Pieter’s Corner: sense of conspiracy theorists

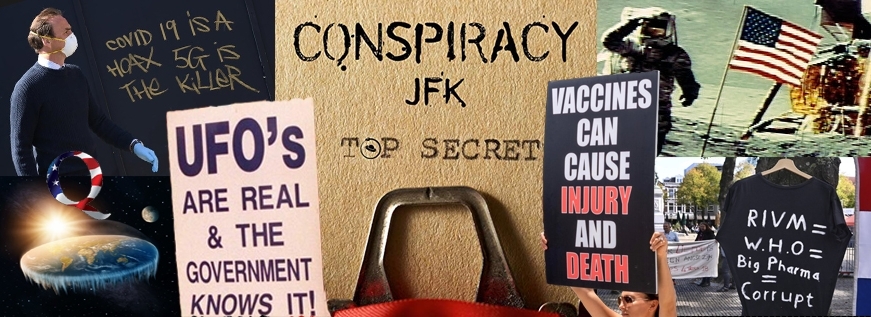

Climate change is made up, the secret services murdered Pim Fortuyn and JFK, and the moon landing was a fake show. Conspiracy theories are of all times, providing sensation and entertainment, but also unrest and fear. The corona pandemic is new fuel for conspiracy theorists who set fire to 5G masts, accuse the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) of lies, and undermine vaccination programmes. Are these far-fetched theories to be taken serious? Are they harmful or useful for society? Our social scientists give their point of view:

Pointing fingers does not beat fear

– Jackie Ashkin, CWTS

When it comes to conspiracy theories, we often hear ourselves asking, ‘How can someone believe that?’ The anthropological injunction to ‘take people seriously’ might lead us down a different line of question. What would happen if, instead of asking how someone believes in something, we asked why they believed in it?

Conspiracy theories are nothing new, though a number have gained significant traction in recent years. Historically, conspiracy theories can be understood as a sign of the times – during World War II, sweeping economic changes across the American South prompted rumors amongst whites of an impending black-lead revolution. White women interpreted their difficulty retaining black household staff as a sign of domestic insurrection, when in reality they were moving to better-paying industrial jobs in support of the war effort. While the rumors were ultimately false, the race-based fears that inspired them were very real.

Taking people seriously, then, does not necessarily mean taking them literally. Whether talking about the Illuminati or the moon landing, chemtrails or extraterrestrials, conspiracy theorists today are often charged with irrationality and dismissed outright for the absurdity of their claims. This dismissal is problematic not least because it misses the point. Recent scholarship from colleagues at Erasmus University Rotterdam and KU Leuven suggests that conspiracy theorists are expressing their epistemological insecurity – in other words: conspiracy theorists critically analyse their worlds, and what they find is a culture where (scientific) authority can be contested, and traditional knowledge-making institutions (like universities) are no longer worthy of their trust.

To social scholars of science and technology, the notion that scientific knowledge is embedded in political, economic, historical, and social practices hardly seems new. In Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer’s (1985) Leviathan and the Air Pump, the authors question the dogmatic inevitability of experiments as we know them today, and in Laboratory Life (1986), Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar explore how facts are constructed through the scientific process. In making the familiar strange, Latour and Woolgar demonstrated the role of social norms and institutional contexts for knowledge production. Conspiracy theorists today are not as far off the rails as we might like to believe.

Rather than pointing fingers, we must take conspiracy theorists – and their theories – seriously. Regardless of the veracity of their theories, the fears triggered by a culture of competing knowledge claims and untrustworthy institutions are very, very real.

On the cultural logic of conspiracy thinking

– Peter Pels, Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology

‘Just because you’re paranoid, doesn’t mean there isn’t someone after you…’. The famous joke plays upon the expectation that suspecting a conspiracy is pathological – not logical. I mostly agree: both sociology and social anthropology suggest that humans are neither smart nor consistent enough for a minority to plot against large numbers of others permanently and with success – except in novels, film scenarios, or political propaganda. Successful and disastrous conspiracies occur, but they are fleeting events: the study of genocide has, unfortunately, all too often shown malevolent elites to engineer temporary mass insanity by dehumanising so-called Jews, Muslims, Hutus or Tutsis.

Longer-lasting and consistent pathologies are only made possible by a persistent cultural logic that is widely shared and can carry the burden of ‘truth’. Transatlantic slavery produced such pathological representations of reality after 1525, when European profiteers initiated the practice of selling those with a darker skin as proto-capitalist, less-than-human laborers. From the early 19th century, such racial hierarchies, despite lacking both proof and consistent methodology, became a widely accepted part of the science of biology. As sociologist Karen Fields argued, the existence of those differences was supported, long after the abolition of slavery, by a ‘racecraft’ as believable, and as paranoid, as witchcraft.

The long-term cultural logic behind today’s avalanche of conspiracy thinking is different. Based in individualism, both left-wing and right-wing developments supported it. Remaining largely unnoticed during the 19th-century battles between scientific and religious authorities, cultural democratisation slowly generated a modern kind of gnostic knowledge – a trust in nothing but personal experience, coupled to a mistrust of authoritative knowledge (whether the elite’s Christian faith or its scientific reason). Its sources were multiple: the global success of 1950s American Ufology, the mainstreaming of 1980s ‘New Age’ from the margins of Theosophy and Spiritualism, and the ‘Moral Majority’s’ Evangelical beliefs in an impending Apocalypse (among others) reinforced earlier traditions of nationalist paranoia about internal enemies and migrants and the make-believe of advertising and public relations.

Anthropologists Susan Harding and Kathleen Stewart demonstrated that the slogan of the TV-series The X-files (1993) – ‘Trust No One. The Truth Is Out There’ – has become mainstream in the USA. I believe this logic has already crossed and re-crossed the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Pacific, to emerge as a global political pathology today.

Conspiracies: the role of religiosity

– Simon Chauchard, Political Science

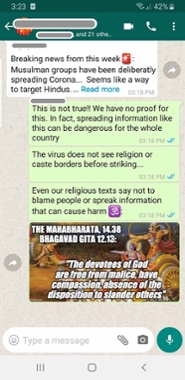

Was COVID-19 made in a lab? Are members of minority communities sneezing in unison to spread the virus? Did Bill Gates insert a microchip in the newly developed RNA vaccines? These are examples of viral conspiracies surrounding COVID-19 in developing countries such as India, Tanzania and Madagascar.

Research on online misinformation has thus far focused on its political and psychological drivers in Western democracies. However, the ability of such pernicious misinformation to spread is arguably higher in developing countries, where citizens have lower levels of digital literacy and where information is shared via encrypted applications such as WhatsApp. These conspiracies matter. Beliefs in health-related conspiracies may for instance lead people to ignore best practices like social distancing. Beliefs in narratives that scapegoat minorities can in turn pave the way for polarization and violence.

In recent research, Sumitra Badrinathan and I quantify the prevalence of these COVID-related conspiracies in a representative sample of the Indian population, and find alarming high rates of prevalence for each of the already viral conspiracies we test for. A majority of Indians we question for instance declare believing absurd or vague statements such as “Foreign Powers Are Deliberately Causing The Spread Of Coronavirus” or “85% of Muslim Communities Refuse COVID-19 Tests For Religious Reasons” to be either true or definitely true.

Scholarship on US politics often attributes belief in conspiracies to what is called partisan motivated reasoning – where individuals interpret information through the lens of their party commitment. We show that the drivers of belief in conspiracies may also owe to other factors, at least in the specific context we are interested in (India), but potentially beyond. While we show belief in these conspiracies to be associated with support for the ruling party in India, we more generally find a very strong and continuous association between religiosity and these beliefs: that is, the more religious our respondents (as measured by a set of questions about their religious practices), the more likely they are to believe in the conspiracy stories whose veracity we ask them to evaluate. While this is in no way a causal finding, it leads us to believe that potential policy interventions should tap into religiosity to address the problem.

This is what we do in a subsequent intervention, in which we evaluate the effect of atypical, religion-infused corrective messages in WhatsApp groups (the social medium of choice in India). We find that exposure to these “religious corrections” improves the overall efficiency of corrective messages – that is, they further decrease beliefs in conspiracies. These effects exist across all sub groups of respondents, regardless of their degree of religiosity. This constitutes additional evidence for two ideas motivating our research: that peer corrections make a difference and that religiosity may be leveraged to correct misinformation. This suggests that corrections may need to be tailored to their audience, and more generally, that misinformation research ought to better take religiosity into account.

The toll of misinformation

– Andrea Reyes Elizondo, CWTS

The spread of conspiracy theories is a fascinating phenomenon, for me as a researcher as well as a friend. Like urban myths, these theories reflect our fears and taboos. A marked difference is that conspiracies fulfill the need to explain complex topics. This need may arise due to a deluge of information, a lack of critical skills, unclear information from authorities, and/or astroturf propaganda.

While following media across two continents, conspiracy theories concern me on two levels: family and friends believing doubtful information endangering their health, and conspiracies slowly eroding trust in institutions. In the former, relatives could refuse a vaccine due to Plandemic; in the latter, people could mistrust official standards for example for drinkable water.

None in my family has turned antivaxx, although it has taken me many hours of reviewing WhatsApp videos and audios and providing commentary. Sadly, I have “lost” a friend down the rabbit hole. In the 2008 crisis they lost considerable savings. Seeing that others benefited, made them believe it was orchestrated. When the pandemic was declared and people did not drop dead on the street, they suspected foul game. After a few clicks on the web they were convinced COVID-19 was not what we were told: the deaths are exaggerated and this is all a plot to control us while making money. Worryingly, the story grew bigger: from Bill Gates determining what water we drink in the Netherlands to the Federal Republic of Germany not really existing (a common far-right trope).

While there is a tendency to laugh off these beliefs or concerns, I can no longer connect with my friend as before. They have seen the light – us – while I have not – them. Many of the COVID-19 and QAnon conspiracy claims are Elders of Zion recycled tropes, yet I have failed to create a dialogue: I have listened and, as a researcher, tried to present facts and context to no avail.

The pandemic has been a festering ground for conspiracies: an overabundance of information, a lack of clear communication from most governments, media outlets blinded by ‘bothsidesism