What makes one person more likely than another to believe #fakenews and conspiracy theories about COVID-19?

Think before you click.

People who get their news from social-media platforms like Facebook FB, +1.80% and Twitter TWTR, +4.94% are more likely to have misperceptions about COVID-19, according to new study led by researchers at McGill University in Montreal. “Those that consume more traditional news media have fewer misperceptions and are more likely to follow public health recommendations like social distancing,” the paper published in the latest issue of Misinformation Review concluded.

The likes of Twitter and Facebook have increasingly in recent years become the primary sources of news, and misinformation, for people around the world, the study said. “In the context of a crisis like COVID-19, however, there is good reason to be concerned about the role that the consumption of social media is playing in boosting misperceptions,” says co-author Aengus Bridgman, a Ph.D. candidate in political science at McGill University.

“ There is good reason to be concerned about the role that the consumption of social media is playing in boosting misperceptions. ”

Even after adjusting for demographics such as scientific literacy and socioeconomic differences, those who regularly consume social media rather than traditional media were less likely to observe social distancing and to perceive COVID-19 as a threat. “There is growing evidence that misinformation circulating on social media poses public health risks,” says co-author Taylor Owen, an associate professor at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University.

The researchers looked at the behavioral effects of exposure to fake news by combining social-media news analysis and survey research. They combed through millions of tweets, thousands of news articles and a nationally representative survey of Canadians to answer: “How prevalent is COVID-19 misinformation on social media and in traditional news media? Does it contribute to misperceptions about COVID-19? And does it affect behavior?”

The social-media platforms have been criticized for their failures to stop the spread of misinformation, especially concerning elections and the coronavirus pandemic, despite a number of new policies enacted since Russia used the platforms to interfere in the 2016 elections. In May, Twitter marked tweets by President Donald Trump with a fact-check warning label for the first time, after the president falsely claimed mail-in ballots are “substantially fraudulent.” (He has continued to make such claims on social media and elsewhere.)

Last week, social-media sites attempted to quash a video pushing misleading information about hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment — which led to Twitter’s partially suspending Donald Trump Jr.’s account. The video featured doctors calling hydroxychloroquine — a drug used to treat malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis for decades — “a cure for COVID,” despite a growing body of scientific evidence that has not shown this to be true.

Some outlandish and unsubstantiated rumors about COVID-19 persist. To adherents of such beliefs, it’s a dastardly bioweapon designed to wreak economic armageddon on the West; a left-wing conspiracy to damage the re-election prospects of Trump; a virus that leaked from a Wuhan, China, laboratory, perhaps with intent. Paranoia politicizes a global public-health emergency and distract from potentially life-saving measures to contain and/or slow the spread of coronavirus, health professionals say.

In April, the president floated the idea of using ultraviolet light inside the body or a disinfectant by “injection” as a treatment for coronavirus — “I see the disinfectant where it knocks it out in a minute. One minute. And is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning?” — a suggestion doctors called “dangerous.” (The next day, Trump claimed he was not being serious: “I was asking a question sarcastically to reporters like you just to see what would happen.”)

As of Thursday, COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2, had infected at least 18.8 million people globally and 4.8 million in the U.S. It had killed over 707,905 people worldwide and at least 158,256 in the U.S. The disease is experiencing a resurgence in southern and western states. Cases in California hit 530,606 and deaths reached 9,708 as it reported 3,624 new cases Wednesday and 100 new deaths. New York has the most fatalities (32,754) followed by New Jersey (15,842).

The stock market has been on a wild ride in recent months. The Dow Jones Industrial Index DJIA, +0.12%, the S&P 500 SPX, +0.52% and Nasdaq Composite COMP, +1.42% closed higher Wednesday, as investors awaited round two of a fiscal stimulus.

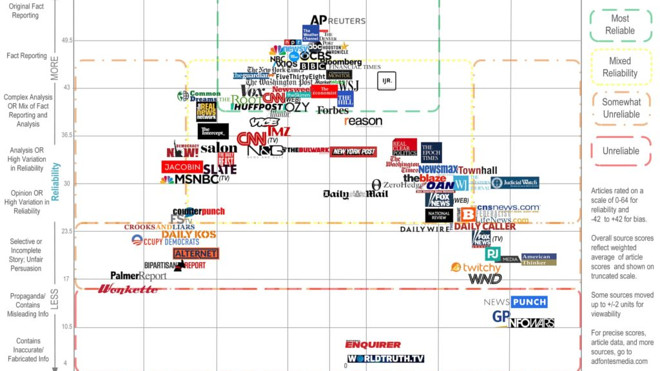

Big challenges remain for 21st-century journalism, too. Traditional journalism, according to a study released last year, has been shedding objectivity. Researchers found a major shift occurred between 1989 and 2017 as journalism expanded beyond traditional media, such as newspapers and broadcast networks, to newer media, including 24-hour cable news channels and digital outlets. “Notably, these measurable changes vary in extent and nature,” they concluded.

“Our research provides quantitative evidence for what we all can see in the media landscape,” said Jennifer Kavanagh, a senior political scientist at RAND, a nonpartisan think tank in Santa Monica, Calif., and lead author of the report on “Truth Decay,” on the declining role of facts and analysis in civil discourse. “Journalism in the U.S. has become more subjective and consists less of the detailed event- or context-based reporting that used to characterize news coverage.”

“ ‘Journalism in the U.S. has become more subjective and consists less of the detailed event- or context-based reporting that used to characterize news coverage.’ ”

The analysis — carried out by a RAND text-analytics tool previously used to identify support for and opposition to Islamic terrorists on social media — scanned millions of lines of text in print, broadcast and online journalism from 1989 (the first year such data were available via Lexis Nexis) to 2017 to identify usage patterns in words and phrases. Researchers were then able to measure these changes and compare them across all digital, media and print platforms.

Researchers analyzed content from 15 outlets representing print, television and digital journalism. The sample included the New York Times, Washington Post and St. Louis Post-Dispatch, CBS US:CBS, ABC DIS, -0.62%, CNN T, -0.07%, Fox News FOX, +0.85% FOXA, +0.68%, MSNBC CMCSA, +0.38%, Politico, the Blaze, Breitbart, Buzzfeed Politics, the Daily Caller and the Huffington Post. They found a “gradual and subtle shift” between old and new media toward a more subjective form of journalism.

Before 2000, broadcast-news segments were more likely to include relatively complex academic and precise language, as well as complex reasoning, the researchers said. After 2000, however, broadcast news became more focused on on-air personalities and talking heads debating the news. (The year 2000 is significant as ratings of all three major cable networks in the U.S. began to increase dramatically.)

Traditional newspapers made the least dramatic shift over time, the study observed. “Our analysis illustrates that news sources are not interchangeable, but each provides mostly unique content, even when reporting on related issues,’’ said Bill Marcellino, a behavioral and social scientist with RAND and co-author of the report. “Given our findings that different types of media present news in different ways, it makes sense that people turn to multiple platforms.”

It’s not the only report to find a shift toward opinion and subjectivity in news. “Tumultuous news cycles have made an impact on global opinions regarding media,” according to the 2019 U.S. News & World Report’s 2019 countries ranking. Some 63% of people say that there are no longer any objective news sources they can trust. What’s more, more than 50% agree that political and social issues around the world have gotten worse over the past year.

That survey drew on answers from 20,301 people around the world. Republican baby boomers were found to be more likely to share fake news on Facebook in the study. Why? One theory puts the emphasis on this group’s age: As they didn’t grow up with technology, they may be more susceptible to being fooled in an online environment. (Case in point: the variety of scams that have had success with older Americans by preying on their lack of familiarity with how computers and technology work.)

Key Words: Political-communication scholar has a catchy new name for fake news: V.D.

Here’s that chart: