Our Leader’s Life Is at Risk. Cue the Conspiracy Theories.

The conspiratorial speculations swirling around Donald Trump’s illness were inevitable. I’m not saying that just because the White House’s mixed signals and lack of transparency have made it difficult to know what’s going on, though that hasn’t helped.

Nor am I blaming social media, which may be a conduit for these rumors but did not cause them. Any time a president faces a life-threatening incident, conspiracy theories follow, even without a big information gap or credibility vacuum to fill.

When Andrew Jackson survived an assassination attempt in 1835, for example, pro-Jackson newspapers — and the president himself, in an impolitic moment — accused Senator George Poindexter, Democrat of Mississippi, of plotting the murder. As Jacksonian congressmen convened an investigation, some of Jackson’s critics retorted that the whole incident might have been a false flag, with the president hiring the gunman to gain public sympathy.

The first two presidents to actually die in office were William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor. Both were felled by illness, but rumors spread that each had died at the hands of a wicked cabal. When Abraham Lincoln was elected, several supporters wrote him to warn against the plotters.

“General Harrison lived but a short time after he was installed in office,” one letter declared, and “General Taylor lived but a short time after he took his seat.” It continued, “You, sir, be careful at the king’s table what meat and drink you take.” Another reported that “I have often heard it stated by physicians, that it was an undoubted fact, that our two last Whig presidents, Generals Harrison and Taylor, came to their sudden and lamentable ends by subtle poisons.”

Those purported plots featured prominently in John Smith Dye’s “The Adder’s Den,” an 1864 conspiracy tract that treated both deaths — and the assault on Jackson too — as parts of a “Parallax View” –style series of covert ops by Southern slaveholders. This wasn’t seen as a fringe position: The book was excerpted in The Chicago Tribune, and The New York Times ran a respectful notice that told curious readers they should “get this pamphlet and read it for themselves.”

Nor did such notions disappear after the Civil War. During the effort to impeach President Andrew Johnson, Representative James Mitchell Ashley, an Ohio Republican, declared that both Harrison and Taylor had been “poisoned for the express purpose of putting the vice presidents in the presidential office.”

By that time America had another dead president. Lincoln’s death immediately set off talk of conspiracies larger than that of John Wilkes Booth and his confederates, and Dye produced a new edition of his book blaming the same vast Southern conspiracy for Booth’s bullets. Over the years, more Lincoln theories would emerge, attributing the murder to everyone from the vice president to the Vatican.

The next president killed in office was James Garfield, shot in 1881 by a disgruntled job-seeker named Charles Guiteau. The rumor mill quickly claimed the deed had been arranged by the Republican Party’s “Stalwart” faction, whose members included Vice President Chester Alan Arthur. (One newspaper, The Baltimore American, was agnostic about whether Guiteau had acted alone, but it called the killing a coup “whether the assassin had accomplices or not.”)

Next was William McKinley, assassinated in 1901 by Leon Czolgosz. Czolgosz was a self-described anarchist, so the police promptly rounded up anarchists in jurisdictions around the country to interrogate them. On Sept. 11, five days after the shooting, the New York newspaper The World asserted that the Buffalo police had uncovered evidence of a “great anarchist plot.” (A day later, in a follow-up article, Buffalo’s police chief called the accounts “pure fakes.”)

After Warren Harding fell ill and died in 1923, a story spread that the first lady had poisoned the philandering president. In “The 103rd Ballot,” his classic account of the 1924 Democratic convention, Robert K. Murray mentions a more outré idea: Some anti-Catholic cranks attributed Harding’s death to “hypnotic waves generated by the minds of Jesuit telepaths.”

Franklin Roosevelt’s death inspired another assortment of theories. One tract, first published in 1948, suggested that a Communist waiter had served Roosevelt “an Oriental poison handed down from the days of Genghis Khan.” In a twist, the book claimed that this crime took place at the Tehran Conference of 1943, that Roosevelt was either dead or incompetent soon after he returned to America, that an actor then played him in public, and that this double was the man who died in 1945.

That was, admittedly, not a popular belief. But the fears that followed the 1963 slaying of John F. Kennedy were downright mainstream. At their peak, in 1983, an ABC News poll found 80 percent of Americans considered it more likely than not that there was a conspiracy to kill Kennedy.

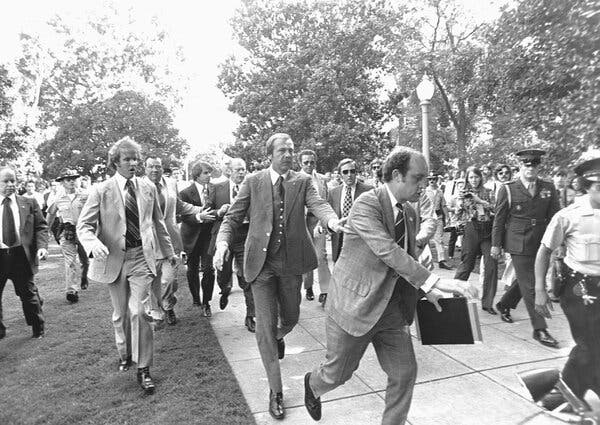

When Gerald Ford survived a pair of murder attempts in 1975, stories circulated that Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, or perhaps a group of Navy brainwashers, had pulled the strings of the would-be assassins, one of whom was the Charles Manson acolyte Squeaky Fromme.

The future president Ronald Reagan played footsie with a different idea: At a 1979 meal with the columnist Jack Germond, Germond recalled, “Reagan suddenly brought up the two assassination attempts against Ford. The timing of these episodes, particularly the second, he said, was just a little bit suspicious. Ford had been the beneficiary of ‘the sympathy vote’ because of Squeaky Fromme, and he, Reagan, had always wondered about whether it might have been arranged for political purposes.”

Reagan himself survived a shooting two years later. His vice president, George H.W. Bush, happened to have some ties to the gunman’s family, and conspiracists have been chewing on those connections ever since.

When a powerful man has a fatal or near-fatal experience, people are bound to speculate no matter what — conspiracies about the powerful are a durable phenomenon in American politics, circumstances aside. But such speculations will flourish more in some social contexts than others.

There was a lot more public theorizing about Jackson’s brush with death than Ford’s or Reagan’s, for reasons ranging from the reactions of the president to the more intense partisanship of the 1830s press. In Mr. Trump’s case, his illness is part of a pandemic that has turned American society upside-down — and epidemics themselves are machines for generating conspiracy rumors. That’s a potentially potent combination.

And it’s one we’ve seen before. In 1857, there was a lethal outbreak of dysentery at the National Hotel in Washington; three congressmen died, and President-elect James Buchanan became sick. Naturally, conspiracy theories exploded. Some Southerners imagined an abolitionist plot.

John Smith Dye, casting his suspicions in the opposite direction, proposed a rather Rube Goldbergish scheme in which Southern agents poisoned the hotel’s supply of lump sugar. Southerners drink coffee, Dye postulated, and coffee drinkers use granulated sugar; so the Southern diners would be spared and the tea-sipping Northerners killed.

One writer painted an even more paranoid portrait of weaponized disease, and not just at the National Hotel. An 1868 article in The New-York Tribune claimed that Washington had once been “free of malaria — that is, for Democrats; but when the new Republican Party began to gain strength, and it was possible that they might become the ruling power in Congress, the water of Washington suddenly grew dangerous, the hotels (particularly the National) became pest houses, and dozens of heretics from the Democratic faith grew sick almost unto death.”

More recently — that is, last week — a former Republican congressional candidate in California, DeAnna Lorraine, declared it “odd” that “no prominent Democrats have had the virus but the list of Republicans goes on and on.” This is not actually odd, because it is not actually true. But you can’t say the idea is unprecedented.

Jesse Walker is the books editor of Reason magazine, and the author of “The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.