How to spot fake news on Facebook and Twitter before the 2020 election

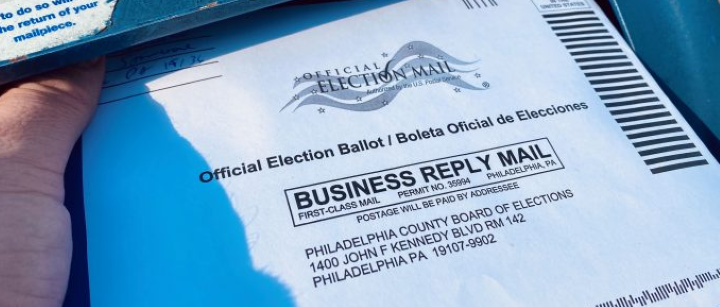

In this election season, misinformation seems to be everywhere. Concern about the state of the post office and absentee voting has fueled misleading, viral images of collection boxes. Racist conspiracy theorists have brought back birtherism to attack vice presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris. President Donald Trump has continued to spread falsehoods about mail-in voting, hydroxychloroquine, and whether children can get Covid-19.

Under increasing pressure over the past four years, social media platforms have begun cracking down on various forms of misinformation. But an array of critics that includes politicians, the public, and activists say these companies’ efforts fall short. It’s still pretty easy to spread misinformation and conspiracy theories on the web.

“I wouldn’t rely too much on social media companies to do this hard work for us,” Sam Rhodes, who studies misinformation at Utah Valley University, told Recode. “Not only are they not up to the task, they don’t really seem that interested in it.” Rhodes added that social media companies seem to take action more often against specific examples of misinformation after they’ve already gone viral and grabbed the media’s attention.

Election Day is approaching, and you’ll likely have to use your own judgment to identify misleading or downright false content on social media. So how can you prepare? Plenty of outlets have written guides to spotting misinformation on your feeds — some great resources are available at The Verge, Factcheck.org, and the Toronto Public Library.

You can go beyond that by minimizing the chance that you’ll come across misinformation in the first place (though there’s no guarantee). That means unfollowing less-than-ideal sources and taking steps to prioritize legitimate ones. It also means talking to friends or family whose feeds might be more vulnerable to misinformation than yours, so they can take the same steps.

Misinformation on your feed can take many forms

Links that lead to seemingly-normal-but-not news articles can contain misinformation, but that’s not its only source. A family member might share misinformation as a status update or through a text message. It could also come from a discussion in a private online group or in the form of an image or meme. Importantly, misinformation can switch from platform to platform, from format to format, and can jump from obscure sites into the mainstream discourse relatively quickly. And yes, misinformation can appear in political advertisements, as well as posts from the president of the United States.

But much of this misinformation won’t be deleted because social media companies don’t usually consider inaccurate information to be enough of a reason to remove a post. While Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube might remove a post if it could cause physical harm or interfere in an election, the platforms generally don’t ban misinformation itself.

Facebook, at least, does some automatic labeling of posts that appear to be about voting information, pointing readers to vetted sources. Social media companies also have broader fact-checking programs, but these are hardly a cure-all when it comes to preventing the spread of misinformation. Fact-checkers can’t easily find content that’s shared in private groups and messages, and the tools fact-checkers have to flag misinformation are limited. The purpose of Facebook’s fact-checkers, for instance, is to apply labels to — and reduce the spread of — misinformation; fact-checking doesn’t itself lead to the content being taken down.

And they don’t label everything. A recent report from the activist nonprofit Avaaz found that just 16 percent of health misinformation on Facebook analyzed by its researchers carried a warning from fact-checkers. And Facebook has also removed fact-checking labels in response to pressure from conservative groups.

Here’s what you can do to limit your own exposure to misinformation

Your social feeds are most shaped by who you follow, so following reputable sources of information and news is probably your best bet. Unfollowing known sources of misinformation, even if that includes close friends and family, is probably worth considering as well. If you want to get ahead on fact-checking, you might consider following fact-checking organizations directly, ensuring their fact-checks are in your feed. You can check out this list of organizations that have signed on to the fact-checking principles established by the International Fact-checking Network, or this list of US-focused fact-checkers from American University.

There are also media-trust tools, which can help flag known disreputable sources. NewsGuard, for instance, provides resources for tracking particular sources of misinformation on the web.

Something to watch out for: If you keep seeing the same claim from a bunch of different sources that generally support your political views, you should stay alert. According to Princeton political science professor Andy Guess, “That is when your alarm bells should be going off.” If information supports the side we agree with, we’re more likely to believe it and less likely to think critically about it.

Repetition also makes us more likely to believe something is true. “One of the real dangers of social media is that there could be one news report or one claim that gets retweeted a bunch and trickles down to people’s feeds, in ways that obscure that this all came from a single source,” Guess told Recode. “So when you see it multiplied, that can make you falsely confident that something is true.”

With all that in mind, the platforms do give you tools to help manage your feeds and prime them for accurate information.

Let’s start with Facebook. One of the first things any Facebook user can do is set your account to prioritize 30 reputable sources — meaning trusted news organizations and fact-checking outlets — in your News Feed. This will make those accounts more likely to appear high up in your feed when you log on. And, of course, you can unfollow or block pages if you spot them sharing misinformation. If that’s too aggressive for you, there are other tools that allow you to hide and “snooze” bad sources — a strategy that Rhodes, from Utah Valley University, recommends for family members that repeatedly share misinformation.

It’s important to remember that Facebook in 2018 shifted its algorithm to prioritize posts from friends and family over public content in the News Feed, which means that if you don’t adjust your settings, a conspiracy-curious Facebook post from your mom might get higher placement in your feed than a reported-out story posted by the Associated Press Facebook page.

When you’re scrolling through your News Feed, you can also keep an eye out for the “News Feed Context Button,” which provides extra information for some links and pages that share content on your feed. If an outlet doesn’t come up as having a formal presence on Facebook — and doesn’t have a Wikipedia page — that’s probably a good sign they’re not an established outlet worth trusting.

In addition to its fact-checking and voting information labels, Facebook sometimes offers other labels, called interstitials, that are designed to provide more context to a piece of content, mainly emphasizing that an article about Covid-19 is very old and probably out-of-date. If an account keeps sharing out-of-date news headlines, they might be worth unfollowing: Old stories can be misleading and lack critical, new information. If you receive an alert from Facebook that you’ve previously interacted with fake news, it might be worth going back to unfollow that source, too.

If you see something flagged as false pop up in your page, you can also check out the “Why Am I Seeing This” feature, which can help find the root of a particular concerning post. That might show you that you’re in a group where such misinformation is posted, or if your frequent commenting on a particular account is boosting its presence in your feed.

You can also turn off political ads — which can also be a source of misinformation — though you may risk missing ads from lesser-known candidates.

If you use the Facebook News App, you can also choose which outlets to prioritize in its settings, or leave what you see up to the platform’s curation. If you run any Facebook groups, it’s worth keeping an eye out for “group quality” notices that the company might display on the pages. That’s where Facebook will tell you whether posts in your group have been flagged for sharing false news. If you’re in a group that keeps posting misinformation, consider leaving that group.

Next up is Twitter. Again, what you see depends largely on who you follow. One way that Twitter makes controlling who you follow easier is through Lists, which are “curated groups” of accounts, like a list of news or journalism organizations. There’s also the Twitter “Topics” section, which lets you follow topics like the 2020 Election, as well as unfollow topics you’re not interested in and don’t want to hear more about. Twitter also picks up your “interests,” which you can look at and edit here.

One thing to keep in mind is that a verified Twitter account — an account that carries a little white check in a blue circle — is not guaranteed to be an accurate or legitimate source. That said, unverified accounts are probably not an ideal way of finding confirmed, breaking news. You should also keep an eye out for Twitter’s labels for state- and government-affiliated media sources. Those sources have particular motives of their own and can skew events in a particular way. Not every outlet that might have goals beyond accurate journalism in mind gets a label.

If you see a story going viral on Twitter, pay attention to what headline Twitter places in its trending box. Sometimes, the company will choose to elevate content from specific fact-checkers or news organizations that refutes a trending but false narrative. This happened, for instance, when misinformation about Sen. Kamala Harris’s eligibility to run for president went viral.

Everywhere else

Beyond steps you can take that are specific to a platform, you can apply commonsense measures, like watching for sensationalist headlines and avoiding suspicious-looking websites, some of which might be imitating the websites of real news providers. That also means clicking through an article — and looking for evidence — before actually sharing it.

“Engage very critically with what you’re reading. Check sources and then check supports, like who’s being quoted where, where the information is coming from, etc.,” Seattle-based librarian and media literacy expert Di Zhang recently told Vox’s Today Explained podcast. “[I]f it contains a claim that it has a secret, the media, the government, big business, whatever doesn’t want you to know about and that they’re the only one who has access to this information, that is a big red flag.”

Unfortunately, all these steps may not be enough to keep misinformation completely off your feed, especially when the president is spreading misinformation with near-impunity. But here’s some good news: Most people aren’t seeing outright misinformation on their feeds on a regular basis, which means that the best use for this guidance may be sending it to a loved one.

“The kinds of people who frequently encounter online misinformation tend to be in clusters, where it’s more likely to be shared and viewed,” Guess, the Princeton professor, told Recode. “There are groups of people who read a lot of it, but it’s not most people.” He added that when people share misinformation, they often do so to signal their membership with particular, highly partisan groups.

Guess also said that those who are sharing misinformation are more likely to be older, and to people who mostly read right-wing sources of information, according to his research. So if you’re not personally seeing a lot of misinformation on your feed but are close to someone who is, you might be in a better position to gently guide them toward better sources of news.

But don’t scold them. That can actually strengthen wrong beliefs. “Appeal to their reason, and also appear to appeal to their sensibilities,” said Rhodes, who recommends a script like this: “Like you, I am concerned about the election. Like you, I am concerned about the direction of this country. However, there are others sources out there that may dispute some of the facts and dispute some of the stuff that you’re talking about.”

Open Sourced is made possible by Omidyar Network. All Open Sourced content is editorially independent and produced by our journalists.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

The United States is in the middle of one of the most consequential presidential elections of our lifetimes. It’s essential that all Americans are able to access clear, concise information on what the outcome of the election could mean for their lives, and the lives of their families and communities. That is our mission at Vox. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone understand this presidential election: Contribute today from as little as $3.