The Untold Story of the CIA’s MK Ultra: A Conversation with Stephen Kinzer

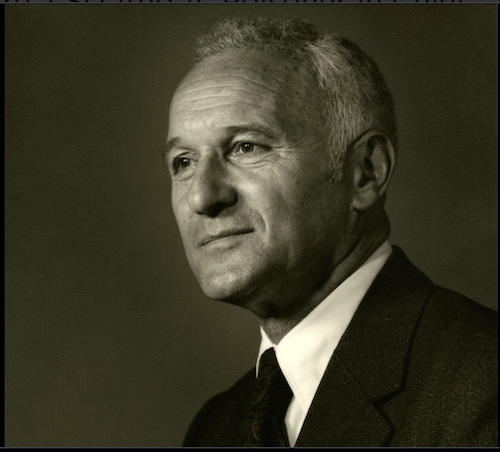

FROM ITS INCEPTION, Project MK Ultra was a program shrouded in mystery. At its apex in the mid-1950s, only a handful of CIA personnel even knew of its existence. Yet MK Ultra was dubbed “Ultra” for a reason. For the Agency’s highest echelons, the program promised a key for achieving victory in the Cold War and complete world domination. Its objective: To appraise the possibilities of mind control, of bending a subject’s consciousnessto act against their own will. Historian Stephen Kinzer’s 2019 book, Poisoner in Chief: Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA Search for Mind Control, examines the project’s eponymous, little-known mastermind: a Caltech biochemist and expert in biological warfare who was handpicked by CIA director Allen Dulles to run the covert program in 1953.

Gottlieb was an atypical choice for the CIA. He didn’t attend Groton or Princeton, or work for a Wall Street law firm, but came from working-class Jewish roots in the Bronx. Gottlieb was spellbound by LSD early on. After getting glimpses of its use in early studies, he became convinced that the Soviet Union was stockpiling LSD for mind control experiments. He soon urged the CIA to buy the world’s existing supply of LSD from Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Switzerland, the employer of its discoverer, Albert Hofmann. Driven by Gottlieb’s commitment, LSD soon became MK Ultra’s drug of choice, and within a few years, an extensive network of research projects had been set up at hospitals and universities throughout the United States.

The immediate goal was to find a drug that could act as a truth serum for use in espionage. A Soviet agent could be dosed with LSD, the theory went, and induced to confess government secrets. Yet for someone seeking to control minds, it’s surprising that Gottlieb’s research was itself so uncontrolled. On numerous occasions, he surreptitiously dosed his CIA colleagues and informed them only several hours later. In other cases, Gottlieb’s tests were a direct continuation of the Nazis’ most horrific medical experiments, involving a combination of exotic psychoactive drugs, sensory deprivation, electroshock, isolation, verbal abuse, and various forms of torture. The objective was to obliterate consciousness so that a new mind could be implanted in the subject. After 10 years of unsuccessful research, Gottlieb conceded in a 1963 CIA memo that mind control was impossible.

Poisoner in Chief marks Kinzer’s most ambitious project yet. A widely respected New York Times journalist and historian, Kinzer has extensively covered the history of the CIA, writing books about the Agency-sponsored coups in Guatemala and Iran and a highly praised joint biography of John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles. But writing about Gottlieb was a different sort of challenge. An elusive character, the man lived entirely under the radar, and very little is known about his personal life and clandestine CIA career. What’s more, when Gottlieb retired from the CIA in 1973 — two decades after MK Ultra’s foundation — he and director Richard Helms attempted to destroy the project’s entire documentary archive, further complicating the task of historians. Building on John Marks’s 1979 book, The Search for the ‘Manchurian Candidate’, Kinzer manages to piece together the missing parts of Gottlieb’s life — and the man who emerges is stranger than one could ever have imagined.

Likely inspired by his own prodigious use of LSD, Gottlieb was a hippie before the hippies: he meditated, lived in an eco-lodge without indoor plumbing, grew his own vegetables, and rose before dawn to milk goats. He and his wife raised four children, and even shared a life-long passion for folk dancing. Countering the bucolic peacefulness of Gottlieb’s family life is the sheer moral depravity of the program he oversaw. A bizarre and subterranean world, MK Ultra is a conspiracy theorist’s dream still imbued with unreckoned detail: how many victims the project claimed, its true stretch throughout US power politics, its legacy beyond 1973, and other blanks that will likely never be filled.

Poisoner in Chief is a biography of Dostoyevskian proportions. Gottlieb emerges as a tortured soul, penned in by personal compunction and a twisted sense of patriotism. He sought desperately to atone for his sins during the last three decades of his life, before dying, some have speculated, by suicide. Gottlieb’s trip was over, and we’re still making sense of it.

¤

JAMES PENNER: Before you wrote Poisoner in Chief, many people had never heard of Sidney Gottlieb. The Wikipedia page on him was pretty brief, for example. How did you stumble across him? And why did you decide to write a biography about him?

STEPHEN KINZER: First of all, your comment that not very many people know about Sidney Gottlieb is an understatement. Sidney Gottlieb lived his entire life in total invisibility. My book is essentially the biography of a man who was not there. That’s what made writing it quite demanding, but also interesting and challenging at the same time. Let me put it his way: I think I have discovered the most powerful unknown American of the 20th century, unless there was somebody else who operated a network of torture centers, lived in absolute secrecy, and had what amounted to a license to kill issued by the United States government. He is so obscure that, while I was writing this book, I happened to run into a retired director of the CIA at a local café. And I went up to him and said, I am writing a book about a figure in the CIA. And he said, Who’s that? And I said, “Sidney Gottlieb.” And he said, “Never heard of him.” Wow. This was a former director of the CIA. And I believe him. I think he was telling the truth. He probably had never heard of him.

I wrote a biography of John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, the Secretary of State and the CIA director, respectively, in the 1950s. In the course of writing that biography, I wrote about the Dulles brothers’ effort to assassinate the prime minister of the Congo in 1960. As a part of the assassination plot, the CIA actually sent poison to the Congo; it was delivered to the CIA station chief there. As I filed that detail in the back of my mind, I began to wonder about that story. So, wait a minute now. The CIA made poisons to kill a foreign leader, so it must have been done by a person, a scientific expert, not just a CIA agent. Somebody at the CIA was making poisons. And then I discovered that this man was Sidney Gottlieb, and it soon dawned on me that the one thing that you could find out about Sidney Gottlieb — that he was the poison maker — was actually not the most important thing. Making those poisons was just the job of a sophisticated pharmacist. If it hadn’t been Gottlieb, someone else could have done it. But I came to understand, as I was poking around in the Gottlieb story, that there was another piece that was way bigger than the poison piece, and that was MK Ultra. Once I understood the dimensions of what that was and how little was publicly known, I realized that this is the great untold story, and untold stories are what I am always looking for.

JAMES PENNER: I enjoyed reading Gottlieb’s account during the Congressional Hearings on MK Ultra of his own LSD trip. And I’ll just read it for you: “I happened to experience an out-of-bodyness, a feeling as though I am in a kind of transparent sausage skin that covers my whole body and it is shimmering. And I have a sense of well-being and euphoria for most of the next hour or two hours, then it gradually subsides.” How could someone who had these euphoric and benevolent experiences participate in horrible experiments with LSD?

Gottlieb was the first LSD maven. He was fascinated by LSD. The reason was that he thought the drug might be, as one of his colleagues put it, “the key that could unlock the universe”: in other words, it would finally give us the key to mind control. In 1953, Gottlieb arranged for the CIA to buy the entire world’s supply of LSD. He brought it to the United States from Switzerland. And he began using it in two kinds of experiments. Gottlieb, himself, loved LSD. By his own account, he took it more than 200 times. He must have been aware of its effect on consciousness and reflection. He did a lot of things that fit into that category: he studied Buddhism; he wrote poetry; he meditated. But at the same time, he was able to use LSD in horrific and coercive ways.

He wanted to see what massive doses of LSD might do to people’s minds. Bear in mind that Gottlieb was working on this premise before. He believed that, before you can find a way to implant a new mind into someone’s head, which was his goal, you first have to find a way to destroy the mind that’s already there. How do you do that? Gottlieb created hundreds of experiments having to do with sensory deprivation and extreme heat and cold and electroshock and combinations of all sorts of drugs to find out if there’s a way to destroy a human mind.

ED PRIDEAUX: You know, 200 acid trips is a lot. Perhaps this is too speculative, but do you sense that he became somewhat detached from reality as he got more into MK Ultra and his number of LSD trips accumulated?

In one of the speeches I gave while I was promoting this book, I said that Gottlieb, in the end, admitted that brainwashing is not possible. And a professor in the audience raised her hand and said, “I want to contradict you, you said that Gottlieb failed to brainwash anyone. But that’s not true: he managed to brainwash himself.” That was the only real brainwashing success of MK Ultra. They were able to brainwash themselves into believing that fictional concepts of hypnotism and mind control could be made real and weaponized for the Cold War. To have fallen for that really is a form of brainwashing. Could Gottlieb have conceived some of these completely bizarre experiments that he carried out while he was on LSD? Was he on LSD while he was watching people being tortured and killed? We don’t know, but it’s kind of a chilling thought.

ED PRIDEAUX: Another question I have relates to the Nazi connection, the fact that the CIA hired many ex-Nazi doctors who tortured people during World War II, including experimenting with mescaline on prisoners at Dachau. But Gottlieb was Jewish. How the hell did he compartmentalize that? Was he conscious of this contradiction?

He could not have failed to recognize it. Gottlieb was the son of Jewish immigrants who came to the Bronx from Central Europe. If they had not emigrated, if they had remained in Central Europe, quite possibly they would have been swept up in some Nazi roundup and young Sidney might have become a victim in one of those grotesque experiments in a concentration camp. Nonetheless, he didn’t seem to have any hesitation about working shoulder to shoulder with the very same Nazi doctors who carried out those experiments.

I can imagine different ways he might have justified that to himself. But that’s only my imagination. It may be part of the same reason he could justify killing people in his experiments. That is, “We are facing a life-or-death threat. We don’t have the luxury to be ethical and legal.” I think this is actually one of the great lessons of MK Ultra. One of the greatest motivations or justifications for committing immoral acts is commitment to a great cause. Patriotism is one of the most seductive causes of all. And when you can convince yourself that your nation is under imminent threat, it makes sense to relax some of your moral and legal standards.

JAMES PENNER: Gottlieb knew a lot about poisons, and he was familiar with the scientific method. So why, after the death of his colleague Frank Olson in an MK Ultra experiment, didn’t he learn from his mistakes? It seems like he was not a very good scientist because he kept repeating the same mistakes over and over again.

You’re absolutely right. Gottlieb was a terrible scientist. His experiments were not conducted with scientific rigor. Many of the people that he had as operatives carrying out these experiments abroad didn’t speak foreign languages. They were not trained in psychology. They didn’t have the tools to understand what was happening, and I think this is one of the things you really can wonder about with Gottlieb. He had a PhD in Biochemistry and he was obviously quite brilliant. The only thing I can guess is that he would have thought to himself, “The scientific method and traditional ways of guaranteeing accuracy in scientific research are fine, but I’m off in a new world. I’m trying to discover something that’s never been discovered, and therefore I can’t follow the rules that science dictates.” Actually, I think this was his calculation, but it was very mistaken because no matter what you’re looking for, even if it’s something crazy like mind control, you should have some kind of scientific parameters for your experiments. And Gottlieb rarely did.

JAMES PENNER: You argue that Gottlieb was not a sadist, but many of his experiments suggest otherwise. Could you explain why you think he’s not a sadist?

No, I can’t explain it. Maybe he was. My impression of him is that he felt that what he was doing was distasteful but that the work was absolutely necessary. In fact, I have a quote in the book from one of the few pieces of testimony that have been released in which he says, “I want this committee to know that I found this work very difficult, very unpleasant, but very necessary.” Did he relish the idea of inflicting suffering? I don’t know. Was I too quick in my book to say he was not a sadist? Maybe. I leave it to the reader. I don’t want to live and die on that hill.

ED PRIDEAUX: One thing I found really curious during my reading about the MK Ultra program, and even during our conversation, is that my emotional responses have been either morbid curiosity or humor. I can react with, “Whoa, that’s crazy!” but, actually, these stories are extremely tragic. What was your emotional reaction to these stories? Did you feel the same way?

This is my 10th book. And in my books, I have reported things that have shocked many readers and have surprised me, too. But this is the first time I have been shocked. I still can’t wrap my mind around the fact that there was such a project as MK Ultra and such a person as Sidney Gottlieb. I can’t fully grasp the fact that this really happened. While I was writing the book, I was surrounded with this horrific evil. I felt like I should be burning sage right here in my own office next to the laptop. It was a very disconcerting journey, particularly because there’s so much mystery, not just about the project, but about Gottlieb himself. Here’s a guy who was deeply spiritual and, in his private life, devoted to charity. Yet during his work life he carried out the most intense and extreme experiments on human beings that have ever been conducted by any officer or agent of the US government. How do we keep those two sides together? I don’t know.

I do know this: after Gottlieb retired, he became consumed by what he had done. The rabbi that he worked with in Virginia after he retired told me that she tried to get him to open up. She said it was like there was a great elephant that he wouldn’t face in the room, but he never would. The journalist Seymour Hersh went out to visit Gottlieb during this period. And he told me that he was a destroyed man. He was wracked with guilt. If he had been a Catholic, he would have gone to a monastery. Since my book came out, I’ve heard from some people who knew Gottlieb during this period, and one of them said, when I knew him, he was in his “atonement phase.” In his comments to his lawyer and the Congressional testimonies that he gave, he never expressed any regret for anything. Yet these stories suggest that he may have been plagued by some feelings of guilt or regret in his later life.

JAMES PENNER: Could you talk about MK Ultra’s relationship with fiction? How has it become a popular jumping-off point for many writers and filmmakers?

What I find absolutely fascinating is that MK Ultra and its search for mind control was built on a fantasy that comes in part from fiction. But then MK Ultra, once it was revealed, spawned a whole genre of fiction itself. There are movies and books referring to MK Ultra. There are songs about it. There was even a strain of marijuana that won the Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam a few years ago called “MK Ultra” because of its effect on your mind. We now have the whole Jason Bourne series. Kathy Acker, so many writers, have talked about MK Ultra and the idea of mind control. It’s entered into our conspiracy culture.

JAMES PENNER: I have a question about mind control and whether it’s possible to modify someone’s behavior. Gottlieb concluded that mind control was impossible by the early 1960s. What about Stockholm Syndrome, however, and the case of Patty Hearst? When she was kidnapped, Hearst was an undergraduate at Berkeley in the mid-1970s, a girl from a wealthy family. And after torture and sensory deprivation, she becomes a militant bank robber and member of the Symbionese Liberation Army. Doesn’t that suggest that mind control is possible — not with LSD, but through other means perhaps?

I would offer a somewhat different approach. When Gottlieb concluded sometime around 1960 that mind control is a myth, he was probably right. He tried everything and concluded that there’s no such thing as mind control: you can’t seize control of a person’s mind and make them do something they don’t want to do. And, in fact, psychologists like Karl Menninger had been telling him this, but he didn’t want to believe it. Here we are now, however, we’re half a century later, the developments in artificial intelligence and computer technology are so advanced and are proceeding at such a pace. That technology may be merging in a way that Gottlieb could never even have imagined. We may now be on the brink of discovering new techniques that would have been unimaginable in his era, and to me that is quite frightening.

JAMES PENNER: And what do you think these new techniques are?

Get yourself inside the mind of DARPA [Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency], or the Chinese Secret Service, or other secret services, and ask them. How can you use artificial intelligence, or cyber techniques, to penetrate the human mind? Don’t ask me, but I think there are people who know a lot more than I do who are thinking about this now, and that frightens me.

JAMES PENNER: Could you talk more about the issue of what might be called “domestic blowback,” the idea that the CIA indirectly helped create the counterculture, the hippie movement, and a lot of the antiwar movement? What do you make of that paradox?

It is certainly Gottlieb’s most unexpected legacy. If you’d asked him during the 1950s, “What do you think you might be remembered for?” I don’t believe he ever thought, “I’ll be remembered as the guy that turned on the Grateful Dead and Allen Ginsberg.” When I was doing my research, I came across an interview John Lennon gave where he was asked about LSD. He answered, “We must always remember to thank the CIA and the army for LSD.” Now, John Lennon had never heard of Sidney Gottlieb. Nobody had. But if he had heard of Gottlieb, he would have said, “We must always remember to thank Sidney Gottlieb.” It truly is a remarkable contradiction, or a curiosity of modern history, that the CIA was responsible for bringing LSD into America, and if you unravel everything that LSD meant in the ’60s, its effect on the counterculture and on the culture wars that are still continuing today, that’s quite a remarkable fact.

Now, would LSD have ultimately found its way into the United States without Gottlieb? Probably. Would somebody else have figured out that it could be a recreational substance? Probably. Would it have been used in coercive experiments? Maybe not. The idea that this drug could be used to torture people was something that Sidney Gottlieb came up with and that violated everything that Dr. Hofmann and the other originators of LSD believed in.

ED PRIDEAUX: If you had met Sidney Gottlieb, what might you have asked him?

To me, the great mystery is how Gottlieb fit together his advanced, sophisticated, cosmic, compassionate consciousness with the experiments that he carried out, which were essentially just medical torture. How do you put that together in your head? I think that would be the big question that remains at the end of my book. That’s the one question I couldn’t answer. I said earlier that I don’t speculate in my books, but at the very end I do kind of break out a little bit and try to offer some suggestions. I’m curious about a lot of the details of his sub-projects, but the biggest question is, “How could you have justified this to yourself, not only as a human being, but as a human being who was so loving and so good-hearted? How could you have been such a warm-hearted torturer?” We don’t put those things together normally.

JAMES PENNER: After doing the research and writing this book, do you feel like you know and understand Sidney Gottlieb? Does his life make sense? Or does he still remain an enigma?

I lived in this little room for two years with Sidney Gottlieb. I think I probably know more about him than any living human, except for members of his own family. I actually had to guard myself against being too forgiving. Because I got to know him so well, I felt like I didn’t want to be too harsh on him. But then I went back and remembered what he had done. And that’s when I put the word “heinous” into the conclusion, to make clear that I understood the depths of depravity into which he sank. Nonetheless, although I do feel I got to know him, I definitely still feel that he’s an enigma. He’s an enigma to me. And I still can’t answer the question of how such a person could have done such horrible things. In order to answer that question, the kind of background that I have, which is in World Affairs and International Relations, is not sufficient. It’s a question that goes to the heart of human psychology. And I would love to find someone with a deep understanding of that subject who could read my book and then try to give me an informed psychoanalysis of this bizarre and mysterious figure.

¤

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).