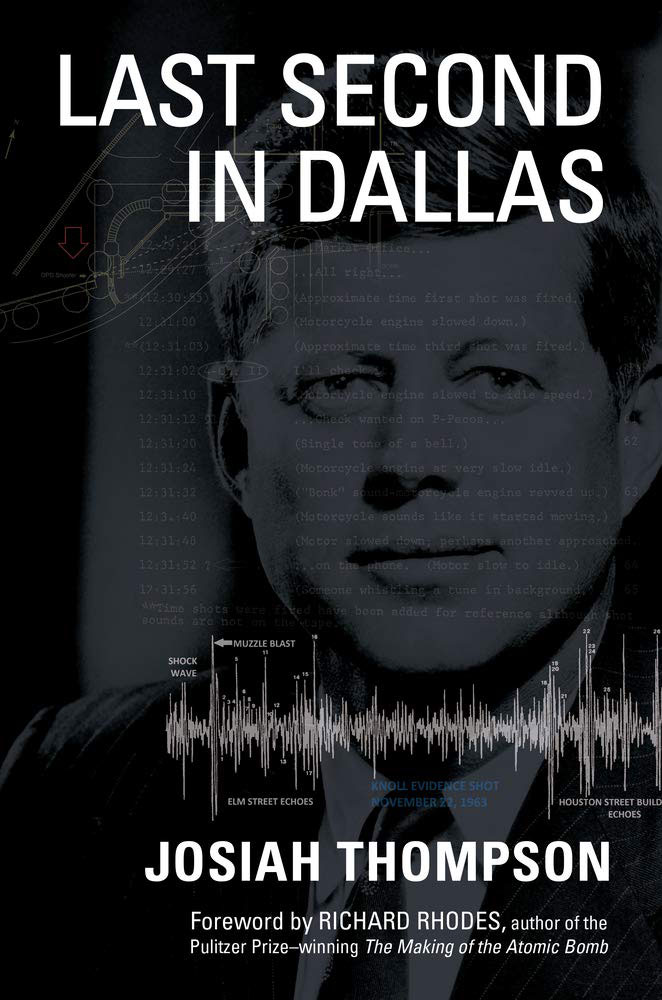

Josiah Thompson’s Last Second in Dallas –

Josiah Thompson

Last Second in Dallas

(University of Kansas Press, 2021)

Josiah Thompson’s Last Second in Dallas is not only a revelatory forensic analysis of the Kennedy assassination, but it is also a troubling and timely book about state science, confirmation bias, and a man by the name of Dr. Luis Alvarez. As an author whose father served at the CDC during the Vietnam War and whose grandfather helped design the bellows of the atomic bomb for the Manhattan Project, I am familiar with stories of how human the scientific method can be. The measurement often does depend on the measurer. But Thompson’s book doesn’t just reveal, from the outside, the shoddiness of the same establishment institutions that gave us Tuskegee, the Warren Commission, and the Iraq War. What’s ultimately remarkable about this book is that the author works closely with those very state institutions, pushing and prodding them from within, participating in an ongoing peer-reviewed dialogue that reaffirms the reader’s trust in the process of scholarship and truth-telling. Furthermore, and even more remarkable, is this: I believe Thompson has solved one of the three great questions surrounding the murder of John F. Kennedy.

The big questions, as far as this reader is concerned, derive from the conflicting reports of the two government commissions on the assassination: the Warren Commission of 1964 and the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) from 1977. The former claimed a lone gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald, killed President Kennedy on November 22, 1963, and the latter suggests the crime was likely a function of conspiracy. One country. One crime. Two reports. Three questions: How many shooters? How did they (or he) do it? And why did they (or he) do it? The brilliance of Thompson’s book rests with a methodology that ignores the sexy and elusive appeal of questions two and three. With no ostensible interest in the role of the CIA, the FBI, Khrushchev, Castro, Lyndon Johnson, Jack Ruby, the Dallas Police Department, or the mob in the life and death of Lee Harvey Oswald, Thompson instead distills these logistical mysteries down to a basic forensic problem regarding how many shots were fired during the visible timeline supplied by the home movie of the killing taken by Abraham Zapruder.

Last Second in Dallas, like Thompson’s first book on the assassination, Six Seconds in Dallas (published in 1967), focuses intensively on the Zapruder film. Like many researchers, this one included, Thompson was baffled by the exclusion of Zapruder from the 888 pages of the Warren Commission’s report. In an effort to correct the government’s glaring omission, Thompson’s first book studies the film closely and pays particular attention to the movements of the president’s body as he approaches and passes frame 313. However, with the assistance of new technology, Last Second in Dallas performs what it promises: a closer look at those frames and the last second of the murder. But in addition to this refined eye on the crime, Thompson also provides the reader with an ear, an acoustic analysis of the assassination enabled by the audio files of the event and a 21st-century digital analysis of those files.

Enter “the distinguished American scientist,” Luis Alvarez, the “Nobel Prize winner in Physics for 1968.” Alvarez, like my grandfather, took part in the Manhattan Project. Anyone who ever suggests America can’t keep a secret need look no further than the private leaks and the public silence regarding that state scientific endeavor. But Thompson pays no attention to tantalizing whispers or historical rabbit holes. Instead, he focuses on the public record of scientific debate spearheaded by men like Alvarez and writes, “It is no overstatement to say that in the whole tangled history of the case, no single individual ever played a more central role in preserving a mistaken view of the shooting.” Now what seems important to mention here is that it was Alvarez, in scientific scholarship, who first challenged Thompson’s 1967 claim that there were multiple gunmen. Furthermore, it was also Alvarez, again through the engines of American scholarship, that attempted to refute Thompson and the House Select Committee after they released their conclusions affirming Thompson’s argument for multiple gunmen based on the acoustic evidence provided by Dallas Police radio recordings of the event. As one travels through the annals of the debate between the Warren people and HSCA people, in many ways the conversation boils down to Alvarez versus Thompson.

What a tragedy on top of tragedy we would have if Thompson had yielded to the goads of gossip, grudge, and insinuation, and made his book a personal attack on Alvarez. Instead, what we get from him is a voice that is generous, collegial, and deferential, constantly willing to stipulate patriotic and ethical motives for the actions of his critics. As I read Last Second in Dallas, I kept waiting for the howl and the rage, the whisper and the cheap shot, what one encounters so often in the books by “the buffs,” as Thompson calls them. But the author, as a Yale educated scholar publishing through University of Kansas Press, both honors and complicates his relationship to the academic peer-reviewed process by sticking to the facts and the story of two forensic investigators: himself and Alvarez. One came of age during Vietnam while the other cut his teeth during World War II. One challenges the government’s first official narrative of the Kennedy assassination, while the other supports that first state story. At one point, Thompson quotes Jean-Paul Sartre who wrote that, “we live our lives as if we are telling ourselves a story, and we live surrounded by the stories of others.” Like the rest of America, Thompson and Alvarez lived their lives while surrounded by competing stories about the American state and the assassination of that state’s 35th commander-in-chief. Thompson, through discipline and humility, accomplishes a rare feat in Last Second in Dallas. He offers a new story; an original analysis supported by 21st-century science.

I do not read the book reviewer’s job to be the simplification of a complex argument, even though some species of that task is always part of the genre. In this particular case, I would like to be clear that the success of Thompson’s argument depends on the reader’s willingness to engage with rigorous scientific analysis. This is the blessing and the curse of Last Second in Dallas. Thompson’s book has a number of entertaining moments, like cameos from Geraldo Rivera and an anecdote about a particular gentleman’s magazine that plays a surprise role in shaping the research of Luis Alvarez. Thompson pays tribute to the work of other contributors to the investigation, like the novelist Don DeLillo, and Thompson’s friend and fellow researcher, Sylvia Meagher. But, ultimately, these asides seem designed to give the reader a chance to breathe between Thompson’s relentless and detailed confrontations with graphic forensic evidence. This is a serious book driven by serious science released to an American audience whose appetite for such rigorous discourse seems questionable here in what some call the “post-truth era.” In a historical moment where disinformation trolls and conspiracy “buffs” like QAnon regularly deploy simple and fantastic theories of the Kennedy assassination to support what Shoshana Zuboff calls “epistemic chaos,” Thompson offers readers a counternarrative insofar as he gives them a thoughtful, methodological argument populated with tables, data, and the clearest photographs of the Zapruder film I have ever witnessed. To be taken, step by step, through the history of JFK assassination research, from 1964 through 2020, was thrilling and illuminating for this reader. To study the public and private conversations between the Alvarez school and the Thompson school, particularly when it comes to the reappraisal of the acoustic data, is to get a privileged glimpse behind the curtain of a scientific community that is often, ironically, treated as sacred. And yet, praise science as we might during this time of pandemic, how many readers are actually prepared to engage with its method?

Readers should never worship at the altar of the white lab coat. Like Stanley Milgram and his famous experiment on the relationship between obedience and authority, Thompson puts the coat itself under the microscope. Science can be fallible. Scientists are human beings. They can tell stories and fall under the sway of their own mythos, as well as that of their state’s. For a number of reasons, the story of the Kennedy assassination still speaks to readers across generations who are concerned that America has lost its way, which is to say, its relationship with the truth. What Thompson’s narrative contributes to the nation and the field is original forensic data, and the most comprehensive, up-to-date study ever published on both the science and the scientists behind the scene of the investigation into the assassination of President Kennedy.