COVID-19 and Terrorism in the West: Has Radicalization Really Gone Viral?

According to a recent report published by the United Nations, violent right-wing extremists and jihadists “have successfully exploited vulnerabilities in the social media ecosystem to manipulate people and disseminate conspiracy theories” designed to reinforce their narratives and incite terrorism. From the outset of the coronavirus outbreak it was evident that violent extremists were seeking to take advantage of the growing calamity by working the virus into their existing narratives and increasing the volume of online propaganda. Concurrently, terrorism experts and government officials have warned that “captive audiences,” stuck at home during lockdown, bored and lonely, with little to do but surf the internet, are particularly vulnerable to such efforts. As the assistant commissioner of Britain’s Metropolitan police, Neil Basu, told members of parliament: his “greatest single fear” was that this confluence of factors would result in a rising tide of COVID-driven violent extremism and terrorism. Indeed, practitioners and terrorism scholars alike seem to agree, “COVID-19 and extremism are the perfect storm.”

At the heart of this supposed rise in extremism—at least in the West—is the internet. Because the pandemic has forced people to work and learn from home, they have been spending more time online than ever before. With that allegedly comes a heightened risk of being exposed to extremist content, becoming radicalized, and, ultimately, engaging in violence. And yet, a year since the outbreak began, the data show that the predicted surge in terrorism has not materialized. Of course, one could argue that people are becoming radicalized but have simply yet to act. While there is a lag time between radicalization and mobilization to violence, it is not uncommon for people to make this journey within a few months. More importantly, we contend that the forecasted wave of pandemic-induced terrorism has been exaggerated and rests upon a collection of precarious assumptions. These various assumptions support what we refer to as the “perfect storm” theory of COVID-19 and terrorism, to which we now turn a critical eye. By taking a contrarian view, we hope to encourage a more balanced and rigorous discussion of the pandemic’s effects on terrorism.

Assumption 1: Lockdowns have increased vulnerability to radicalization.

In his address to British parliament, Basu raised concern that under lockdowns “social media [has] such an influence on every single one of us… with no other form of distraction or protective factor around you.” Indeed, lockdowns are thought to have granted terrorists a vast “captive audience” rendered susceptible to radicalization by the pervasive sense of uncertainty and social isolation caused by the pandemic. Additionally, because protective social networks have been disrupted, youth are thought to be largely “unsupervised” and therefore at greater risk of radicalization.

While people are indeed confined to their homes during lockdowns, they are free to go wherever they like online. With the online world as their oyster, there is little impetus for the vast majority, who do not already sympathize with violent extremists, to virtually meander into such forums. Fortunately, even if they did find themselves there, extremist content is unlikely to change their pre-existing non-extremist attitudes. Hence, contrary to what has been suggested, more time online does not automatically increase one’s risk of radicalization.

Virtual risks aside, the uncertainty brought on by the pandemic, as well as the social isolation caused by the ensuing lockdowns, have also been singled out for increasing radicalization. While these hardships are real, we caution against readily inferring knock-on effects. The list of potential risk factors for radicalization is long, and in addition to uncertainty and social isolation, it includes unemployment, mental illness, “trouble in romantic relationships” and “failing to achieve one’s aspirations,” among many other social, psychological, and geopolitical circumstances. Regardless if they have increased during lockdowns, none of these factors are either necessary or sufficient for someone to engage in terrorism, and they lose their intuitive appeal once we consider how many people have similar experiences and yet do not turn to extremism, violent or otherwise. Uncertainty, for example, is so widespread that it is practically ubiquitous, even in the absence of a pandemic, and—quite unlike the risk relationship between cigarettes and cancer—its connection with involvement in terrorism is largely theoretical.

Truth be told, the various factors that trigger radicalization and subsequently—but by no means assuredly—mobilization to violence remain poorly understood. Indeed, piecing together the reasons why one person radicalized to violence is difficult after the fact; making predictions about the prevalence of radicalization based on systemic-level changes is near impossible. To speak of a “perfect storm” suggests a thorough understanding not only of the factors that trigger radicalization, but also of how these factors interact to significantly increase its likelihood. Unfortunately, we have not yet reached that level of understanding. Therefore, just how much more vulnerable our societies have become is presently unclear and we should be careful not to overstate the case. As Basu himself pointed out, “this is anecdotal, so it’s not academic.”

Assumption 2: The number of people engaging with violent extremist and terrorist content online has dramatically increased.

Another assumption often stated as fact concerns significant increases in the number of people engaging with violent extremist and terrorist content online. Indeed, statistics appear to support this at face value. For example, Moonshot CVE discovered significant increases in searches for far-right extremist content in both Canada and the United States following implementation of lockdowns. Large increases in use of right-wing terminology, such as “corona-chan” and “boogaloo” (often paired with calls for violence) have been recorded across various forms of social media. More worrying still, the number of online extremist groups and their followers seem to have proliferated since the pandemic began. For example, the number of boogaloo-focused Facebook groups had reportedly doubled by April, attracting more than 72,000 members, more than half of whom joined within a 30-day period beginning in February. Similarly, membership in the racist “Corona-Chan News” Telegram channel mushroomed, along with significant increases in interactions on popular boogaloo Facebook groups, which explicitly called for violence. Increased traffic to some ISIS-related websites has also been observed.

While these figures are certainly alarming, they might also be deceiving. Searches for extremist content on Google do not, by themselves, constitute evidence of radicalization. Additionally, Google routinely redirects such traffic towards counter-extremist materials, meaning that, regardless of where they ended up, many people have been exposed to counter narratives intended to avert their radicalization. Furthermore, most of this research cannot differentiate activities from users, or track users who have multiple accounts across different platforms. As noted by Moonshot CVE, “It’s entirely possible that in some cases, this is either a very small number of people doing a lot of really intense searching or otherwise it could be a large number of people doing a little bit of searching.” Similarly, the Tech Transparency Project acknowledged that it was unclear how many people belong to more than one group. Given that many online extremist groups are interlinked and promote one another, having multiple group memberships appears to be common practice. Moreover, because many of these online forums are new, subscriber growth may indicate fresh blood or may simply be long-serving extremists creating new forums (such as the now defunct Corona-Chan News) to facilitate discussions related to the pandemic.

There is evidence that at least some of the pandemic-related uptick can be attributed to existing members becoming more active. In a study examining extremist websites (currently under review by an academic journal), researchers at Simon Fraser University found a substantial increase in online activity on right-wing and incel forums, but not others. Interestingly, no forum experienced a significant increase in membership.

While more research is needed, the currently available data do not clearly demonstrate a dramatic increase in the number of people engaging with violent extremist and terrorist content online, nor do they tell us anything about the duration or depth of these engagements.

Assumption 3: Many more people will radicalize to violence.

While simply encountering extremist content online does not inevitably lead to radicalization, several commentators have insinuated that very outcome when discussing the effects of the pandemic. For example, Jonathan Hall, the British Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, asserted that the causal link between spending more time indoors, radicalizing online, and lone actor terrorism is “strong and demonstrable.” But is that really the case?

While “purely web-driven, individual radicalization” can occur, it is relatively rare. An extensive study of “lone actor” terrorists in Europe and the United States found that “social ties are essential to the development of the motivation and capability to commit acts of terrorism” and that lone actors “typically radicalize in both online and offline ‘radical milieus.’” Indeed, the general consensus appears to be that the internet alone does not cause radicalization, rather it is a combination of both on- and offline factors. To the extent that the latter have been impaired by lockdowns and restrictions on social gatherings, half of the equation is essentially missing. It is therefore quite possible that the pandemic may have actually reduced the risks of radicalization to violence.

What exactly extremist groups are doing online must also be examined. To be sure, there has been an increase in extremist activity online, especially amongst right-wing and anti-government groups on social media, and some of this does involve explicit calls for violence. But many of these groups are little more than subversive discussion forums, with inconsistent messaging and vague objectives. It is also unclear to what extent they pose a risk for radicalization and involvement in terrorism. Interestingly, one study of Identitarian and National Socialist groups on Telegram found that

the early stages of the COVID crisis had seen a shift… not towards practices of encouraging violent contention but rather using propaganda to emphasize their contribution in supporting the family unit, communities and the nation, against the failures of authorities in dealing with the virus.

For those who do openly promote violence, mainstream social media companies have been relatively swift to shut them down, and there are now more efforts than ever before to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online. As Hall himself admitted, almost a year into the pandemic, it “remains to be seen” whether the predicted rise in radicalization will actually occur; and this despite findings that people can radicalize to violence within a matter of months.

Assumption 4: The pandemic will lead to more terrorism.

If the pandemic is truly a perfect storm leading people to radicalize, there will be more terrorism. When exactly that might materialize is unclear, but the data we have found suggest that, so far, it has not been the case. This is somewhat unsurprising given that historical records do not reveal any established relationship between pandemics and terrorism.

According to the second author’s personal database of jihadist terrorist attacks in the West, 2020 logged 21 incidents, a marked increase from just seven in 2019. However, jihadists were exceptionally idle in 2019. With a yearly average of 18 jihadist attacks in the West since 2014, the tally for 2020 represents somewhat of a rebound to “normal” levels, albeit slightly above average. Moreover, we have found only four attacks and two plots that involved any mention of COVID-19 (see Table 1). Of these, only two cases were ostensibly triggered by the pandemic: a stabbing in Romans-sur-Isère, France in April and a disrupted plot in Barcelona the following month. In sum, as noted elsewhere, the impact of the pandemic on jihadist terrorism in the West has so far been negligible.

Table 1. Jihadist terrorism incidents in the West linked to the pandemic during 2020.

| Date | Location | Incident | Suspect | Link to Pandemic | Argument Refuting Link to Pandemic | Notes | Our Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April | France | Stabbing | Abdallah Ahmed-Osman | Suspect told police he could no longer bear staying in his small apartment during lockdown. | Suspect dismissed the jihadist literature found in his home, indicating a possible attempt to misdirect authorities. | A psychiatric assessment will determine suspect’s mental fitness at time of attack. | Lockdown possibly contributed the individual’s radicalization and mobilization to violence. |

| April | France | Vehicular Attack | Youssef T | Targets of attack were two policemen patrolling during lockdown. | Choice of targets may have been opportunistic. In a letter explaining his attack, he reportedly wanted to die a martyr but it is unclear if the pandemic was mentioned. | Suspect had prior involvement with the criminal justice system in 2010 for acts of violence. | Motives and ensuing attack seemingly unrelated to pandemic. |

| May | Spain | Alleged attack plot | Unnamed man, aged 34 | Investigators noticed a “striking and worrying” change in his behavior after a state of emergency was declared and he lost his job. | Suspect had already been identified as a terrorism suspect four years previously. | Suspect was being guided by an ISIS handler. A plan to attack a soccer match was abandoned after it was cancelled due to COVID. | Losing his job due to coronavirus restrictions likely triggered the already radicalized suspect to act. |

| June | United Kingdom | Alleged plot to use explosives | 14-year-old minor | Suspect radicalized quickly, proceeding to experiment with explosives during lockdowns. | Suspect had engaged with ISIS propaganda since at least February, before lockdowns. | Suspect was acquitted. | Lockdown may have accelerated plot, but irrelevant to radicalization. |

| Oct | France | Stabbing | Brahim Aouissaoui | Suspect tested positive for COVID-19 after attack. | Unclear if having COVID-19 factored into his decision-making or that he even knew prior to the attack. | Pandemic seemingly irrelevant to radicalization and motive. | |

| Nov | Austria | Shooting spree | Fejzulai Kujtim | Attack conducted hours before Austria’s second lockdown set to begin. | Suspect was on parole: previously convicted for trying to join ISIS in 2019. | Lockdown may have influenced timing of attack, but irrelevant to motive. |

Table 2. Right-wing terrorism incidents in the West linked to the pandemic during 2020.

| Date | Location | Incident | Suspect | Link to Pandemic | Argument Refuting Link to Pandemic | Notes | Our Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March | United States – Missouri | Alleged plot to attack hospital | Timothy Wilson | COVID-19 seemingly accelerated what he referred to as his “Operation Boogaloo”, targeting a hospital caring for COVID-19 patients. | Domestic terrorism investigation started in 2019. Moreover, Wilson bought bomb-making materials in January, before lockdowns were in place. | Wilson had considered other targets, including a school with a large population of black students, a synagogue and a mosque. | The pandemic influenced the timing and choice of target but was not the impetus for radicalization or plotting. |

| March | United States – California | Train wreck | Eduardo Moreno | Moreno crashed a train to bring attention to nearby hospital ship, there to support the COVID-19 response but he believed was for some other nefarious purpose. | [None found] | While the train crash appears motivated by a conspiracy theory, there is seemingly no link to an extremist ideology. | While the pandemic seems to have motivated the suspect to act, it is unclear if this incident qualifies as terrorism. |

| May | United States – Nevada | Alleged plot to attack protesters | Stephen Parshall, Andrew Lynam, and William Loomis | Opposition to lockdowns was catalyst for these “Boogaloo boys” accused of plotting to incite mass violence at BLM protest. | Loomis, told police that he was looking for an outlet to express his rage, anger and frustration at the United States. | The pandemic acted as an initial catalyst for the conspiracy. However, it is unclear if it played a role in their radicalization. | |

| May – June | United States – California | Shooting | Stephen Carillo and Robert Justus | Friend claims quarantine played a role in pushing Boogaloo-inspired Stephen Carillo towards violence. | Unclear motives. Carillo may have been primarily motivated by anti-government sentiment. | Friend’s assessment is the only source currently indicating that the pandemic played a role. | Available information suggests pandemic contributed to Carillo’s radicalization. |

| June | United States – Missouri | Suspected plot to attack protesters and/or police | Cameron Swaboda | Suspect claimed he might have to “go to war” with military or police in response to lockdown. | FBI believe Swaboda was preparing for an attack on Black Lives Matter protestors. | Suspect charged with weapons offences only. | The pandemic possibly contributed to radicalization. |

| Aug | United States – California | Issuing threats | Alan Viarengo | Suspect, (affiliated with the Boogaloo movement), arrested for sending dozens of threatening letters to public health official. | Viarengo has a long history of sending threatening letters to public officials, dating back to the 1990s. | Unclear if Viarengo’s behavior would meet the criteria of terrorism. | Pandemic a catalyst for action but radicalization and threatening behaviors long pre-date COVID-19. |

| Oct | United States – Michigan | Alleged kidnapping plot | Adam Fox et al. | Conspiracy to kidnap the governor of Michigan in response to her lockdown measures. | At least two plot leaders, Adam Fox and Barry Croft, appear to have been radicalized long before the pandemic. | Fox wanted to try the governor for ‘treason’ and said they would execute the plan before the November 2020 elections. | Lockdown seems to have been a catalyst for action, although leaders were already anti-government extremists. |

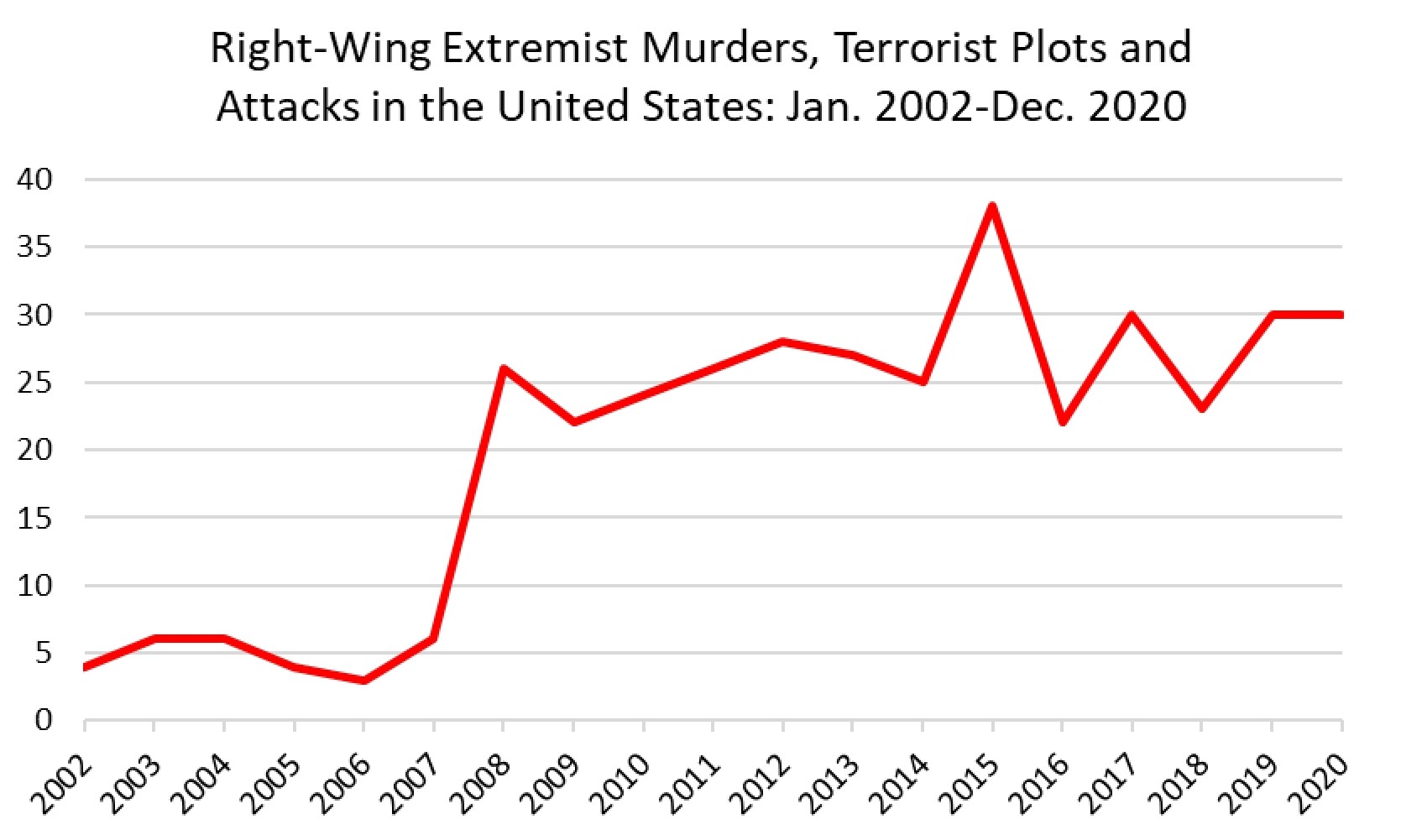

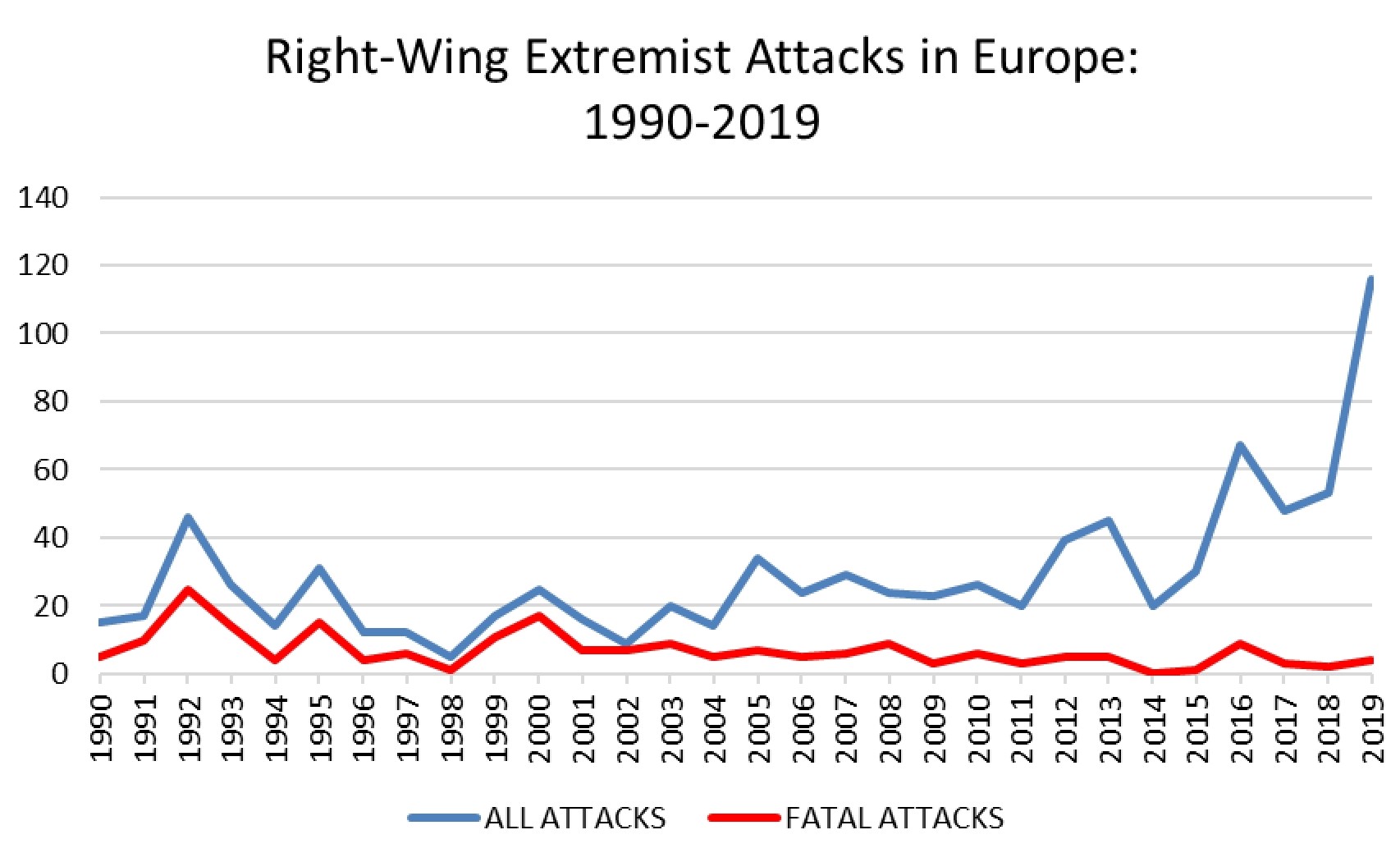

The story of right-wing terrorism is slightly more complex, and the data more fragmented. For the United States, the Anti-Defamation League has recorded a steady rise in white supremacist propaganda since 2017, with a sharp increase in 2020. Yet, except for 2015, right-wing extremist murders, terrorist plots, and attacks have remained relatively stable for the last decade (see Figure 1). Unfortunately, we could not find up-to-date, longitudinal data for Europe. The most comparable dataset, curated by the Center for Research on Extremism, shows non-fatal, right-wing violent attacks have been on the rise from 2014 to 2019 in Western Europe (see Figure 2). Thus, any uptick in attacks for 2020 could simply be the continuation of a historical upward trend, and difficult to disentangle from the potential effects of the pandemic.

Altogether, these various data sources suggest the pandemic has not, until now, generated a surge in right-wing terrorism. That is not to say that it has had no effect at all. We have found seven right-wing motivated incidents which qualify as terrorism and where the pandemic has ostensibly played some role—all of which took place in the United States (see Table 2). Of these, the clearest example of a COVID-driven plot was the conspiracy to kidnap the governor of Michigan in retaliation for “unconstitutional” lockdown measures she had introduced. Yet even here, the available information suggests that at least two of the plot leaders were radicalized long before the pandemic. Additionally, several of these cases appear to have been influenced just as much, if not more, by the Black Lives Matter protests which erupted in response to the killing of George Floyd.

Conclusion

Trends in terrorism are notoriously difficult to predict. Depicting the pandemic as a perfect storm is reminiscent of previous attempts to forecast how exceptional events will impact terrorism, such as when the Arab Spring was heralded as the demise of al Qaeda, or when the collapse of the ISIS “caliphate” was expected to cause a wave of terrorism by returning foreign fighters. These predictions were logically sound, but people do not always act logically.

The “perfect storm” theory of the pandemic’s impact on terrorism is also logical, yet its assumptions have not been carefully considered. Lockdown conditions have unquestionably been challenging, but it is not yet clear whether and to what extent our collective vulnerability to violent extremism has increased. People are spending more time on the internet, but this does not necessarily increase their chances of engaging with extremist content, even if they are bored and lonely. Among those who have encountered such content online, the risk of radicalization is generally low and as our data show, there has so far been no spike in terrorism.

We would be remiss not to point out the various other manifestations of violence such as the possession of weapons and home-made explosives, online threats, physical assaults, violent protests, and destruction of public property, all of which were clearly linked to circumstances arising from the pandemic. Sadly, anti-Asian hate crimes have also proliferated during the past year. However, these incidents do not meet the threshold of terrorism. Indeed, the vast majority of people driven to hatred and violence during the pandemic, including members of the Boogaloo and QAnon movements, have engaged in various forms of criminality that occasionally get dangerously close to, but ultimately fall short of, qualifying as acts of terrorism. Where precisely the storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 sits within this context is presently unclear, but it does not change the fact that the vast majority of people driven to violence amidst the pandemic have done so through relatively low-level forms of crime.

Some will maintain that it is too early to pass judgement, that the incendiary effect of the pandemic has been tempered by the associated restrictions of movement and that the “perfect storm” is still brewing. While we cannot rule out that possibility, it is insufficient to simply argue about when if the underlying why is flawed. As we have seen, the premise that the pandemic will result in more terrorism is based upon a series of assumptions that—although not entirely disproven—are far from foregone conclusions. In writing this article, our goal is to offer a contrarian view to the conventional wisdom about the impact of the pandemic on terrorism in the West. Above all, we wish to stimulate a more thoughtful debate and thorough analysis.

Image: Members of the Proud Boys join supporters of US President Donald Trump as they demonstrate in Washington, DC, on December 12, 2020. Photo by Jose Luis Magana/AFP via Getty Images

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Just Security can be found here ***