Female extremists in QAnon and ISIS are on the rise. We need a new strategy to combat them.

When President-elect Joe Biden takes office in January, he will face a shifting extremism landscape. Among the evolutions is the growing role of women in extremist groups, and the new commander-in-chief would be wise to take a fresh approach to this threat. Downplaying the phenomenon or misrepresenting what drives it, as so many previous administrations have done, will only make it worse.

With women constituting the majority of QAnon followers, we should not be surprised that more women are involved in plots of violence.

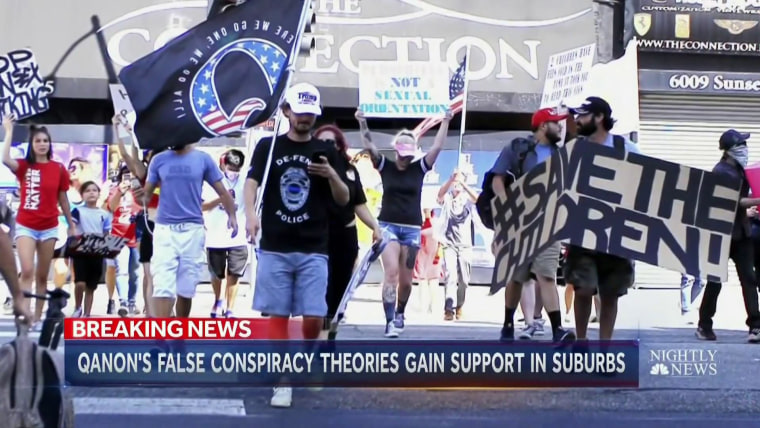

Take QAnon, which will be chief among the Biden national security team’s concerns.

The cultlike conspiracy movement believes President Donald Trump was divinely elected to save the world from a Satan-worshipping cabal of blood-drinking pedophiles that controls many in the media, Hollywood and the Democratic Party. QAnon will soon have a presence in Congress through newly elected Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and Lauren Boebert of Colorado.

Many of the acts of violence QAnon has inspired have been perpetrated by women. Most notably, Jessica Prim, a female QAnon supporter carrying a dozen knives, was arrested in May after authorities alleged that she had livestreamed her expedition to New York City to “take out” Biden. In Texas in August, another QAnon-supporting woman was charged with aggravated assault after, authorities alleged, she rammed her car into other people she believed were involved in the kidnapping of children.

With women constituting the majority of QAnon followers, we should not be surprised that more women are involved in plots of violence. And the disproportionate participation of women in QAnon is not accidental. QAnon, like the Islamic State militant group, understands that the best way to appeal to women is by exploiting their inherent altruism and desire to protect children.

While many far-right appeals to “save the white race” or “save individual liberties” have proven popular with angry or disillusioned young men, QAnon’s “save the children” narrative evokes a more visceral — even maternal — reaction among women. Both women accused of being QAnon attackers mentioned above were crying when they were arrested, the latter reported to have insisted that the intended victim “was a pedophile and had kidnapped a girl for human trafficking.” More generally, QAnon women are using social media with soft pastel hues to disseminate the conspiracy throughout North America and internationally.

This threat is not new, but it is increasing. And if we do not take a fresh approach to countering violent extremism by women, we will face only more terror. Until now, women in extremist movements have typically been portrayed as lacking agency. Lumped together with children, they are often perceived as having been manipulated into believing extremist ideologies and described as merely playing peripheral or support roles.

This has led to a situation in which we refuse to treat female terrorists with the same seriousness and concern with which we treat men. The skepticism has real impact on the ground. “Radicalized American women tend to commit the same types of crimes and have about the same success rate as radicalized men,” scholars Jamille Bigio and Rachel Vogelstein write. “Yet they are less likely to be arrested and convicted for terrorism-related crimes, highlighting a discrepancy in treatment and leaving a security threat unaddressed.”

Research has shown, for instance, that women returning to Western countries from ISIS areas are rarely prosecuted as severely as the men or serve any jail time whatsoever, meaning these women are free to be sources of radicalization for their communities.

In the past five years, ISIS has recruited unprecedented numbers of women — taking media and policy analysts by surprise. Using culturally curated age-appropriate narratives, their specialized marketing pitches were successful in appealing to Muslim teenagers and young adults throughout the Western world and beyond.

Similar to QAnon, ISIS targeted otherwise well-intentioned young women with positive messages about helping orphans whose parents had been killed by the brutal Assad regime in Syria. In one of the most deadly incidents, Tashfeen Malik, along with her husband, Syed Rizwan Farook, opened fire at a 2015 Christmas party in San Bernardino, California, killing 14 people. Investigations suggested that it was Malik who had radicalized her husband.

Western women have also been highly effective online recruiters for young girls from their countries of origin. Teenage girls — justifiably skittish about conversing with strange men online — are likely to be less circumspect about communicating with someone of the same gender who holds allure by being slightly older, sharing their interests and confidences and conveying a sense of inclusion. Thus Hoda Muthana from Alabama recruited American girls, while Aqsa Mahmood from Scotland successfully recruited girls from Great Britain.

The growing appeal of extremist ideologies to women and girls and the female-to-female luring tactics demonstrate that something has shifted in the ideological ecosystem around identity and belonging. This looming threat requires immediate attention, and curating approaches just for women is essential.

Indeed, trying to prevent young women and girls from being recruited means increasing counterterrorism officials’ knowledge about the psychology of belonging, agency and identity. It means having tailor-made programs that, for example, use former female recruiters. Unfortunately, policymakers are woefully behind the curve, still mostly seeing radical women as a curiosity and lumping all programs to counter violent extremism together rather than having science-driven solutions that are sensitive to gender.

This is a particularly stark omission given that the history of terrorism is rife with women, including one of the very first terrorists —Vera Zasulich, a member of Narodnaya Volya, the anarchist People’s Will — who attempted to assassinate the chief of police of St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1878. European terrorist groups in the 1960s and the 1970s were teeming with women, some even in positions of leadership.

Women have also played renowned roles in terrorist groups here in the United States. For instance, the Weather Underground, a 1970s-era far-left group responsible for a series of bombings, was co-founded by a woman.

More recent incidents on the far left demonstrate that the North American trend is not limited to QAnon. In September, a Canadian woman was arrested and accused of mailing ricin to Trump; later that month, a Black Lives Matter-affiliated activist was arrested after she drove a car into a crowd of counterprotesters. Most recently, two women were arrested in Washington state and accused of attempting to derail trains to oppose the construction of oil pipelines in solidarity with indigenous communities in Canada.

Though women internationally are estimated to be a third to more than half of all suicide bombers, such as 53 percent of suicide bombers for Nigeria’s Boko Haram, it is crucial to appreciate that women might be less visible in the U.S. but are nevertheless engaged behind the scenes. These roles have often not gotten the attention they warrant, as is the case with women in so many arenas, which affects funding for women-focused programs, research and policy formation to counter violent extremism.

As the country continues to fracture and political violence is seen more and more as a legitimate form of activism, acts of terrorism perpetrated by women are increasingly likely. Fortunately, our understanding of female terrorists has improved in recent years as more people study the phenomenon and journalists stop assuming that women lack agency.

We are far from prepared. We need to explore more fully the psychology of women who fight and from that consider specific counterterrorism measures.

Still, we are far from prepared. We need to explore more fully the psychology of women who fight and from that consider specific counterterrorism measures. These might include programs for middle school girls recognizing that girls and boys do not mature at the same age or absorb materials the same way, or the use of gaming platforms more popular with female players and thus useful in dissuading them from radicalization. We need to imagine the possibility of an all-female terrorist organization and whether it can pose threats that all-male armies do not.

In counterterrorism, we have a tendency to underestimate threats until they overrun the battlefield. The growing role of women in domestic terrorism is one of several emerging trends that policymakers, law enforcement and intelligence agencies much watch closely so we are not caught unaware once again.