Is ‘The Great Reset’ a plan of the global elites to restrict our freedoms?

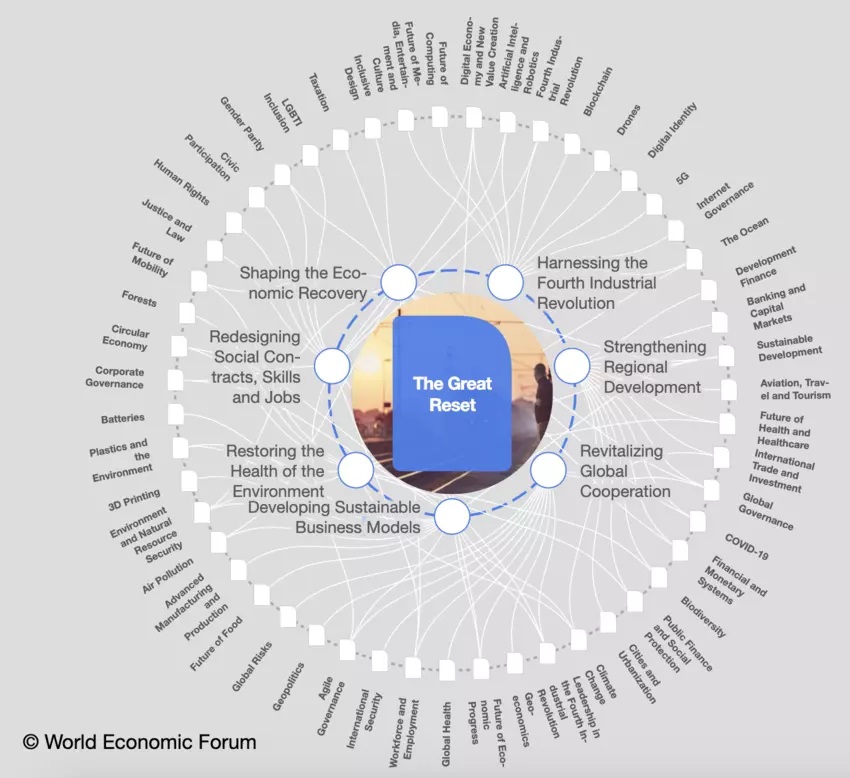

The Great Reset is the newest initiative of the World Economic Forum (WEF, also known just as ‘Davos’) and will be launched during a 4-day online conference in January 2021.

But some of the ideas of this global platform (that over that las 50 years has brought together in Switzerland political leaders, CEOs of large companies, and well-known philanthropists) were made public in the last months. The first reactions of some voices around the globe to the initiative has been of strong criticism and suspicion.

Is this global agenda an attempt to restrict the national sovereignty of countries? Will the efforts to respond to global challenges such as the environmental crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic lead to further control over the movements of the population? Is the WEF part of a larger-scale plan to impose ideological programmes worldwide in key areas such as education and economy?

These and other questions are receiving a resounding “yes” in some online forums, social media and podcasts of commentators.

But how does the WEF explain its plan? German Klaus Schwab is the founder and Executive Director of the World Economic Forum and the main promoter of The Great Reset.

“There are many reasons to pursue a Great Reset, but the most urgent is COVID-19”, he wrote in spring 2020 as he presented the initiative. “The world must act jointly and swiftly to revamp all aspects of our societies and economies, from education to social contracts and working conditions. Every country, from the United States to China, must participate, and every industry, from oil and gas to tech, must be transformed. In short, we need a Great Reset of capitalism”.

As he summarised some of the crises that are perceived worldwide, he comes to the conclusion that there is an opportunity to “dream” with a large change: “Clearly, the will to build a better society does exist. We must use it to secure the Great Reset that we so badly need. That will require stronger and more effective governments, though this does not imply an ideological push for bigger ones. And it will demand private-sector engagement every step of the way”.

According to Schwab, concepts that should be central in the global action of governments, companies, universities and human rights activists in the next years should include: efforts to guarantee full equality in all areas of society, making sure that the “Fourth Industrial Revolution supports the public good”, reforming capitalism by creating a “stakeholder economy”, and building “green cities”.

The pandemic, the leader of the WEF says, has become “a rare but narrow window of opportunity to reflect, reimagine, and reset our world to create a healthier, more equitable, and more prosperous future”.

In short, the plan aims to “build a new social contract that honours the dignity of every human being” that fits into the United Nations 2030 Global Development Goals.

Among those who have strongly reacted to the WEF’s initiative is a Canadian parliamentarian and former minister, Pierre Poilievre. In November, he said: “Canadians must defend themselves against the global elites who feed on the fears and desperation of the people in order to impose their seizure of power”. An online petition he started to “stop the great reset” was supported by over 80,000 people in only three days.

Peruvian economist Miklos Lukacs has also often spoken about The Great Reset. In a video viewed over 1 million times, he speaks of the role of policy makers such the European Union and China. The ideologists of these efforts to restrict the rights of the population would be “progressive philanthropists” like George Soros, who are “buying the political support” of world leaders to “set the foundations of technological dystopia”. According to Lukacs, an increasing “verticalization of politics” is leading to a sort of global “techno-collectivist tyranny”.

US economist and declared anti-Marxist Justin Haskins has also claimed that key politicians are involved in the hidden agenda of Davos. “There is a dangerous threat to freedom brewing, (…) the ‘Great Reset’, and it is rapidly gaining popularity among many of the world’s most powerful movers and shakers, including U.S. business and political leaders like Al Gore and John Kerry”, he said. The WEF initiative aims to “completely destroy the global capitalist economy and reform the Western world”.

As Google statistics show, the online searches of the term “Great Reset” peaked in November.

One of the most shared voices outside the US is Carlo Maria Viganò, an Italian retired Roman Catholic bishop, who in open letters to Pope Francis has claimed The Great Reset was being promoted by Bill Gates and other members of “a global elite that wants to subdue all of humanity, imposing coercive measures with which to drastically limit individual freedoms”.

English writer James Delingpole of Breitbart London has gone further: “Anyone who doesn’t realise that The Great Reset is the biggest threat to our form of life right now hasn’t been paying attention (…) this is a takeover by the technocrats. It is a transformation along the lines of fascism and communism, this is terrifying”.

Hundreds of blog posts, videos, and short messages shared on social media have echoed these opinions.

Evangelical Focus asked several people in Europe who have knowledge in the areas of economy about their views on this issue. None of them said they had solid reasons to believe the WEF was part of a conspiration of the elites.

Among them is Amar Breckenridge, a Swiss and Sri Lankan economist with 25 years of experience in international and environmental economics in Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia.

“The WEF is not an international organisation in the sense that intergovernmental organisations like the UN or the WTO are”, says Breckenridge, “and the importance of the organisation has been over-hyped by itself, and, paradoxically, by its critics”.

In the last 20 years, the forum gathering in Davos “has engaged in a large and often bewildering range of issues, ranging from trade and conflict resolution to governance and racism. My own impression based on my areas of expertise is that the WEF has neither the intellectual firepower of a respectable research institution nor the decision-making structure to make a huge impact on these issues”.

Tbe economist believes much of the strong reactions have to do with the name chosen for the initiative. “The expression ‘Great Reset’ is simply a bit of gimmicky vocabulary the WEF seems to have latched upon to repackage these ideas that have a longer history”. The name has achieved to give “an air of mystery, if not mysticism, which might be a contributor to the suspicion it has elicited in some corners”. But “it is worth noting that expressions of the sort ‘great something or other’ (‘acceleration’, ‘recession’, ‘decoupling’, ‘transformation’) are all things we have heard about over the last 20 years”.

Conversations between governments in the late 90s and the global financial crisis of 2007-10 already addressed all the themes now presented by the WEF. “The need for taxes and regulations on things like the emissions of pollutants and greenhouse gases; and public investment in health and education” are policies discussed for a long time in “mainstream economics”. “To go around claiming that these ideas are therefore an example of incipient Bolshevism is to be ignorant in the extreme”, he adds.

Breckenridge argues that it is obvious that for some global challenges like environmental deterioration and climate change there is no other option than cooperation between countries.

“There is a long history of such agreements. The experience of the second world war, and the inter-war economic power rivalry that worsened the great depression and contributed to the second world war, inspired the nations to come together to set up institutions to secure global public goods. The UN is one of these. The IMF is another. The GATT (and then the WTO) is a third”.

The problem, says Breckenridge, who studied Philosophy and Economics at Oxford University, is that “arguments about sovereignty have the advantage of appealing to one of the baser instincts of humanity: nationalism”.

Especially if these globalist fears find a connection with theology. “Unfortunately, evangelicalism has proven to be a fertile ground for such conspiratorial thinking”, says the economist, who is himself a member of an evangelical church. “The current conspiratorial talk in right-nationalist, and Christian fundamentalist, circles says that the WEF is a trojan horse for an insidious Marxist agenda”.

“A particular apocalyptic view of the world” of certain “American evangelicalism” does not help either. “If you see yourself on a divinely ordained mission, you do not adjust your views when faced with the facts. You dismiss the facts as part of a plot against you and make your faith one long exercise in confirmation bias”.

But is there not a real concern about the growing power and lack of accountability of the big tech giants, and their capacity to limit the behaviours of people?

Yes, but the challenges faced today cannot simply reduced to the action of one organisation. “Regardless of how it views itself, the WEF lacks the mandate and legal mechanisms to lead such an ambitious plan. It can facilitate the process by bringing interested parties together. But ultimately, decisions will be made by sovereign states in the fora that matter: in their parliaments, through their courts; and in international organisations”.

Breckenridge concludes its in-depth reflection (read his full answers here) that churches should remind people that “conspiratorial thinking is bad witness. The core claim of evangelicalism is that an event – the death and resurrection of the son of God – is true, even if wholly improbable at first glance. If Christians develop a reputation for saying or believing any old thing, the world can be forgiven for thinking Christians are unreliable witnesses to last week’s weather, let alone to an event that happened 2000 years ago”.

But furthermore, Christians “need to articulate a biblical theology of creation and redemption and engage with global efforts on that basis. We need to remind the world that the gospel is physical and spiritual. And we need to take seriously the Bible’s mandate to speak truth to power, and ensure that in all these efforts the voice of the outcast, the oppressed and the poor are heard”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus – life & tech – Is ‘The Great Reset’ a plan of the global elites to restrict our freedoms?