Congressional Aid for COVID Victims Takes Lessons from Parliament’s Stingy Aid to Irish in the Great Famine of the 1840s

The parallel of the American economic landscape from COVID’s deathly sweep seems far more like Ireland’s in the great potato famine of 1845-52 than the Great Depression of the 1930s. And the stinginess and indifference by the upper classes ruling both countries to the suffering of those considered far beneath them—who always take the brunt of most catastrophes—in both countries has not changed an iota.

In Ireland, a million died of starvation or from famine’s complications, bodies rotting where they fell. Nearly two million fled the country, most heading for the U.S. In America today, nearly 400,000 deaths from the pandemic are projected by year’s end Hundreds of unclaimed bodies are in refrigerator trucks (maximum storage: 50 each ) awaiting mass burials.

Most destitute Americans in the 1930s did indeed have a champion in president Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) whose first priority the day after his inauguration on March 4, 1933 was their long and short-term recoveries. He issued 103 Executive Orders (EO) between March and June, mostly for New Deal programs covering unemployment, healthcare, housing, and food supplies.

Unfortunately, neither the 99 percenters of today nor those in Ireland then (and now) have had such a practical, tough, and caring leader who did yeoman’s work to put them back on their feet. The disasters made the populace totally dependent on upper-class decisions in Parliament then and Congress now about their fate. And the decisions in both cases were to employ the “herd immunity” policy of doing almost nothing—especially spending tax monies the stricken themselves provide over the years—to avoid deaths and long-term ailments of hundreds of thousands of ordinary people, the “commons.”

Ireland in the 1840s did have representation in Parliament (105 in the House of Commons, 28 titled landowners in Lords). Congress today has 100 members in the Senate, 435 in House. Serving in both bodies has required either wealth or influential donors and time away from businesses and professions—and travel expenses.

So in today’s Congress, half its members are millionaires—as are those currently in the Irish Parliament. They move in elevated political and social circles. They also have enviable “perks” in transportation, dining, newsletter mailings, and the like.

With wealth, power, prestige, and perks, how could lawmakers possibly identify with victims of the famine or COVID or the urgency of relief measures? Besides, why would need for immediate help be considered if survivors could not (or would not) vote, and had yet to complain about their “taxation without representation?”

In both calamities, most affected have been either unaware of—or feel powerless about—legislative life-and-death decisions impacting them made in London or Washington, D.C. Judging from rulers’ inactions in both crises, most of those ruled have always believed they can do little to oppose leaders’ critical decisions supported by courts and armies—until millions form powerful movements and take appropriate actions. And today with the Internet—unlike radio and television requiring advertising money—it is the easiest way to connect millions of the commons than in any other time in history.

In practice, most people have been unaware of what is being designed in secret unless in modern times a trial balloon has been floated to test reactions. Both the Irish then and Americans up to recently usually have been presented with a fait accompli and must swallow it. But many refused. In Ireland it meant decades of guerrilla warfare against the British. Americans went for massive marches and placards on one hand and militant strike action on the other.

In this year’s five COVID relief bills, for example, no public hearings were held, nor were wanted by Congress. Members’ cynical presumption was that constituents could always use emails, calls, and town halls to provide their representatives—and advisors and legislative aides—with feedback. They knew the most affected had neither the time nor inclination to provide input.

Hearings indeed would have slowed down dispatching emergency aid even for the two successful bills, but it has taken nine months for them to be signed into law. The last—Coronavirus Response Additional Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020 —passed because it was bundled with a vital $1.4 trillion bill to keep government operations running until September.

With typical upper-class disregard for the hardships of commoners impacted by economic disasters, Trump used a sadistic Sunday signing prank that cost more than 14 million a week of unemployment checks out of the 11 weeks before the March 14 permanent cutoff. But, then, three years ago he’d tossed paper towels as mop-up relief for Puerto Rico’s desperate survivors of Hurricane Maria. At least when an equally disdainful, yet frightened, Queen Victoria was finally persuaded to make a state visit to Ireland in 1849 when famine was ebbing, she donated £2,000 for relief.

Sadly, only a sprinkling of highly vocal populist legislative members—Prime Minister Robert Peel to an extent and Sen. Bernie Sanders —have fought for legislative measures to provide genuine long-term solutions to adversities suffered by the lower classes. But most members in both eras have treated them with the same indifference and particular cruelty by control of the public purse.

In Ireland, famine relief of the mid-1840s and early 1850s entailed free soup kitchens, a few pence per day on public-work jobs, or the workhouse. In 1847, the head of Britain’s relief operations for Ireland was the penny-pinching Sir Randolph Routh . He regarded the Irish as lazy and full of “all kinds of vice,” and was delighted to report:

The soup [kitchen] system promises to be a great resource and I am endeavouring to turn the views of the Committees to it. It will have a double effect of feeding the people at a lower price and economising our meal.

His counterpart of today, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) (2018 net worth: $39.2 million ), just voted to appropriate without question some $740 billion to the Pentagon for FY2021. Yet two weeks later, he opposed giving any money for millions of COVID victims provided in the just-passed bipartisan economic stimulus bill (H.R. 133, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 ). His rationale was:

While I am glad a government shutdown was avoided and that financial relief will finally reach many who truly need it, the fact that this dysfunction has become routine is the reason we are currently $27.5 trillion in debt. This combined spending bill will drive our debt to over $29 trillion by the end of this fiscal year….We do not have an unlimited checking account. We must spend federal dollars, money we are borrowing from future generations, more carefully and place limits on how much we are mortgaging our children’s future.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has repeatedly blasted their upper-class view:

When it comes to tax breaks for rich people or corporate welfare or bloated military budgets, that’s OK. But when you stand up and you say that working-class families need some help, ‘Oh my God, the world is gonna collapse.’ So I am a little bit tired of that hypocrisy.

In both Parliament then and Congress now, a few members might have felt a twinge of guilt about that hypocrisy of their parsimonious actions—but not many. Most have been extremely grateful not to be among the millions facing a bitterly cold winter of discontent and despair over joblessness, homelessness, starvation—and death by famine or COVID.

Trying to provide relief and recovery to the victims of sudden Acts of Nature or financial crashes in both countries is perhaps the greatest illustration of class warfare. Most decision makers in Parliament and Congress have always had low regard for bankrupts and beggars as the “undeserving poor,” “layabouts,” or “welfare queens” bent on stealing taxpayer money (before they do).

Parliament passed only two relief laws for the Irish during the famine, both in 1847—the Destitute Poor Act and the Poor Law Extension Act . Total expense was £8 million of which £7 million came from Irish taxes and £1 from Ireland’s landlords.

The first set up those soup kitchens which were to feed three million . The second law limited borrowers to local lenders. Unlike today’s COVID relief laws, neither major businesses, institutions nor financial houses were included in those laws.

Not so for Congress in the two of five COVID relief bills it finally passed this year.

In the first place, the bipartisan, Scrooge-like leaders never would have produced, much less passed, a stand-alone rescue bill solely for COVID’s jobless to pay their rent, utilities, food, and doctor bills. This was just shown by Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) blocking passage of a stand-alone House-passed bill for a one-time $2,000 stimulus check for most households. It was to replace the $600 allotted in the $900 billion Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 which Trump signed into law December 22.

Nor were they about to produce a stand-alone bill devoted solely to bailing out businesses and institutions. The 2011 Occupy movement notoriously identified the class system as the 1 percent rich against the 99 percent of most Americans. Our street demonstrators’ famous chant was “Banks Got Bailed Out/We Got Sold Out.” Greed suddenly got a bad name and might cost incumbents in the upcoming elections.

The solution was to combine both people and business-rescue operations and tout relief measures and hide greed. In the first relief bill, the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security), more than half of the initial funds were bailouts to corporations and tax-extension breaks for the wealthy and other sources dimly related to relief for people.

That some of these allocations—later omitted by adverse publicity—were even included reflects on lawmakers’ pandemic priorities. Among them: $696 billion for the Pentagon; $105 billion to support mostly higher education; $7 billion to expand broadband internet access; $6.3 billion in tax deductions for business meals; $2.5 billion for NASCAR race tracks; $1.86 billion for a new FBI building; $1.5 billion for NASA; $1.5 billion for substance abuse prevention/treatment; $1.45 billion for at least two hospital ships; $1.4 billion for Trump’s border wall; $200 million for timber harvesting; and a permanent excise tax cut for producers of beer, wine, distilled spirits.

One infamous provision—the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)—initially was allocated $349 billion in the CARES Act; today, it’s $285 billion. It involved forgivable million-dollar loans supposedly to smallbusinesses by the SBA (Small Business Administration) to cover employee wages until reopenings. But major corporations and institutions—some unaffected by COVID—were first in line siphoned off a lion’s share of the loan funds until complaints by enough small businesses were addressed. Too, because SBA loans are made through approved lenders such JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, etc. they charged that agency with 1-5 percent “processing fees” (PC), depending on the loan’s size. And have made billions. For instance, a 5 percent PC on an average loan of, say, $104,760 borrowed by 280,185 small businesses, the profit would be $1.5 billion.

As the nine months passed, COVID’s hardest-hit, the working-class, got less and less while COVID continued to decimate the population.

The first bill, the nearly $4 trillion CARES Act whipped through Congress to Trump’s signature in seven days by March 27. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin withheld nearly $500 billion from the people’s portion to invest it into businesses.

Provisions included a one-time, Trump-autographed $1,200 check to 159 million families to “stimulate” spending, and a weekly $600 supplement to unemployment checks ending the day after Christmas. “Forbearance” was offered for student-loan payments and moratoriums for rent and mortgage payments—but only until December 31.

So legislative aides slogged back to the drawing board once more after a group of bipartisan House members asked for a $908 billion relief bill to avoid a howling outcry by recipients when all benefits ended. The final draft was whittled down to $900 billion .

Its 5,593 pages included a one-time stimulus check of $600 for each family member to those earning lessthan $75,000 a year, an extension for unemployment checks until March 14 with the $600 supplement cut to $300 per week, and another extension for paid sick and family leave until March 31. Homeowners with federal mortgages requesting forbearance would have a 90-day extension on foreclosures. Renters in federally subsidized housing were given a 120-day moratorium without penalties. Eviction moratoriums would last only until January 31. As for student loans, none were offered because lawmakers decided nine months of forbearance until January 31 was sufficient.

Even with these cutbacks and brief extensions, key Republicans like South Dakota’s Sen. John Thune (net worth: $384,509.50 ) opposed including that stimulus check to the unemployed. Combined with their weekly unemployment check, that would be double-dipping, he believed.

Meantime in today’s Ireland, equally hard hit by COVID and meager relief measures, the February elections resulted in a three-party coalition government—two for the upper classes and the fast-growing working-class party, Sinn Fein. The country’s FY2021 budget of $133.8 billion may have had a line-item of $1.5 billion for the military, but, as in the U.S., its COVID relief got so few additional crumbs from 2020, that Sinn Fein’s finance spokesperson snapped that for ordinary workers and families the allocation was: “crumbs off the table—there’s nothing for renters, people on social welfare or pensioners and nothing in terms of childcare.” By May, Ireland had at least a million jobless receiving a weekly $390 unemployment check. In the U.S., it was 20.3 million Americans by November whose benefits averaged $319 weekly .

As financial columnist Nick Beams summed up the reality of the class system’s centuries-old appallingly cruel treatment of the commons in this Armageddon:

When governments and central banks launched their multi-trillion-dollar bailout operations, they claimed the extraordinary measures were necessary to save the economy. This fraud has been exposed. The sole concern of the ruling oligarchy was not the health and economic well-being of the mass of the population, but that of the financial markets.

Both our countries have similar histories and scrappy lower classes. We both fought Britain for Independence and experienced heavy immigration, millions to America mostly from Europe, 500,000 fleeing the Great Famine to the same destination. We’ve had civil wars—racial in the U.S., religious in Ireland—and were leveled economically by the Great Depression. And now we 99 percenters share COVID’s ongoing horrors, one of which is that millions commoners will be the last class even in the “rich countries” to receive the vaccine. After all, its producers can make only so many in a day.

But it’s a certainty that after the healthcare professionals are inoculated, the rich will be next in the distribution line.

New administrations in both countries are facing monumental financial challenges to their COVID-affected populations. And their major challenge seems to be how to find the revenues to cover those domestic expenditures without heavy taxation on the wealthy or corporations or forcing austerity on those who can least afford it. From a historical perspective, the wealthy majority in the Irish Parliament and Congress are not about to tax the rich to give relief to the poor until they have first wrung the last penny from the commons.

Columnist Shane O’Brien with the Irishcentral website speculated that raising revenue in Ireland might be done by taxing private pension savings. Or a progressive tax for bank accounts over £10,000. Or increasing property taxes and “asset tax structures” on the wealthy. But given the difficulty of even collecting taxes on the wealthy and corporations, both the Irish Parliament and Congress may begin to talk about “bail-ins” wherein the government seizes portions of bank accounts to avoid going bankrupt—with crisp documents vowing to return every penny—some day. Perhaps that’s what it will take to arouse the ruled in both countries against the rulers. As poet Edwin Markham warned in 1899, America’s “gilded age”:

O masters, lords and rulers in all lands

How will the Future reckon with this Man?

How answer his brute question in that hour

When whirlwinds of rebellion shake all shores?…. After the silence of the centuries?

The January 6 invasion and desecration of our nation’s Capitol is but a sample of what’s ahead in every state capitol if nothing changes for ordinary Americans by Congress.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Barbara G. Ellis, Ph.D., is the principal of a Portland (OR) writing firm. A veteran professional writer and editor (LIFE magazine, Washington, D.C. Evening Star, Beirut Daily Star, Mideast Magazine), she also was a journalism professor (Oregon State University/Louisiana’s McNeese State University). Author of dozens of articles for magazines and online websites, she was a nominee for the 2004 Pulitzer Prize in history (The Moving Appeal). Today, she contributes to Truthout and Counterpunch, RSN, DissidentVoice, Global Research, and OpEdNews, as well as being a political and environmental activist.

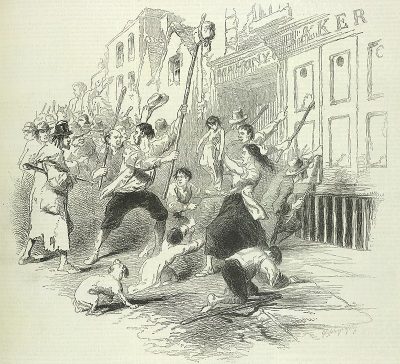

Featured image: Rioters in Dungarvan attempt to break into a bakery; the poor could not afford to buy what food was available. (The Pictorial Times, 1846). (CC0)

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Global Research can be found here ***