Is Facebook Bad for Society? New Insights on the Company’s Approach Raise Important Questions

Is Facebook a positive or negative influence on society – and does the company, or indeed anybody in a position to enact any type of change, actually care either way?

This question has been posed by many research reports and academic analyses over the years, but seemingly, the broader populous, at least in Western nations, really hadn’t give it a lot of consideration until the 2016 US Presidential Election, when it was revealed, in the aftermath, that foreign operatives, political activists and other groups had been using Facebook ads, posts and groups to influence US voter activity.

Suddenly, many realized that they may well have been manipulated, and while The Social Network has now implemented many more safeguards and detection measures to combat ‘coordinated inauthentic behavior’ by such groups, the concern is that this may not be enough, and it could be too late to stop the dangerous impact that Facebook has had, and is having, on society overall.

Facebook’s original motto of ‘move fast and break things‘ could, indeed, break society as we know it. That may seem alarmist, but the evidence is becoming increasingly clear.

Moving Fast

The launch of Facebook’s News Feed in September 2006 was a landmark moment for social media, providing a new way for people to engage with social platforms, and eventually, for the platforms themselves to better facilitate user engagement by highlighting the posts of most interest to users.

At that time, Facebook was only just starting to gain momentum, with 12 million total users, though that was already more than double its total audience count from the previous year. Facebook was also slowly consuming the audience of previous social media leader MySpace, and by 2007, with 20 million users, Facebook was already working on the next stage, and how it could keep people more engaged and glued to its app.

It introduced the Like button in 2007, which gave users a more implicit means to indicate their interest in a post or Page, and then in 2009, it rolled out the News Feed algorithm, which took into account various user behaviors and used them to define the order in which posts would appear in each individual’s feed – which, again, focused on making the platform more addictive, and more compelling.

And it worked – Facebook usage continued to rise, and on-platform engagement skyrocketed, and by the end of 2009, Facebook had more than 350 million total users. It almost doubled that again by the end of 2010, while it hit a billion total users in 2012. Clearly, the algorithm approach was working as intended – but again, in reference to Facebook’s creed at the time, while it was moving fast, it was almost certainly already breaking things in the process.

Though what, exactly, was being broken was not clear at that stage.

This week, in a statement to a House Commerce subcommittee hearing on how social media platforms contribute to the mainstreaming of extremist and radicalizing content, former Facebook director of monetization Tim Kendall has criticized the tactics that the company used within its growth process, and continues to employ today, which essentially put massive emphasis on maximizing user engagement, and largely ignore the potential consequences of that approach.

As per Kendall (via Ars Technica):

“The social media services that I and others have built over the past 15 years have served to tear people apart with alarming speed and intensity. At the very least, we have eroded our collective understanding – at worst, I fear we are pushing ourselves to the brink of a civil war.”

Which seems alarmist, right? How could a couple of Likes on Facebook lead us to the brink of civil war?

But that reality could actually be closer than many expect – for example, this week, US President Donald Trump has once again reiterated that he cannot guarantee a peaceful transfer of power in the event of him losing the November election. Trump says that because the polling process is flawed, he can’t say that he’ll respect the final decision – though various investigations have debunked Trump’s claims that mail-in ballots are riddled with fraud and will be used by his opponents to rig the final result.

Trump’s stance, in itself, is not overly surprising, but the concern now is that he could use his massive social media presence to mobilize his passionate supporter base in order to fight back against this perceived fraud if he disagrees with the result.

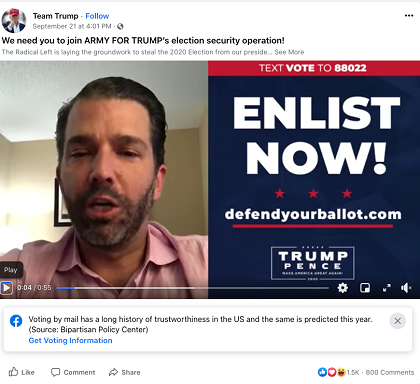

Indeed, this week, Trump’s son Don Jnr has been calling on Trump supporters to mobilize an ‘army’ to protect the election, which many see as a call to arms, and potential violence, designed to intimidate voters.

Note where this has been posted – while President Trump has a massive social media following across all the major platforms, Facebook is where he has seen the most success in connecting with his supporters and igniting their passions, by focusing on key pain points and divisive topics in order to reinforce support for the Republican agenda among voter groups.

Why does that seemingly resonate more on Facebook than other platforms?

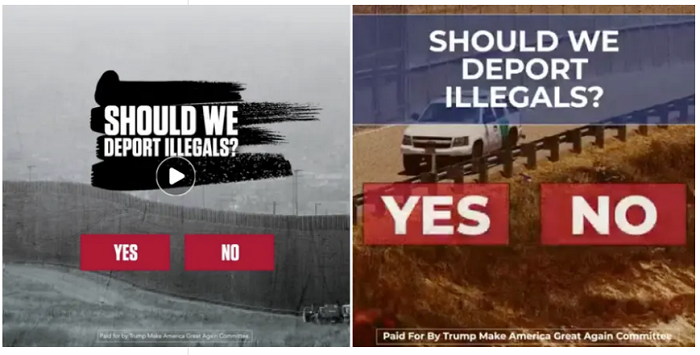

Because Facebook prioritizes engagement over all else, and posts that generate a lot of comments and discussion get more traction, and thereby get more distribution via Facebook’s algorithm. Facebook also offers complex ad targeting options which have enabled the Trump campaign to hone in on specific pain points and concerns for each group.

By using custom audiences, the Trump campaign is able to press on the key issues of concern to each specific audience subset, more effectively than it can on other platforms, which then exacerbates specific fears and prompts support for the Trump agenda.

How you view that approach comes down to your individual perspective, but the net result is that Facebook essentially facilitates more division and angst by amplifying and reinforcing such through its News Feed distribution. Because it focuses on engagement, and keeping users on Facebook – and the way to do that, evidently, is by highlighting debate and sparking discussion, no matter how healthy or not the subsequent interaction may be.

It’s clearly proven to be an effective approach for Facebook over time, and now also the Trump campaign. But it could also, as noted by Kendall, lead to something far worse as a result.

Civil Unrest

But it’s not just in the US that this has happened, and the Trump campaign is not the first to utilize Facebook’s systems in this way.

For example, in Myanmar back in 2014, a post circulated on Facebook which falsely accused a Mandalay business owner of raping a female employee. That post lead to the gathering of a mob, which eventually lead to civil unrest. The original accusation in this instance was incorrect, but Facebook’s vast distribution in the region enabled it to grow quickly, beyond the control of authorities.

In regions like Myanmar, which are still catching up with the western world in technical capacity, Facebook has become a key connector, an essential tool for distributing information and keeping people up to date. But the capability for anyone to have their say, on anything, can lead to negative impacts – with news and information coming from unofficial, unverified sources, messages can be misconstrued, misunderstood, and untrue claims are able to gain massive traction, without proper checks and balances in place.

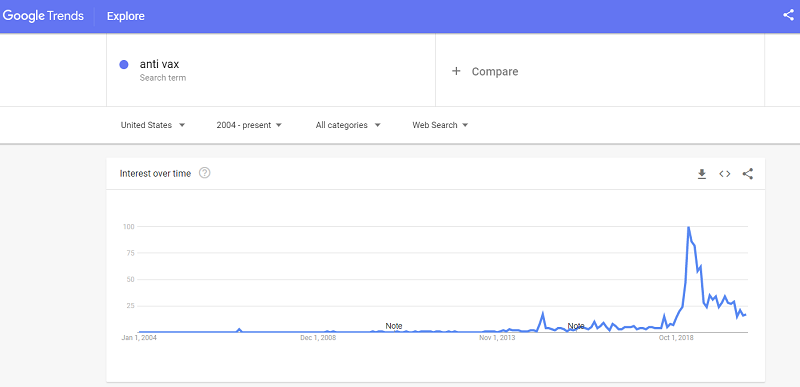

We’ve seen similar in the growth of pseudoscience and conspiracy theories in western regions – the growth of the anti-vax movement, for example, is largely attributed to Facebook distribution.

As you can see in this chart, using Google Trends data, searches for ‘anti-vax’ have gained significant momentum over the last decade, and while some of that is attributable to the terms used (people may not have always referred to ‘anti-vax’), it is clear that this counter-science movement has gained significant traction in line with the rise of The Social Network.

Is that coincidence, or could it be that by allowing everyone to have such huge potential reach with their comments, Facebook has effectively amplified the anti-vax movement, and others, because the debate around such sparks conversation and prompts debate?

That, essentially, is what’s Facebook’s News Feed is built upon, maximizing the distribution of on-platform discussions that trigger engagement.

As further explained by Kendall:

“We initially used engagement as sort of a proxy for user benefit, but we also started to realize that engagement could also mean [users] were sufficiently sucked in that they couldn’t work in their own best long-term interest to get off the platform. We started to see real-life consequences, but they weren’t given much weight. Engagement always won, it always trumped.”

Again, Facebook’s race to maximize engagement may indeed have lead to things being broken, but various reports from insiders suggest Facebook didn’t consider those expanded consequences.

And why would it? Facebook was succeeding, making money, building a massive empire. And it also, seemingly, gives people what they want. Some would argue that this is the right approach – adults should be free to decide what they read, what they engage with, and if that happens to be news and information that runs counter to the ‘official narrative’, then so be it.

Which is fine, so long as there are no major consequences. Like, say, the need to be vaccinated to stop the spread of a global pandemic.

Real World Consequence

This is where things get even more complex, and Facebook’s influence requires further scrutiny.

As per The New York Times:

“A poll in May by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that only about half of Americans said they would be willing to get a coronavirus vaccine. One in five said they would refuse and 31 percent were uncertain.”

US medical leader Dr Anthony Fauci has also highlighted the same concern, noting that “general anti-science, anti-authority, anti-vaccine feeling” is likely to thwart vaccination efforts in the nation.

Of course, the anti-vax movement can’t purely be linked back to Facebook, but again, the evidence suggests that the platform has played a key role in amplifying such in favor of engagement. That could see some regions take far longer than necessary to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, so while the debate itself may seem relatively limited – and Facebook had allowed anti-vax content on its platform till last year, when it took steps to remove it – the actual consequences can be significant. And this is just one example.

The QAnon conspiracy theory had also been allowed to gain traction on The Social Network, before Facebook took steps to remove such last month, the violent ‘boogaloo’ movement saw mass engagement on the platform till Facebook announced new rules against such back in June, while climate change debates have been allowed to continue on the platform under the guise of opinion. In each case, Facebook had been warned for years of the potential for harm, but the company failed to act until there was significant pressure from outside groups, which forced its response.

Is that because Facebook didn’t consider these as significant threats, or because it prioritized engagement? It’s impossible to say, but clearly, by allowing such to continue, Facebook benefits from the related discussion and interaction on its platform.

The history shows that Facebook is far too reactive in these cases, responding after the damage is done with apologies and pledges to improve.

Again, as noted by Kendall:

“There’s no incentive to stop [toxic content] and there’s incredible incentive to keep going and get better. I just don’t believe that’s going to change unless there are financial, civil, or criminal penalties associated with the harm that they create. Without enforcement, they’re just going to continue to be embarrassed by the mistakes, and they’ll talk about empty platitudes… but I don’t believe anything systemic will change… the incentives to keep the status quo are just too lucrative at the moment.”

This is where the true conflict of open distribution platforms arises. Yes, it can be beneficial to give everyone a chance to have their say, to share their voice with the world. But where do you draw the line on such?

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg could clearly prefer for Facebook not to intervene:

“People having the power to express themselves at scale is a new kind of force in the world — a Fifth Estate alongside the other power structures of society. People no longer have to rely on traditional gatekeepers in politics or media to make their voices heard, and that has important consequences. I understand the concerns about how tech platforms have centralized power, but I actually believe the much bigger story is how much these platforms have decentralized power by putting it directly into people’s hands. It’s part of this amazing expansion of voice through law, culture and technology.”

And that may reveal the biggest true flaw in Facebook’s approach. The company leans too far towards optimism, so much so that it seemingly ignores the potential damage that such can also cause. Zuckerberg would prefer to believe that people are fundamentally good, and we, as a society, can come together, through combined voice, to talk it out and come to the best conclusion.

The available evidence suggests that’s not what happens. The loudest voices win, the most divisive get the most attention. And Facebook benefits by amplifying argument and disagreement.

This is a key concern of the modern age, and while many still dismiss the suggestion that a simple social media app, where people Like each others’ holiday snaps and keep tabs on their ex-classmates, can have serious impacts on the future of society, the case, when laid out, is fairly plain to see.

Investigations into such are now taking on a more serious tone, and the 2020 Election will be a key inflection point. After that, we may well see a new shift in Facebook’s approach – but the question is, will that, once again, prove too late?

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Social Media Today can be found here ***