Facebook’s sweeping QAnon ban was surprisingly thorough

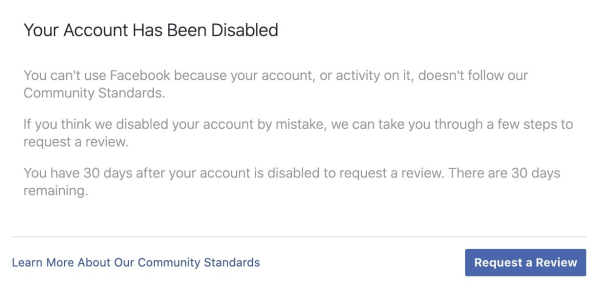

I got ejected immediately from Facebook last week when I tried to create a new group called “QAnon Lives.”

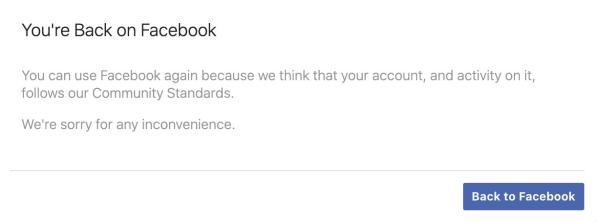

About 30 seconds later, I received another notice saying that my account had been restored and apologizing for any inconvenience. I am, however, not allowed to create groups for the foreseeable future.

I was on Facebook looking for signs of remaining QAnon groups or content after Facebook’s two-part crackdown on the group in August and October. In August, the company removed some but not all of the QAnon presence on its platform, banning or restricting more than 13,000 groups, pages, and Instagram accounts that “discussed potential violence.” After the QAnon crowd worked around the August ban, Facebook in early October implemented a full ban on Q-identifying groups, pages, and Instagram accounts.

QAnon is a digital cult that believes an international cabal of wealthy pedophiles who drink children’s blood is conspiring to bring down the U.S. and form a world government. It believes an anonymous government insider called Q is slowly leaking information on said cabal and is helping Donald Trump defeat it with the help of John F. Kennedy Jr., who is still alive. The group began growing on Facebook in 2017, and then got a major boost in popularity during the pandemic.

I was not a member of any QAnon group but I frequent adjacent groups whose members once posted QAnon-related material. Lurking around this week, I got the distinct impression that something had been ripped away, with an almost eerie silence left in its place. Not only are the Q groups and pages gone, but people seem hesitant to even mention the name.

It’s a striking change for a company that has been instrumental in helping the QAnon delusion spread. After years of trying to avoid totally removing offensive or deranged content from its site, it appears to have swung far in the other direction to stop the circulation of a harmful idea.

Searching for Q

Facebook banned QAnon by labeling it a “militarized social movement,” putting it in the same class with white supremacist militia groups. This cleared the way for the company to immediately disappear all QAnon groups and pages, destroy hundreds of Q-related hashtags, and prevent the search box from finding QAnon content and people. It also banned QAnon pages on Instagram.

Beyond QAnon member posts encouraging violence, Facebook said, those in the community have also falsely blamed members of far-left and far-right groups for starting the California wildfires, potentially making those people targets for retribution.

Now all the Q groups are gone from Facebook, and you can see from my experience how difficult it is to form or even find new ones.

I first tried using Facebook’s search engine to unearth QAnon people or content, but no matter how creative I got with my search terms I found almost nothing. The company already knows all the most-used search terms—everything from “the great awakening” to “Save Our Children” to “WWG1WGA (Where We Go One We Go All)”—and has disconnected them from Q content.

Even in the comments under posts of related content (conspiracy theories, or child exploitation), I could find few direct references to QAnon or QAnon ideas. I got the impression that people are now afraid to post such things for fear of having their accounts suspended.

Facebook users can still post QAnon content on their own personal pages, but even finding such pages proved difficult. I tried looking through people’s friend lists and followed possible Q believers back to their personal pages. I tried following suspected Q people from their comments in public conversations back to their personal pages. But after a couple of hours of trying, I found just one account that displayed QAnon symbols and language this way.

I asked around. One person in an antivax group told me that Facebook had sent her a warning just for trying to search for QAnon (which is believable, given my experience trying to set up a Q group). Another person, whose page showed signs of QAnon, jokingly wrote, “QAnon? what’s that?” A third person said I’d have more luck on Twitter and provided me with a hashtag to try.

Facebook’s treatment of QAnon is indicative of a shifting policy on free speech at the company. It increasingly errs on the side of restricting speech rather than enabling it, and there is a risk of going too far.

QAnon followers might be a bunch of loonies, but how sustainable is a policy of telling people they can’t assemble in online groups to discuss an idea (in this case, a conspiracy theory)? And if Facebook believes that the promotion of real-world violence is so central to QAnon’s beliefs, why continue to host personal pages that contain content about it?

QAnon’s huge popularity on Facebook—as well as its sudden demise—is a reminder of how different a place the social network is in 2020 compared to, say, 2014. I remember when it was mainly vacation pictures, baby pics, lots of cats, and Funny or Die videos. Now many of the feeds I’ve seen on the phones of friends and family are clogged with partisan venom and disinformation. Facebook’s main motivation for keeping its site upbeat and civil is for the sake of maintaining a good place to show ads. The company will have to work harder and harder to do that—even if that means giving up its free speech ideals.

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Google News can be found here ***