A Republican donor gave $2.5 million for a voter fraud investigation. He wants his money back.

Like many Donald Trump supporters, conservative donor Fred Eshelman awoke the day after the presidential election with the suspicion that something wasn’t right. His candidate’s apparent lead in key battleground states had evaporated overnight.

The next day, the North Carolina financier and his advisers reached out to a small conservative nonprofit group in Texas that was seeking to expose voter fraud. After a 20-minute talk with the group’s president, their first-ever conversation, Eshelman was sold.

“I’m in for 2,” he told the president of True the Vote, according to court documents and interviews with Eshelman and others.

“$200,000?” one of his advisers on the call asked.

“$2 million,” Eshelman responded.

Over the next 12 days, Eshelman came to regret his donation and to doubt conspiracy theories of rampant illegal voting, according to court records and interviews.

Now, he wants his money back.

The story behind the Eshelman donation – detailed in previously unreported court filings and exclusive interviews with those involved – provides new insights into the frenetic days after the election, when baseless claims led donors to give hundreds of millions of dollars to reverse President Joe Biden’s victory.

Trump’s campaign and the Republican Party collected $255 million in two months, saying the money would support legal challenges to an election marred by fraud. Trump’s staunchest allies in Congress also raised money off those false allegations, as did pro-Trump lawyers seeking to overturn the election results – and even some of their witnesses.

True the Vote was one of several conservative “election integrity” groups that sought to press the case in court. Though its lawsuits drew less attention than those brought by the Trump campaign, True the Vote nonetheless sought to raise more than $7 million for its investigation of the 2020 election.

Documents that have surfaced in Eshelman’s litigation, along with interviews, show how True the Vote’s private assurances that it was on the cusp of revealing illegal election schemes repeatedly fizzled as the group’s focus shifted from one allegation to the next. The nonprofit sought to coordinate its efforts with a coalition of Trump’s allies, including Trump attorney Jay Sekulow and Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., the documents show.

Eshelman has alleged in two lawsuits – one in federal court has been withdrawn and the other is ongoing in a Texas state court – that True the Vote did not spend his $2 million gift and a subsequent $500,000 donation as it said it would. Eshelman also alleges that True the Vote directed much of his money to people or businesses connected to the group’s president, Catherine Engelbrecht.

Asked about the shifting focus from allegation to allegation, Engelbrecht said, “A good thorough investigation takes the course it takes, and we were not going to expose whistleblowers to make a quick headline.” She said that the group’s investigation “is ongoing even now.” In court documents, True the Vote says Eshelman’s money was spent properly.

True the Vote’s lawyer, James Bopp, said that no conditions were attached to Eshelman’s donations and he is not entitled to the return of his money just because he didn’t like the outcome.

The court documents and interviews show how quickly Eshelman and his allies became disillusioned with True the Vote.

“We were just not getting any data or proof,” said Tom Crawford, who had worked for Eshelman as a lobbyist and served as his representative on the True the Vote effort. “We were looking at this and saying to ourselves, ‘This just is not adding up.’ “

True the Vote was formed in 2010 by Engelbrecht, a Texas-based tea party activist. Engelbrecht, 51, came to prominence during the Obama administration partly for accusing the Internal Revenue Service of improperly targeting True the Vote and other conservative nonprofit groups.

True the Vote has spent the past decade aggressively promoting claims of voter fraud and pushing for voter-identification laws. The group has established itself as a hub for training volunteer poll watchers to monitor voters for their eligibility. Democrats have accused it of trying to intimidate minorities and other low-participation voters.

As a nonprofit, True The Vote is required to be nonpartisan, and Engelbrecht has said that its mission has nothing to do with party politics. But it has worked with Republicans on other campaigns – for instance, partnering with the Georgia GOP on a “voter integrity” effort for last month’s Senate runoffs in that state.

Eshelman, 72, was not familiar with True the Vote before Election Day. A drug company founder turned financier whose Wilmington, N.C.-based firm invests in health-care companies, he had previously donated largely to initiatives and groups that championed free-market principles and attacked Democratic candidates.

But after Biden jumped ahead – a shift election experts had expected as mail-in ballots were tallied – Eshelman asked Crawford for advice on funding an operation to determine if widespread fraud existed. Crawford agreed to help as an unpaid, informal adviser.

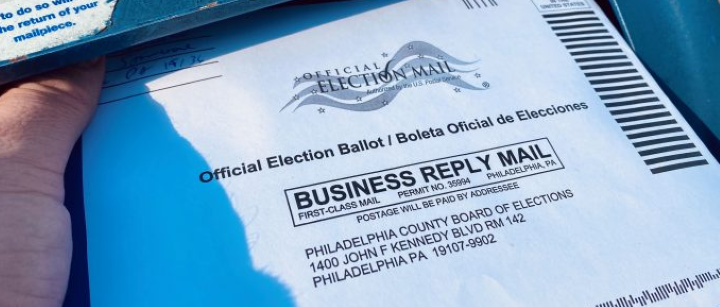

“I thought about the range of possibilities around vote fraud,” Eshelman said in an interview with The Washington Post. “There was already noise around cities like Detroit, Milwaukee, Atlanta and Philadelphia.”

He added: “I wanted to determine if this was legit. Can we find a real smoking gun?”

Eshelman’s Nov. 5 donation was easily the biggest gift True the Vote had ever received, according to a person familiar with its operations, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss matters in litigation. True the Vote had never raised more than $1.8 million in a single year, its tax returns show.

The windfall propelled the nonprofit into action.

That evening, Engelbrecht sent Crawford a one-page summary of the group’s ambitious new “Validate the Vote 2020” campaign. It included a budget of $7.3 million and envisioned plans to set up cash rewards for whistleblowers, analyze voter data to identify “patterns of election subversion” and file lawsuits to “nullify the results” in seven battleground states.

In a news release announcing the whistleblower program the next morning, Engelbrecht said: “Unfortunately, there is significant tangible evidence that numerous illegal ballots have been cast and counted in the 2020 general election, potentially enough to sway the legitimate results of the election in some of the currently contested states.”

But over the following days, in federal lawsuits True the Vote filed in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, the group said the evidence for its claims was still being developed.

The suits, filed by Bopp, said True the Vote would use “sophisticated and groundbreaking programs” to show that enough illegal votes had been cast – by noncitizens, felons, fake voters and others – to swing the election to Biden. “This evidence will be shortly forthcoming,” each complaint said.

Bopp, whose firm received a retainer of $500,000 for its work on the lawsuits, told The Post that there was “tons of evidence” of voter fraud but that it was “anecdotal, circumstantial.”

True the Vote and Eshelman believed that finding people in swing states with vivid tales of voter fraud would be a crucial part of the project’s success, according to emails. Crawford gave Eshelman regular updates about True the Vote’s progress on that front.

“We need [True the Vote] to get whistleblowers vetted and ready and to get their data teams beefed up,” Crawford told Eshelman in a Nov. 10 email.

Later that day, Crawford reported to the financier that a man in Yuma, Ariz., had come to True the Vote with allegations of large-scale “ballot harvesting” by Democrats in the region. “Please God let his story pan out,” Crawford wrote.

“Sensational,” Eshelman replied, adding that he was “still committed to putting in big money” if progress was made.

While it scrutinized the accounts of purported whistleblowers, True the Vote also sought to prove fraud through data analysis. Bopp’s lawsuits promised “expert reports” comparing vote tallies with registration databases and other records. True the Vote, he wrote, had “persons with such expertise and data-analysis software already in place.”

Engelbrecht’s Validate the Vote plan, an exhibit in the lawsuit, budgeted $1.75 million for “data and research” work. It was to be led by a company whose name evoked the shadowy world of intelligence operations: OPSEC Group.

Records show that OPSEC had been formed less than two months earlier in Alabama by Gregg Phillips, a former True the Vote board member whose 2016 tweet was the source of the false claim that Trump would have won the popular vote that year but for millions of fraudulent votes by illegal immigrants.

Phillips, 60, and Engelbrecht are business partners in a health-care company. Eshelman alleges in a legal filing – without providing evidence – that the two are also lovers.

In an interview, Phillips denied any such romantic relationship. Engelbrecht declined to comment on the allegation.

On Nov. 12, Eshelman and Crawford joined a conference call with Engelbrecht and Bopp to hear an update on the data analysis and other aspects of the legal plan. “I was encouraged,” Eshelman wrote in an email to Crawford a couple of hours later, but noted: “You did not really give details on whistleblowers. Where are we on that?”

Crawford replied that three whistleblower complaints, including the Yuma allegation, had survived initial screening.

The following day, Eshelman wired another $500,000 to True the Vote.

On that day, Nov. 13, Engelbrecht received a bill for a $1 million publicity campaign from Old Town Digital Agency, an online advertising firm whose founder, Dikran Yacoubian, has worked in Republican politics on and off since the 1990s. Yacoubian had worked with Eshelman and helped introduce him to True the Vote. Eshelman and Crawford then brought Yacoubian on to help plan a publicity campaign.

Most of the money was to cover the upfront costs of online ads to trumpet True the Vote’s fraud findings, according to Yacoubian. The rest, he said, was to be spent on retainers for Republican consultants who would push the project’s findings through political and media channels.

Yacoubian said he had already begun securing the services of these consultants, including Robert Heckman, a longtime strategist for Graham. Yacoubian hoped Heckman would pass the group’s findings on to the Senate Judiciary Committee, which Graham then chaired.

But Engelbrecht didn’t pay the $1 million bill, saying later in an email to Eshelman’s handpicked firm that it had no contractual agreement with True the Vote and had not provided “any services.”

Her refusal to pay contributed to an emerging rift between Engelbrecht and Crawford, who at the same time was growing frustrated by what he described as the group’s vague and ever-shifting leads.

“There was a guy in Georgia who claimed to be the bagman for Stacey Abrams,” Crawford told The Post. “It was, ‘We’re getting an affidavit,’ and then it was, ‘He ran away and we can’t find him.’ “

The “ballot harvesting” whistleblower in Yuma turned out to have already contacted law enforcement, according to the person familiar with the group’s operations. Two people were later indicted on a charge of submitting votes for other people – but during August’s primary, not the general election.

Yacoubian, too, was frustrated that True the Vote’s whistleblowers were not materializing. “I really didn’t get to do, on the promotion side, anything – because there wasn’t anything to promote,” he said in an interview.

At one point, a publicist working for Engelbrecht instead sent Yacoubian an eight-minute video titled “Who Is Catherine Engelbrecht?” that she wanted posted online.

Engelbrecht continued to make promises about whistleblowers, claiming in a Nov. 14 email to Eshelman: “We are writing up the briefs on these individuals now to give Senator Graham and Cruz.”

Heckman, the veteran Graham consultant, said he listened to a pair of conference-call presentations from Engelbrecht and Phillips but came away so unimpressed that he never even mentioned the effort to Graham. “I was asked to determine whether there was any legitimate evidence there,” he told The Post. “My conclusion was there wasn’t.”

In an email, Engelbrecht said the group shared promising early leads with Heckman while it continued to gather information. She acknowledged that her publicist sought help in posting the video.

She denied that True the Vote gave Yacoubian and Crawford nothing to work with, saying that the group’s own publicists were “working non-stop” at the time to issue news releases on its activities. “The fact is that [neither] Dikran nor Tom seemed interested in actually doing anything,” she wrote.

In any case, Crawford’s exasperation was growing.

“We cannot get ANY information from her or her team,” he wrote in a Nov. 15 email to Eshelman. “It goes on and on like this.”

As True the Vote struggled to produce solid whistleblower accounts, its lawsuits also failed to gain traction. Bopp, who serves as the group’s general counsel, told The Post that he reached out to Trump and his legal team with a proposal: that they join forces.

In phone conversations with Sekulow and Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s personal attorneys, Bopp said he urged the Trump legal team to adopt True the Vote’s legal strategy, which hinged on persuading a federal judge to open up access to voter rolls.

“It was becoming clear to me that the lawsuits we filed were not getting the attention they needed” from judges, Bopp said in an interview. “And the Trump legal effort was a disaster, both their strategy and the tactics.”

Bopp said Sekulow and Giuliani supported the proposal and told him they would recommend it to Trump.

Bopp said that, at Sekulow’s request, he briefed a group of Trump allies in a phone call that included Sekulow, Graham and Fox News host Sean Hannity.

Giuliani did not respond to requests for comment. Representatives for Graham and Hannity declined to comment. Sekulow wrote in a text message: “I do not disclose discussions that I may have had on legal matters on behalf of a client.”

Bopp said that on the morning of Nov. 15 he spoke to Mark Meadows, Trump’s chief of staff, and sent him a written proposal about True the Vote’s legal approach. A spokesman for Meadows declined to comment.

According to Bopp, Meadows said he would speak to Trump and get back to Bopp by 3 p.m. that day. But the call never came.

The following day, Bopp decided to abandon all four of True the Vote’s lawsuits, concluding that without the campaign’s involvement the suits had little chance of advancing before the election was to be certified in December. The lawsuits were just one component of the operation Eshelman was funding, but True the Vote had pitched them as critical to overturning the election results.

Bopp told Eshelman about the decision that day, during a tense phone call.

Eshelman was furious, according to court documents and interviews.

On Nov. 17, he sent Engelbrecht an email demanding the return of his money. True the Vote offered on Nov. 23 to return $1 million to settle the matter. Eshelman filed his first lawsuit two days later, saying the group had failed to provide an accounting of how the remainder of his money had been spent.

He withdrew the federal lawsuit on Feb. 1 and filed the suit in Texas state court.

None of Eshelman’s money has been returned, court documents show.

Bopp told The Post his firm ultimately billed True the Vote roughly $300,000 – more than half its retainer – for its work on the four lawsuits. He said he withdrew them because he “could see they were not going to accomplish anything.”

Overall, the experience left several people who were involved in the effort unconvinced that there ever was evidence of voter fraud to be discovered.

Even Phillips, the former True the Vote board member, said he has doubts about the impact of any irregularities. “I don’t know if there was enough to make a difference in the presidential election,” he said.

Crawford said: “I believe very much that Biden won and that anything we saw in terms of irregularities was not widespread enough to have changed the outcome.”

Eshelman said he still believes there was “some misbehavior” in the election. “But do I believe it might have risen to a degree that would change the electoral outcome?” he said. “I don’t know.”