has been a conspiracy and to seek out more media information about the event.

While the 1964 Warren Commission report concluded that no conspiracy was involved in the assassination of President John F Kennedy, in 1979 a US House Committee found that there may have been a conspiracy around Kennedy’s death after all. In new research, Brian Robert Calfano uses this latter report to determine how people react when a government confirms that there has been a conspiracy around an event. He finds that when a conspiracy is confirmed in this way, people are more likely to believe that there has been a conspiracy and to seek out more media information about the event.

A significant percentage of Americans may believe in conspiracies at given times and for different psychological and ideological reasons. One overlooked question, however, is how the public responds when the government, rather than discouraging conspiratorial talk, confirms that the conspiratorial explanation is in fact true. Traditionally, portions of the public might expect that “the government” was involved in the conspiracy, refused to acknowledge that a conspiracy existed, and covered it up. However, what I term a “government-corroborated conspiracy” may be decidedly different in effect.

JFK and the finding of a conspiracy

In new research, I used two randomized experiments that introduced media information about the US government’s official findings on President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963. The 1964 Warren Commission report named Lee Harvey Oswald as Kennedy’s lone assassin. Perhaps as a result, conspiracy theories gained popularity in public discussion of Kennedy’s death.

Critically, however, the government did conclude later that a conspiracy existed involving more than Oswald. In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations found Kennedy’s death to be the result of a probable conspiracy (although the committee could not name additional conspirators). This report is a rare example of government confirming the notion of conspiracy, which makes it a useful test case for public reaction.

Understanding the effects of exposure to the House report findings might be problematic in that those alive during Kennedy’s assassination may have heavily formed perceptions of the event and its causes. Other factors being equal, traditional college-age students have a relatively good chance of lacking event familiarity. Therefore, I used two subject pools: traditional college-age students (conducted in a university computer lab in November 2013) and a sample of the general public (conducted in April 2019). Subjects in both pools were randomly assigned exposure to news about the 1979 House Select Committee report to assess (1) opinion on whether the assassination was a conspiracy; (2) the extent to which subjects are inclined to peruse media information about the assassination using a mock Google News search exercise. Utilizing unobtrusive media measures, I presented subjects with one of two mock Google News search pages referencing the “Kennedy assassination.”

“mysterious conspiracy” by Tim is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0.

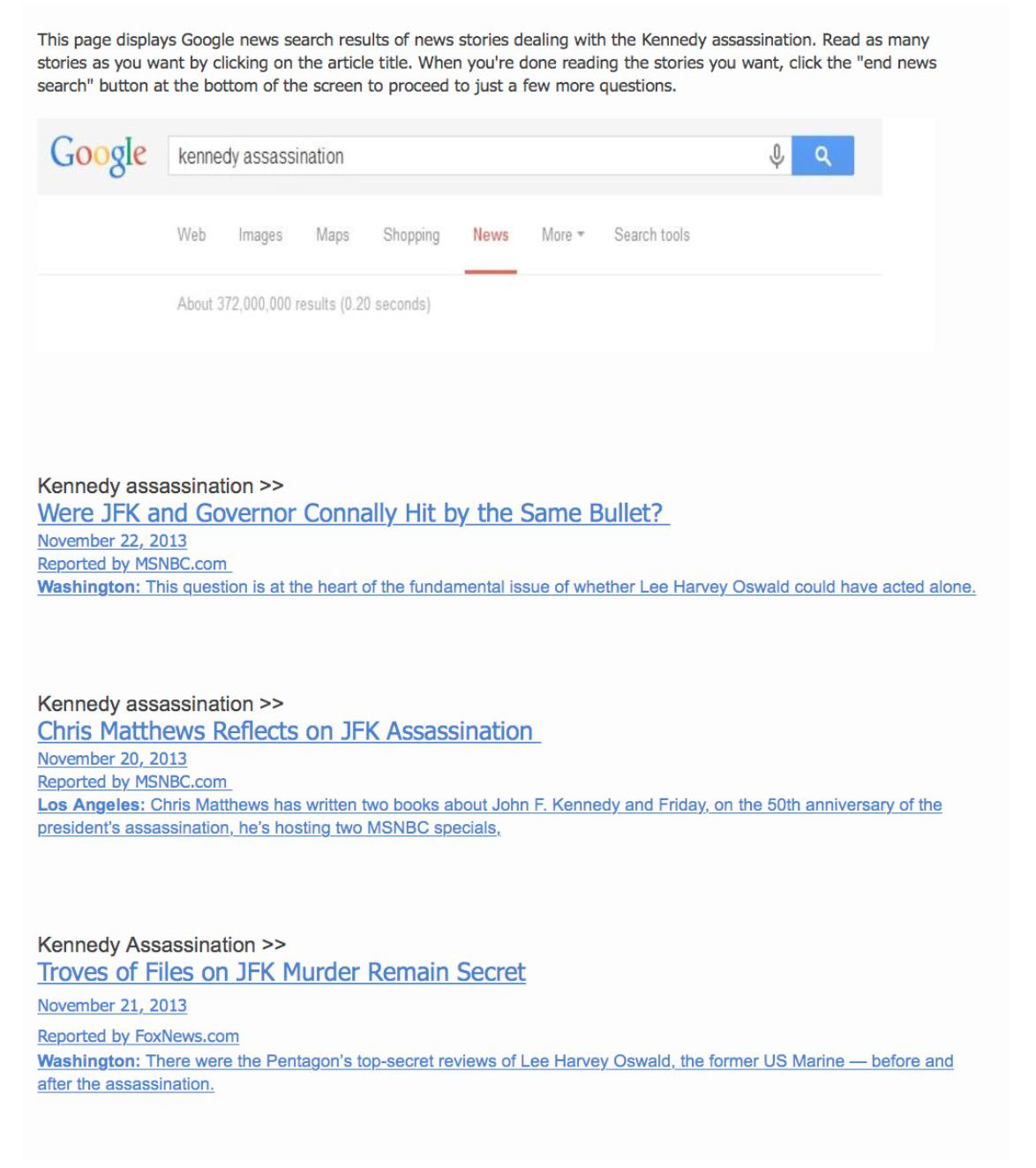

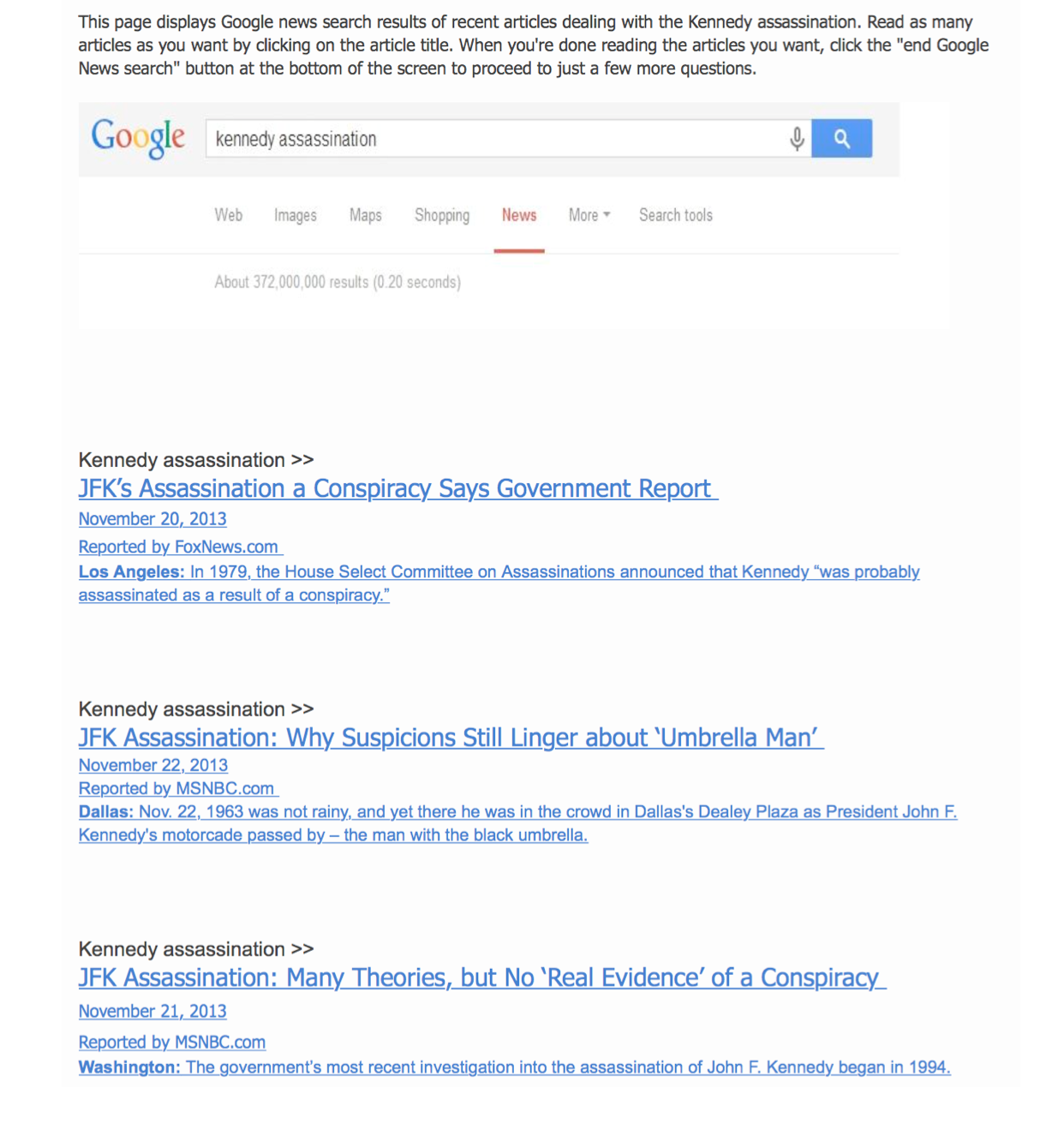

The control condition, part of which is depicted in Figure 1, contained 10 news-search items featuring actual stories about the assassination. The randomly ordered story mix included retrospectives of the 1963 events, perspective pieces about Kennedy, and the “traditional” conspiratorial material usually referenced with the assassination. The alternative (or “treatment”) condition also included a random assortment of 10 stories, eight of which were the same as for the control screen. However, two of the stories made clear mention of the finding of the 1979 Committee report of a probable conspiracy in its headlines and opening sentences (both of which were visible to all treated subjects without having to click on the story link). Figure 2 shows a portion of the treatment-condition screen.

Figure 1 – Partial image of Google News control condition

Figure 2 – Partial image of Google News treatment condition

The internet software recorded the number of story-link clicks and the order in which the clicks were made (i.e., without subjects’ knowledge). Following exposure to their assigned search page, subjects were taken to a short series of questions about their reactions. Statistical effects were modeled featuring direct treatment effect comparisons and adjustments for subject sex, race, age, partisan identity, political interest, and political knowledge.

Considering news about a “broader plot”

My treatment-only model shows that student subjects exposed to this version of the Google News search had a 16 percent increase in the probability of believing the assassination to be “the work of a broader plot,” whereas the increase was 26 percent among the national sample.

Even with the unobtrusive nature of its visual treatment display, news about the House Committee finding had a robust effect on subjects across both samples. Those exposed to the treatment version of the news-search items increased the number of stories clicked by 1.59 among the student sample and 0.92 among the national sample.

My results are evidence that subjects in separate samples were both interested in the government’s finding of a conspiracy to kill Kennedy and were moved to agree with the notion that the assassination was the work of a broader plot when exposed to information about the House report.

Beyond conspiracy

To be sure, there are scant examples of governments issuing official follow-on and contradictory reports about consequential political events like political assassinations. But the implications of my findings may surpass government reports on conspiracies. Missing from reaction to the 1979 report is any immediate partisan stake in the outcome. President Kennedy enjoys largely bipartisan support as an historical figure. By contrast, reaction to conspiratorial claims about contemporary politicians likely will be viewed from an acutely partisan lens. Moreover, to the extent that segments of the public tend to distrust government (for partisan or other reasons), the more we should expect a mediated and reduced impact of official government findings on any issue among those who find reason to be skeptical of conclusions that challenge existing beliefs.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ORkATp

About the author

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian Calfano is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and Journalism at the University of Cincinnati. He conducts research on marginalized groups, political information use, religion and politics, and journalistic coverage of political events. Brian has 40 peer-reviewed journal articles to his credit, and is the co-author of God Talk: Experimenting with the Religious Causes of Public Opinion (Temple University Press, 2013), and A Matter of Discretion: The Political Behavior of Catholic Priests in the U.S. and Ireland (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017).

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from USAPP American Politics and Policy (blog) can be found

***