Majority of Detroiters and Blacks opposed to COVID-19 vaccine, rooted in racism

After the Rev. Charles Williams II got his first dose last month of the COVID-19 vaccine, some in his congregation at Historic King Solomon Baptist Church of Detroit were skeptical.

“People couldn’t believe that I took it,” said Williams, a civil rights advocate who leads the Michigan branch of the National Action Network. “They thought something is going to happen to me. … A lot of folks are still concerned.”

Some in his predominantly-Black church where Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. once gave noted talks, spun conspiracy theories to Williams and doubted that the vaccine was real. But he sought to reassure his congregation that the vaccine was safe and much needed, especially in areas like Detroit and African American communities that have been hit hardest by the coronavirus.

Many Blacks are wary and distrustful of the vaccine because of the damage that racism and implicit bias have historically caused Blacks, especially in the realm of health care. The Tuskegee Experiment still weighs on the mind of some.

“It’s going to take a lot of work to bring trust to the African American community around the issue of accepting a vaccine,” Williams said. “There’s a concern and people have a right to be concerned because of what we’ve seen happen in the past in regards to the history that African Americans have had with the health care industry.”

As the rate of vaccination is expected to increase in coming weeks, leaders and city officials are trying to encourage Detroiters, especially those in minority communities, to get vaccinated. They have a challenging task, surveys show.

In Detroit, which is 79% Black, 61% of residents said in an October survey by the University of Michigan they are unlikely to get a COVID-19 vaccine approved by the government when it becomes available.

Among Black residents in Detroit, 67% oppose getting a vaccine compared with only 31% of White residents, according to the University of Michigan’s Detroit Metro Area Communities Study. In Detroit, Blacks are four times as likely as Whites to say they don’t want to get the vaccine. Hispanics were twice as likely as Whites.

Nationally, there’s a similar pattern, with 58% of Black adults in a Pew Research Center survey in November saying they are less inclined to get vaccinated. People with lower incomes are also less likely.

“These racial and class differences are both disconcerting and yet completely understandable and unsurprising given the ways in which the health care system and government have systematically and historically underserved and mistreated poor people and people of color,” said Celeste Watkins-Hayes, a professor of public policy and sociology at the University of Michigan.

On Friday, Detroit Police Chief James Craig got vaccinated, encouraging Detroiters to get the vaccine. He noted that he was one of 500 employees of the Detroit Police Department to test positive for the coronavirus.

“In doing this, I hope this is an encouragement … to get the vaccine,” Craig said in a video from the Detroit Police Department. “The virus is real, it’s still alive and well. This is a great first step. This is a way to save lives and reduce the spread.”

The Rev. Jesse Jackson also got vaccinated on Friday in a public event designed to encourage African Americans to get the vaccine, reported Chicago media outlets. Jackson was accompanied by Dr. Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett, a scientist who is Black and helped lead the team that developed Moderna’s vaccine.

Williams of Detroit noted Corbett’s involvement as one reason he trusts the vaccine.

“There are a couple of things that really make me more comfortable,” Williams said. “One of the young ladies who helped develop the vaccine, Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, is a member of the Black church in Dallas, Texas. She’s one of the key crafters of the design of the vaccine — that makes me a lot more comfortable.”

Williams says that Blacks will be shut out of the recovery if they don’t take the vaccine. “I don’t want to be left behind and I don’t want people in my community to be left behind because of the fear of getting COVID-19 once the world starts back up again,” Williams said.

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan spoke about the challenges of persuading Detroiters to get vaccinated in a news conference broadcast online last month.

“We can’t have a conversation about whether to take a vaccine from the federal government without acknowledging the history of racism that we have had in the health care system,” Duggan said Dec. 22.

“The Tuskegee experiment wasn’t done by some private lab,” Duggan said, referring to a 40-year study of Black men done by the U.S. government that led to some dying of untreated illness. “It was conducted by the U.S. public health service and the CDC. It wasn’t ancient history. The Tuskegee experiments ran until the 1970s and the federal government made an absolutely shameful decision to tell poor African Americans they were being treated for syphilis when they weren’t in order to look at the symptoms. And it wasn’t until 1997 that a president finally acknowledged it and spoke out and apologized for this despicable period of history.”

Related: Health and race disparities in America have deep roots: A brief timeline

Henry Ford Health System President and CEO Wright Lassiter, who is Black, also spoke of “the concern and the potential trust issues that exist in communities like Detroit and communities of color.”

“I was born in Tuskegee, Alabama,” Lassiter said. “And so I’m really familiar with issues in that community and with issues of trust and distrust in the African American community. One of the reasons I’m here is to serve as an example for … African Americans in our state, this region, and in the city, to let them know that I feel very confident in both the safety and efficacy of this vaccine.”

On Thursday, Duggan announced plans to use TCF Center in Detroit as a vaccination site and working with churches and ministers to get the word out.

Minorities needed for clinical trials

The distrust among many Black Americans has also been seen in the challenges in getting them to participate in large numbers in COVID-19 clinical trials, USA Today reported in October. The first two trials included about 3,000 Black participants each, but it wasn’t easy.

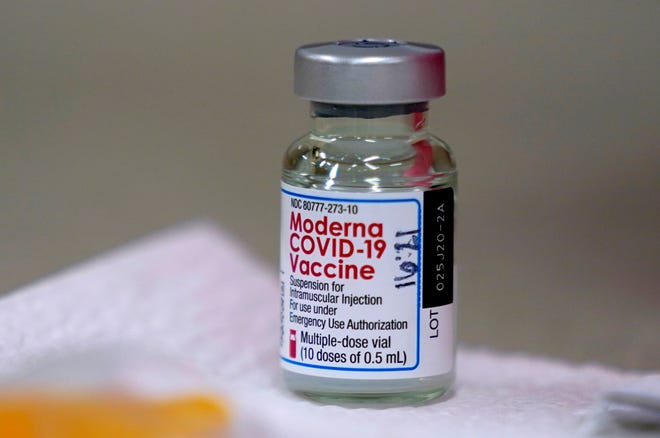

Moderna, one of the companies developing a leading COVID-19 vaccine, slowed its clinical trial in September to boost the number of minority participants.

“This was sustained and difficult work,” company president Stephen Hoge said in an October phone interview. “This was not something I’m aware of anyone doing before.”

Without adequate Black and Hispanic participation in clinical trials, it won’t be clear whether the vaccine will be safe and effective for them.

The company tried a number of different approaches, beginning shortly after the trial launched at the end of July, but the effort really took off in the fall, he said. “The last five-six weeks have been a daily grind to build the study we think we needed to provide for confidence.”

Now fully enrolled, the study includes 3,000 Black participants, 10% of the total, and about twice that many Hispanic volunteers. With about 36% of enrollees of color, Hoge said the study is representative of the diversity of the United States.

“People should have confidence in those communities that if the vaccine works in that sample, that they will derive benefit from it as well,” Hoge said.

Detroit and state start mass vaccinations

Duggan on Thursday announced the city’s plans in coming weeks to vaccinate Detroiters, focusing first on vulnerable populations such as senior citizens and homeless people.

He said there are about 500,000 adults in Detroit.

Out of those, “based on our surveys, probably 40% would like a vaccine tomorrow,” about 200,000 people, Duggan said during a news conference broadcast online.

Another “40% of Detroiters think they should get it, but they don’t want to be in the first wave,” Duggan said. “And about 20% are never going to get it because they don’t just trust anything’s been said.”

“For the 200,000 that want it tomorrow, we are going to everyone really hard to get those folks in.”

The state of Michigan is also reaching out to minority communities, developing a media campaign targeting minority groups, especially African Americans, said Lynn Sutfin, spokesman for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

“The paid media campaign will cover radio, TV, social media, amplified editorial content and targeted digital,” Sutfin told the Free Press. “A large portion of the media will be focused specifically on stations that reach minority audiences, especially African Americans. In addition, we’ve created specific segments and messaging to reach our most vulnerable populations who are hesitant to get vaccinated.”

The state “is committed to vaccinating 70% of Michiganders over age 16 by the end of 2121,” Sutfin said. “This includes our most vulnerable populations in the state. We are reaching out to communities with both earned and paid media. … One of the most important components of our research, included getting feedback from residents through focus groups, which included African American, Hispanic, Caucasian and Arab American adults of all ages. The objective was to be sure messaging developed resonated with these audiences in responding to vaccine hesitancy.”

Williams said the 95% and 94.5% success rate of the vaccines is another reason he supports them. He will get his second dose next week in Ann Arbor.

As a member of the clergy who often interacts with patients in hospital settings and in his church, he was able to qualify to get an early vaccine. He said that some church members are still reluctant to get the vaccine, floating discredited conspiracy theories seen online. Williams hopes to convince them it’s safe.

“There’s no vaccine that has those kind of numbers,” Williams said of the 95% effiacy rates. “We’re really making ourselves super safe when we take the vaccine. I’m telling my family members and I’m telling my church members, and I’m telling my community that this is important, to save our community from this deadly virus.”

USA Today reporter Karen Weintraub contributed to this report.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

Contact Niraj Warikoo:nwarikoo@freepress.com or 313-223-4792. Twitter @nwarikoo

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Detroit Free Press can be found here ***