Why people latch on to conspiracy theories, according to science

Insurgents swarmed the U.S. Capitol on January 6 to create chaos and defy legislators who had gathered to certify electoral votes. The presidential election, they say, was stolen—a belief encouraged by a powerful and trusted leader.

“They rigged an election,” President Donald Trump falsely claimed earlier that day to a crowd of thousands of supporters in Washington D.C. “Make no mistake, this election was stolen from you, from me, and from the country”

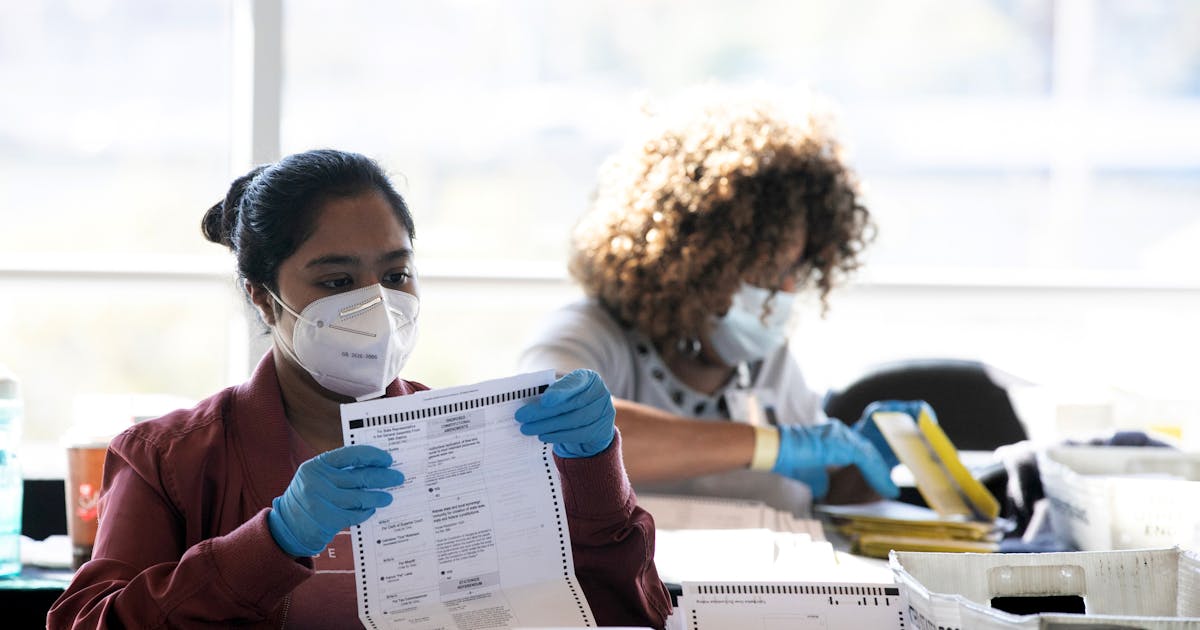

But the idea that the election was rigged is, by definition, a conspiracy theory—an explanation for events that relies on the assertion that powerful people are dishonestly manipulating society. In reality, dozens of lawsuits espousing accusations of voter fraud have been thrown out by state and federal courts. Attorney General William Barr said last month that the U.S. Justice Department has found no evidence of widespread voter fraud. Even Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell—a Republican ally of Trump through much of his presidency—recently called some of Trump’s voter fraud claims “sweeping conspiracy theories.”

Trump has “weaponized motivated reasoning,” says Peter Ditto, a social psychologist at the University of California, Irvine. He “incited a mob, and weaponized natural human tendencies.”

Those human tendencies—to believe whatever satisfies our preconceptions, whether true or not—were part of our lives long before rioters defiled the Capitol. And amid the pandemic, misinformation has seemingly run amuck.

The World Health Organization has called this moment an infodemic, a time in which a deluge of data is muddled with falsehoods, sometimes with devastating effects. A handful of people set 5G telecommunications towers ablaze after reading social media posts that alleged the new technology can cause COVID-19. A troubling minority have denied the existence of the virus, even as they lay dying from it.

Experts say that the majority of people do not easily fall for falsehoods. But when misinformation offers simple, casual explanations for otherwise random events, “it helps restore a sense of agency and control for many people,” says Sander van der Linden, a social psychologist at the University of Cambridge.

The misinformation constantly swirling around us is now set against the backdrop of the pandemic, an unemployment crisis, mass demonstrations against police violence and racial injustice, and a deeply polarizing presidential election. During times of turmoil, the explanations provided by conspiracy theories and other falsehoods can be even more appealing—though not impossible to discourage or resist.

The allure of conspiracies in a chaotic world

People use cognitive shortcuts—largely unconscious rules-of-thumb to make decisions faster—to determine what they should believe. And people experiencing anxiety or a sense of disorder, those who crave cognitive closure, may be even more reliant on those cognitive shortcuts to make sense of the world, says Marta Marchlewska, a social and political psychologist who studies conspiracy theories at the University of Warsaw in Poland.

A recent poll found that more than 50 percent of Americans reported increased stress during the pandemic. Amid the unease, “it’s not surprising that we are seeing a spike in conspiracy theories today,” says Karen Douglas, a social psychologist at the University of Kent in the England. Her research has found that people who feel insecure in their relationships and who tend to catastrophize life’s problems are more prone to believing in conspiracy theories.

Many of the conspiracy theories circulating today seek to explain the pandemic itself. A study published in October by van der Linden and colleagues presented residents from the U.S., U.K., Ireland, Spain, and Mexico with statements that contained common misinformation and facts about COVID-19.

While a large majority accurately identified misinformation, some people readily accepted the falsehoods. That includes between 22 and 37 percent of respondents (depending on the country) who believed the claim that the coronavirus was engineered in a laboratory in Wuhan, China. Some also decried accurate information as fake, such as the fact that diabetes increases your risk of severe illness from COVID-19.

The same participants who believed misinformation were also less likely to report that they complied with COVID-19 health guidance, such as wearing masks, and were more likely to express vaccine hesitancy. The finding supports a body of research that shows people’s willingness to believe fake news can have real behavioral effects, says Jan-Willem van Prooijen, a social psychologist at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Experts also say that people are more likely to believe misinformation that they are exposed to over and over again—such as allegations of election fraud or claims that COVID-19 is no more dangerous than the flu. “The brain mistakes familiarity for truth,” van der Linden says.

Collective narcissism

Another psychological factor that can lead to belief in conspiracies is what experts call “collective narcissism,” or a group’s inflated belief in its own significance. Marchlewska’s research suggests that collective narcissists are apt to look for imaginary enemies and adopt conspiracy explanations that blame them.

This urge is particularly strong when narcissistic people fail, or members of their group fail. “For some people, conspiracy beliefs are the best way to deal with the psychological threat posed by their failure,” Marchlewska says, adding that this phenomenon was likely at work as rioters stormed the Capitol.

One perceived enemy that President Trump and his supporters have frequently blamed is the media. “The media is the biggest problem we have, as far as I’m concerned,” Trump said to his supporters on January 6 before they marched to the Capitol. During the mayhem that followed, some of those supporters smashed media crews’ equipment, tied a camera cord into a noose, and scrawled “murder the media” on a door in the Capitol building.

By singling out an adversary who has “qualities that represent your own culturally influenced view of evil,” people can gain a sense of control over what’s happening to them, says Daniel Sullivan, a psychologist at the University of Arizona who studies how people cope with adverse life events.

People may also defend the viewpoints of groups they belong to on an even more instinctual level. Humans evolved in groups that competed with one another, sculpting our minds to be wary of outsiders and loyal to our factions, says Peter Ditto, a social psychologist at the University of California, Irvine. His 2019 study found that this kind of bias “is a natural and nearly ineradicable feature of human cognition.”

“I think the temptation is always to look at this as a clinical phenomenon—there’s something about those people,” Ditto says. “But your social surroundings can have a huge effect if you happen to be in a group with people who believe in something, or are mad about something.”

Follow the leader

While groups tend to share common beliefs, those beliefs are often sculpted by a handful of influential people. An October poll of more than 2,000 Americans conducted by Joseph Uscinski, an associate professor of political science at the University of Miami, found that what people believed was closely aligned with what they had been told by their political leaders. For example, 56 percent of people who identified as Democrats agreed that there was a conspiracy to stop the U.S. Post Office from processing mail-in ballots, compared to only 31 percent of Republicans.

People “who believe in conspiracy theories usually seek a savior—someone who will help them protect their in-group from conspiring enemies,” Marchlewska says. She points to QAnon, a conspiracy theory that proliferated online and falsely alleges a powerful group of Satanic pedophiles is plotting against President Trump. (A QAnon supporter, Marjorie Taylor Greene, recently won a House seat in Georgia.)

“There is no doubt that conspiracy theories and misinformation have been used by powerful figures over the ages,” Marchlewska says. “They serve as an extremely dangerous political weapon, helping manipulate the public to gain the power. First you search for imaginary enemies, then you prepare yourself for a fight. The final stage is usually tragic: You hurt innocent people.”

Identifying truth

Once people believe something, it can be almost impossible to dissuade them. Emily Thorson, a political scientist at Syracuse University, refers to this psychological phenomenon as belief echoes—an “obsessive, emotional response to information that can linger even after we know it’s false.”

When misinformation is covered in the news—often in an attempt to disprove falsehoods—the coverage can inadvertently aid in creating familiarity with incorrect beliefs. A recent study found this was especially true amid the pandemic, as media reports sometimes amplified the voices of people who “advocated unproven cures, denied what is known scientifically about the nature and origins of the novel SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, and proposed conspiracy theories which purport to explain causation and often allege nefarious intent.”

But experts say that educating people about the ways misinformation spreads can make a difference. In a recent study, van der Linden looked at whether pre-emptively warning people about the techniques that are used to spread falsehoods can help them gain immunity against fake news. He found that once people were warned about common misinformation techniques—including appealing to people’s emotions or expressing urgency in a message—participants were more likely to identify unreliable information.

Changing how often we are exposed to inaccuracies can also have an effect. Social media platforms—where misinformation can spread rapidly—are starting to experiment with removing unreliable posts. A 2019 study found that people trust mainstream news sources more than hyper-partisan or fake sites, which means social media platforms can help if they prioritize posts from credible sources, experts say.

When it comes to pandemic misinformation, personal relationships with doctors and other health experts can play a critical role. In a study published in September, Valerie Earnshaw, a social psychologist at the University of Delaware, found that those who believed in pandemic conspiracy theories were less likely to say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine—but 90 percent of the participants said they trusted their doctors. The finding adds to existing research showing doctors can help stymie the spread of health falsehoods directly.

As for convincing people the election was not rigged, “the most likely path to change will be for Republican leaders and other elites trusted by Donald Trump’s supporters to come out and make clear that they do not stand in line with him,” says Joseph A. Vitriol, a social and political psychologist at Stony Brook University in New York.

But overall, Vitriol says, society could benefit from the idea that it is OK to be wrong.

“People don’t like not knowing things, and often feel obliged to form opinions about things they don’t understand,” he says. To discourage people from clinging to false beliefs, we should encourage the idea that its “rational to change one’s mind in the face of new information.”