Brainwashed: The echoes of MK-ULTRA

II.

Lloyd Schrier’s mother, Esther, had a difficult childhood, losing both her parents at an early age. In 1936, when she was four years old, her father died. Slightly more than a year later, her mother was diagnosed with a brain tumour and given a lobotomy. Unable to look after her children, she was committed to a psychiatric institution.

Esther and her older brother were moved around from the care of relatives and to foster homes, and suffered wherever they went.

But she was resilient and smart. In her late teens, she trained as a nurse and got a job at the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal. She met her future husband, Haskell Schrier, on a blind date. After they married in 1955, the couple became a fixture in Montreal’s Jewish social scene.

Three years later, after an uneventful pregnancy, she gave birth to their first child, a baby girl they named Lynn Carole. But the baby died of a staph infection when she was just three weeks old, and Esther struggled with her grief. Medical records show she felt she was responsible for her daughter’s death.

When she was pregnant again, two years later, she was still struggling with this guilt. Part of her “condition” identified in her medical records when she was admitted to the Allan was her anxiety over possibly losing another baby.

Haskell Schrier had read an article about Cameron and was impressed by the Allan’s reputation for offering cutting edge psychiatric care.

“Oh, ‘He was God-like,’ they would say,” said Lloyd Schrier. “I think he was head of the Canadian and the American psychiatric associations. And even the World Psychiatric Association.”

Cameron, a Scottish-born American psychiatrist, did hold all those titles at various points in his career, and he was the first director of the Allan.

What wasn’t known, until many years later, was that Cameron’s reputation also came to the attention of the CIA. They were interested in his psychiatric research that involved extreme sensory deprivation, drugs, and an intense repetition of recorded messages.

Three years after the CIA launched MK-ULTRA, they approached Cameron through the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology, a research foundation and one of their front organizations through which they funnelled money. They encouraged him to apply for a grant, which he did, and quickly received. From January 1957 to September 1960, the CIA gave Cameron $60,000 US, equivalent to slightly more than $500,000 today.

Esther Schrier entered the hospital in February 1960 to receive what her family thought was the best care money could buy.

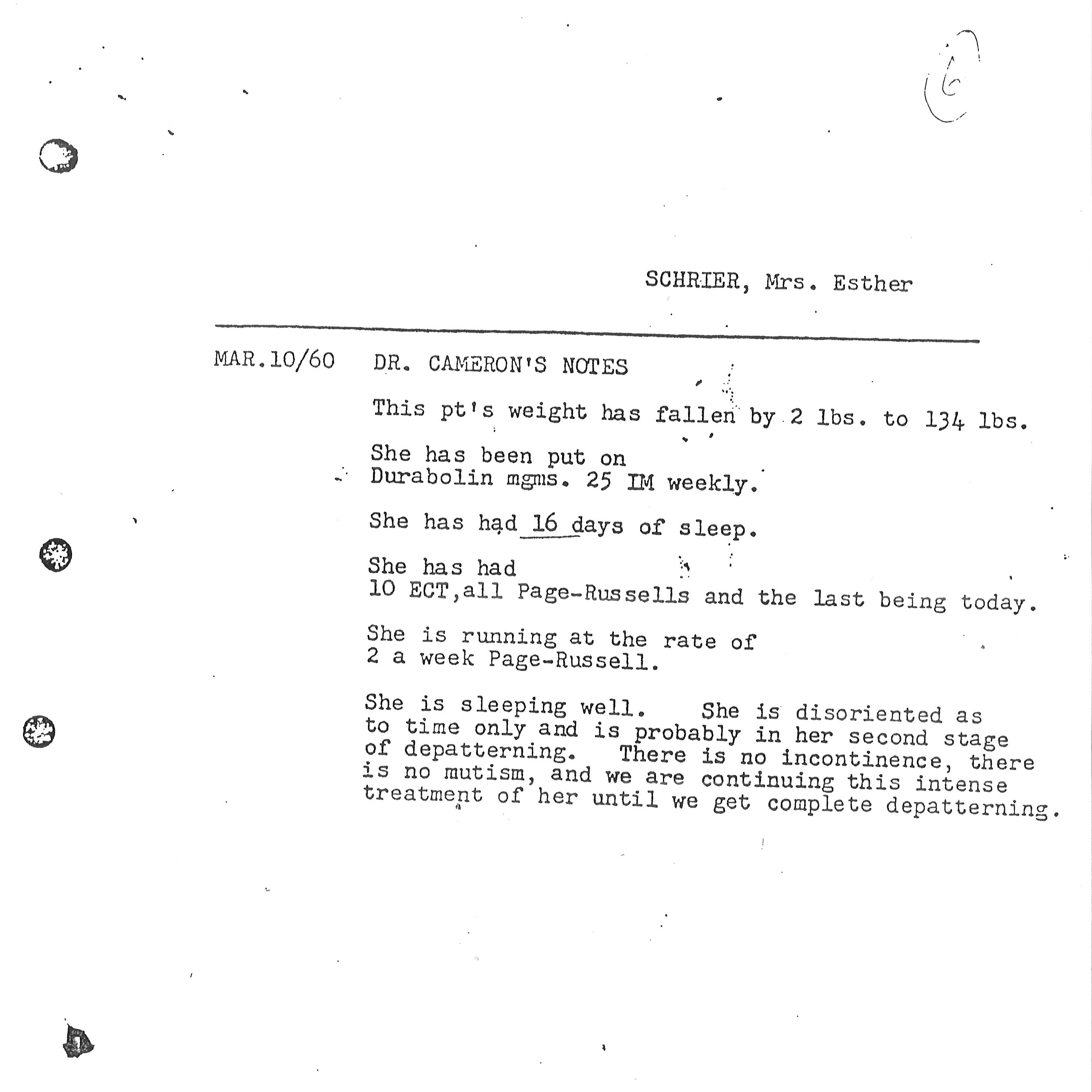

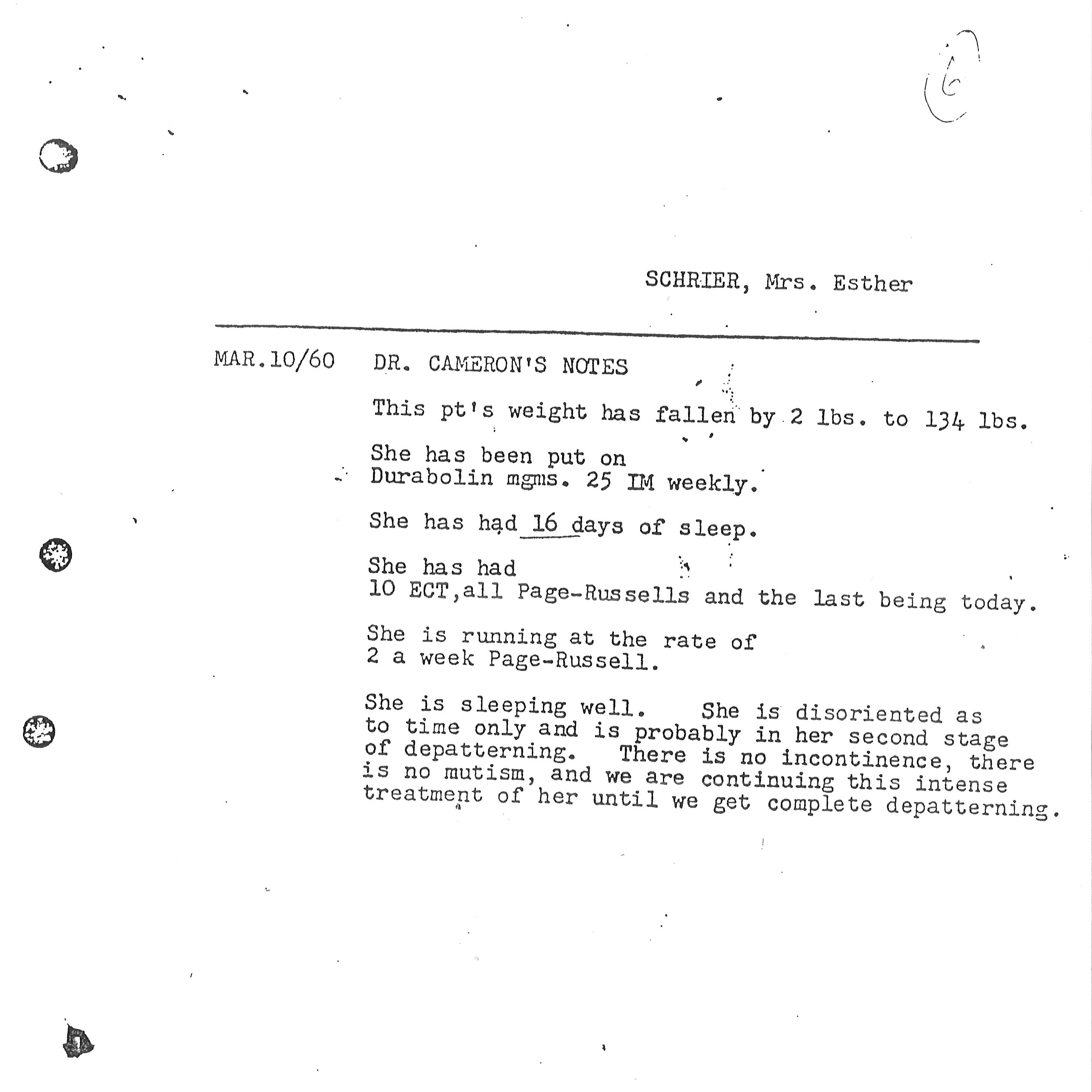

But her medical notes show disregard for her well-being and that of her unborn child right from the start.

She spent 30 days in what was called the “sleep room,” a place where patients were put in a drug-induced coma and roused only for three feedings and bathroom breaks per day. She lost 13 pounds that month. Her records show she couldn’t stand up because she was too weak.

She also underwent a treatment called “depatterning.”

Cameron believed that breaking down a patient’s minds to a childlike state — through drugs and electroshock therapy — would allow him to work from a clean slate, whereby he could then reprogram the patients. Part of his reprogramming regime would involve what he dubbed “psychic driving,” which meant playing recorded messages to the patients for up to 20 hours a day, whether they were asleep or awake.

These voices were played through headphones, helmets or speakers, sometimes installed right inside a patient’s pillow. Records show some patients would hear these messages up to half a million times.

By March 12, 1960, Esther Schrier’s medical records state that she was “considered completely depatterned.” She was incontinent, mute and had trouble swallowing.

“That’s crazy, to do that to a pregnant woman,” said her son. “When she woke from the sleep room, she didn’t know who my father was. She didn’t know it was her husband. I guess she didn’t know anything. You know, she used to tell me she had to relearn everything.”

Lloyd Schrier remembers his mother telling him that among the many things she forgot was how to boil water.

Several times during her treatments, she developed gynecological symptoms. Her records indicate she started to bleed and they brought in an obstetrician to treat her.

They would let her rest for four or five days and then resume treatments. Cameron’s notes say that on Aug. 17, 1960, six months after she entered the Allan, she had 29 electroshock treatments, with most of them of the extreme variety he was using. But because she was “now in her eighth month of pregnancy,” the treatments stopped.

On Sept. 27, 1960, Lloyd was born, and Esther Schrier said she felt helpless. She couldn’t remember basic life functions, let alone how to take care of a newborn.

Years later, in a 2004 BBC Scotland interview, Esther Schrier recalled how lost she had been.

“I had a new baby, and I didn’t know what to do with the baby. I had help, a baby nurse, but she had to have a day off and she left me a book, and I’ll just give you a little example [from the book]: ‘When you hear the baby cry, go to the room. Pick up baby and step by step how to feed the baby,’ and that was very frightening.”

Esther and Haskell Schrier are now deceased. She died of cancer in 2017 at the age of 84 and despite all she went through and what she lost, her son said she managed to live a full life and they remained close.

And he feels he was fortunate despite having lived under the dark shadow of what happened to his mother and uncertainty of how it impacted his health.

Many patients of Cameron emerged from the Allan completely broken, unable to find their way back to the lives they once lived. Relatives from across Canada have reached out to the CBC, describing the ongoing trauma the experiments have caused. Families were ripped apart by divorce or children were taken to foster homes. The grief rippled outward and spanned generations.

“I think I was lucky. I think the only side-effects that I know of, I guess in school, I was a bit slow in the beginning,” said Lloyd Schrier.

“But I ended up going through high school, and I went, we have in Montreal CEGEP, I did the two years, and then I went on to McGill, and I did a bachelor of commerce. So … I was able to get my degrees and everything.” But, he said, “I will never know what I could have been.”

- Listen to Episode 2 | Dr. Ewen Cameron’s experiments.