Trump’s voter fraud yarn is unraveling. But it can still help the GOP.

As the month wore on, Republican leaders gradually acknowledged reality: that Trump lost and has no legitimate recourse. Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (Pa.) congratulated President-elect Joe Biden and encouraged Trump to “accept the outcome of the election.” Sen. Bill Cassidy (La.) tweeted: “President Trump’s legal team has not presented evidence of the massive fraud which would have had to be present to overturn the election. I voted for President Trump but Joe Biden won.” In an interview published this week, Attorney General William P. Barr said his Justice Department has “not seen fraud on a scale that could have effected a different outcome.”

The president, however, remains undeterred. On Wednesday, he tweeted out a Facebook link to a 46-minute recorded speech in which he railed against “corrupt forces … stuffing ballot boxes” and blamed the outcome on “fraud and abuse … on a scale never seen before.” Contesting the result of the presidential race, Trump said, “is not just about honoring the votes of 74 million Americans who voted for me, it’s about ensuring that Americans can have faith in this election and in all future elections.” This task, he suggested, may prove to be his “single greatest achievement.”

Even after Trump’s presidency ends, that message will pave the way for GOP politicians and judges to further one of their party’s and the conservative movement’s most important ongoing projects: restricting voting rights. Trump lost this election, but he can still help Republicans win in the future.

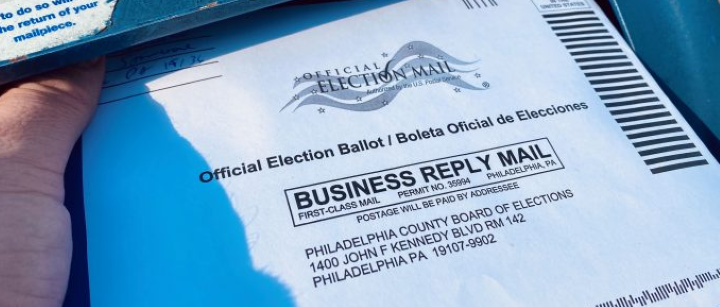

The 2020 election took place under an unprecedented set of circumstances, and in one sense, at least, it was an inarguable success: More than 150 million people voted in the middle of a deadly pandemic — the highest turnout in more than a century. More than 100 million people voted before Election Day; in Texas, early ballots surpassed the total number of ballots cast in 2016. In many states, largely pandemic-induced modifications to the voting process delivered a preview of what permanent changes to the status quo could look like: extended voter registration deadlines, expanded early voting periods and more access to safe and secure mail-in voting. On a nationwide scale, Americans saw firsthand, for the first time, that exercising their right to vote doesn’t have to be inconvenient.

If this level of participation becomes the norm, it could be disastrous for the Republican Party, which leans on a voter suppression regime meant to prune from the electorate voters whose exercise of the franchise tends to threaten Republican power and influence. Support for more onerous voter ID laws and voter roll purges has become a quasi-official plank of the party platform, often cast as an effort to protect American democracy from the exaggerated threat of voter fraud. (Occasionally, proponents acknowledge it as an anti-democratic political hardball tactic: Recall, in 2012, GOP leader of the Pennsylvania House Mike Turzai predicting that voter ID legislation would “allow Governor Romney to win the state” in that year’s presidential election.) In 2019, shortly before Democrats in the U.S. House passed H.R. 1, a bill that would have (among other things) streamlined voter registration and championed early voting, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.) penned a Washington Post op-ed ripping the legislation by dubbing it the “Democrat Politician Protection Act.”

If lawmakers permanently implement some of the measures that made 2020 a more user-friendly election, some in the GOP will look at it as an existential crisis. As Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.) put it in a November interview: “If Republicans don’t challenge and change the U.S. election system, there will never be another Republican president elected again.”

“To my Republican colleagues out there,” he added, “we have to fight back, or we will accept our fate.”

Many of his Republican colleagues appear to have drawn the same conclusion. In Washington state, which instituted universal vote-by-mail in 2011, a Republican lawmaker is now citing the experience of 2020 as evidence of the need to turn back the clock. “Washington has gotten off lucky for a decade,” said state Sen. Doug Ericksen. “But the disarray in other states this year ought to teach us that we are vulnerable, too.”

Elsewhere, Alabama’s lieutenant governor took to Twitter, vowing to “fight universal mail-in voting and no-excuse early voting,” calling it “an invitation for disaster, fraud, ballot-harvesting, confusion, and mayhem.” Former Wisconsin governor Scott Walker floated the idea of getting rid of no-excuse mail-in balloting, calling it a “huge problem” that is “only going to get worse going forward.” In a November op-ed, Republican National Committee Chair Ronna McDaniel denounced Democrats for “using the pandemic as an excuse” to modify election laws, framing her party’s multitudinous (and serially unsuccessful) legal challenges to the results of this year’s election as a fight for the “integrity of this and,” notably, “future elections.”

What these leaders recognize is that that the stakes of Trump’s voter fraud narrative are far higher than rescuing his failed reelection bid. If Democrats push for a new, improved version of H.R. 1 in the next Congress, Republicans will likely seek a principled-sounding narrative to argue for eliminating the pro-democracy rules that governed the 2020 election, and for making it harder for Americans to vote in 2022, 2024 and beyond. Pointing to recent allegations of fraud lingering in the political ether — allegations they put forward — could easily become a core part of this strategy. What appears, today, to be a stubborn refusal to acknowledge a tough loss could also lay the groundwork for a forthcoming ouroboros of voter-suppression rhetoric.

There’s precedent for this: As historian Rick Perlstein writes, in 1977 President Jimmy Carter proposed a landmark series of election reform bills, arguing that “millions of Americans are prevented or discouraged from voting in every election by antiquated and overly restrictive voter registration laws.” The Democrat’s agenda enjoyed bipartisan support until the political right leaped into action: The Heritage Foundation warned that Carter’s plan could enable “eight million illegal aliens” to vote, echoing the claims of former California governor-turned-conservative commentator Ronald Reagan, who had condemned mail-in voter registration for its “potential for cheating.” The package failed, and Reagan later defeated Carter in 1980’s landslide presidential election.

Forty years later, Republicans looking to their party’s future tried to run a version of the same playbook: Even in a pandemic, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott limited each county in his state to one mail-in ballot drop-box location, regardless of population; as a result, counties with only a few thousand residents had the same number of locations as Harris County (which overlaps with the city of Houston), the third-largest county in America. In Alabama, state officials prohibited counties from implementing curbside voting as a public safety measure. In Florida, less than a month before Election Day, the secretary of state’s office issued guidance that appeared to add additional requirements for county election officials to meet for setting up ballot drop-off locations.

Although these efforts weren’t enough to deliver Trump a victory, they didn’t go to waste, either: Last month, a Monmouth University poll found that 61 percent of Republicans were “not at all confident” that the election was conducted fairly and accurately and 70 percent of Republicans said Biden’s win was due to fraud. Last week, former GOP senator Rick Santorum predicted “a lot of action after this election to talk about these changes that we’ve made,” adding that “a lot of Republicans are actually cheering the president for bringing this to light so we can actually try to do something after this election is settled.” By pushing his voter fraud theories until the bitter end, Trump will leave his fellow Republicans with plenty of fodder to resist pro-democracy reforms well after he leaves office.