Year of COVID-19: Explore the Past and Future of Wisconsin

MILWAUKEE — A year ago, for many Americans, COVID-19 got real.

What started as a faraway threat quickly started hitting close to home. As March rolled around, we saw a rapid succession of scary events: Cases grew stateside, the World Health Organization called the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic, and the U.S. declared its own national emergency.

We’re using this anniversary to look back on the past year of the pandemic, thinking about where we’ve been and what lessons we can take away.

In this article, we’ll unpack some of the trends that have affected Wisconsinites across different parts of life: The spread of the virus, the state’s response, the recent arrival of vaccines, education, social impacts, and economic impacts. We’ll also look toward the future to see where our state is heading.

The story of our year is one of historic moments, devastating losses and incredible resilience. So let’s dive in.

How COVID-19 spread

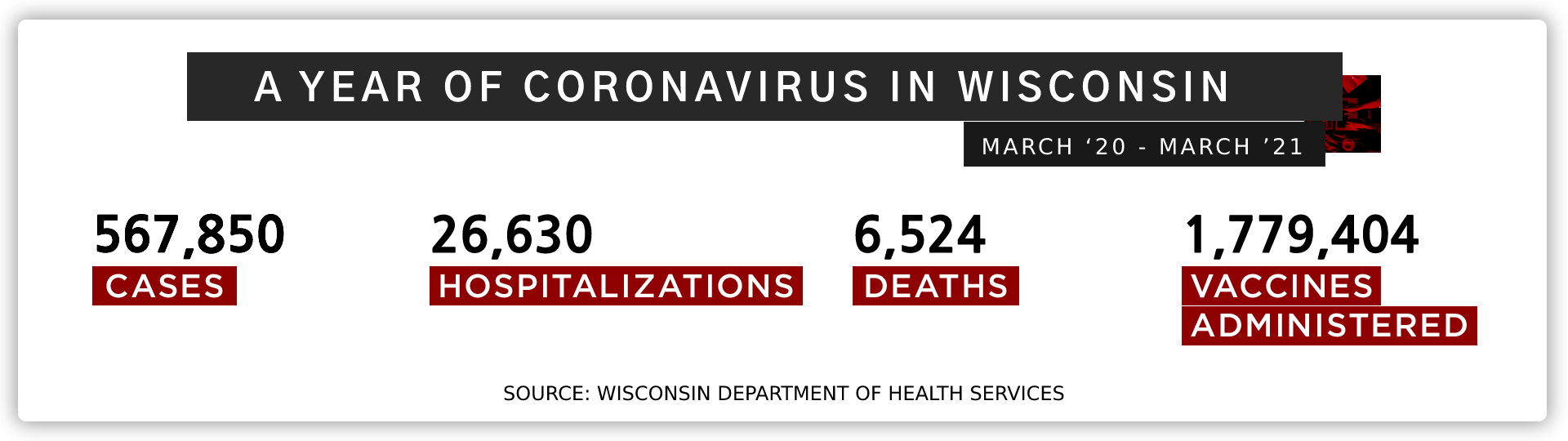

On Feb. 5, 2020, Wisconsin reported its very first case of the novel coronavirus — back before the disease had even gotten the name “COVID-19.” At the time, the Department of Health Services stressed that the risk for the general public was still low. But that risk just kept on rising. Since the initial infection, more than 560,000 Wisconsinites have gotten sick with the virus and more than 6,500 have died.

At first, older Wisconsinites bore the brunt of the pandemic: In mid-April, the 65-and-up age group had seen the highest number of cases, according to DHS data. But younger people soon started getting sick, especially after the state reopened in the spring. To date, residents aged 25 to 34 make up the biggest share of infections.

Through the spring and summer, infection rates fluctuated, ramping up a bit in mid-July before ticking down again. As fall approached, though, COVID-19 started skyrocketing to new heights, led at first by growing numbers in Northeast Wisconsin and the Fox Valley.

September through November saw a huge and sustained surge that turned Wisconsin into one of the nation’s hotspots. Public health officials warned that Wisconsin was “in crisis” as case rates climbed exponentially across the state. By October, the state had opened its Alternate Care Facility — a field hospital to host overflow patients from strained health care systems.

Luckily, trends in Wisconsin have since dropped off from those alarming heights. Infections have been ticking down since the start of the year, and have recently reached their lowest levels in months. So, even as DHS officials still say we aren’t out of the woods yet, it looks like we’re at least on the right track.

Badger State response

If you’ve gotten some degree of whiplash from following Wisconsin’s pandemic response, you’re probably not alone. Since the beginning, the state has seen constant battles over public health measures in the courts and in the legislature.

Gov. Ton Evers first declared a public health emergency in the state on March 12. Weeks later, the measure was followed up with a “Safer At Home” order that closed businesses across the state, banned gatherings between households, and prohibited non-essential travel.

The real trouble began after Evers extended the order through the end of May. Leaders in the Wisconsin legislature filed suit in the state Supreme Court, saying Evers had overstepped his reach. And, on May 13, the court agreed — overturning the stay-at-home measure and leading to a rapid reopening across the state.

Evers and the DHS later declared a statewide mask mandate in July, and in October added a measure limiting indoor gatherings. Both measures faced backlash and lawsuits from different groups, including private citizens, a conservative law firm, and the Tavern League of Wisconsin.

The indoor capacity limit was eventually put to a halt by these legal efforts. In February, the legislature voted to repeal the mask mandate as well — but an hour later, Evers issued a new one.

Vaccines

On Dec. 14, Wisconsin saw a glimmer of hope for the end of the pandemic: The first doses of the newly approved Pfizer vaccine arrived, and health care workers across the state stepped up to get their shots. “We need to save more lives, and I think this is the way to do it,” said Tina Schubert, the first UW Health employee to get her vaccine.

We now have three different approved vaccines — from Pfizer, Moderna, and most recently, Johnson & Johnson — which are all safe and highly effective at preventing COVID-19’s worst effects. More than 1 million Wisconsinites have gotten at least one shot, and more than 600,000 have completed the vaccine series for full protection.

Rolling out the vaccines hasn’t always been a smooth road. Early on, Wisconsin faced criticism for its relatively slow pace of getting shots in arms and confusing guidance on how to book an appointment. And in a case that got national attention, a Grafton pharmacist intentionally ruined hundreds of vaccine doses based on a conspiracy theory that they were unsafe.

Recently, though, Wisconsin’s vaccination rate has gotten a boost. Wisconsin is now one of the leading states in getting its allocated shots into arms, and vaccine supply has grown as production ramps up — though state officials say it’s still not enough to meet the full demand. More than 60% of Wisconsinites aged 65 and up have gotten at least one dose, according to DHS data.

As March has kicked off, more groups have become eligible for the shots, starting with teachers as the top priority. The state launched its online registry to connect residents with vaccine providers across Wisconsin. And, with Johnson & Johnson’s one-dose vaccines added to the mix, it’s expected that anyone who wants a shot should be able to get it in the next few months.

Education

In March 2020, as the state was entering its strict Safer At Home lockdown, Evers ordered the DHS to shut down K-12 schools. “Keeping our kids, our educators, our families, and our communities safe is a top priority,” Evers said at the time.

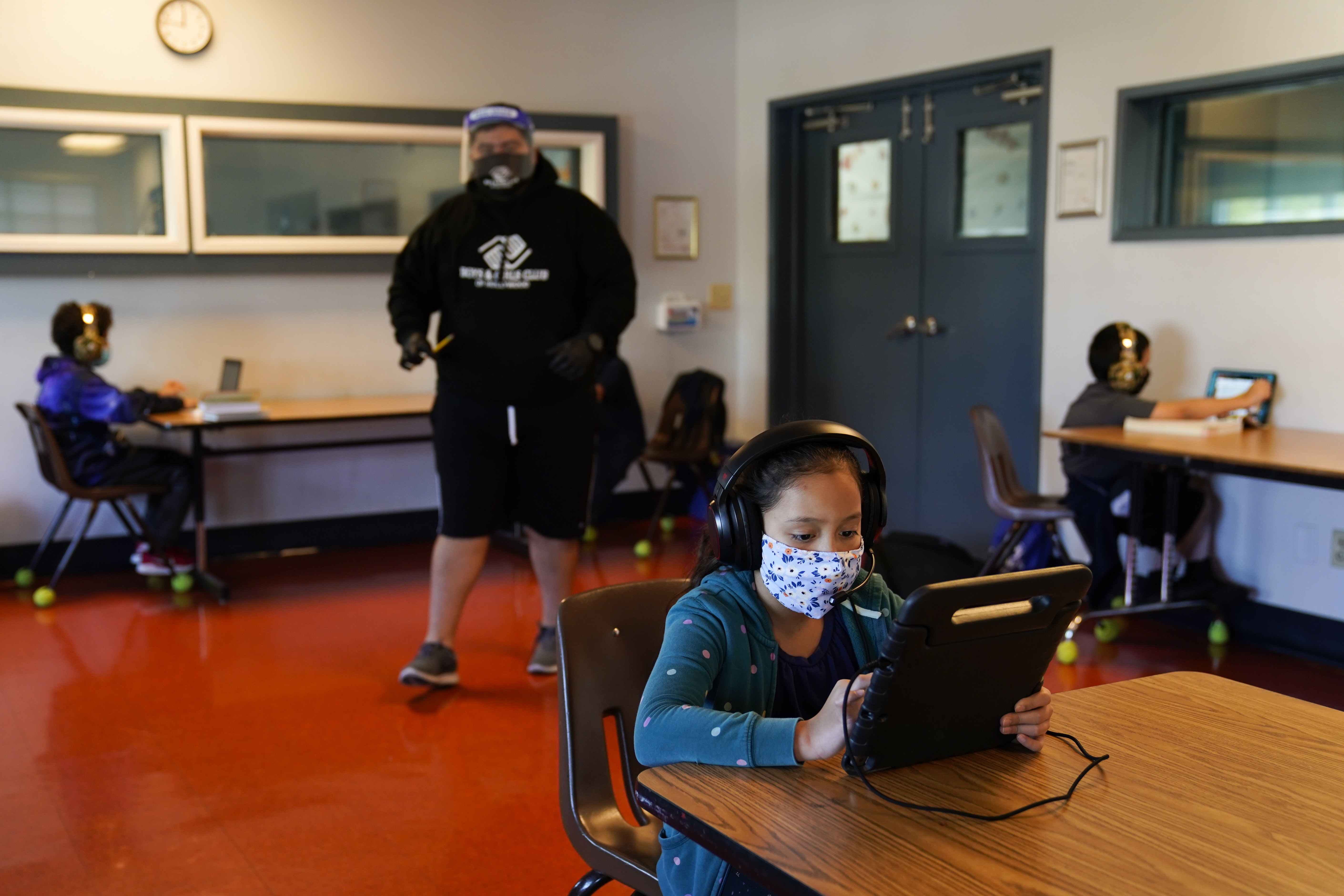

Since then, districts have been in a patchwork of in-person, hybrid, and all-virtual learning models, with plans that can change by the day. Some schools looked for creative ways to serve their students — like by building an outdoor classroom or offering grab-and-go meals as many families rely on school lunches.

But many still worry that the chaotic school year has set kids back in learning and mental health. In a recent survey by UW-Milwaukee researchers, only 15% of families thought their student was learning just as much as in pre-COVID times; one respondent wrote, “I’m tired of arguing with my son and listening to him cry because he is feeling hopeless.” The state also faced a “digital divide” with some students, especially in rural areas, lacking good internet access for their virtual classes.

Students with working parents attend online classes at Boys & Girls Club. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

With teachers now starting to get their COVID-19 vaccines — and research also showing that K-12 schools haven’t been a big driver of coronavirus cases — Evers said in March that schools should be able to reopen for in-person learning. And, to catch kids up, he also suggested having summer school courses or starting up early in the fall might be good options. Still, COVID-19 vaccines haven’t been approved for kids under 16 yet, and it’s unclear whether students will be able to get their shots by the time the fall semester rolls around.

Of course, higher education has also felt the pandemic’s impacts. Some universities saw major outbreaks when students returned to campus in the fall — including UW-Madison, which sent two of its largest dorms into quarantine after thousands of students and staff tested positive. Across Wisconsin, enrollment in colleges and universities fell by around 4% in fall 2020, according to the National Student Clearinghouse; the UW System estimates it has lost more than $300 million in revenue during the pandemic.

Social impact

In the beginning, there were Zooms. As sharing air became dangerous, Wisconsinites looked for new ways to connect and found moments of socially distanced joy: Small outdoor weddings, at-home graduations, virtual happy hours, and remote acts of kindness.

But as the pandemic has dragged on, these efforts haven’t been enough to stave off the mental and emotional toll of a devastating year. As of a January report, more than 40% of U.S. adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depression, with young adults and people of color seeing the most strain. UW-Milwaukee professor Amanda Simanek said that as a social epidemiologist, she’s concerned about the long-lasting impacts of the pandemic’s social effects — from isolation to economic anxiety to the breakdown of social circles.

The pandemic has also highlighted and intensified the deep racial divides that exist in health care. Black, Hispanic, and Native Wisconsinites have gotten sick at disproportionate rates during the pandemic. Just as a wave of protesters raised their voices against racial injustice this summer, the pandemic shed light on how inequality could become a matter of life and death.

Plus, as scientists and public health officials worked to fight off COVID-19, an “infodemic” posed its own threat. Misinformation and conspiracy theories about the pandemic — from masks to vaccines to the origins of the virus — have all run rampant online this past year, and sometimes led people to put themselves or others at risk. Figuring out how to share good science and take the politics out of preventive measures will be key to the future of public health, said Simanek, who helped found the website Dear Pandemic to answer COVID-19 questions.

Economic impact

After the pandemic’s initial economic hits, Wisconsin actually saw one of the strongest rebounds in the country. As COVID-19 cases kept climbing over the summer, though, the recovery had trouble finding its footing. All in all, a recent report estimates that the pandemic has led to the state’s worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

Susan Brown boxes orders to be shipped from Chef Knives To Go, the business she runs with her husband, on Aug. 18, 2020 in Fitchburg, Wis. They say delivery delays that began this spring have prompted them to shift most of their shipping business to FedEx. Wisconsin has seen mail delays — including on delivery of absentee ballots — even before the controversial cost-cutting measures by new Postmaster General Louis DeJoy. (Will Cioci/Wisconsin Watch via AP)

Some industries, like manufacturing, have stayed relatively steady. But others that rely on in-person attendance have taken huge hits — especially food service, arts and entertainment, and hospitality.

Water parks in the Wisconsin Dells sat nearly empty during the spring break season; hotels near Lambeau Field were far from packed as the Packers went fan-free for the regular season; even the Democratic National Convention didn’t bring host city Milwaukee much of a boost after going mostly virtual.

For lots of Wisconsinites, job losses and insecurity in food and housing have all been part of the economic fallout from COVID-19. The Department of Workforce Development saw a flood of unemployment claims over the course of the year, and a backlog at the DWD left many jobless residents waiting weeks for relief.

Even though the state’s recovery remains fractured, some small business owners are feeling optimistic with the pandemic’s end in sight. Innovation may be key to moving the economy forward, experts say, and some Wisconsinites have already stepped up to that challenge over the past year — from a barber taking haircuts to the road, to restaurants crafting distanced dining experiences, to distilleries cranking out hand sanitizer instead of whiskey.

The future

With vaccinations ramping up, case counts on the decline, and warmer weather on the horizon, things seem to be looking up for the Badger State. We could be on the “other side” of the pandemic within a few months, DHS Deputy Secretary Julie Willems Van Dijk estimated — though it’s still hard to say exactly what the other side will look like.

“What I’d love it to look like is we’ve eliminated COVID,” Willems Van Dijk said. “But I don’t know if we’ll get there.” It may be hard to completely wipe out the novel coronavirus, especially given the recent rise of mutated variants, and some infections might still circulate in the future.

Still, as long as we keep up preventive measures for a little while longer, we can hopefully look forward to a point where COVID-19 infections are rare, everyone can get a vaccine, masks aren’t necessary, and we are finally able to see our loved ones without fear. “We’re definitely out of the dark and heading in a good direction,” Simanek said.

For this writer at least, having the finish line in sight is a huge relief. Since moving to Milwaukee during the pandemic, I still haven’t gotten to know my new home without the looming threat of COVID-19. I feel like I’ve been missing out on so many of the things that make Wisconsin special, and practicing my favorite Midwestern phrase — “ope, just gonna sneak right past ya” — just doesn’t have the same punch when we’re already six feet apart.

Like many Wisconsinites, I can’t wait to get back to a sense of togetherness in the year ahead. For now, we still have to hunker down to keep ourselves and our communities safe. But with the first year of COVID-19 behind us, we’ve got plenty of practice with that; and with brighter days to look forward to, we’ve got a light to guide us toward the end of the tunnel.

Here’s hoping for some more precedented times ahead.

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Spectrum News 1 can be found here ***