Kathrin has been ‘brainwashed’ by a nation before — now she’s worried her friends are becoming ‘converts’

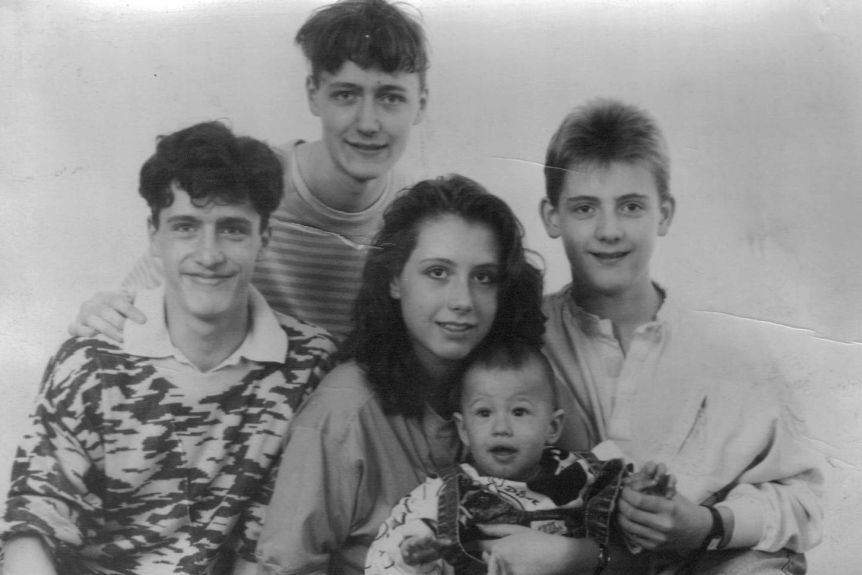

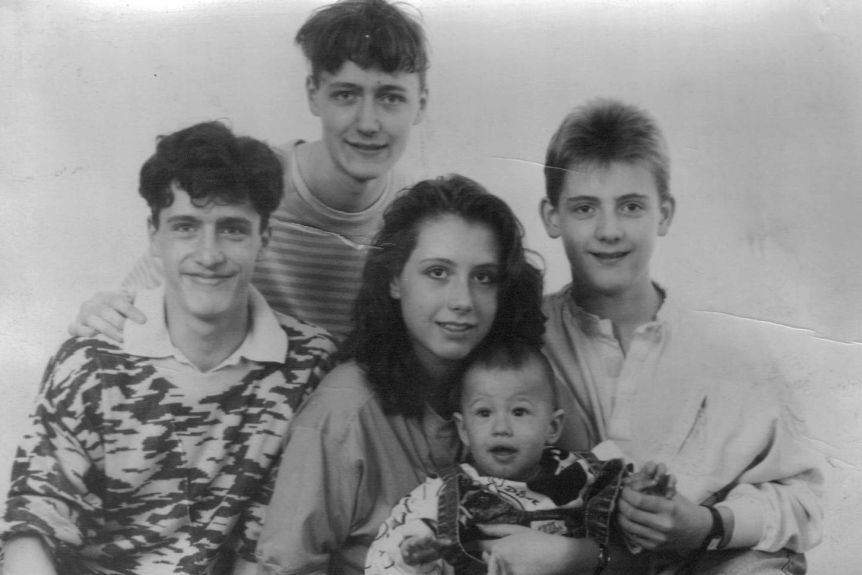

Kathrin grew up “pretty brainwashed” in East Germany during the Cold War.

Once a communist girl scout, she remembers the steady drum beat of state propaganda in the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

To stop an exodus to the West, the country’s leaders had built the Berlin Wall — physically and ideologically dividing the city.

But Kathrin says the country’s leaders needed to first spread enough distrust for the population to agree to being cut off from friends and family by thick slabs of concrete.

“That wall lasted 30 years or so and has done so much damage,” she says.

Kathrin thought she’d left that paranoia behind after she emigrated in her teens.

But since the pandemic started she’s found herself embroiled in a new battle over truth and narrative.

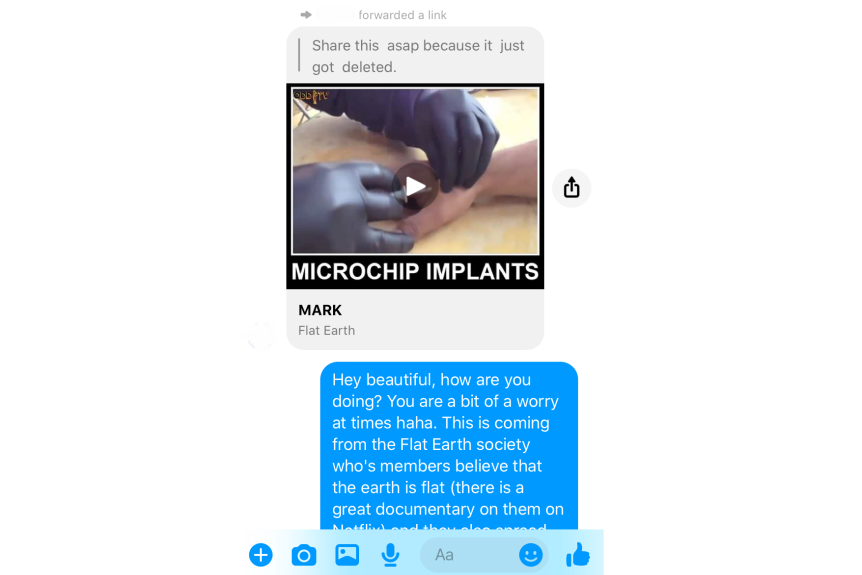

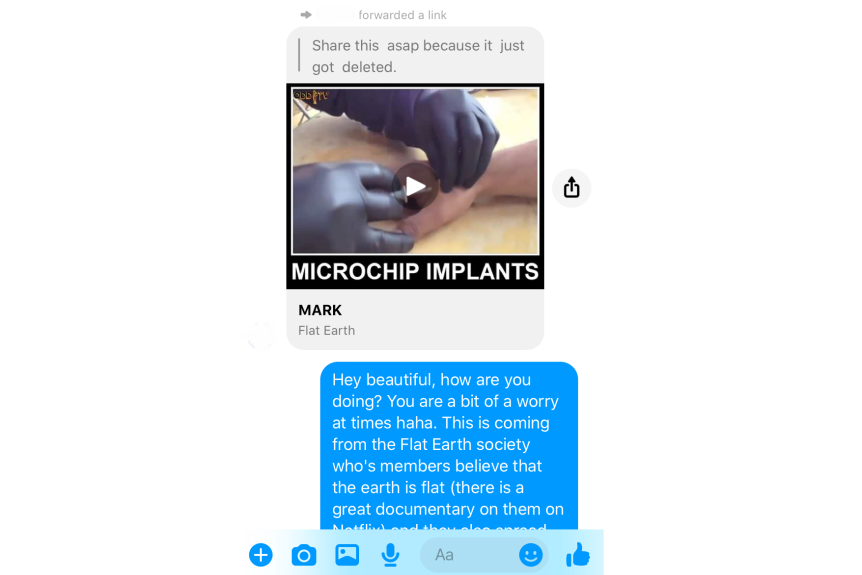

Earlier this year, while in lockdown on Sydney’s North Shore, her friends began sending her “mind-boggling” links suggesting COVID-19 was part of some giant conspiracy, or an attempt to microchip the population.

Kathrin approaches these conversations with her friends cautiously and tries to hear them out.

But she’s lost at least one friend and is drifting away from others.

“I find it really upsetting to see friends getting dragged into this whole world of false information and really becoming convinced and converts,” she says.

Some of these conspiracies have flourished on platforms like Facebook and YouTube, and among communities predisposed to such views.

And, in an echo of Kathrin’s past, researchers now believe nation states may also be playing a part in spreading false information about the pandemic.

A history of nation states using conspiracies

Disinformation is the coordinated spread of false or misleading information, often for political or financial gain.

A crisis — such as a pandemic — is a ripe moment for such a campaign.

It’s clear that states are pursuing their own agendas amid the pandemic, says Renee DiResta, research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, who studies how information spreads online.

“There’s disinformation that you push out to your own people and there’s disinformation that you push out to overseas,” she says.

“The latter is because you have some sort of geopolitical interest in maybe weakening an enemy.”

As an example, she points to the claim from Iranian leaders that the coronavirus was designed as a bioweapon in the US — a virus “genetically tailored” to the genome of the Iranian people.

“That propaganda is designed to shore up their reputation with their own people by saying this was a thing that was done to us by outsiders,” she says.

Nation states also leverage existing suspicion for disinformation.

For example, Chinese and US officials have both questioned whether the other nation is to blame for creating SARS-CoV-2 — a narrative that has also spread online and in parts of the media.

One theory claims that the virus was brought to Wuhan by the United States during the world military games in November 2019.

Meanwhile, in the United States, some politicians speculated that the novel coronavirus escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Neither of these theories has been backed up with firm evidence.

Dr Douglas Selvage, a historian of disinformation at Humboldt University in Berlin, agrees that the US and China have been pointing fingers at one another during the pandemic.

He says state-controlled media in Russia has also been amplifying COVID-19 conspiracy theories, particularly those focused on the US.

“Russian news outlets, or propaganda outlets, like RT, formerly Russia Today, or Sputnik News tend to report on…various conspiracy theorists in the West,” he says.

These techniques aren’t new.

Nation states have long used health crises to spread disinformation.

“Historically, one of the really common themes we’ve seen from China and Russia in particular is the idea that outbreaks are tied to some kind of bioweapon,” Ms DiResta says.

“That stretches back to the Cold War.”

A Cold War disinformation campaign

Dr Selvage has pieced together a campaign of state-led disinformation during the Cold War, coordinated by the Soviet KGB and the GDR’s secret police, the Stasi.

Its goal was to discredit the United States internationally, he says, and to create domestic tension.

How exactly? By pinning the then-emerging HIV-AIDS epidemic on the US Government.

The story went that the virus had been developed as a bioweapon at Fort Detrick, Maryland.

Russian operatives tried to prompt journalists to promote the theory, and even sent them information brochures about the claim.

“They would seek to try to put articles in the foreign press or to get articles published based on their disinformation thesis,” says Dr Selvage.

Several African publications ran articles airing these claims.

The first instance likely stretches back to India in 1983 in the Patriot newspaper, with an article entitled ‘AIDS May Invade India’.

“It suggested that The US was medically experimenting with this new biological weapon in neighbouring Pakistan, [and that] it could come over the border into India,” says Dr Selvage.

Conspiracies bloom when people are frightened or marginalised. But they rarely emerge out of nowhere.

Dr Selvage says the HIV-AIDS disinformation campaign leveraged off existing fears in the US at the time.

During the fear and trauma of the early AIDS outbreak in the United States, the Reagan administration was openly hostile towards LGBTQ people.

And Dr Selvage says speculation that the virus was part of a campaign of persecution was already spreading in that community.

Around 1985, similar conspiracies were also publicised in local media among parts of the African American population.

He suggests the theory took root in part because the US government had carried out unethical medical experiments in the past.

For example, Dr Selvage points to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which was run by the U.S. Public Health Service.

The study examined a cohort of African Americans who had contracted syphilis, from 1932 to the 1970s.

But their health was examined without informed consent, and they weren’t provided with penicillin as a treatment even after it was proven to be effective for the disease in the 1940s.

“These individuals were not treated, and some of them just basically died,” Dr Selvage says.

“Conspiracy theorists mentioned … ‘see it’s just like Tuskegee all over again’.”

Echoes of Kathrin’s past

Even if nation states are actively trying to sow division, it’s still unclear whether those efforts really cause people to alter their beliefs or their behaviours.

Douglas Selvage also argues that various strands of false narratives likely feed into one another, given there are many who can benefit from spreading misleading health information.

There are what he calls “conspiracy entrepreneurs”, who want to spread a conspiracy theory for their own purposes.

“Either to win support for their political movement, usually its right-wing or left-wing extremist movements, or in some cases as people who are just trying to sell [something],” he says.

“We definitely see today that there’s sort of this cycle of misinformation and disinformation.”

Kathrin’s concerned that her friends don’t look closely at where the content and ideas they’re sharing have come from.

“Most people will go ‘oh that was reposted by my friend or by my relative’, they don’t really know what the source is,” she says.

“You don’t necessarily go to the account and research the account and go like ‘oh that’s linked to Russian media’. Most people wouldn’t do that research.”

It’s difficult to disentangle exactly who’s behind online health misinformation and disinformation today, and what their motivations might be.

However, after her education in the GDR, Kathrin says she knows how drastically our views can be moulded by false or misleading narratives.

When she left East Germany, she felt like she had to relearn history.

“I remember when someone told me later on that ‘oh Stalin killed millions of people’ and I was like ‘oh I never heard that!’ That wasn’t part of our education,” she says.

Kathrin’s worried that misinformation during this pandemic could lead to similar impacts.

And she’s concerned for the safety of her family and her community if people fall for false conspiracy theories and begin to question all official health advice.