Tips for helping people leave QAnon, white supremacist groups

Scott Hancock has been challenging Confederate sympathizers for five years. But in 2020, he said something changed.

“It was the first time I wondered if I could actually get hurt,” said Hancock, an associate professor of history and Africana Studies at Gettysburg College.

Hancock, who is Black, had made a practice of going to the Civil War-era battlefields near the college once or twice a year when he knew there would be an event to glorify the Confederacy. He and family or friends would show up with signs situating Confederate leaders in “a better, historically grounded reality,” and each time a few people would engage on the role of slavery in the war.

“Usually they’ll say things like, you know, ‘it was states rights,’” he said. In response, Hancock would bring up historic declarations by Confederate leaders. For example, “The Confederate Constitution says … negro slavery will be protected,” he said.

Such interactions felt safe, and occasionally productive, until 2020. Things changed on the Fourth of July when Hancock was near a monument to Virginia’s soldiers. Armed men hurled racial epithets, followed Hancock and his friends as they tried to leave, and took pictures of their license plates.

“The only free speech they were interested in was their own,” he said. This time, no one wanted to talk with him about history.

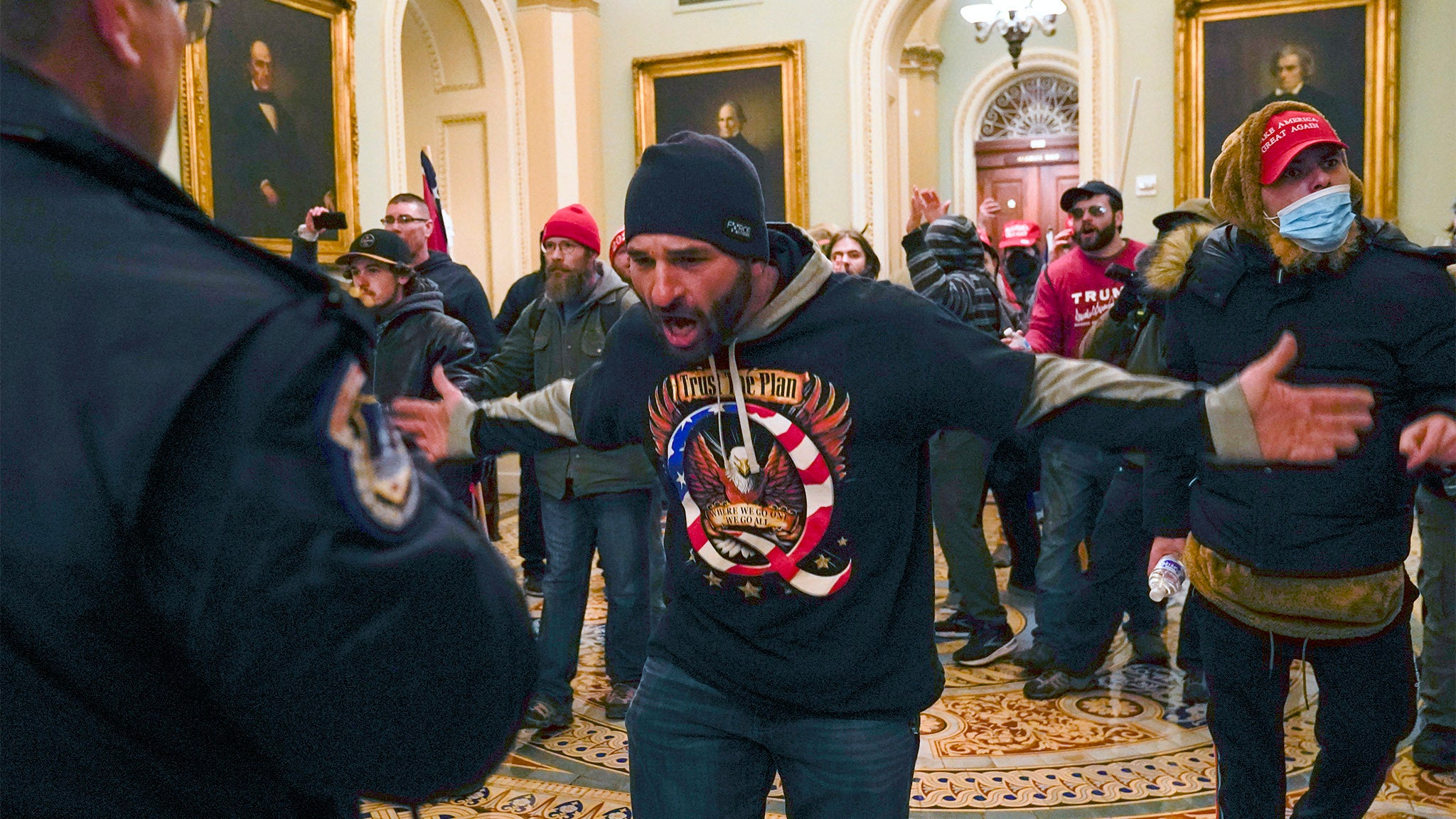

After supporters of President Donald Trump led a violent insurrection of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, Hancock began viewing his work in a new light, questioning his methods, and wondering the best way to “engage with someone who says and does things you profoundly disagree with,” he said.

It’s a feeling people across the country are grappling with — as some were shocked to see their friends, co-workers, or even parents participating in the Capitol riot.

That deadly event, like the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville in 2017, will most likely lead to an uptick in radicalization, according to Dimitrios Kalantzis, a spokesperson with Life After Hate, a nonprofit that helps people leave far-right hate groups..

Keystone Crossroads has heard many examples of families pulled apart by polarization in the last several years. Here are what some experts say about why that’s happening, and what friends, family members, and bystanders can try to do about it.

‘A social process’

Leading up to the violent siege in D.C., months of smaller armed protests occurred around Pennsylvania.

In April, armed men in a former military vehicle rolled through Harrisburg during a protest over COVID-19 shutdown orders.

In July, a false rumor that “Antifa” members were heading to Gettysburg for Independence Day drew armed counterprotesters, the same ones who harassed Hancock and his friends.

In November, Trump supporters camped outside of the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia, where votes were being tallied, to lob false accusations of voter fraud. Two armed men who drove up from Virginia to allegedly interfere with the ballot-counting operation were charged with election-related crimes.

At the “Stop the Steal” rally on Jan. 6, overlapping groups of Trump supporters converged: diehard fans of the outgoing president, anti-government extremists, white supremacists, and believers in the baseless QAnon conspiracy theory.

While “virtually all violent vanguard elements appeared to come from predominantly far-right, fringe groups,” according to a report from the Network Contagion Research Institution, extremism experts say the combination of mainstream GOP voters and fringe extremists is cause for deep concern.

That’s because “radicalization is a very social process,” said Brian Hughes, associate director of the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab at American University.

“When you have people who are not yet radicalized, who are only considering extremist ideas but haven’t committed to them yet, when they’re able to mix socially with real extremists, people who are fully radicalized, it accelerates the process,” Hughes continued.

Research he contributed to on the threat posed by QAnon, which falsely posits the Democratic Party is run by pedophiles, has shown that entrants into that group become radicalized “much more [rapidly] than that of other cults and extremist groups.” It also found the group has evolved to become more militant over time, and since 2019 the Department of Homeland Security has considered the group a domestic terror threat.

Social media gave people the opportunity to mix with people from adjacent, but different, extremist groups easily. Then, a global pandemic further isolated people in their homes, often inside their own information bubbles.

“We just set up the entire country in a stressful situation,” said Audrey Alexander, a researcher and instructor at West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center. As the pandemic reordered society and isolated individuals, she fears it may have also contributed to mass radicalization.

How to: Before, during, and after deep radicalization

When talking to someone who is toying with extremist ideas, there can be a tendency to fight over facts and ideology. But research shows that doesn’t work.

Recognizing the characteristics of who is likely to be pushed to extremist views, and inoculating people before they get radicalized, can work.

Experts say there are certain “on-ramps,” or risk factors, to joining a movement with violent ideology. For example, paths to QAnon may be a pre-existing interest in wellness movements that are skeptical of science, or anxiety around parenting.

“Some parents will project their anxieties over parenthood and their children’s future onto fantasies such as those provided by QAnon,” which involve protecting children from pedophilia, according to a report by NCRI.

Another risk factor is the fear of losing social or economic status. There isn’t a connection between poverty and extremism, but there is a connection to downward mobility, said Hughes.

“It has to do with disappointed expectations, much more than material lack,” he said. “They feel as though they’ve been robbed of something and are looking for someone to blame.”

Before they find someone to blame, one way to prevent someone from becoming a follower of a radical ideology is to expose them to the techniques that will be used to manipulate them.

The same way a parent might warn their teenager that credit card companies will try all sorts of inducements to get them to take out a card and accrue debt once they turn 18, letting people know about how QAnon tries to recruit new followers to their worldview can keep them from becoming one.

For example, QAnon adherents will often append their claims with the line “do your own research.”

While seemingly benign, Hughes said the phrase is a red flag, a sign that the writer has an ulterior motive. “The idea is that you do your own research to reach the conclusion that they’ve already offered you,” he said.

By letting someone know that phrase is not an actual invitation to learn, but a way of enticing them down a rabbit hole of disinformation, you can stop them from taking that path.

Hughes said one way to deliver that warning is saying, “If you see someone making an outlandish claim … and instead of supporting it [with evidence, the person] says, ‘Do your own research and you’ll see what I mean,’ that means this person is almost certainly trying to manipulate you.”

Once warned, people tend to get mad and reject the ploy, he said. Trying to counter the outlandish claim with facts does not work, and simply lends it more credibility.

Once someone starts to become radicalized, there are also tools to pull them back.

The first rule is “never mock or ridicule a person,” said Hughes. “This has a demonstrated effect of reinforcing a delusional belief.” Instead, be positive and proactive and attempt to keep the loved one linked to the real world.

The second is “don’t cancel your relationship,” said Dimitrios Kalantzis, director of communications with Life After Hate. The group also has materials for family members of white supremacists.

As with inoculation, talking about the content of the hateful ideology doesn’t really help, he said, even if you’d rather be refuting anti-Semitic, misogynist, or racist rhetoric. What works is exploring what that ideology offers the person.

“They’re not doing it by accident. They’re doing it because it’s providing something,” said Kalantzis. Former extremists have shared that belonging to an extremist group made them feel like they mattered. Reinforcing that someone belongs, whether it’s in a family or other group, can help diffuse some of the appeal of extremist ideology.

Researchers say another best practice is not reducing someone’s entire personality to their political ideology — that is, writing someone off as a “MAGA person” or only engaging with their involvement in QAnon. That reinforces that they only have an identity as a part of a radicalized group.

Finally, if you can, get the person away from the things that trigger further radicalization, namely the internet.

“The same way you would throw out an alcoholic’s liquor cabinet, try to get them off of social media,” said Hughes.

People who are hardcore — for example, a family member who is part of a militia — “are extremely difficult to reach,” said Hughes. In that case, the advice changes. If talking it through does not work, there need to be consequences, according to Hughes. “You have to disengage with love,” he explained, and leave the door open for support for the day the person chooses to leave.

Because many violent ideological groups are abusive themselves, the brotherhood and love that these groups promise are superficial. To get them to leave, they need to believe they have another community that will support them, according to the researcher.

While all of these methods presume a relationship, there is also one technique with some scientific backing that works even among total strangers: deep canvassing. That means talking about a hot-button issue, such as immigration or transgender rights, without judgment and through personal narratives, instead of arguing points of fact.

That’s a good reminder for Scott Henderson, the Gettysburg College historian who engages new people on the battlefields.

“When we do this and go out, this is about people,” he said. “Not about a cause.”

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from WHYY can be found here ***