QAnon shows that the age of alternative facts will not end with Trump

In the past few weeks, QAnon—a right-wing conspiracy premised on the idea that Donald Trump is working with military intelligence to bring down a global ring of child-eating pedophiles—has been the object of considerable media speculation. Though the conspiracy has been around for years, QAnon has found new life with Instagram influencers, TikTok teens, and a shocking number of congressional candidates, more than a dozen of whom will appear on ballots in November.

In terms of content, QAnon has quite a bit in common with other mostly online conspiracies, from 9/11 Truthers to Pizzagate. Arguably, though, what makes it distinct is the primary text—Q’s “drops,” as they came to be known—that holds the entire conspiracy together. Several times each week since late 2017, “Q,” an anonymous account claiming to be a Trump administration insider, posts on the imageboard 8Kun (previously 8Chan), a hub for the so-called “alternative right.” Q’s submissions are obscure by design. Full of strings of letters and numbers, vague references to political figures, and open-ended questions, the drops are meant to be decoded.

By doing so, Q researchers—who also call themselves “Bakers,” turning “Crumbs” of information from Q into insider knowledge about current events—believe they are paving the way for the “Great Awakening,” an earth-shattering event in which all of Trump’s enemies will be arrested for being Satan-worshipping pedophiles. In short, QAnon doesn’t simply offer readers insider insight into current events, but also provides them the ability to take part in shaping those events through an intricate research process. (In June, this inspired the #TakeTheOath hashtag on Twitter, a sort of far-right ice bucket challenge where believers filmed themselves taking an oath to work as “digital soldiers.”) While many conspiracies encourage readers to doubt mainstream sources, QAnon takes things one step further by building an entire knowledge-making institution of its own. And that takes some serious effort.

This observation sits uneasily with the journalistic consensus on QAnon, namely that its adherents are gullible dupes, immune to “facts” and “reason,” driven to insanity by their fealty to Trump. Adrienne LaFrance, summarizing her feature on QAnon in The Atlantic, offered that “[QAnon] is premised on a search for truth, [but] adherence requires the total abandonment of empiricism. This is a mass rejection of reason.” Comforting though this analysis is (in part because it’s also a way of saying “Well, I’m not the crazy one”), it sidesteps a thornier—but very important—question: If QAnon is so wrong, then why do people still believe in it?

To answer that, we set out to understand QAnon researchers on their own terms, rather than dismissing them out of hand. Among sociologists, this tactic is known as the symmetry principle. Put crudely, it proposes that “true” and “false” beliefs be explained the same way—as equally constructed. The point isn’t to assert that true and false are somehow equally valid, but to strategically set aside claims about who is “right” and to study how competing knowledge claims are assembled, scrutinized, and accepted by their communities. This led us to spend several months observing self-identified researchers on QAnon Facebook groups and imageboards, watching YouTube videos and reading books by QAnon influencers, and browsing the surprisingly rich online databases that Q researchers have created to aid them in their efforts. And what we observed didn’t line up with the public image of QAnon as bumbling, media-illiterate boomers willing to accept any lurid story about corrupt, pedophilic globalists.

To see how this works, it helps to examine how “Bakers” turn Q’s cryptic posts into “Proofs.” Proofs are a kind of “Bread”—QAnon enthusiasts’ term for worthy research—and offer authoritative interpretations of Q’s vague statements, thereby proving that Q is authentic and that Q’s drops explain or predict future events. Proofs take many forms, including lengthy PDF e-books and video monologues, but one of the most common is what disinformation researchers Peaks Krafft and Joan Donovan call “Evidence Collages.” These are Microsoft Paint creations with lots of red arrows that look like Carrie’s conspiracy wall in Homeland. The images arrange seemingly disparate events (say, several Q drops, news stories, and tweets by Donald Trump) into a single diagram in order to suggest that they are all interrelated and part of a larger plot.

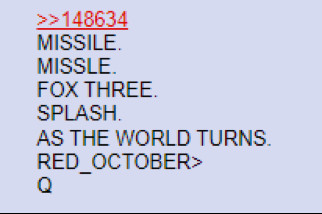

One example. On December 22, 2017, Q drop 432 was published on 8Chan, once the primary hub for Q research:

Drop 432

Almost immediately the /qresearch/ community on 8chan and beyond began throwing out possible explanations. Bakers pored over the text of drop 432, focusing on missing letters, misspellings, unorthodox patterns, punctuation marks, and other potential “clues.” In this case, Anons focused on the missing i in “missile.” They suggested it might mean “Miss Lee the reporter/hostage ‘rescued’ by Bill Clinton from NK” (a reference to the reporter Euna Lee, who was captured in North Korea in 2009) or “a ‘missile’ that’s been taken over in-flight by an unintended party.”

Others began looking for alternative meanings behind specific terms, such as in the Air Force lingo “splash” and “fox three.” Still others sought out seemingly relevant articles from a truly impressive range of mainstream and not-so-mainstream media, such as this post on the Skunk Bay Weather Blog about a possible missile launch off the coast of Washington State. Others still took the photo of the “missile launch” and compared it against Google Maps to attempt to determine its origin and trajectory, or sought out possible explanations in publicly available databases including FAA incident logs and tracking sites like FlightAware. Some of these stabs in the dark might seem absurd—and indeed, Anons were quick to reject interpretations they regarded as overly fantastical, based on unfounded information, or from “biased” sources. Information in one article from Vice was summarily rejected for being too leftist, while the disreputable blogger Kevin Annett was elsewhere considered too much of a conspiracy theorist to be cited in “serious” Q research.

In the later proof “Rogue Missile Attack Intercepted” (shown below), Q researchers combined six Q drops from 2017 and 2018 with supplementary material to make the argument that a rogue missile attack against Air Force One in June 2018 was thwarted at the last second. Not only did this suggest the hidden meaning behind drop 432—it also implied that Q (once again) appeared to have predicted future events, validating Q and the QAnon conspiracy.

These kinds of hypotheses slowly transform into “Bread” in three ways. First, Q can pop up again in the thread and offer their stamp of approval, as they did to the Anon who dug up the Air Force glossary page to define “splash” and “fox three.” In such cases, this interpretation becomes canon and starts being referred to in the thread and future proofs. Second, once the thread gets to a certain length it is closed and archived, and an Anon writes a brief summary that includes “notables”—posts that the thread maintainer thinks are interesting or insightful. While any Anon can nominate a post for notability, what’s included is fairly subjective and left to the discretion of whoever is tending the thread. And since Q researchers don’t want to do what we did and dig through thousands of posts, they often simply refer to these notables rather than reading through an entire thread, thus privileging any post that’s included.

Finally, a motivated Anon can consolidate interpretations into an evidence collage (as in the “Rogue Missile Attack Intercepted” proof), YouTube video, Medium post, or even a Trello board. These neatly packaged proofs can travel widely on social media, often completely decontextualized or not even mentioning QAnon, and create a fixed version of a particular interpretation even if the thread hadn’t demonstrated particularly widespread agreement.

Then, upon Q’s next drop, the process begins anew:

While QAnon participants can often seem crazy, irrational, or credulous, our research suggests that their collaboration creates a populist expertise that provides (and, crucially, justifies) an alternative to knowledge generated by “mainstream” institutions. Put differently, QAnon does the work of constructing alternative facts. And just as individual pieces of data must be validated in mainstream institutions through processes like peer review and reproducibility, QAnon researchers have found a means of validating their own claims in their interpretation of the world.

Bakers embrace this body of “homegrown,” community-generated information because it shapes and supports their own beliefs about what is “really” happening in the world. When QAnon attacks Wayfair for selling trafficked children marketed as overpriced cabinets or shower curtains, they’re doing so based on a preexisting body of knowledge that has already “proved” the existence of enormous global child-trafficking operations. In QAnon’s understanding of this cabal, coded language is normal and kids are sold to global elites to be harvested for adrenochrome, a(n actual) by-product of adrenaline that some Q advocates believe can unnaturally extend its user’s life. If you accept that premise, secretly buying kids from a discount furniture site is perfectly logical.

Fifteen years ago, media theorist Henry Jenkins’s notion of participatory culture was all the rage among technologists and teachers. Jenkins looked at Star Trek fans and teen fanfiction writers and was inspired by their use of proprietary media products for their own creative ends. He was also interested in how fans interpreted texts—how they worked together to criticize and debate television shows and Harry Potter. His work, along with that of legal scholar Larry Lessig, spurred a movement for copyright reform and so-called Free Culture. We all assumed that participation was good, even democratic—or at least better than blindly consuming corporate-controlled media. But we see the exact same dynamics at work in QAnon as in fan communities.

Rather than bringing their expertise to bear on old episodes of Supernatural, Bakers analyze Trump’s tweets and Q’s ramblings about missile defense. They form a supportive community, praising each other’s efforts and writing introductory documents for newbies. And they believe this is all very significant; that they are not political “larpers” (Live Action Role Players) but are engaging in a “legitimate” form of political participation. QAnon shows us that we can’t characterize participatory culture as uniformly positive. Instead, we theorize QAnon as a dark participatory culture.

Our work also questions the tenets of current media literacy programs, which attempt to empower individuals by teaching them to “think critically,” “do their own research,” and evaluate their sources. This is often cited as a panacea for disinformation, fake news, and all manner of online toxicity. Yet our research shows that many Bakers already do these things, and defend the validity of the conspiracy on this basis. Bakers constantly exhort one another to “cite your sources” and “research for yourselves.” Likewise, the pinned post in one of Facebook’s largest QAnon groups instruct Bakers to be suspicious of hyperpartisan clickbait sites. Finally, Anons require all theories to have evidence, and they strongly reject sources they think are too liberal, too disreputable, or too out-there. By illustrating the gap between media literacy in theory and in practice, our research shows that simply encouraging people to “think critically” and “evaluate their sources” isn’t a meaningful check against conspiratorial thinking—in fact, it may contribute to it.

As we are writing this, in August 2020, QAnon is being pushed off of mainstream social media platforms, though with varying success. Twitter recently deleted several thousand accounts, while TikTok muted QAnon-related hashtags; Facebook has also moved to delete thousands of private QAnon groups. The truly dedicated Q researchers, of course, will regroup on other platforms with more permissive content guidelines, like Parler, Gab, or Discord. More casual researchers may simply move on to something else. But the power behind populist expertise, whether or not it’s expressed as QAnon explicitly, will continue to beguile partisans. Just as Trumpism will outlast Trump no matter what happens in November, the age of alternative facts has only just begun.

RELATED: When the news becomes religion

Alice Marwick and William Partin are the authors. Alice Marwick is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she researches the social, political, and cultural implications of popular social media technologies. She is the author of Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Attention in the Social Media Age, and her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, and The Guardian, among others. William Partin is a research analyst in the Disinformation Action Lab at Data & Society, where he helps to monitor and analyze disinformation campaigns. He has contributed features on culture, technology, and finance to The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and Variety, among others.

TOP IMAGE: Adobe Stock