Anger builds in Black community over Trump’s claims of voter fraud in big cities

By Ashley Nguyen, Kayla Ruble and Tim Craig,

Salwan Georges

The Washington Post

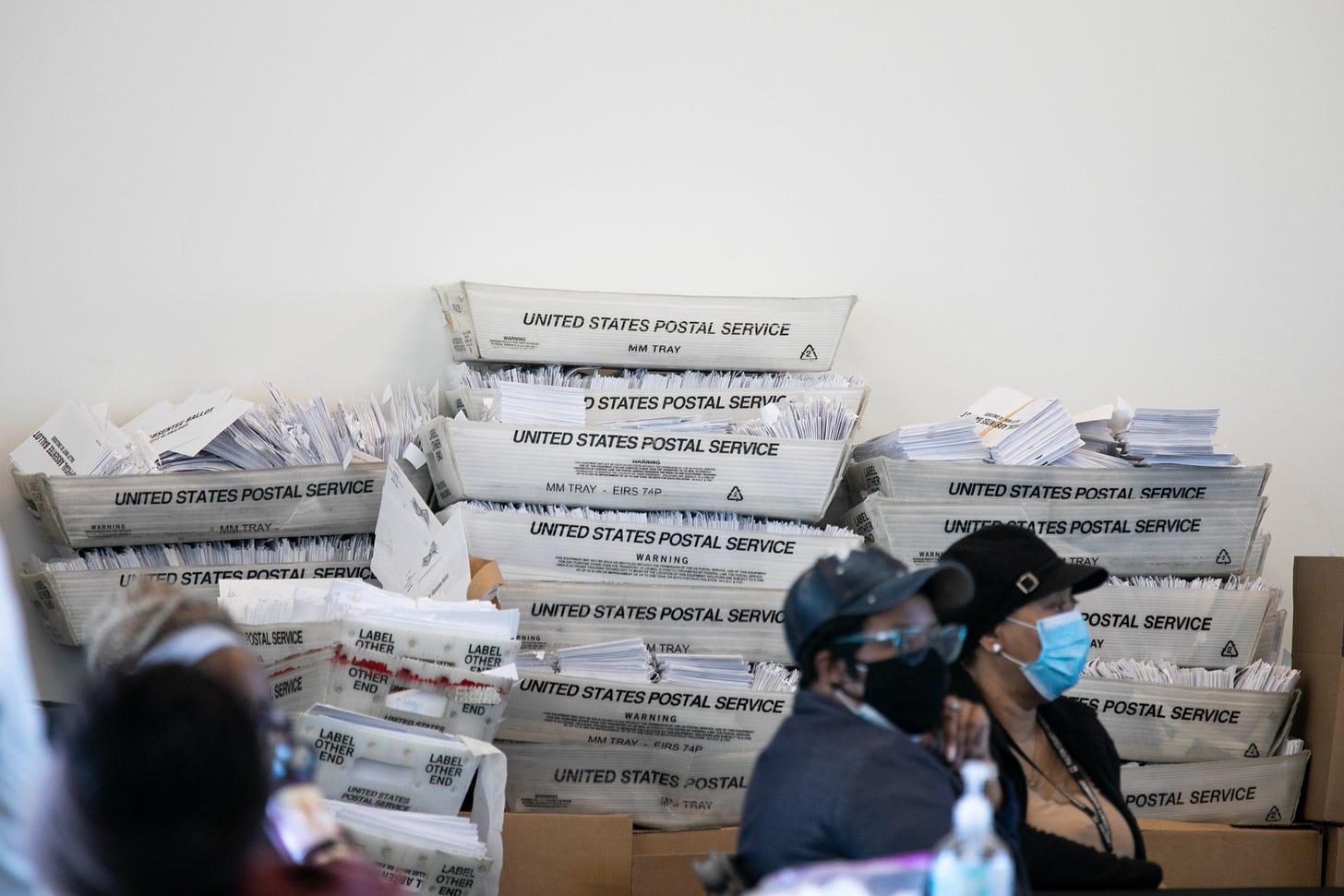

Poll workers process and count absentee ballots during the 2020 general election at the TCF Center in Detroit on Nov. 4.

MILWAUKEE — When Wisconsin Republicans opened an office earlier this year in the historical Bronzeville neighborhood, it was meant to be a physical symbol of President Trump’s commitment to urban voters. Signs on the window declared “Black Voices Matter,” and the address was on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

But on Friday, as state officials began recounting ballots in Milwaukee County at the request of Trump’s failed reelection campaign, the office had become, for many residents, a symbol of Republican hypocrisy.

“The president kept talking about Black voices mattering when he attempted to make inroads with the African American community,” said Cavalier Johnson, president of the Milwaukee Common Council. “Then he loses the election, and turns right around and targets the same communities that these Black folks came from.”

Johnson, who is Black, reflected deepening outrage over the president’s push for a recount in the predominantly Black county, which some characterized as an attempt to disenfranchise Black voters in a desperate and chaotic bid to stay in power. Though Trump courted Black voters — and improved his showing over 2016 — he and his allies are now trying to deny President-elect Joe Biden’s victory in key battleground states by targeting ballots cast in heavily Black cities such as Philadelphia, Detroit, Atlanta and Milwaukee, arguing that these Democratic strongholds are hotbeds of fraud.

In Michigan, where Biden won by more than 150,000 votes, one of two Republicans on the four-member Wayne County election board offered to certify ballots from every community in the county except Detroit. The board ultimately certified the vote, but a state-level certification decision set for Monday remains uncertain.

In Pennsylvania, where Biden is leading by about 80,000 votes, Trump’s legal team has argued that hundreds of thousands of ballots cast in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh should be declared void because GOP election observers were not allowed to watch the votes be counted.

And in Wisconsin, where Biden won by 20,500 votes, the Trump campaign is paying for a recount in diverse Milwaukee and Dane counties, but not in the rest of the state, which is largely White.

Trump and his allies have presented no evidence of fraud or widespread error in any of these cities, and courts have repeatedly declined to grant their requests to invalidate ballots. Still, the president shows no signs of backing down, prompting Black leaders, political analysts and historians to cry foul at what they described as tactics reminiscent of those used to suppress the voice of Black voters following the Civil War.

“It’s as vile now as it was during Reconstruction, when Democrats believed that Republicans were illegitimate and that Black voters had no right to be voting, and they did all of these terrorist activities to block African Americans from voting,” said Carol Anderson, professor of African American studies at Emory University. “It’s a very narrow, slippery slope, from saying ‘illegal votes’ to ‘illegal voters,’ so this attack on Black voters is real.”

In recent days, Republicans in Wisconsin and elsewhere have rejected assertions that their lawsuits and recount strategy is targeting Black voters.

Orlando Owens, chair of the Milwaukee North branch of the county’s Republican Party, said the GOP effort in Wisconsin is aimed at counties that have high concentrations of Democratic voters.

“It just so happens that a lot of Black voters are Democrats,” he said, noting that the University of Wisconsin at Madison is in Dane County, where there are a number of college voters but only 6 percent of county residents are Black.

“I don’t believe race has anything to do with it,” said Rick Baas, who heads the Republican Party of Milwaukee County’s media committee.

But on Friday, a top lawyer for the Biden campaign decried Trump’s efforts, saying it was involved in a “remarkably brazen attempt” to disenfranchise Black voters.

“This is straight out discriminatory behavior,” said Robert F. Bauer in a conference call with reporters.

Bauer and other legal experts have repeatedly stressed that Trump’s efforts to block the certification of votes in Michigan’s Wayne County or reverse the outcome of the race in Wisconsin is unlikely to succeed.

Yet, Trump’s efforts have left community rights leaders and voting rights activists rattled.

“People are anxious over that slim glimmer that he could somehow actually change the outcome,” said Fred Royal, president of the Milwaukee chapter of the NAACP. “But more than that, he’s trying to do all of this in the middle of this pandemic, where people are tired, and people are unemployed, and they are trying to feed their family, and teach their children who are not in school, and now he is putting us back through this recount process.”

Royal and other community leaders said they are angered that Trump is suggesting that there are more votes than people.

Biden received about 69 percent of the vote — 317,000 votes — in Milwaukee County this year. Four years ago, Democrat Hillary Clinton received 288,00 votes, about 65 percent of the vote.

The Rev. Greg Lewis, the executive director of the nonpartisan Souls to the Polls, which worked to boost Black turnout in Milwaukee, said that the claims of mass voter fraud don’t click.

“The blame is being set in Black communities for all the fraud, and that’s just nonsense,” said Lewis, who has worked with churches to mobilize Black voters amid hurdles, including the state’s strict voter identification law. “How can you have all the fraud when you have all these obstacles in place that make it so unusually difficult to vote in a city like Milwaukee, in a state like Wisconsin?”

Lewis said many voters he encountered were unenthused by the election, and reluctant voters wouldn’t spend time trying to commit fraud.

“These people don’t really care about the process because they don’t think anyone cares about them,” he said. They “don’t care about running out and trying to get a candidate in office, especially a candidate they don’t even care for.”

In Detroit, which has been at the center of the controversial efforts by Republicans to delay the certification of votes in Wayne County, local leaders were also incensed over questions about the legitimacy of the election.

N. Charles Anderson, executive director of the Urban League of Detroit & Southeastern Michigan, said his organization put out fliers, and held virtual events as they worked to get out the vote in the nation’s largest majority Black city. Now, Anderson sees Trump’s efforts to overturn the results as an “all out assault” on the Black vote.

“Voter intimidation and voter suppression has been aggressively played even before the election,” he said. “Now it’s even worse because you’re trying to suggest that you’re going to suppress the vote of hundreds of thousands of individuals, Black and White.”

Ken Kollman, director of research and a professor at the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan, said Trump is challenging the results in Detroit even though there have been only scattered allegations of voting irregularities there in recent years. But efforts to make the claims stick have been made easier by several recent major scandals involving big city mayors, including the 2013 conviction of former Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick on 24 counts of mail fraud, wire fraud and racketeering, Kollman said.

“These kind of attacks are made because they fit people’s preconceptions about government inefficiency and corruption,” said Kollman, who nonetheless believes Trump’s actions look increasingly “sad and tawdry” to many voters.

Regardless of whether Trump’s attacks on the integrity of the electoral process ultimately fail, Anderson cautions that they need to be viewed as yet another disgraceful chapter in the United States’ post-Civil War political history. Anderson believes Trump is borrowing a page from past politicians, knowing that racial division still works as a “political strategy” in broad swaths of the country.

“It is a way to create this aura that something went wrong in this election, to play to an audience that is hyped up on white supremacy,” Anderson said. “They need to understand how did this happen? How did our savior lose? . . . And the answer is, as the answer always is, ‘Those Black people stole it from us.’ ”

Ruble reported from Detroit. Craig reported from Washington.