If the Deep State hates Trump, why aren’t more officials speaking out like Bolton?

President Donald Trump and his allies have continually railed about how the “Deep State” of unelected national security bureaucrats has quietly worked to undermine the Trump presidency.

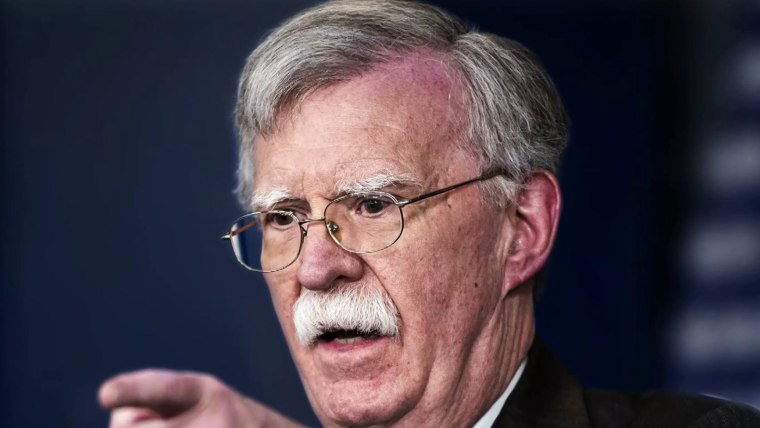

But the new allegations in a book by former national security adviser John Bolton turn that formulation on its head. If Bolton is to be believed — Trump calls him a liar — plenty of career diplomats, soldiers and spies kept quiet as they watched Trump abuse his office.

In Bolton’s telling, members of the so-called deep state, including senior intelligence and defense officials, knew about actions by Trump that were unethical, if not illegal, and said nothing. That would mean the press, the public and House impeachment investigators were kept in the dark.

The reason more insiders didn’t speak out are complex, according to a former senior national security official who served for years in the Trump administration and faced the choice on a near daily basis. But broadly, the official said, unelected national security bureaucrats tend to give great deference to the president’s policy choices, and the line between bad decisions and abuse of office is not a clear one.

“Sometimes you ask yourself: Is that malfeasance, or is that just something so dumb that you know it’s not going to happen?” the former official said.

The American system of government “has developed to give the president tremendous leeway to set policy,” said John Gans, author of a book about the White House National Security Council. “Those in the executive branch are expected to kind of nod their heads and say, ‘OK.’ There really isn’t a whistleblower system at the White House.”

Officials senior enough to be in meetings with the president don’t tend to use formal whistleblower channels anyway. Such people have long deployed anonymous leaks to the news media to flag decisions or behavior they deemed problematic.

During the Trump administration, many current and former government officials have anonymously recounted startling episodes to journalists and authors, such as Trump providing classified information to Russian officials in the Oval Office or his calling military leaders “losers” in reference to the war in Afghanistan. Once-senior officials, including former chief of staff John Kelly and former Defense Secretary James Mattis, have recently publicly questioned the president’s fitness for office, though their decisions to do so came long after they departed.

But Bolton makes a very specific case, alleging a pattern of behavior by Trump to use his presidential power in foreign affairs to further his private interests — exactly the charges in an impeachment proceeding narrowly focused on Ukraine. Bolton says the pattern went well beyond one country.

During face-to-face meetings, Trump asked the Chinese president to help get him re-elected, Bolton writes, and promised the Turkish president that he would “take care of” a Justice Department investigation deemed harmful to Turkey when he could replace Obama-appointed prosecutors with “his people.” If those exchanges happened, Bolton could not have been the only official aware of them. (Trump and one of the officials present at the summit with Chinese President Xi JinPing, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, dispute Bolton’s account.)

Bolton says Trump was willing to waive penalties on a Chinese firm, ZTE, to help with trade talks he believed would help him politically. He writes of briefing Attorney General William Barr on Trump’s “penchant to, in effect, give personal favors to dictators he liked.”

Trump hasn’t spoken to the specifics, but he has denied exploiting his office for personal gain.

Bolton also asserts people across the government knew the central premise of the impeachment case against Trump was true — that the president indeed had conditioned aid to Ukraine on that government’s willingness to do him a political favor by announcing an investigation into his opponent, an allegation of quid pro quo that Trump denies.

“I think Secretary [of State Mike] Pompeo understood,” Bolton told ABC News this week. “I think the Pentagon understood. I think the intelligence community understood. I think people in the White House understood.”

Yet in the end, only a handful of national security officials were willing to testify to that during impeachment proceedings. Only one — the whistleblower — came forward voluntarily, before the process began. Spokespersons for the CIA, director of National Intelligence and State Department declined to comment.

In his book, Bolton faults House impeachment managers for failing to investigate Trump’s “ham-handed involvement in other matters — criminal and civil, international and domestic — that should not properly be subject to manipulation by a president for personal reasons (political, economic, or any other).” He calls that “impeachment malpractice.”

That criticism sidesteps the fact that the impeachment inquiry kicked off when a lone junior CIA officer decided to file a written complaint to an inspector general about Trump’s alleged extortion of Ukraine. No similar whistleblowing efforts have come to light about Trump’s conduct with China or Turkey.

Bolton himself kept quiet for nearly two years, declining to testify in the impeachment hearing. He seeks to justify that by arguing that Democrats mishandled impeachment proceedings and that his testimony in the Senate wouldn’t have changed anything.

Critics are unconvinced.

“I think what Bolton did was shameful,” said Brian Katulis, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank. “He sat on this information for two years so he could write a book.”

If others besides Bolton are uncomfortable with what they have witnessed inside the Trump White House, why haven’t they come forward with specifics?

Look no further than what has happened to the few who have done so, experts say. Lawyers for the CIA whistleblower said publicly that he had to be protected by a security detail after the president and his Republican allies called him a traitor and a spy. Trump allies in Congress sought to put his name into the public record.

Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, who testified against Trump during the impeachment hearings, was dismissed from his job at the White House and has found his promotion to full colonel in limbo as the Pentagon worries the White House will oppose it, two defense officials told NBC News.

“You see what happens to the people who speak up,” the former senior national security official said.

“This whistleblower followed the law every step of the way and look at what they got for it,” said Liz Hempowicz, director of public policy at the Project on Government Oversight, a good-government advocacy group. Hempowicz said the already weak federal whistleblower system has disintegrated under Trump, noting the board that rules on employee disputes with management has never had enough members to make such rulings during the Trump administration.

But even for those with courage enough to brave the personal repercussions, there often is another dilemma: whether they can do more good by truth-telling or remaining in their jobs.

“Clearly people made calculations: Do you want to keep serving a president and keep our institutions intact? Or does behavior that’s so outlandish cause you to resign and report it?” said Marc Polymeropoulos, a retired CIA officer who served in senior agency roles during the first part of the Trump administration.

“There was a lot of angst about POTUS interactions with any head of state — foreign visits or phone calls,” he said.

CIA Director Gina Haspel, for one, is seen by former colleagues and congressional observers as someone who is trying at all costs to remain at the helm of a powerful spy agency that she believes could suffer severe damage in the wrong hands.

“Thankfully, CIA has remained stable in this and that will be Gina’s legacy,” Polymeropoulos said.

Haspel was criticized for failing to speak out when Trump was bashing the CIA’s Ukraine whistleblower. But she appears to have helped defuse what has been an extremely contentious relationship between Trump and the intelligence community.

“Haspel has figured out how to not to piss off the president and keep the agency from running off the rails,” added a congressional aide who works on intelligence matters. “Everyone recognizes it’s a very difficult position she is in.”

Haspel’s general counsel made what she believed was a criminal referral after the CIA whistleblower brought his complaints to her, but the agency avoided becoming entangled in the impeachment proceedings. That’s in part because Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., the Intelligence Committee chair who presided over impeachment in the House, believed it was important to keep the intelligence agencies away, as much as possible, from what turned into a vicious partisan battle, according to a person familiar with his thinking. He wanted to keep the focus on the president’s alleged abuse of office, the person said.

But if Bolton is correct that Trump broadly sought to leverage foreign policy for political gain, it’s hard to imagine the intelligence agency leaders did not become aware of it. They not only sit in high-level White House meetings, but they also spy on foreign officials who discuss what the American government is saying and doing.

“If the CIA learns of something that is an illegal act by a government official, it has an obligation to forward that information to the Department of Justice,” said former CIA Director John Brennan, an NBC News contributor. “If it’s an issue of ethics and appropriateness and one’s moral compass, then it’s more of a personal choice. Fortunately, as director, I never had to make this choice.”

It’s difficult from the outside to judge how senior officials are dealing with the turmoil inside the Trump administration, said John McLaughlin, a former deputy CIA director who served under former Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

“What you’re going to get when this administration is over is a tidal wave of memoirs, the theme of which will be, ‘You don’t know how much worse it would have been if I hadn’t been there,’” he said.

“The question is, at what point are you enabling it more so than preventing bad things from happening?”

CORRECTION (July 3, 2020, 6:07 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misspelled the last name of a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. He is Brian Katulis, not Katullis.