Republicans Claim Voter Fraud. How Would That Work?

Even before Election Day, Donald Trump cast doubts on Pennsylvania’s mail-in ballots. The Supreme Court’s decision permitting the state to accept absentee ballots for several days after the election, he tweeted, “is a VERY dangerous one. It will allow rampant and unchecked cheating.” As soon as the election is over, he told reporters on Sunday, “we’re going in with our lawyers.” Republicans are already in court, challenging the count of some mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania.

But there is no rampant fraud going on in Pennsylvania, and any judge with integrity and intellectual honesty should recognize the claim for what it is: specious. Fraud on a scale to affect a presidential election, or even to tip one state, would require planning, coordination, good luck and a high tolerance for risk. The chances of pulling it off are extremely slim.

Such a nefarious plot would require the foresight, many weeks or even months in advance, to know to focus the effort on Pennsylvania. The plotters might hedge their bets by targeting multiple states, but that just makes the effort more expensive, risky and difficult.

A conspiracy to fix the 2020 election in Pennsylvania would also need to muster tens of thousands of votes. In 2016, almost 6.2 million Pennsylvanians cast ballots for the presidency. Donald Trump won by 44,292 votes, 0.7 percent of the total.

Suppose the conspirators somehow knew this year that Pennsylvania would be tied but for their efforts. For the sake of argument, let’s say they decided to marshal 62,000 fraudulent votes, roughly 1 percent of the 2016 total and twice the 0.5 percent margin that sets off an automatic recount. (Even that seems to cut things a little close.)

How hard could it be to order up 62,000 illegal ballots?

The chance that 62,000 Biden supporters in Pennsylvania would spontaneously vote with a second, illegal ballot, either in person or by mail, is effectively zero. It’s hard to believe any voters would expose themselves to the risk of felony prosecution, fines and imprisonment, with no knowledge of whether anybody else was doing so too, in order to bring the Democrats one vote closer to victory in Pennsylvania. A fraud of the necessary size would have to be organized.

And how might that work?

Maybe a fraud mastermind would recruit a thousand accomplices, each of whom would generate 62 illegal ballots. All thousand of them would have to risk their reputation, resources and freedom to beat Donald Trump in Pennsylvania. They would have to be able to keep their work secret then and for all time — and trust their thousand co-conspirators to do the same.

The work of the thousand fraud wranglers would itself require a lot of ingenuity and a big dollop of luck. They might each try to persuade 62 people to vote a second time, but it would be a hard sell.

The recruits wouldn’t want to vote both in person and by mail, given how easy it is for election authorities to detect it. And unless they happen to be registered in two jurisdictions, they can’t vote in more than one — and they risk prosecution if they do. The conspirators would also have to gamble that none of the 62 (or more) people they contact is a secret Trump supporter or a Biden supporter with a healthy conscience.

Alternatively, the conspirators might each impersonate 62 legal voters, perhaps by requesting and returning mail-in ballots. This is also no easy task.

As a safeguard against fraud, Pennsylvania requires most people applying for a mail-in ballot to provide identification — either a state driver’s license or ID card number, or the last four digits of a Social Security number. So the fraud managers would somehow have to discover the correct ID numbers for all 62 voters.

Should even one actual voter turn out to vote or request a mail ballot too, their efforts might be undone, and they’d be exposed to legal jeopardy.

Now multiply all these difficulties by a thousand, because each of the thousand accomplices would face the same problems.

Finally, what if the fraud mastermind is a county election official and just adds 62,000 Biden votes to the tally (or omits 62,000 Trump votes)? Election officials are partisans, of course, and they oversee the vote count.

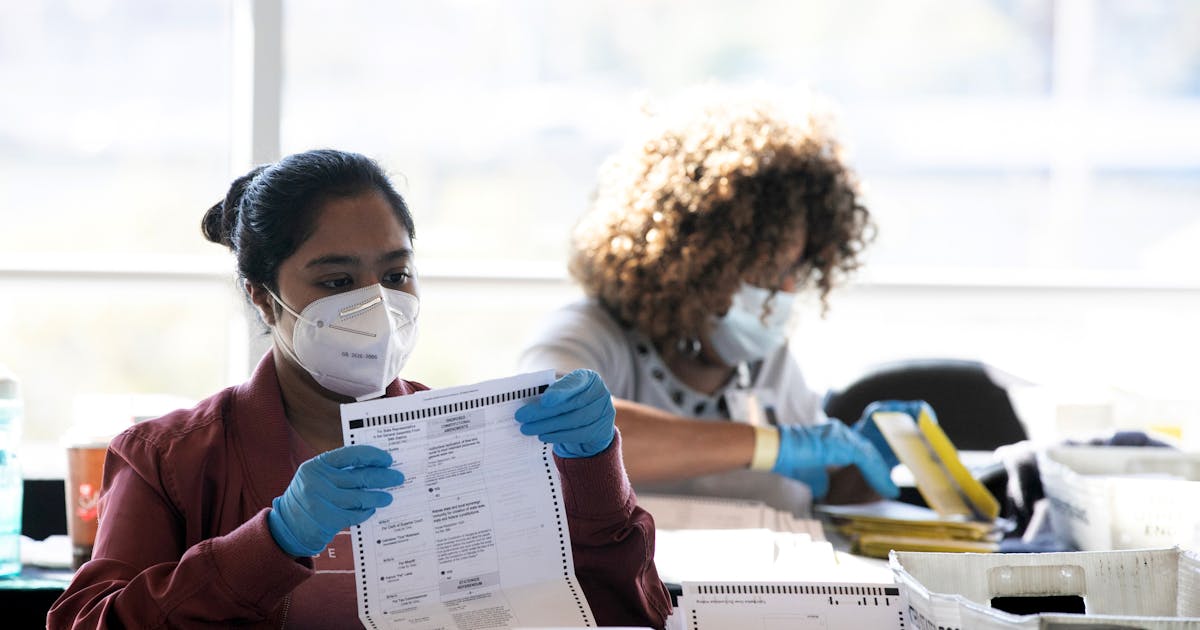

But most states allow partisan observers to monitor vote counting. Moreover, it might look a little suspicious if a county’s normal vote count is suddenly 62,000 larger or smaller. Tipping a presidential election at the counting stage would also require a lot of people acting in concert, organized a long time in advance.

The challenges to vote fraud on a scale sufficient to change the outcome of a presidential election are daunting, to say the least. To steal a presidential election would require, at a minimum, tens of thousands of votes (or even millions, if anybody really thinks the president was cheated out of a popular-vote victory in 2016).

The costs of committing vote fraud go up with the number of votes, and so does the likelihood of detection, prosecution and penalty.

This year, by the looks of it, many Pennsylvanians voted for the first time or for the first time in a long time, some of whom were perhaps motivated by animus toward President Trump.

But that’s not fraud. That’s democracy.

John Mark Hansen, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, was a research coordinator in 2001 for the National Commission on Federal Election Reform.