Deep Dive: PPD founder wants back $2.5m contribution after nonprofit failed to prove election fraud to keep Trump in office

WILMINGTON — A voter fraud group in Texas is disputing the central claims of a lawsuit filed by attorneys for PPD founder Fred Eshelman. Eshelman is seeking full reimbursement of $2.5 million that he wired to True the Vote, LLC days after the 2020 presidential election.

Eshelman said he initially wired $2 million to the conservative-leaning nonprofit on Nov. 5 to fund what he thought would be legitimate efforts to expose election fraud in seven battleground states, including North Carolina.

Eight days later, Eshelman wired an additional $500,000 to the group to help their continued “momentum” to uncover widespread voter fraud and litigate accordingly. In the days that followed, however, the Wilmington investor said he became increasingly cynical of the group’s efforts due to what his attorneys described in the Nov. 25 lawsuit as “vague responses, platitudes, and empty promises of followup that never occurred.”

RELATED: Photos and analysis: Trump visits Wilmington, double-voting, supporters and protestors

“[I]n response to requests for specific data relating to potential whistleblowers and how their allegations fit into an overall narrative, [True the Vote President Catherine Engelbrecht] would simply respond with vague comments like: ‘We are vetting’ or ‘They are solid,’” according to the lawsuit.

Eshelman also contended that Engelbrecht consistently ignored inquiries for reports of the group’s purported work to obtain information from state officials who could testify to sweeping election fraud.

The two parties dispute key facts of the case: Eshelman claims an action plan entitled ‘Validate the Vote 2020’ was used to sell him on the group’s efforts before his first contribution. Yet, True the Vote claims Eshelman’s own political consultants helped shape the action plan — most importantly, its litigation strategy — before and after he wired them his donation.

Eshelman’s main legal argument rests on a Nov. 5 phone call with Engelbrecht. They reached an agreement to provide $2 million “on the condition that the funds would be used to fund the initial stages of the Validate the Vote project.”

True the Vote attorney Brock Akers told Port City Daily there was no mention of the contribution coming with stipulations or conditions. Furthermore, he said, no documentation exists to prove it.

“If it was conditional, there would be some document, but there isn’t. It’s just made up,” Akers said.

Arguing a breach of contract, Eshelman’s attorneys said the parties “entered into an enforceable oral contract,” whereby the donation would be made in exchange for True the Vote’s “commitment to undertake specific efforts referred to by Ms. Engelbrecht,” outlined in Validate the Vote’s action plan.

Eshelman, who now heads a Wilmington-based healthcare investment company called “Eshelman Ventures,” denied Port City Daily’s request for an interview, according to his attorney Brendan McCormick. However, on Friday the PPD founder iterated in an email to Port City Daily his commitment to finding justice and pursuing litigation.

“True the Vote failed, in every way, to make use of my directed donation to investigate and either prove or disprove election fraud, as agreed upon, and failed to respond to my requests for information about how the funds were spent,” Eshelman wrote.

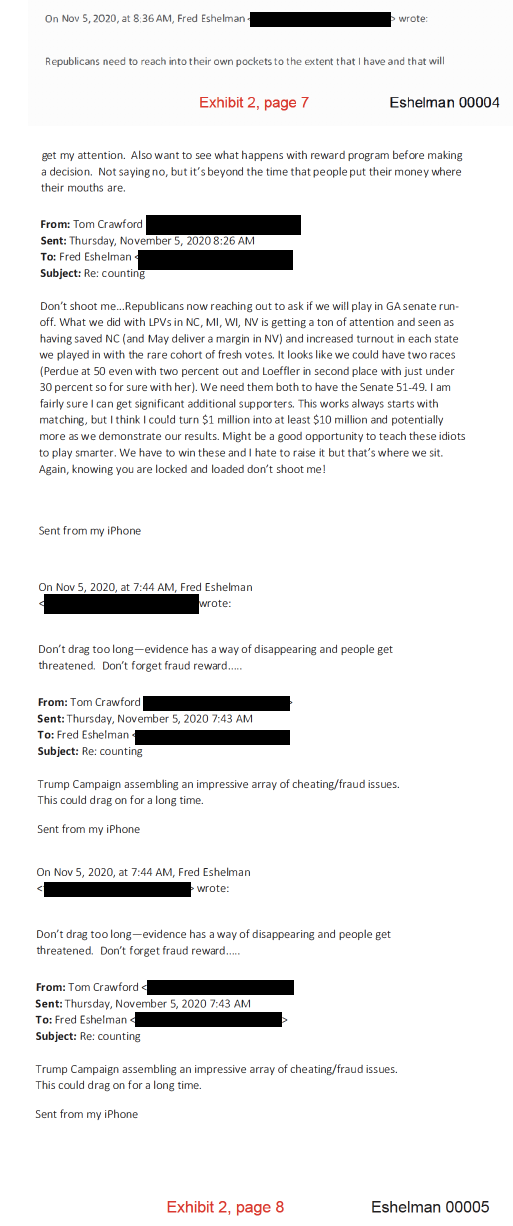

Nothing in the filed court documents suggest Eshelman may have been concerned about disproving election fraud. Emails to a political operative on the morning of the wire revealed his level of enthusiasm to support the president’s push to overturn election results.

“This stuff really needs to be verified, quantified, and a massive information campaign launched at [the] American people. You want a revolt from the Silent Majority, you got it,” he wrote.

On January 6, Trump supporters did revolt and stormed the U.S. Capitol.

Eshelman dropped the federal suit earlier this month to pursue his case in a Texas state court, which McCormick said was done because the claims are “better addressed in the state court.”

Crafting an action plan

The lawsuit claimed Engelbrecht laid out a five-pronged plan called “Validate the Vote” before receiving the initial wire:

- Solicit whistleblower testimonies

- “[B]uild public momentum through broad publicity”

- Galvanize Republican legislative support in key battleground states

- Aggregate and analyze the whistleblower data through a firm called the OPSEC Group

- File federal lawsuits “with capacity to be heard by the Supreme Court of the United States”

The lawsuits would be filed in North Carolina, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Nevada, and Arizona.

Emails and text messages show a timeline of communications between key players throughout Nov. 5. They were included as an exhibit in True the Vote’s response to the complaint and reveal Eshelman’s own political operative, Tom Crawford, was involved in the formulation of the plan itself. Yet, its name, “Validate the Vote,” wasn’t finalized until 2:20 p.m., 10 minutes before a Bank of America associate confirmed the successful $2-million wire.

The exhibit began with emails between Eshelman and Crawford. Crawford previously served as a lobbyist for Eshelman, according to The Washington Post. Both expressed a desire to join Republican attempts nationwide to prove election fraud in battleground states, and Crawford attempted to persuade Eshelman to contribute to the cause.

“Republicans need to reach into their pockets to the extent that I have and that will get my attention,” Eshelman responded to Crawford.

A series of text-message exchanges between Crawford and Engelbrecht began at 10:28 a.m. and show coordination between Eshelman’s representative and True the Vote’s president crafting an action plan.

“Tom, what is the name of the digital firm we’re going through?” Engebrecht asked.

“Old Town Digital Agency. This is the group we use. We have spent heavily building their targeting and data models. They are the best,” Crawford replied before confirming he was Eshelman’s representative.

Roughly 30 minutes later, at 11:12 a.m., Crawford asked Eshelman to call True the Vote’s president. Shortly after noon, Eshelman told Crawford he needed “wiring instructions asap.”

At 1:11 p.m., an Eshelman Ventures employee asked a Bank of America associate to wire the $2 million.

At 1:19 p.m., Eshelman told Crawford he reached out to a friend and “former senior military guy who reached out to some of his contacts with real money.”

“I need something in writing describing what we’re doing, who is involved, end game etc. as well as the ask. He also knows folks offshore who love the US etc but I said that MIGHT BE TRICK [sic], ie inferred interference in [a] US election. What do you think? Anyway, quicker you can send me stuff, the quicker I can get money. Time flying.”

At 2:20 p.m., Crawford texted Engelbrecht: “Validate the Vote. Let me know what you think.”

“I love it,” Engelbrecht responded.

Crawford added, “We have grabbed validatethevote2020.com . . . Ready to roll.”

True the Vote’s response explained its interpretation of the interaction: “[T]he name ‘Validate the Vote’ was given to Catherine Engelbrecht by the political consultant for Mr. Eshelman [Crawford], who also said that he had the rights to the website with that name. That all developed after the contribution was made.”

A Bank of America employee confirmed a successful wire at 2:31 p.m. At 4:58 Engelbrecht emailed the finished action plan document to a man named “Dikran Yacoubian.” According to the Post, Eshelman and Crawford recruited Yacoubian to help design a publicity campaign.

“This will provide the vehicle to serve subpoenas on state election officials to produce critical election data,” according to the plan.

(Ironically, former President Donald Trump faces a possible subpoena in connection to a criminal investigation opened by Georgia prosecutors earlier this month. They’re looking into Trump’s attempts to overturn the state’s election results — a state True the Vote targeted for legislation.)

Akers, one of True the Vote’s attorneys, told Port City Daily the group’s litigation strategy occurred after Eshelman made the contribution, contradicting the lawsuit’s claim that, before the wire, “Engelbrecht represented that Jim Bopp — an attorney affiliated with [True the Vote] —would file lawsuits in the seven closest battleground states with an eye toward serving subpoenas on state election officials to produce relevant election data.”

Bopp is a conservative attorney who represented George W. Bush in his successful Supreme Court case against then-Democratic presidential nominee Al Gore amid a dispute over Florida votes in 2000.

“During their first conversation, nothing was said about lawsuits,” Akers said of Engelbrecht’s initial phone call with Eshelman. “He asked for the [action plan] sheet. He said he’d try to get more money but he wanted something in writing. That’s when Catherine [Engelbrecht] came up with the one-pager.”

This contradicts Eshelman’s claim that the detailed plan outlining the group’s litigation strategy and budget requirements was pitched to him as a means to obtain his contribution. True the Vote claimed the same plan was drawn up after “Eshelman expressed a desire to get more contributors for the project, which we all knew would be an expensive undertaking.” It was finalized only after the contribution was wired.

This argument is aided by the fact Engelbrecht sent the finished plan to Yacoubian more than two hours after the wire transfer was confirmed.

“[Eshelman] asked for a document to outline the plan for him to use with others. After the contribution, and then after both the legal strategy outlined by [Engelbrecht’s] attorney Bopp and the naming of the new project as ‘Validate the Vote,’ a new strategy was proposed,” according to True the Vote’s filed response.

It was only then that Engelbrecht “put together a project sheet for ‘Validate the Vote,’ which included its five goals,” according to True the Vote’s response.

The plan concluded that if election fraud was proven, “making the results of the election doubtful,” the various lawsuits would seek to keep Trump in office by nullifying the states’ election results and pick Trump-voting electors through a special election or through the state legislatures.

‘Things went south’

True the Vote sought $7.3 million for their efforts — an amount far exceeding their typical budget. Though, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the $225 million raised by the Republican Party in two months.

“Based upon information and belief, that amount was well in excess of Defendant’s 2019 budget, which [Eshelman] understands was approximately $750,000,” according to the lawsuit.

Although Eshelman said he was provided with complaints filed in four battleground states, “he was not provided any specific update on the status or strategy behind those cases.” Nor was he given litigation status in the remaining three states.

As deadlines for state election results approached, Eshelman said he asked for a teleconference with Engelbrecht and her associates, which took place on Nov. 16. The complaint states that during the call, Engelbrecht and Bopp continuously failed to respond to specifics regarding updated proposal plans, all of which Eshelman agreed to fund.

Furthermore, Eshelman’s attorneys said various district court records revealed True the Vote had dismissed complaints filed in four of the targeted states, a move that Eshelman understood “upon information and belief ” was made in concert with attorneys for the Trump campaign.

A day after the teleconference, Eshelman formally requested a refund of the “balance of his $2.5 million contribution.”

“Also send a full accounting of all monies spent out of the $2.5M, which should be de minimis [too trivial to merit consideration] since nothing was accomplished over the 10 or so days,” he wrote in an email to Engelbrecht.

Relations between the two parties further deteriorated on Nov. 13, when Engelbrecht received a bill from Eshelman’s consultants for $1 million.

“When she questioned the invoice, everything went south,” Akers said and added it was due to certain ethical responsibilities required of a nonprofit corporation.

According to the lawsuit, Engelbrecht did not respond to Eshelman’s full refund request, nor did she respond to a Nov. 19 email asking for an acknowledgement of his wiring instructions “to return the bulk of the money I put in.”

Eshelman then sent a letter on Nov. 21 that requested True the Vote confirm its intention to return the $2.5 million in full by the morning of Nov. 23.

The complaint claims Engelbrecht finally responded via email on the evening before the deadline, but instead of agreeing to a reimbursement, she “continued to engage in dilatory tactics, claiming without any specificity that her group did not ‘expect to have complete information on what [it had] spent on the project this month until the next month.’” Additionally, she told him commitments to whistleblowers must be fulfilled, and she was “committed to activities that we must complete.”

She assured Eshelman’s attorney that True the Vote had spent the $2.5 million on the Validate the Vote project, according to the original complaint.

Later that evening, the attorney conveyed to Eshelman that his client decreased his reimbursement request to $2 million, noting the “limited reports” he received had convinced him that True the Vote did not spend more than $500,000 of his contributed funds.

Again, Engelbrecht did not respond and failed to wire $2 million by the new deadline of 10 a.m. the next day, the lawsuit claimed.

Eshelman’s attorney sent a final demand letter that clarified a failure to wire $2 million before 5 p.m. would force Eshelman “to seek judicial intervention to obtain the requested funds.”

At 5:30 p.m., Bopp sent a letter stating that True the Vote offered a $1-million reimbursement in exchange for an agreement to not file a claim. Although the lawsuit does not clarify whether Eshelman responded to the offer, it notes no wire transfer was made by Nov. 25, the same day Eshelman’s attorneys filed a federal lawsuit.

The lawsuit rested on what Eshelman’s attorney described as a mutual understanding between the two parties: if True the Vote deviated from its proposed plan, “Eshelman would have the right to revoke his conditional gift.”

True the Vote disputes this claim.

Ultimately, Eshelman asked the court to grant a full refund of his $2.5-million contribution, plus interest, attorney’s fees and litigation costs.

True the Vote’s response, filed weeks later on Jan. 21, rested on the premise that Eshelman’s donation was not conditional on any subsequent actions or positive results, “no matter how many times Plaintiff chooses to characterize it in that manner.” It also stated no conditions were documented in any way and True the Vote’s activities were “completely consistent with the stated objectives of the organization at the time of the donation.” It did point to the ultimate failure of those objectives.

“It is true that the results of the presidential election were not changed by these activities, but neither was there an imposed condition on positive results,” the response stated.

As a “non-partisan public service group,” True the Vote qualified as a charitable institution and, therefore, any contribution is an “irrevocable gift whereby the donor is releasing control of the property to the charity,” according to the group’s response. Additionally, it stated Eshelman “will never be able to prove that True the Vote and Catherine Engelbrecht failed to move forward on the initiatives the parties had discussed.”

True the Vote reasoned its post-election behavior accordingly: “Once the Presidential election occurred, there were revealed a series of irregularities in various states, as widely reported in the media, and equally scoffed at as unreliable in the media. Though there are some skeptical of that which may be fairly called ‘voter fraud,’ since the Wednesday after Election Day there were sufficient identified events to warrant investigation in the days and weeks following the election.”

A breakdown by USA Today in early January showed Trump and his allies filed 62 lawsuits in state and federal courts in their nationwide attempt to overturn election results; 61 of those lawsuits failed due to a “lack of standing” or unsubstantial voter fraud allegations. In a case that didn’t involve an allegation of election fraud, but rather the amount of time voters could fix errors on mail-in ballots, a Pennsylvania judge ruled in favor of Trump. But the number of votes involved in the suit was too small to affect the state’s outcome.

On Monday, the Supreme Court rejected election challenges in Georgia, Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

“We were just not getting any data or proof,” Crawford told the Post earlier this month. “We were looking at this and saying to ourselves, ‘This just is not adding up.’”

Tips or comments? Email mark@localdailymedia.com