Some with something to gain make false claims of voter fraud, illegality. That causes many to distrust elections.

By Patrick R. Miller

Many in the politics industry profit from claiming that fraud and illegality plague our elections. Some probably think that they can push that false narrative with no consequences, at least for themselves. If the tactic works and their audience believes it, then why stop?

Undermining the legitimacy of our elections indeed has consequences. Typically, it “just” further alienates an already distrusting public from their government, and disrespects election officials — your neighbors — who serve honorably.

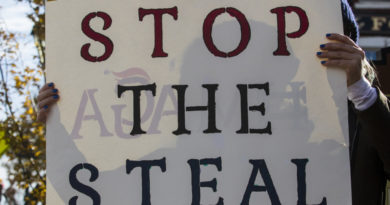

But January 2021 raised the stakes. A lie about a stolen election caused a pro-Trump mob to attack the U.S. Capitol. Some shouted for the vice president to be hanged. Their riot left six dead, including two police officers. (One officer died during the riot, the other later by suicide.)

Elections shouldn’t have death tolls. Many Americans now fear that distrust of our elections is birthing a new era of election-related violence.

Here is reality: American elections are generally free, fair, and legal. We do not have a problem with widespread fraud that alters election outcomes. Our state and local election officials are largely honest and professional public servants.

Yes, our process could be fairer. Partisan gerrymandering, for example, diminishes the value of your vote. And some rules arguably make voting harder for citizens.

Yes, our process is too partisan. Many in politics do not prioritize maximizing citizen access to the ballot as a non-partisan goal.

Yes, our process is also imperfect. Some small error naturally exists — thus, recounts. Some small amount of fraud exists — thus, prosecutors. Election law isn’t always clear — thus, courts.

But imperfect doesn’t equal illegitimate. And we can fairly debate election reform without delegitimizing the process.

Once the rules are set, our elections generally works well. I know many won’t want to believe that.

Most Americans are understandably cynical about politics. That cynicism tempts us to believe that government can only fail or victimize us.

Many in the politics industry — politicians, party officials, activist groups, ideological media — exploit that cynicism to cast doubt on election integrity.

Why? It’s a good schtick. It can advance policy goals. It can be profitable. We see it in Kansas.

Former Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach got famous partly on his voter fraud claims but couldn’t find much of it when he had the actual power to uncover it.

Certain progressive voices in Kansas political social media have validated false allegations that party and election officials fix primary elections against progressives.

The Kansas attorney general recently joined a failed Texas lawsuit that claimed certain states had illegally conducted their elections. That case could have overturned the presidential election. But strategically, it also would have helped conservative efforts nationwide to limit local control over election administration and centralize that power in more conservative state governments.

The conservative Judicial Watch falsely claimed that Johnson County had more registered than eligible voters in 2020. Attacking the integrity of the mostly Republican officials who oversee Kansas elections got them the national attention they sought from politicians and ideological media who also profited from that falsehood.

Different political goals, same core argument that delegitimizes elections.

Trusting government is hard, especially when trust means accepting election losses. But we should give our election officials the trust and credit they deserve. And we must reject the myths of systematic election fraud, rampant conspiracies, and fundamental illegality.

The stability and peace of our democracy depend on it.

Patrick R. Miller is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Kansas. He can be reached at patrick.miller@ku.edu.

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Topeka Capital-Journal can be found here ***