WashU Expert: When the conspiracy is real

Umbrella Man. Outside agitators. Agents provocateur. As protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd continue, conspiracy theories and “false flag” charges have flown fast and furious.

But sometimes the conspiracy is real. Twitter recently suspended a fake account, established by a white nationalist group, that encouraged protesters to loot “white” neighborhoods. During the 2016 election, Russian trolls targeted African American communities.

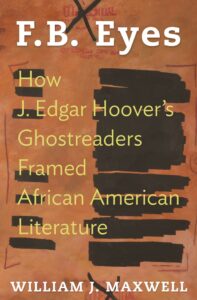

In “F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature” (2015), William J. Maxwell, professor of English in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, details a decades-long harassment campaign waged against prominent African American writers and activists.

Here, Maxwell discusses the FBI’s most egregious gambits, how targets responded and how conspiracy theories continue to shape the American imagination.

What did Hoover hope to accomplish?

In August 1919, as a lawyer all of 24 years old, J. Edgar Hoover arrived at the FBI as head of a new Radical Division (more accurately, a new Anti-Radical Division). That month also marked the end of the so-called Red Summer, a season of racial violence, urban rebellion and nationwide labor strikes, all mixed with the trauma of the “Spanish Flu” pandemic, shockingly similar to our early summer of 2020.

As first boss of the Radical Division, Hoover was charged with investigating causes of the Red Summer unrest and making sure that something like it never happened again. He didn’t accomplish the latter task, of course, but not for lack of trying. In fall 1919 and into 1920, he co-directed the anti-radical Palmer Raids — on balance, they could be called the Hoover Raids — one of the biggest mass arrests in American history and the heart of the first American Red Scare.

Hoover then launched what became a 50-year-long habit of FBI monitoring of African American writing, which he imagined as a standing invitation to race rioting and black radicalism. Late in 1919, Hoover’s Radical Division publicly issued “Radicalism and Sedition Among the Negroes as Reflected in Their Publications,” a report that reprints and reflects on some of the earliest literature of the Harlem Renaissance. Examples of that literature include Claude McKay’s legendary sonnet of black self-defense, “If We Must Die,” and militant ballads by Andy Razaf, later the lyricist of the great popular songs “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Black and Blue.”

The official and practical aim of Hoover’s close reading was to anticipate political unrest, to deter potential black literary outlaws and to reeducate their audiences. But even the first bureau agents assigned to examine African American writing also found themselves impressed and moved by it, despite themselves. The lead author of “Radicalism and Sedition,” for instance, confessed that the poetry of the Red Summer showed that the “New Negro…means business, and it would be well to take him at his word.”

Can you give us two or three examples of particularly egregious “dirty tricks” the FBI attempted?

The most egregious dirty tricks the FBI attempted followed the creation of a “COINTELPRO” — a secret counterintelligence program — aimed at “Black Nationalist/Hate Groups” beginning in 1967, as American cities burned from Newark to Detroit.

Like all of the bureau’s COINTELPROs — others were aimed at the U.S. Communist Party and “White Hate” groups — this one was calculated to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” threats to national security. What that meant in practice was a good deal of underhanded, unethical or outright illegal behavior at the highest reaches of American law enforcement.

Against the Black Panthers, the group Hoover named the “greatest threat to the internal security of the country” in 1968, COINTELPRO cultivated violence. FBI “snitch jackets,” the bogus identification of suspects as police informants, helped to provoke bloody clashes between the Panthers and other black radicals in California. In Chicago, an FBI informant was paid to provide a diagram of Fred Hampton’s apartment — he marked the spot where Hampton’s bed could be found — before the young Panther leader was effectively assassinated by a police riot squad.

Against the Black Panthers, the group Hoover named the “greatest threat to the internal security of the country” in 1968, COINTELPRO cultivated violence. FBI “snitch jackets,” the bogus identification of suspects as police informants, helped to provoke bloody clashes between the Panthers and other black radicals in California. In Chicago, an FBI informant was paid to provide a diagram of Fred Hampton’s apartment — he marked the spot where Hampton’s bed could be found — before the young Panther leader was effectively assassinated by a police riot squad.

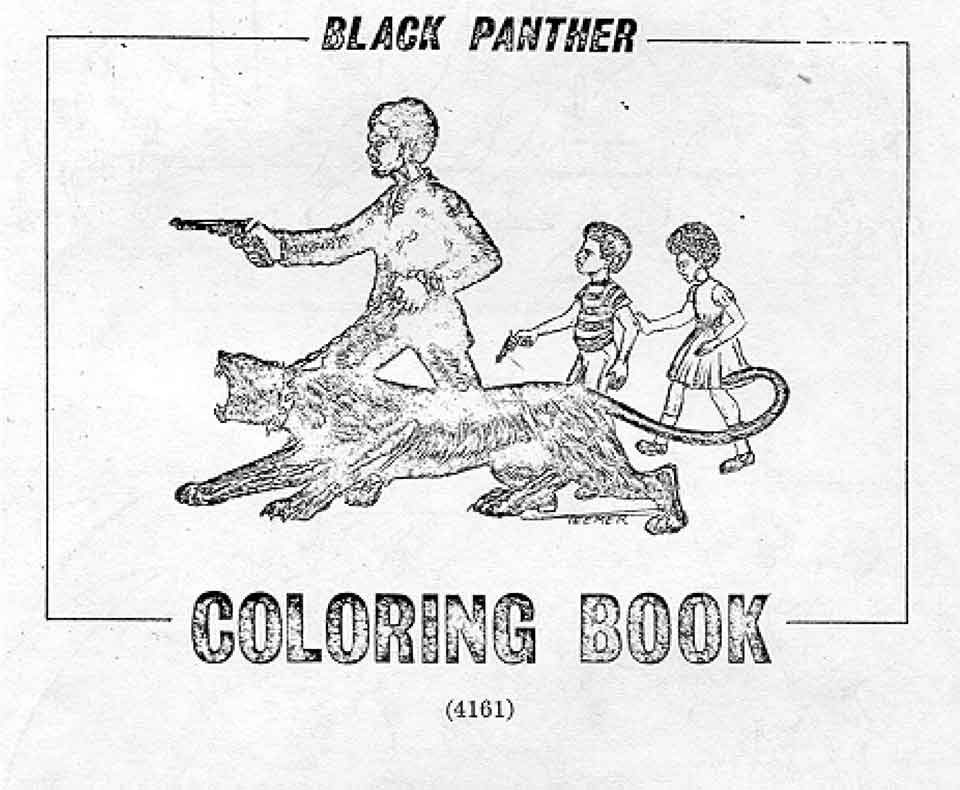

Other dirty tricks of COINTELPRO, however, were essentially literary ones, influenced in part by all the African American literature FBI readers had consumed since the Harlem Renaissance. Dozens of G-Men took time in the late 1960s and early 1970s to counterfeit writing in Black Nationalist voices, from poems, to political manifestos, to dramatic prison letters. A supposed Black Panther comic, probably faked by a West Coast FBI office, was composed of 24 pages of captioned line drawings suitable for coloring: “The only good pig, is a dead pig,” etc.

Closer to home, an entire pseudo-underground newspaper, cutely titled “Blackboard,” was forged by the St. Louis FBI field office and falsely attributed to the Black Student Union at Southern Illinois University. “Mailed anonymously by Special Agents,” reported the field office, a run of the paper was “sent to virtually every black activist organization and Black Nationalist leader in the area.”

Counterintelligence work often calls on skills also necessary for imaginative writing: artifice, impersonation, what Aristotle classically called the “imitation of an action,” etc. In the case of the FBI’s “Black Hate” COINTELPRO, these analogies sometimes grew into identities, and counterintelligence became a lesser branch of literature.

How did Hoover’s targets respond? Were they aware of the surveillance? Can you say a few words about the costs exacted, or the experimental approaches they might have inspired?

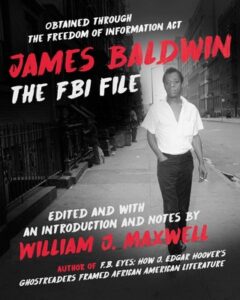

In my book “James Baldwin: The FBI File” (2017), I document one influential example of the fact that African American authors were often too aware of FBI surveillance and counterintelligence. Decades before the Black Lives Matter movement returned Baldwin to prominence, Hoover’s bureau considered him the most dangerous broker between black art and black power. Baldwin’s 1,884-page FBI file, covering the period from 1958 to 1974, was the largest compiled on any African American artist of the Civil Rights era. It shows that the FBI anxiously tracked Baldwin’s movements, writings, speeches, phone conversations and sexual preferences.

But it also demonstrates that Baldwin defiantly spied back at Hoover and company — and was hell-bent on letting the FBI know that he was doing so. Starting in 1963, Baldwin publicly warned, in multiple interviews, that he was planning a book “on the FBI and how it treats Negroes. It will be called ‘The Blood Counters,’ which is the Negroes’ nickname for the FBI.”

But it also demonstrates that Baldwin defiantly spied back at Hoover and company — and was hell-bent on letting the FBI know that he was doing so. Starting in 1963, Baldwin publicly warned, in multiple interviews, that he was planning a book “on the FBI and how it treats Negroes. It will be called ‘The Blood Counters,’ which is the Negroes’ nickname for the FBI.”

“The Blood Counters” was never completed, nor was it necessarily meant to be. But Baldwin’s decision to threaten its appearance shows that FBI harassment of black authors did not immediately silence them. Just the opposite, in dozens of cases. One of the understudied features of modern African American literature, in fact, is that so many of its creators knew that their readership contained FBI agents. From McKay, to Langston Hughes, to Ralph Ellison, to Nikki Giovanni, to Sonia Sanchez, black writers explicitly wrote back to the FBI, reworking the burden of Hoover’s spying into fresh narrative stances or new literary subgenres from the novelistic “anti-file” to a whole set of Black Arts-era “Hoover poems.”

A few lines of Richard Wright’s 1949 poem “The FB Eye Blues” may capture it best:

Everywhere I look, Lord

I see FB eyes….

I’m getting sick and tired of gover’ment spies.

Sick and tired — but also inspired.

For contemporary readers navigating the thicket of online disinformation, are there any lessons to be drawn from the writers who survived Hoover’s attacks?

Not everyone’s an author of Baldwin’s fame, talent and bravery, of course! But we can learn from him that becoming the subject of surveillance and disinformation is not intellectually fatal: these things have painful costs, including self-censorship, but liberating self-expression can also withstand and exploit them.

The history of false-flag operations and other dirty counterintelligence tricks is now so ingrained in the American imagination that it’s become a first-resort narrative frame.

William J. Maxwell

One traditional irony of literary counterintelligence, so to speak, is worth recalling in the confusing present: As Tacitus, the Roman historian phrased it, “genius chastised grows in authority,” and writers (and citizen-speakers) subjected to state interference can paradoxically gain confidence and influence through the experience. It’s when no one cares enough to spy and imitate and dissimulate that we know our speech may be too safe for comfort.

A final observation less directly tied to the FBI and African American literary history: Though I’m almost certain that there are federal informants seeded within the protest networks responding to the death of George Floyd, this federal government seems less interested in covertly obtaining counterintelligence than in overtly indicting its enemies through it. In other words, a powerful instinct of this Department of Justice is to blame the protests on Antifa infiltrators posing as protestors. (Some voices supporting the protests, of course, have been eager to blame late-night violence on the Boogaloo Boys — has there ever been a less appropriate name? — and other white supremacists posing as protestors.)

The point is this: The history of false-flag operations and other dirty counterintelligence tricks is now so ingrained in the American imagination that it’s become a first-resort narrative frame, an instant plotline for spinning the meaning of a time of dizzying historical upheaval.