Misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic – Wikipedia

Misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic

Jump to navigation Jump to search

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

Timeline

|

|

Locations

|

|

International response

|

|

Medical response

|

|

Impact

|

COVID-19 Portal COVID-19 Portal |

|

|

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Please consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. (August 2020)

|

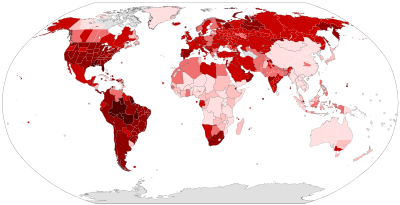

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in misinformation and conspiracy theories about the scale of the pandemic and the origin, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the disease.[1][2][3] False information, including intentional disinformation, has been spread through social media,[2][4] text messaging,[5] and mass media,[6] including the tabloid media,[7] conservative media,[8][9] and state media of countries such as China,[10][11] Russia,[12][13] Iran,[14] and Turkmenistan.[2][15] It has also been reportedly spread by covert operations backed by states such as Saudi Arabia, Russia and China to generate panic and sow distrust in other countries.[16][17][18][19] In some countries, such as India,[20] Bangladesh,[21] and Ethiopia,[22] journalists have been arrested for allegedly spreading fake news about the pandemic.[23]

Misinformation has been propagated by celebrities, politicians[24][25] (including heads of state in countries such as the United States,[26][27] Iran,[28] and Brazil),[29][30] and other prominent public figures.[31] Commercial scams have claimed to offer at-home tests, supposed preventives, and “miracle” cures.[32][33] Several religious groups have claimed their faith will protect them from the virus.[34][35][36] Some people have claimed the virus is a bioweapon accidentally or purposefully leaked from a laboratory,[37][38] a population control scheme,[39] the result of a spy operation,[3][4][40] or the side effect of 5G upgrades to cellular networks.[41]

The World Health Organization has declared an “infodemic” of incorrect information about the virus, which poses risks to global health.[2]

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

- 1 Types, origin, and effect

- 2 Accidental leakage theories

- 3 Conspiracy theories

- 3.1 Bio-engineered virus

- 3.2 Chinese biological weapon

- 3.3 Chinese espionage involving Canadian lab

- 3.4 United States biological weapon

- 3.5 Jewish origin

- 3.5.1 In the Muslim world

- 3.5.2 In the United States

- 3.6 Anti-Muslim

- 3.7 Population-control scheme

- 3.8 5G mobile phone networks

- 3.9 Polio vaccine

- 4 Misreporting of morbidity and mortality numbers

- 4.1 Alleged leak of death toll

- 4.2 Misinformation against Taiwan

- 4.3 Misrepresented World Population Project map

- 4.4 Nurse whistleblower

- 4.5 Decline in cellphone subscriptions

- 5 Disease spread

- 5.1 California herd immunity in 2019

- 5.2 Patient Zero

- 5.3 Resistance/susceptibility based on ethnicity

- 5.3.1 Xenophobic blaming by ethnicity and religion

- 5.4 Bat soup consumption

- 5.5 Large gatherings

- 5.6 Lifetime of the virus

- 5.7 Mosquitoes

- 5.8 Objects

- 5.9 Cruise ships’ safety from infection

- 6 Prevention

- 6.1 Efficacy of hand sanitizer, “antibacterial” soaps

- 6.2 Public use of face masks

- 6.3 Alcohol (ethanol and poisonous methanol)

- 6.4 Vegetarian immunity

- 6.5 Religious protection

- 6.6 Cocaine

- 6.7 Helicopter spraying

- 6.8 Vibrations

- 6.9 Food

- 7 Treatment misinformation

- 7.1 Hospital conditions

- 7.2 Herbal treatments

- 7.3 Vitamin D

- 7.4 Common cold and flu treatments

- 7.5 Animal-based products or foods

- 7.6 Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) prescriptions

- 7.7 Chloroquine

- 7.8 Hydroxychloroquine

- 7.9 Dangerous treatments

- 7.10 Untested treatments

- 7.11 Non-existent COVID-19 vaccine

- 7.12 Spiritual healing

- 8 Recovery

- 9 Other

- 9.1 Name of the disease

- 9.2 Simpsons prediction

- 9.3 United Kingdom £20 banknote

- 9.4 Hospital ship attack

- 9.5 Return of wildlife

- 10 Government

- 10.1 Argentina

- 10.2 Brazil

- 10.3 China

- 10.3.1 Mishandling of crisis

- 10.3.2 Origin of virus

- 10.3.3 Statistics on fatalities

- 10.3.4 Kazakh virus

- 10.4 Cuba

- 10.5 Egypt

- 10.6 Estonia

- 10.7 France

- 10.8 Iran

- 10.9 Mexico

- 10.10 Russia

- 10.11 Serbia

- 10.12 Turkmenistan

- 10.13 United Arab Emirates

- 10.14 United Kingdom

- 10.15 United States

- 10.15.1 Presidential

- 10.16 Venezuela

- 11 Efforts to combat misinformation

- 11.1 Social media

- 11.2 Wikipedia

- 11.3 Newspapers and scholarly journals

- 11.4 Censorship

- 12 Scams

- 13 See also

- 14 Notes

- 15 References

- 16 Further reading

- 17 External links

Types, origin, and effect

On 30 January 2020, the BBC reported on the growing number of conspiracy theories and bad health advice regarding COVID-19. Notable examples at the time included false health advice shared on social media and private chats, as well as conspiracy theories such as the disease’s origins in (Chinese) bat soup and the outbreak being planned with the participation of the Pirbright Institute.[1][42] On 31 January, The Guardian listed seven instances of misinformation, adding the conspiracy theories about bioweapons and the link to 5G technology, and including varied false health advice.[43]

In an attempt to speed up research sharing, many researchers have turned to preprint servers such as arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv, and SSRN. Papers are uploaded to these servers without peer review or any other editorial process that ensures research quality. Some of these papers have contributed to the spread of conspiracy theories. The most notable case was a preprint paper uploaded to bioRxiv which claimed that the virus contained HIV “insertions”. Following objections, the paper was withdrawn.[44][45][46]

According to a study published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, most misinformation related to COVID-19 involves “various forms of reconfiguration, where existing and often true information is spun, twisted, recontextualised, or reworked”; less misinformation “was completely fabricated”. The study also found that “top-down misinformation from politicians, celebrities, and other prominent public figures”, while accounting for a minority of the samples, captured a majority of the social media engagement. According to their classification, the largest category of misinformation (39%) was “misleading or false claims about the actions or policies of public authorities, including government and international bodies like the WHO or the UN”.[47]

A natural experiment—an experiment that takes place spontaneously, without human design or intervention—shows a potential link between coronavirus misinformation and increased infection and death. There was one instance of this reported where two similar television news shown on the same network were compared. One reported the effects of coronavirus more seriously and about a month earlier than the other. People and groups exposed to the news show reporting the effects later had higher infection and death rates.[48]

The misinformation has been used by politicians, interest groups, and state actors in many countries for political purposes: to avoid responsibility, scapegoat other countries, and avoid criticism of their earlier decisions. Sometimes there is a financial motive as well.[49][50][51] A number of countries have been accused of spreading disinformation with state-backed operations in the social media in other countries to generate panic, sow distrust, and undermine democratic debate in other countries, or to promote their models of government.[16][52][18][19]

Accidental leakage theories

A number of allegations have emerged supposing a link between the virus and Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV); among these is that the virus was an accidental leakage from WIV.[53] In January 2020, editors at the scientific journal Nature affixed a cautionary warning to an article by Richard H. Ebright who wrote about the WIV in 2017 and noted that the SARS virus had escaped from high-level containment facilities in Beijing before; the editors warned that unverified theories, unsupported by scientists, were being promoted to suggest that the WIV played a role in the COVID-19 outbreak.[54] In an interview with BBC China in February 2020, Ebright refuted several conspiracy theories regarding the WIV (e.g., bioweapons research, or that the virus was engineered), but said a laboratory leak origin could not be “completely ruled out.”[55][56] Other researchers have said that there is little chance it was a laboratory accident.[57]

A theory emerged in February 2020, alleging that the first infected person may have been a researcher at the institute named Huang Yanling.[58] Rumours circulated on Chinese social media stating that the researcher became infected and later died; this prompted a denial from WIV who released a statement that she was a graduate student enrolled at the Institute until 2015, and that she is still healthy and not patient zero.[59][58] In early April, this theory started to circulate on YouTube and was picked up by conservative media, National Review.[60][6] Disinformation researcher Nina Jankowicz from the Wilson Center, however, proposed that the lab leakage theory entered mainstream media in United States via a later documentary by The Epoch Times, propagated by news outlets.[51][a][b]

The South China Morning Post (SCMP) reported that one of the WIV’s lead researchers, Shi Zhengli, was the particular focus of personal attacks in Chinese social media alleging that her work on bat-based viruses was the source of the virus; this led Shi to post: “I swear with my life, [the virus] has nothing to do with the lab”. When asked by the SCMP to comment on the attacks, Shi responded: “My time must be spent on more important matters”.[66][c]

On 14 April, the US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Milley, in response to questions about the virus being manufactured in a lab, said “it’s inconclusive, although the weight of evidence seems to indicate natural. But we don’t know for certain.”[69] On that same day, Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin detailed a leaked cable of a 2018 trip made to the WIV by scientists from the US Embassy. The article was referenced and cited by conservative media to push the lab leakage theory.[51] Rogin’s article went on to say that “What the U.S. officials learned during their visits concerned them so much that they dispatched two diplomatic cables categorized as Sensitive But Unclassified back to Washington. The cables warned about safety and management weaknesses at the WIV lab and proposed more attention and help. The first cable, which I obtained, also warns that the lab’s work on bat coronaviruses and their potential human transmission represented a risk of a new SARS-like pandemic.”[70] Rogin’s article pointed out there was no evidence that the coronavirus was engineered, “But that is not the same as saying it didn’t come from the lab, which spent years testing bat coronaviruses in animals.”[70] The article went on to quote Xiao Qiang, a research scientist at the School of Information at the University of California, Berkeley: “I don’t think it’s a conspiracy theory. I think it’s a legitimate question that needs to be investigated and answered. To understand exactly how this originated is critical knowledge for preventing this from happening in the future.”[70] The Washington Post’s article and subsequent broadcasts drew criticism from virologist Angela Rasmussen of Columbia University, who stated: “It’s irresponsible for political reporters like Rogin [to] uncritically regurgitate a secret ‘cable’ without asking a single virologist or ecologist or making any attempt to understand the scientific context.”[51] Rasmussen later compared biosafety procedure concerns to “having the health inspector come to your restaurant. It could just be, ‘Oh, you need to keep your chemical showers better stocked.’ It doesn’t suggest, however, that there are tremendous problems.”[71] Jonna Mazet, Professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis and director of the PREDICT project to monitor emerging viruses, has commented that staff at the Wuhan Institute of Virology were trained at US labs and follow high safety standards, and that “All of the evidence points to this not being a laboratory accident.”[57]

Days later, multiple media outlets confirmed that US intelligence officials were investigating the possibility that the virus started in the WIV.[72][73][74][75] On 23 April, Vox presented disputed arguments on lab leakage claims from several scientists.[76] Scientists suggested that virus samples cultured in the lab have significant amount of difference compared with SARS-CoV-2. The virus institution[which?] sampled RaTG13 in Yunnan, the closest known relative of the nes[further explanation needed] coronavirus, with a 96% shared genome. Edward Holmes, SARS-CoV-2 researcher at the University of Sydney, explained that 4% of difference “is equivalent to an average of 50 years (and at least 20 years) of evolutionary change.”[76][77] Virologist Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, which studies emerging infectious diseases, noted the estimate that 1–7 million people in Southeast Asia who live or work in proximity to bats are infected each year with bat coronaviruses. In the interview with Vox, he comments, “There are probably half a dozen people that do work in those labs. So let’s compare 1 million to 7 million people a year to half a dozen people; it’s just not logical.”[57][76]

On 30 April, The New York Times reported that the Trump administration demanded that intelligence agencies find evidence linking WIV with the origin of SARS-Cov-2. Secretary of State and former Central Intelligence Agency (C.I.A) director Mike Pompeo was reportedly leading the push on finding information regarding the virus origin. Analysts were concerned that pressure from senior officials could distort assessments from the intelligence community. Anthony Ruggiero, the head of the National Security Council which was responsible for tracking weapons of mass destruction, expressed frustration during a video conference that the C.I.A. was unable to reach a definite explanation of the virus’s origin. According to current and former government officials, as of 30 April 2020, the C.I.A has yet to find any information other than circumstantial to bolster the lab theory.[78][79] United States intelligence officers suggested that Chinese officials tried to conceal the severity of the outbreak in early days, but no evidence has shown China attempted to cover up a lab accident.[80] One day later, Trump claimed to possess evidence of the lab theory, but offered no further details.[81][82] Jamie Metzl, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, claimed the SARS-CoV-2 virus “likely” came from a Wuhan virology testing laboratory, based on “circumstantial evidence”. He was quoted as saying, “I have no definitive way of proving this thesis.”[83]

On 30 April 2020, the US intelligence and scientific communities issued a public statement dismissing the idea that the virus was not natural, while the investigation of the lab accident hypothesis was ongoing.[84][85] The White House suggested an alternative explanation, along with a seemingly contradictory message, that the virus was man-made. In an interview with ABC News, Secretary of State Pompeo said he has no reason to disbelieve the intelligence community that the virus was natural. However, this contradicted the comment he made earlier in the same interview, in which he said “the best experts so far seem to think it was man-made. I have no reason to disbelieve that at this point.”[86][87][88]

On 4 May, the Australian tabloid The Daily Telegraph claimed that a reportedly leaked dossier from Five Eyes, an intelligence alliance, alleged the probable outbreak was from the Wuhan lab.[89] Fox News, and national security commentators in the US, quickly followed up The Telegraph story,[90][91] raising tensions within the international intelligence community.[92] The Australian government, which is part of the Five Eyes alliance, determined the leaked dossier was not a Five Eyes document, but a compilation of open-source materials that contained no information generated by intelligence gathering.[93] The German intelligence community denied the claim of the leaked dossier, instead supporting the probability of a natural cause.[94][95] The Australian government sees the promotion of the lab theory from the United States counterproductive to Australia’s push for a more broad international-supported independent inquiry into the virus origins.[92] Senior officials in the Australian government speculated the dossier was leaked by the United States embassy in Canberra to promote a narrative in Australian media that diverged from the mainstream belief of Australia.[92][93][90]

Beijing rejected the White House’s claim, calling the claim “part of an election year strategy by President Donald Trump’s Republican Party”.[96] Hua Chunying, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, urged Mike Pompeo to present evidence for his claim. “Mr. Pompeo cannot present any evidence because he does not have any,” Hua told a journalist during a regular briefing, “This matter should be handled by scientists and professionals instead of politicians out of their domestic political needs.”[96][97] The Chinese ambassador, in an opinion published in the Washington Post, called on the White House to end the “blame game” over the coronavirus.[98][99] As of 5 May, assessments and internal sources from the Five Eyes nations indicated that the coronavirus outbreak being the result of a laboratory accident was “highly unlikely”, since the human infection was “highly likely” a result of natural human and animal interaction. However, to reach a conclusion with total certainty would still require greater cooperation and transparency from the Chinese side.[100]

Amidst the WIV-conspiracy theories and the rise of anti-Chinese hate crimes, Chinese experts, media and netizens have themselves demanded transparency from the U.S. government back in March 2020, the information regarding the bio-safety level 3 and 4 violations at Fort Detrick which led the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to force closure of the U.S. Army BSL-4 laboratory at the base back in August 2019; two months before the Military World Games in Wuhan.[101] The theory that SARS-CoV-2 could possibly have leaked from Fort Detrick high-level pathogens lab was immediately and strongly rejected by the U.S. side; in an emailed response to Frederick News-Post, U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command spokeswoman Lori Salvatore stated: “That is an absolutely false claim, USAMRIID does not take part in offensive research.”[102]

On 16 May 2020, China reported that their current official position on the source of the COVID-19 virus may be summarized as follows: “The conspiracy theory about the origin of the new coronavirus has no substantive content. In fact, there is evidence to support the natural emergence of new coronaviruses, and preliminary genotyping studies have shown the relationship between the coronavirus and other bat viruses. We must be careful not to blame the rumours in an irresponsible way and use the global crisis to grab political scores”.[103][104] On 18 May 2020, an official UN investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 virus was supported by over 120 countries despite China’s objection,[105] A two-member advance team was sent to China to organise the investigation in July 2020,[106] although the team failed to visit Wuhan in their three-week stay there.[107]

Conspiracy theories

Bio-engineered virus

In 2015, Nature Medicine published a study by an international group of researchers (including Shi Zhengli who in 2019 identified SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan) on creating a chimeric virus pathogenic to humans.[108] This publication later in 2019 sparked speculations that SARS-CoV-2 is a variant of such human-engineered virus. In 2020 Nature Medicine published an article arguing against the conspiracy theory that the virus was created artificially. The high-affinity binding of its peplomers to human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) was shown to be “most likely the result of natural selection on a human or human-like ACE2 that permits another optimal binding solution to arise”.[109] In case of genetic manipulation, one of the several reverse-genetic systems for betacoronaviruses would probably have been used, while the genetic data irrefutably showed that the virus is not derived from a previously used virus template.[109] The overall molecular structure of the virus was found to be distinct from the known coronaviruses and most closely resembles that of viruses of bats and pangolins that were little studied and never known to harm humans.[110]

In February 2020, the Financial Times quoted virus expert and global co-lead coronavirus investigator Trevor Bedford: “There is no evidence whatsoever of genetic engineering that we can find”, and “The evidence we have is that the mutations [in the virus] are completely consistent with natural evolution”.[111] Bedford further explained, “The most likely scenario, based on genetic analysis, was that the virus was transmitted by a bat to another mammal between 20–70 years ago. This intermediary animal—not yet identified—passed it on to its first human host in the city of Wuhan in late November or early December 2019”.[111]

On 19 February 2020, The Lancet published a letter of a group of scientists condemning “conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin”.[112] Even so, conspiracy theories have appeared both in social media and in mainstream news outlets, and are heavily influenced by geopolitics.[113] The German Deutsche Welle produced a video in May 2020, featuring scientists from the Leibniz Association and the University of Bern, explaining, that a well made genetic manipulation of a virus could very likely not be recognized.[114]

Chinese biological weapon

Tobias Ellwood said, “It would be irresponsible to suggest the source of this outbreak was an error in a Chinese military biological weapons programme … But without greater Chinese transparency we cannot [be] entirely completely sure.”[115]

In January 2020, BBC News published an article about SARS-CoV-2 misinformation, citing two 24 January articles in The Washington Times that said the virus was part of a Chinese biological weapons program, based at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV).[1][d][e][f][g][h] The Washington Post later published an article debunking the theory, citing US experts who explained why the WIV was unsuitable for military use, that most countries had abandoned bioweapon programs as failures, and that there was no evidence the virus was genetically engineered.[121]

On 6 February, the White House asked scientists and medical researchers to rapidly investigate the origins of the virus both to address the current spread and “to inform future outbreak preparation and better understand animal/human and environmental transmission aspects of coronaviruses”.[122]

The Inverse reported that “Christopher Bouzy, the founder of Bot Sentinel, conducted a Twitter analysis for Inverse and found [online] bots and trollbots are making an array of false claims. These bots are claiming China intentionally created the virus, that it’s a biological weapon, that Democrats are overstating the threat to hurt Donald Trump and more. While we can’t confirm the origin of these bots, they are decidedly pro-Trump.”[123][i]

Chinese espionage involving Canadian lab

Some people have alleged that the coronavirus was stolen from a Canadian virus research lab by Chinese scientists. Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada said that the conspiracy theory had “no factual basis”.[133] The stories seem to have been derived[134] from a July 2019 news article[135] stating that some Chinese researchers had their security access to the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, a Level 4 virology lab, revoked after a Royal Canadian Mounted Police investigation. Canadian officials described this as an administrative matter and “there is absolutely no risk to the Canadian public.”[135]

This article was published by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC);[134] responding to the conspiracy theories, the CBC later stated that “CBC reporting never claimed the two scientists were spies, or that they brought any version of the coronavirus to the lab in Wuhan”. While pathogen samples were transferred from the lab in Winnipeg to Beijing on 31 March 2019, neither of the samples was a coronavirus, the Public Health Agency of Canada says the shipment conformed to all federal policies, and there has not been any statement that the researchers under investigation were responsible for sending the shipment. The current location of the researchers under investigation by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police is not being released.[133][136][137]

In the midst of the coronavirus epidemic, a senior research associate and expert in biological warfare with the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, referring to a NATO press conference, identified suspicions of espionage as the reason behind the expulsions from the lab, but made no suggestion that coronavirus was taken from the Canadian lab or that it is the result of bioweapons defense research in China.[138]

United States biological weapon

The Xinhua News Agency is among the news outlets that have published false information about COVID-19’s origins.

According to London-based The Economist, plenty of conspiracy theories exist on China’s internet about COVID-19 being the CIA’s creation to keep China down.[139] According to an investigation by ProPublica, such conspiracy theories and disinformation have been propagated under the direction of China News Service, the country’s second largest government-owned media outlet controlled by the United Front Work Department.[140] Global Times and Xinhua News Agency have similarly been implicated in propagating disinformation related to COVID-19’s origins.[141][142] NBC News however has noted that there have also been debunking efforts of US-related conspiracy theories posted online, with a WeChat search of “Coronavirus is from the U.S.” reported to mostly yield articles explaining why such claims are unreasonable.[143][j]

On 22 February, US officials alleged that Russia is behind an ongoing disinformation campaign, using thousands of social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to deliberately promote unfounded conspiracy theories, claiming the virus is a biological weapon manufactured by the CIA and the US is waging economic war on China using the virus.[156][12][157][k]

Reza Malekzadeh, deputy health minister, rejected bioterrorism theories.

According to Washington DC-based nonprofit Middle East Media Research Institute, numerous writers in the Arabic press have promoted the conspiracy theory that COVID-19, as well as SARS and the swine flu virus, were deliberately created and spread to sell vaccines against these diseases, and it is “part of an economic and psychological war waged by the U.S. against China with the aim of weakening it and presenting it as a backward country and a source of diseases”.[162][l]

The same theory has been reported via Iranian propaganda “to damage its culture and honor”.[163] Reza Malekzadeh, Iran’s deputy health minister and former Minister of Health, rejected claims that the virus was a biological weapon, pointing out that the US would be suffering heavily from it. He said Iran was hard-hit because its close ties to China and reluctance to cut air ties introduced the virus, and because early cases had been mistaken for influenza.[164][m] The theory has also circulated in the Philippines[n] and Venezuela.[o]

Jewish origin

In the Muslim world

Iran’s Press TV asserted that “Zionist elements developed a deadlier strain of coronavirus against Iran”.[14] Similarly, Arab media outlets accused Israel and the United States of creating and spreading COVID-19, avian flu, and SARS.[177] Users on social media offered other theories, including the allegation that Jews had manufactured COVID-19 to precipitate a global stock market collapse and thereby profit via insider trading,[178] while a guest on Turkish television posited a more ambitious scenario in which Jews and Zionists had created COVID-19, avian flu, and Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever to “design the world, seize countries, [and] neuter the world’s population”.[179]

Israeli attempts to develop a COVID-19 vaccine prompted negative reactions in Iran. Grand Ayatollah Naser Makarem Shirazi denied initial reports that he had ruled that a Zionist-made vaccine would be halal,[180] and one Press TV journalist tweeted that “I’d rather take my chances with the virus than consume an Israeli vaccine”.[181] A columnist for the Turkish Yeni Akit asserted that such a vaccine could be a ruse to carry out mass sterilization.[182]

In the United States

An alert by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation regarding the possible threat of far-right extremists intentionally spreading the coronavirus mentioned blame being assigned to Jews and Jewish leaders for causing the pandemic and several statewide shutdowns.[183]

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) published reports and blogs about online anti-Israel[184] and antisemitic conspiracy theories and misinformation concerning the origin of COVID-19, its spread, and the creation or profitability of vaccines, among other things, linking them to centuries-old antisemitic tropes, particularly in times of plague.[185][186][187] ADL also posted blogs holding large tech platforms such as Facebook responsible for the viral spread of these conspiracy theories; ADL blamed such platforms for their failure to adopt policies requiring the removal of this content, failure to enforce existing content moderation policies around hate speech, and/or failure to otherwise restrict the reach and amplification of this content.[188]

Anti-Muslim

In India, Muslims have been blamed for spreading infection following the emergence of cases linked to a Tablighi Jamaat religious gathering.[189] There are reports of vilification of Muslims on social media and attacks on individuals in India.[190] Claims have been made that Muslims are selling food contaminated with coronavirus and that a mosque in Patna was sheltering people from Italy and Iran.[191] These claims were shown to be false.[192] In the UK, there are reports of far-right groups blaming Muslims for the coronavirus outbreak and falsely claiming that mosques remained open after the national ban on large gatherings.[193] In the U.S., the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported on Islamophobic anti-Muslim bigotry connected with the coronavirus.[194]

Population-control scheme

According to the BBC, Jordan Sather, a conspiracy theorist YouTuber supporting the QAnon conspiracy theory and the anti-vax movement, has falsely claimed that the outbreak was a population-control scheme created by the Pirbright Institute in England and by former Microsoft CEO Bill Gates.[1][195][196]

Piers Corbyn during an interview on Good Morning Britain described the coronavirus as a “psychological operation to close down the economy in the interests of mega-corporations”.[197]

5G mobile phone networks

5G towers have been burned by people wrongly blaming them for COVID-19.

Openreach engineers appealed on anti-5G Facebook groups, saying they are not involved in mobile networks, and workplace abuse is making it difficult for them to maintain phonelines and broadband.

In February 2020, BBC News reported that conspiracy theorists on social media groups alleged a link between coronavirus and 5G mobile networks, claiming that the Wuhan and Diamond Princess outbreaks were directly caused by electromagnetic fields and by the introduction of 5G and wireless technologies. Conspiracy theorists have alleged that the coronavirus outbreak was a cover-up for a 5G-related illness[41].

In March 2020, Thomas Cowan, a holistic medical practitioner who trained as a physician and operates on probation with Medical Board of California, alleged that COVID-19 is caused by 5G, based on the claims that African countries were not affected significantly by the pandemic and Africa was not a 5G region.[198][199] Cowan also falsely alleged that the viruses were waste from cells that have been poisoned by electromagnetic fields, and that historical viral pandemics coincided with major developments in radio technology.[199] The video of his claims went viral and was recirculated by celebrities, including Woody Harrelson, John Cusack, and singer Keri Hilson.[200] The claims may also have been recirculated by an alleged “coordinated disinformation campaign”, similar to campaigns used by the Internet Research Agency in Saint Petersburg, Russia.[201] The claims were criticized on social media and debunked by Reuters,[202] USA Today,[203] Full Fact[204] and American Public Health Association executive director Georges C. Benjamin.[198][205]

Cowan’s claims were repeated by Mark Steele, a conspiracy theorist who claimed to have first hand knowledge that 5G was in fact a weapon system capable of causing symptoms identical to those produced by the virus.[206] Kate Shemirani, a former nurse who had been struck-off the UK nursing registry, and had become a promoter of conspiracy theories, repeatedly claimed that these symptoms were precisely the same as those produced by exposure to electromagnetic fields.[207]

Professor Steve Powis, national medical director of NHS England, described theories linking 5G mobile phone networks to COVID-19 as the “worst kind of fake news”.[208] Viruses cannot be transmitted by radio waves, and COVID-19 has spread and continues to spread in many countries that do not have 5G networks.[209] In fact, the health of citizens in the well-developed countries with 5G is better than that of citizens from lesser-developed, poorer countries without it.

After telecommunications masts in several parts of the United Kingdom were the subject of arson attacks, British Cabinet Office Minister Michael Gove said the theory that COVID-19 virus may be spread by 5G wireless communication is “just nonsense, dangerous nonsense as well”.[210] Vodafone announced that two Vodafone masts and two it shares with O2, another cellular provider, had been targeted.[211][212]

By 6 April 2020, at least 20 mobile phone masts in the UK had been vandalised since the previous Thursday.[213] Because of the slow rollout of 5G in the UK, many of the damaged masts had only 3G and 4G equipment.[213] Mobile phone and home broadband operators estimated there were at least 30 incidents of confronting engineers maintaining equipment in the week up to 6 April.[213] As of 30 May, there have been 29 incidents of attempted arson at mobile phone masts in the Netherlands, including one case where “Fuck 5G” was written.[214][215] There have been incidents in Ireland and Cyprus as well.[216] Facebook has deleted multiple messages encouraging attacks on 5G equipment.[213]

Engineers working for Openreach posted pleas on anti-5G Facebook groups asking to be spared abuse as they are not involved with maintaining mobile networks.[217] Mobile UK said the incidents were affecting attempts to maintain networks that support home working and provide critical connections to vulnerable customers, emergency services, and hospitals.[217] A widely circulated video shows people working for broadband company Community Fibre being abused by a woman who accuses them of installing 5G as part of a plan to kill the population.[217]

YouTube announced that it would reduce the amount of content claiming links between 5G and coronavirus.[211] Videos that are conspiratorial about 5G that do not mention coronavirus would not be removed, though they might be considered “borderline content”, removed from search recommendations and losing advertising revenue.[211] The discredited claims had been circulated by British conspiracy theorist David Icke in videos (subsequently removed) on YouTube and Vimeo, and an interview by London Live TV network, prompting calls for action by Ofcom.[218][219]

On 12 April 2020, Gardaí and fire services were called to fires at 5G masts in County Donegal, Ireland.[220][220] The Gardaí, although awaiting the results of tests, are treating the fires as arson.[220]

There were 20 suspected arson attacks on phone masts in the UK over the Easter, 2020, weekend.[208] These included an incident in Dagenham where three men were arrested on suspicion of arson, a fire in Huddersfield that affected a mast used by emergency services, and a fire in a mast that provides mobile connectivity to the NHS Nightingale Hospital Birmingham.[208]

Ofcom issued guidance to ITV following comments by Eamonn Holmes about 5G and coronavirus on This Morning.[221] Ofcom said the comments were “ambiguous” and “ill-judged” and they “risked undermining viewers’ trust in advice from public authorities and scientific evidence”.[221] Ofcom also found local channel London Live in breach of standards for an interview it had with David Icke. It said that he had “expressed views which had the potential to cause significant harm to viewers in London during the pandemic”.[221]

Some telecom engineers have reported threats of violence, including threats to stab and murder them, by individuals who believe them to be working on 5G networks.[222] West Midlands Police said the crimes in question are being taken very seriously.[222]

On 24 April 2020, The Guardian revealed that Jonathan Jones, an evangelical pastor from Luton, had provided the male voice on a recording blaming 5G for deaths caused by coronavirus.[223] He claimed to have formerly headed the largest business unit at Vodafone, but insiders at the company said that he was hired for a sales position in 2014 when 5G was not a priority for the company and that 5G would not have been part of his job.[223] He left the company after less than a year.[223]

Polio vaccine

Social media posts in Cameroon pushed a conspiracy theory that polio vaccines contained coronavirus, further complicating polio eradication beyond the logistical and funding difficulties created by the COVID-19 pandemic.[224]

Misreporting of morbidity and mortality numbers

Alleged leak of death toll

On 5 February, Taiwan News published an article claiming that Tencent had accidentally leaked the real numbers of death and infection in China. Taiwan News suggests the Tencent Epidemic Situation Tracker had briefly showed infected cases and death tolls many times higher of the official figure, citing a Facebook post by 38-year-old Taiwanese beverage store owner Hiroki Lo and an anonymous Taiwanese netizen.[225] The article, referenced by other news outlets such as the Daily Mail and widely circulated on Twitter, Facebook and 4chan, sparked a wide range of conspiracy theories that the screenshot indicates the real death toll instead of the ones published by health officials.[226] Justin Lessler, associate professor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, claims the numbers of the alleged “leak” are unreasonable and unrealistic, citing the case fatality rate as far lower than the ‘leaked information’. A spokesman for Tencent responded to the news article, claiming the image was doctored, and it features “false information which we never published”.[227]

Keoni Everington, author of the original news article, defended and asserted the authenticity of the leak.[226] Brian Hioe and Lars Wooster of New Bloom magazine debunked the theory from data on other websites, which were using Tencent’s database to generate custom visualizations while showing none of the inflated figures appearing in the images promulgated by Taiwan News. Thus, they concluded the screenshot was digitally fabricated.[226]

Misinformation against Taiwan

On 26 February 2020, the Taiwanese Central News Agency reported that large amounts of misinformation had appeared on Facebook claiming the pandemic in Taiwan was out of control, the Taiwanese government had covered up the total number of cases, and that President Tsai Ing-wen had been infected. The Taiwan fact-checking organization had suggested the misinformation on Facebook shared similarities with mainland China due to its use of simplified Chinese characters and mainland China vocabulary. The organization warned that the purpose of the misinformation is to attack the government.[228][229][230]

In March 2020, Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice Investigation Bureau warned that mainland China was trying to undermine trust in factual news by portraying the Taiwanese government reports as fake news. Taiwanese authorities have been ordered to use all possible means to track whether the messages were linked to instructions given by the Communist Party of China. The PRC’s Taiwan Affairs Office denied the claims, calling them lies, and said that Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party was “inciting hatred” between the two sides. They then claimed that the “DPP continues to politically manipulate the virus”.[231] According to The Washington Post, China has used organized disinformation campaigns against Taiwan for decades.[232]

Nick Monaco, the research director of the Digital Intelligence Lab at Institute for the Future, analyzed the posts and concluded that the majority appear to have come from ordinary users in China, not the state. However, he criticized the Chinese government’s decision to allow the information to spread beyond China’s Great Firewall, which he described as “malicious”.[233] According to Taiwan News, nearly one in four cases of misinformation are believed to be connected to China.[234]

On 27 March 2020, the American Institute in Taiwan announced that it was partnering with the Taiwan FactCheck Center to help combat misinformation about the COVID-19 outbreak.[235]

Misrepresented World Population Project map

In early February, a decade-old map illustrating a hypothetical viral outbreak published by the World Population Project (part of the University of Southampton) was misappropriated by a number of Australian media news outlets (and British tabloids The Sun, Daily Mail and Metro)[236] which claimed the map represented the 2020 coronavirus outbreak. This misinformation was then spread via the social media accounts of the same media outlets, and while some outlets later removed the map, the BBC reported that a number of news sites had yet to retract the map.[236]

Nurse whistleblower

On 24 January, a video circulated online appearing to be of a nurse named Jin Hui[237] in Hubei, describing a far more dire situation in Wuhan than reported by Chinese officials. The video claimed that more than 90,000 people had been infected with the virus in China, that the virus could spread from one person to 14 people (R0=14) and that the virus was starting a second mutation.[238] The video attracted millions of views on various social media platforms and was mentioned in numerous online reports. However, the BBC noted that, contrary to its English subtitles in one of the video’s existing versions, the woman does not claim to be either a nurse or a doctor in the video and that her suit and mask do not match the ones worn by medical staff in Hubei.[1] The claimed R0 of 14 in the video was noted by the BBC to be inconsistent with the expert estimation of 1.4 to 2.5 at that time.[239] The video’s claim of 90,000 infected cases is noted to be ‘unsubstantiated’.[1][238]

Decline in cellphone subscriptions

There was a decrease of nearly 21 million cellphone subscriptions among the three largest cellphone carriers in China, which led to misinformation that this is evidence for millions of deaths due to the coronavirus in China.[240] The drop is attributed to cancellations of phone services due to a downturn in the social and economic life during the outbreak.[240]

Disease spread

California herd immunity in 2019

On 31 March 2020, Victor Davis Hanson publicized a theory that COVID-19 may have been in California in the fall of 2019 resulting in a level of herd immunity to at least partially explain differences in infection rates in cities such as New York City vs Los Angeles.[241] Dr. Jeff Smith of Santa Clara County stated that evidence indicated the virus may have been in California since December 2019.[242] Early genetic and antibody analyses refute the idea that the virus was in the United States prior to January 2020.[243][244][245][246]

Patient Zero

In March, conspiracy theorists started the false rumor that Maatje Benassi, a U.S. army reservist, was “Patient Zero” of the pandemic, the first person to be infected with coronavirus. Benassi was targeted because of her participation in the 2019 Military World Games before the pandemic started, even though she never actually tested positive for the virus. Conspiracy theorists even connected her family to the DJ Benny Benassi as a Benassi virus plot, even though Ben has no relation to Maatje and also never had the virus.[247]

Resistance/susceptibility based on ethnicity

There have been claims that specific ethnicities are more or less vulnerable to COVID-19. COVID-19 is a new zoonotic disease, so no population has yet had the time to develop population immunity.[medical citation needed]

Beginning on 11 February, reports, quickly spread via Facebook, implied that a Cameroonian student in China had been completely cured of the virus due to his African genetics. While a student was successfully treated, other media sources have noted that no evidence implies Africans are more resistant to the virus and labeled such claims as false information.[248] Kenyan Secretary of Health Mutahi Kagwe explicitly refuted rumors that “those with black skin cannot get coronavirus”, while announcing Kenya’s first case on 13 March.[249] This myth was cited as a contributing factor in the disproportionately high rates of infection and death observed among African Americans.[250][251]

There have been claims of “Indian immunity”: that the people of India have more immunity to the COVID-19 virus due to living conditions in India. This idea was deemed “absolute drivel” by Anand Krishnan, professor at the Centre for Community Medicine of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). He said there was no population immunity to the COVID-19 virus yet, as it is new, and it is not even clear whether people who have recovered from COVID-19 will have lasting immunity, as this happens with some viruses but not with others.[252]

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei claimed the virus was genetically targeted at Iranians by the US, and this is why it is seriously affecting Iran. He did not offer any evidence.[253][28]

Xenophobic blaming by ethnicity and religion

Play media

Play mediaUN video warns that misinformation against groups may lower testing rates and increase transmission.

COVID-19-related xenophobic attacks have been made against individuals with the attacker blaming the victim for COVID-19 on the basis of his or her ethnicity. People who are considered to look Chinese have been subjected to COVID-19-related verbal and physical attacks in many other countries, often by people accusing them of transmitting the virus.[254][255][256] Within China, there has been discrimination (such as evictions and refusal of service in shops) against people from anywhere closer to Wuhan (where the pandemic started) and against anyone perceived as being non-Chinese (especially those considered African), as the Chinese government has blamed continuing cases on re-introductions of the virus from abroad (90% of reintroduced cases were by Chinese passport-holders). Neighbouring countries have also discriminated against people seen as Westerners.[257][258][259] People have also simply blamed other local groups along the lines of pre-existing social tensions and divisions, sometimes citing reporting of COVID-19 cases within that group. For instance, Muslims have been widely blamed, shunned, and discriminated against in India (including some violent attacks), amid unfounded claims that Muslims are deliberately spreading COVID-19, and a Muslim event at which the disease did spread has received far more public attention than many similar events run by other groups and the government.[260] White supremacist groups have blamed COVID-19 on non-whites and advocated deliberately infecting minorities they dislike, such as Jews.[261]

Bat soup consumption

Some media outlets, including Daily Mail and RT, as well as individuals, disseminated a video showing a Chinese woman eating a bat, falsely suggesting it was filmed in Wuhan and connecting it to the outbreak.[262][263] However, the widely circulated video contains unrelated footage of a Chinese travel vlogger, Wang Mengyun, eating bat soup in the island country of Palau in 2016.[262][263][264][265] Wang posted an apology on Weibo,[264][265] in which she said she had been abused and threatened,[264] and that she had only wanted to showcase Palauan cuisine.[264][265] The spread of misinformation about bat consumption has been characterized by xenophobic and racist sentiment toward Asians.[113][266][267] In contrast, scientists suggest the virus originated in bats and migrated into an intermediary host animal before infecting people.[113][268]

Large gatherings

South Korean “conservative populist” Jun Kwang-hun told his followers there was no risk to mass public gatherings as the virus was impossible to contract outdoors. Many of his followers are elderly.[269]

Lifetime of the virus

Misinformation has spread that the lifetime of SARS-CoV-2 is only 12 hours and that staying home for 14 hours during Janata curfew would break the chain of transmission.[270] Another message claimed that observing Janata curfew would result in the reduction of COVID-19 cases by 40%.[270]

Mosquitoes

It has been claimed that mosquitoes transmit coronavirus. There is no evidence that this is true; coronavirus spreads through small droplets of saliva and mucus.[209]

Objects

A fake Costco product recall notice circulated on social media purporting that Kirkland-brand bath tissue had been contaminated with COVID-19 (meaning SARS-CoV-2) due to the item being made in China. No evidence supports that SARS-CoV-2 can survive on surfaces for prolonged periods of time (as might happen during shipping), and Costco has not issued such a recall.[271][272][273]

A warning claiming to be from the Australia Department of Health said coronavirus spreads through petrol pumps and that everyone should wear gloves when filling up petrol in their cars.[274]

There were claims that wearing shoes at one’s home was the reason behind the spread of the coronavirus in Italy.[275]

Cruise ships’ safety from infection

Claims by cruise-ship operators notwithstanding, there are many cases of coronaviruses in hot climates; some countries in the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, and the Persian Gulf are severely affected.

In March 2020, the Miami New Times reported that managers at Norwegian Cruise Line had prepared a set of responses intended to convince wary customers to book cruises, including “blatantly false” claims that the coronavirus “can only survive in cold temperatures, so the Caribbean is a fantastic choice for your next cruise”, that “[s]cientists and medical professionals have confirmed that the warm weather of the spring will be the end of the [c]oronavirus”, and that the virus “cannot live in the amazingly warm and tropical temperatures that your cruise will be sailing to”.[276]

Flu is seasonal (becoming less frequent in the summer) in some countries, but not in others. While it is possible that the COVID-19 coronavirus will also show some seasonality, it is not yet known.[277][278][279][medical citation needed] The COVID-19 coronavirus spread along international air travel routes, including to tropical locations.[280] Outbreaks on cruise ships, where an older population lives in close quarters, frequently touching surfaces which others have touched, were common.[281][282]

It seems that COVID-19 can be transmitted in all climates.[209] It has seriously affected many warm-climate countries. For instance, Dubai, with a year-round average daily high of 28.0 Celsius (82.3 °F) and the airport said to have the world’s most international traffic, has had thousands of cases.

Prevention

Efficacy of hand sanitizer, “antibacterial” soaps

Washing in soap and water for at least 20 seconds is the best way to clean hands. The second-best is a hand sanitizer that is at least 60% alcohol.[283]

Claims that hand sanitizer is merely “antibacterial not antiviral”, and therefore ineffective against COVID-19, have spread widely on Twitter and other social networks. While the effectiveness of sanitiser depends on the specific ingredients, most hand sanitiser sold commercially inactivates SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19.[284][285] Hand sanitizer is recommended against COVID-19,[209] though unlike soap, it is not effective against all types of germs.[286] Washing in soap and water for at least 20 seconds is recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) as the best way to clean hands in most situations. However, if soap and water are not available, a hand sanitizer that is at least 60% alcohol can be used instead, unless hands are visibly dirty or greasy.[283][287] The CDC and the Food and Drug Administration both recommend plain soap; there is no evidence that “antibacterial soaps” are any better, and limited evidence that they might be worse long-term.[288][289]

Public use of face masks

The U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams urged people to wear face masks and acknowledged that it’s difficult to correct earlier messaging that masks do not work for the general public.[290]

Although authorities, especially in Asia, recommended wearing face masks in public, in other parts of the world conflicting advice caused confusion among the general population.[291] Several governments and institutions, such as in the United States, initially dismissed the use of face masks by the general population, often with misleading or incomplete information about their effectiveness.[292][293][294] Commentators have attributed the anti-mask messaging to efforts to manage the mask shortages, as governments did not act quickly enough, remarking that the claims go beyond the science or were simply lies.[294][295][296][297]

In February 2020, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams tweeted “Seriously people- STOP BUYING MASKS! They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!”[298], but he later reversed his position with evidence mounting that masks can limit the spread of coronavirus.[299][300] On 12 June 2020, Anthony Fauci, a key member of the White House coronavirus task force, confirmed that the American public were not told to wear masks from the beginning due to the shortage of masks and explained that masks do actually work.[301][302][303][304][305]

Some media outlets claimed that neck gaiters were worse than not wearing masks at all in the COVID-19 pandemic, misinterpreting a study which was intended to demonstrate a method for evaluating masks (and not actually to determine the effectiveness of different types of masks).[306][307][308] The study also only looked at one wearer wearing the one neck gaiter made from a polyester/spandex blend, which is not sufficient evidence to support the claim about gaiters made in the media.[307] The study found that the neck gaiter, which was made from a thin and stretchy material, appeared to be ineffective at limiting airborne droplets expelled from the wearer; Isaac Henrion, one of the co-authors, suggests that the result was likely due to the material rather than the style, stating that “Any mask made from that fabric would probably have the same result, no matter the design.”[309] Warren S. Warren, a co-author, said that they tried to be careful with their language in interviews, but added that the press coverage has “careened out of control” for a study testing a measuring technique.[306]

There are false claims spread that mask wearers will suffer from lower oxygen or higher carbon dioxide levels in the blood.[310][311] Another false claim spread is that masks harm or weaken the immune system.[312]

Anti-maskers have called upon bogus claims about legal or medical exemptions in their refusal to mask.[313] They have, for instance, claimed that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA; designed to prohibit discrimination based on disabilities) allows exemption from mask requirements, but the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) responded by stating that the act “does not provide a blanket exemption to people with disabilities from complying with legitimate safety requirements necessary for safe operations.”[314] The DOJ has issued a warning about cards (some featuring DOJ logos and notices about ADA) that “exempt” its holder from wearing a mask, stating that they are fraudulent and were not issued by a government agency.[315][316]

On 31 July 2020, Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte said those who didn’t have cleaning supplies could use gasoline as a disinfectant to clean their masks.[317] He further stated that “For people who don’t [have Lysol], drench it in gasoline or diesel… just find some gasoline [and] dip your hand [with the mask] in it.”[317] His spokesman Harry Roque later corrected him.[317]

Alcohol (ethanol and poisonous methanol)

Contrary to some reports, drinking alcohol does not protect against COVID-19, and can increase health risks[209] (short term and long term). Drinking alcohol is ethanol; other alcohols, such as methanol, which causes methanol poisoning, are acutely poisonous, and may be present in badly prepared alcoholic beverages.[318]

Iran has reported incidents of methanol poisoning, caused by the false belief that drinking alcohol would cure or protect against coronavirus;[319] alcohol is banned in Iran, and bootleg alcohol may contain methanol.[320] According to Iranian media in March 2020, nearly 300 people have died and more than a thousand have become ill due to methanol poisoning, while Associated Press gave figures of around 480 deaths with 2,850 others affected.[321] The number of deaths due to methanol poisoning in Iran reached over 700 by April.[322] Iranian social media had circulated a story from British tabloids that a British man and others had been cured of coronavirus with whiskey and honey,[319][323] which combined with the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers as disinfectants, led to the false belief that drinking high-proof alcohol can kill the virus.[319][320][321]

Similar incidents have occurred in Turkey, with 30 Turkmenistan citizens dying from methanol poisoning related to coronavirus cure claims.[324][325]

In Kenya, the Governor of Nairobi Mike Sonko has come under scrutiny for including small bottles of the cognac Hennessy in care packages, falsely claiming that alcohol serves as “throat sanitizer” and that, from research, it is believed that “alcohol plays a major role in killing the coronavirus.”[326][327]

Vegetarian immunity

Claims that vegetarians are immune to coronavirus spread online in India, causing “#NoMeat_NoCoronaVirus” to trend on Twitter.[328][better source needed] Eating meat does not have an effect on COVID-19 spread, except for people near where animals are slaughtered, said Anand Krishnan.[329] Fisheries, Dairying and Animal Husbandry Minister Giriraj Singh said the rumour had significantly affected industry, with the price of a chicken falling to a third of pre-pandemic levels. He also described efforts to improve the hygiene of the meat supply chain.[330]

Religious protection

A number of religious groups have claimed protection due to their faith, some refusing to stop large religious gatherings. In Israel, some Ultra-Orthodox Jews initially refused to close synagogues and religious seminaries and disregarded government restrictions because “The Torah protects and saves”,[331] which resulted in an eight-fold faster rate of infection among some groups.[332] The Islamic missionary movement Tablighi Jamaat organised Ijtema mass gatherings in Malaysia, India, and Pakistan whose participants believed that God will protect them, causing the biggest rise in COVID-19 cases in these and other countries.[333][36][334] In Iran, the head of Fatima Masumeh Shrine encouraged pilgrims to visit the shrine despite calls to close the shrine, saying that they “consider this holy shrine to be a place of healing.”[335] In South Korea the River of Grace Community Church in Gyeonggi Province spread the virus after spraying salt water into their members’ mouths in the belief that it would kill the virus,[336] while the Shincheonji Church of Jesus in Daegu where a church leader claimed that no Shincheonji worshipers had caught the virus in February while hundreds died in Wuhan, later caused in the biggest spread of the virus in the country.[337][338]

In Tanzania, President John Magufuli, instead of banning congregations, urged the faithfuls to go to pray in churches and mosques in the belief that it will protect them. He said that the coronavirus is a devil, therefore “cannot survive in the body of Jesus Christ, it will burn” (the “body of Jesus Christ” refers to the church).[339][340]

In Somalia, myths have spread claiming Muslims are immune to the virus.[341]

Despite the coronavirus outbreak, on 9 March, the Church of Greece announced that Holy Communion, in which churchgoers eat pieces of bread soaked in wine from the same chalice, would continue as a practice.[342] The Holy Synod said Holy Communion “cannot be the cause of the spread of illness”, with Metropolitan Seraphim saying the wine was without blemish because it represented the blood and body of Christ, and that “whoever attends Holy Communion is approaching God, who has the power to heal.”[342] The Church refused to restrict Christians from taking Holy Communion,[343] which was supported by several clerics,[344] some politicians, and health professionals.[344][345] The Greek Association of Hospital Doctors criticized these professionals for putting their religious beliefs before science.[344]

Cocaine

Cocaine does not protect against COVID-19. Several viral tweets purporting that snorting cocaine would sterilize one’s nostrils of the coronavirus spread around Europe and Africa. In response, the French Ministry of Health released a public service announcement debunking this claim, saying “No, cocaine does NOT protect against COVID-19. It is an addictive drug that causes serious side effects and is harmful to people’s health.” The World Health Organisation also debunked the claim.[346]

Helicopter spraying

In some Asian countries, it has been claimed that one should stay at home on particular days when helicopters spray “COVID–19 disinfectant” over homes. No such spraying has taken place, nor is it planned, nor, as of July 2020, is there any such agent to be sprayed.[347][348]

Vibrations

The notion that the vibrations generated by clapping together during Janata curfew will kill the virus was debunked by the media.[349] Amitabh Bachchan was heavily criticised for one of his tweets, which claimed vibrations from clapping, blowing conch shells as part of Sunday’s Janata Curfew would have reduced or destroyed coronavirus potency as it was Amavasya, the darkest day of the month.[350]

Food

In India, fake news circulated that the World Health Organization warned against eating cabbage to prevent coronavirus infection.[351] Claims that the poisonous fruit of the Datura plant is a preventive measure for COVID-19 resulted in eleven people being hospitalized in India. They ate the fruit, following the instructions from a TikTok video that propagated misinformation regarding the prevention of COVID-19.[352][353]

Treatment misinformation

Widely circulated posts on social media have made many unfounded claims of methods against coronavirus. Some of these claims are scams, and some promoted methods are dangerous and unhealthy.[209][354]

Hospital conditions

Some conservative figures in the United States, such as Richard Epstein,[355] downplayed the scale of the pandemic, saying it has been exaggerated as part of an effort to hurt President Trump. Some people pointed to empty hospital parking lots as evidence that the virus has been exaggerated. Despite the empty parking lots, many hospitals in New York City and other places experienced thousands of COVID-19-related hospitalizations.[356]

Herbal treatments

Various national and party-held Chinese media heavily advertised an “overnight research” report by Wuhan Institute of Virology and Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences, on how shuanghuanglian, an herb mixture from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), can effectively inhibit the novel coronavirus. The report led to a purchase craze of shuanghuanglian.[357]

The president of Madagascar Andry Rajoelina launched and promoted in April 2020 a herbal drink based on an artemisia plant as a miracle cure that can treat and prevent COVID-19 despite a lack of medical evidence. The drink has been exported to other African countries.[35][358]

Vitamin D

Claims that Vitamin D pills could help prevent the coronavirus circulated on social media in Thailand.[359] The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, while noting that “current advice is that the whole population of the UK should take vitamin D supplements to prevent vitamin D deficiency”, found “no clinical evidence that vitamin D supplements are beneficial in preventing or treating COVID-19”.[360] Vitamin D deficiency, however, raises the risk of a Covid 19 infection, as well as the severity of the infection.[361]

Common cold and flu treatments

There were also claims that a 30-year-old Indian textbook lists aspirin, antihistamines, and nasal spray as treatments for COVID-19. The textbook actually talks about coronaviruses in general, as a family of viruses.[362]

A rumor circulated on social media posts on Weibo, Facebook and Twitter claiming that Chinese experts said saline solutions could kill the coronavirus. There is no evidence that saline solutions have such an effect.[363]

A tweet from French health minister Olivier Véran, a bulletin from the French health ministry, and a small speculative study in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine raised concerns about ibuprofen worsening COVID-19, which spread extensively on social media. The European Medicines Agency[364] and the World Health Organization recommended COVID-19 patients keep taking ibuprofen as directed, citing lack of convincing evidence of any danger.[365]

Animal-based products or foods

Indian political activist Swami Chakrapani and Member of the Legislative Assembly Suman Haripriya claimed that drinking cow urine and applying cow dung on the body can cure COVID-19.[366][367] WHO’s chief scientist Soumya Swaminathan criticised politicians incautiously spreading such misinformation without an evidence base.[368]

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) prescriptions

Since its third version, the COVID management guidelines from the Chinese National Health Commission recommends using Traditional Chinese Medicines to treat the disease.[369] In Wuhan, the local authorities have pushed for a set of TCM prescriptions to be used for every case since early February.[370] One formula was promoted at the national level by mid-February.[371] The local field hospitals were explicitly TCM-oriented. According to state-owned media, as of 16 March 2020, 91.91% of all Hubei patients have used TCM, with the rate reaching 99% in field hospitals and 94% in bulk quarantine areas.[372]

Chloroquine

There were claims that chloroquine was used to cure more than 12,000 COVID-19 patients in Nigeria.[373]

Hydroxychloroquine

On 11 March, Adrian Bye, a tech startup leader who is not a doctor, suggested to cryptocurrency investors Gregory Rigano and James Todaro that “chloroquine will keep most people out of hospital.” (Bye later admitted that he had reached this conclusion through “philosophy” rather than medical research.) Two days later, Rigano and Todaro promoted chloroquine in a self-published article that falsely claimed affiliation with three institutions. Google removed the article.[374]

Dangerous treatments

Some QAnon proponents, including Jordan Sather and others, have promoted gargling “Miracle Mineral Supplement” (actually chlorine dioxide, a chemical used in some industrial applications as a bleach that may cause life-threatening reactions and even death) as a way of preventing or curing the disease. The Food and Drug Administration has warned multiple times that drinking MMS is “dangerous” as it may cause “severe vomiting” and “acute liver failure”.[375]

Untested treatments

In February 2020, televangelist Jim Bakker promoted a colloidal silver solution, sold on his website, as a remedy for coronavirus COVID-19; naturopath Sherrill Sellman, a guest on his show, falsely stated that it “hasn’t been tested on this strain of the coronavirus, but it’s been tested on other strains of the coronavirus and has been able to eliminate it within 12 hours.”[376] The US Food and Drug Administration and New York Attorney General’s office both issued cease-and-desist orders against Bakker, and he was sued by the state of Missouri over the sales.[377][378]

The New York Attorney General’s office also issued a cease-and-desist order to radio host Alex Jones, who was selling silver-infused toothpaste that he falsely claimed could kill the virus and had been verified by federal officials,[379] causing a Jones spokesman to deny the products had been sold for the purpose of treating any disease.[33] The FDA would later threaten Jones with legal action and seizure of several silver-based products if he continued to promote their use against coronavirus.[380]

Misinformation that the government is spreading an “anti-corona” drug in the country during Janata curfew, a stay-at-home curfew enforced in India, went viral on social media.[381] The yoga guru Ramdev claimed that one can treat coronavirus by pouring mustard oil through the nose, causing the virus to flow into the stomach where it would be destroyed by gastric acid. He also claimed that if a person holds his breath for a minute, it means s/he is not suffering from any type of coronavirus, symptomatic or asymtomatic. Both these claims were found to be false.[382][383]

Following the first reported case of COVID-19 in Nigeria on 28 February, untested cures and treatments began to spread via platforms such as WhatsApp.[384]

The US Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested actor Keith Lawrence Middlebrook for selling a fake COVID-19 cure.[385]

Non-existent COVID-19 vaccine

Multiple social media posts have promoted a conspiracy theory claiming the virus was known and that a vaccine was already available. PolitiFact and FactCheck.org noted that no vaccine currently exists for COVID-19. The patents cited by various social media posts reference existing patents for genetic sequences and vaccines for other strains of coronavirus such as the SARS coronavirus.[386][4] The WHO reported that as of 5 February 2020, despite news reports of “breakthrough drugs” being discovered, there were no treatments known to be effective;[387] this included antibiotics and herbal remedies not being useful.[388]

On Facebook, a widely shared post claimed that seven Senegalese children had died because they had received a COVID-19 vaccine. No such vaccine exists, although some are in clinical trials.[389]

Spiritual healing

Another televangelist, Kenneth Copeland, claimed on Victory Channel during a programme called “Standing Against Coronavirus”, that he can cure television viewers of COVID-19 directly from the TV studio. The viewers had to touch the television screen to receive the spiritual healing.[390][391]

Recovery

It has been wrongly claimed that anyone infected with COVID-19 will have the virus in their bodies for life. While there is no curative treatment, infected individuals can recover from the disease, eliminating the virus from their bodies; getting supportive medical care early can help.[209]

Other

Name of the disease

Social media posts and internet memes claimed that COVID-19 derives from “Chinese Originated Viral Infectious Disease 19”, or similar, as supposedly the “19th virus to come out of China”.[392] In fact, the WHO named the disease as follows: CO stands for corona, VI for virus, D for disease and 19 for when the outbreak was first identified (31 December 2019).[393]

Simpsons prediction

Claims that The Simpsons had predicted the COVID-19 pandemic in 1993, accompanied by a doctored screenshot from the show (where the text “Corona Virus” was layered over the original text “Apocalypse Meow”, without blocking it from view), were later found to be false; the claim was widely spread on social media.[394][395]

United Kingdom £20 banknote

A tweet started an internet meme that Bank of England £20 banknotes contained a picture of a 5G mast and the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Facebook and YouTube removed items pushing this story, and fact checking organisations established that the picture is of Margate Lighthouse and the “virus” is the staircase at the Tate Britain.[396][397][398]

Hospital ship attack

The hospital ship USNS Mercy (T-AH-19) deployed to the Port of Los Angeles to provide backup hospital services for the region. On 31 March 2020, a Pacific Harbor Line freight train was deliberately derailed by its onboard engineer in an attempt to crash into the ship, but the attack was unsuccessful and no one was injured.[399][400] According to federal prosecutors, the train’s engineer “was suspicious of the Mercy, believing it had an alternate purpose related to COVID-19 or a government takeover”.[401]

Return of wildlife

During the pandemic, many false and misleading images or news reports about the environmental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic were shared by clickbait journalism sources and social media.[402]

A viral post that originated on Weibo and spread on Twitter claimed that a pack of elephants descended on a village under quarantine in China’s Yunnan, got drunk on corn wine, and passed out in a tea garden.[403] A Chinese news report debunked the claim that the elephants got drunk on corn wine and noted that wild elephants were a common sight in the village; the image attached to the post was originally taken at the Asian Elephant Research Center in Yunnan in December 2019.[402]

Following reports of reduced pollution levels in Italy as a result of lockdowns, images purporting to show swans and dolphins swimming in Venice canals went viral on social media. The image of the swans was revealed to have been taken in Burano, where swans are common, while footage of the dolphins was filmed at a port in Sardinia hundreds of miles away.[402] The Venice mayor’s office clarified that the reported water clarity in the canals was due to the lack of sediment being kicked up by boat traffic, not a reduction in water pollution as initially reported.[404]

Following the lockdown of India, a video clip purporting to show the extremely rare Malabar civet (a critically endangered, possibly extinct, species) walking the empty streets of Meppayur went viral on social media. Experts later identified the civet in the video as actually being the much commoner small Indian civet.[405] Another viral Indian video clip showed a pod of humpback whales allegedly returning to the Arabian Sea offshore from Mumbai following the shutdown of shipping routes; however, this video was found to have actually been taken in 2019 in the Java Sea.[406]

Government

Argentina

Argentinian president Alberto Fernández

Argentinian president Alberto Fernández and health minister Ginés García have been accused of spreading misinformation related to COVID-19 multiple times.

In a radio interview Fernández recommended drinking warm drinks since “heat kills the virus”. Scientific studies proved that this information is false. Fernández, in response to criticism, later said: “It’s a virus that, according to all medical reports in the world, dies at 26ºC. Argentina was in a climatic scenario where temperature was around 30ºC so it would be hard for the virus to survive.” He later added: “The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends us to drink warm drinks since heat kills the virus”; however, the WHO did not recommend that at all.[407]

On 23 January 2020, García claimed that “there is no chance that COVID-19 will exist in the country”.[408][409][410] This ended up being untrue, as the virus ended up reaching Argentina and lockdown was imposed in March.[411][412] González later apologized, saying: “I didn’t think it would reach our country so fast, it surprised us”.[413]

Fernández, González and other government officials have predicted that a peak in cases would occur in April, later May, then June, July and finally August.[414][415][416][417]

Brazil

Brazilian president

Jair Bolsonaro

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro openly attempted to force state and municipal governments to revoke social isolation measures they had begun by launching an anti lockdown campaign called “o Brasil não pode parar” (Brazil can’t stop). It received massive backlash both from the media and from the public, and was blocked by the supreme court justice.[418][419]