Big Tech Is Still Profiting From 9/11 Conspiracy Theories, 20 Years on

As the 20th anniversary of 9/11 approaches, several large tech companies are still making money from widely-debunked conspiracy theory content about the terror attack that is distressing to survivors and families of the victims.

YouTube, Google, and Apple are all still allowing users to rent or purchase conspiracy theory films like Loose Change on their platforms despite warnings from government officials, experts, and survivors that it hinders proper education about what happened.

The past 12 months have brought a reckoning for America’s tech giants. The de facto role of the likes of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Twitter as arbiters of the national discourse is under increasing bipartisan scrutiny by the media, politicians, and voters.

This scrutiny is driven by concerns about the incessant dissemination of “fake news,” conspiracy theories, and harmful misinformation on these transnational platforms.

D.C. lawmakers hauled leaders of the country’s tech giants in front of Congress to explain themselves.

Most of the biggest platforms have removed many conspiracy theory and misinformation accounts, and several even kicked off former President Donald Trump over his continued false claims of electoral fraud.

Election conspiracy theories, the rise of QAnon, the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, and the coronavirus pandemic have all forced Silicon Valley to act.

Lee Ielpi is a former New York City firefighter whose son Jonathan, 29, died when 2 World Trade Center—also known as the South Tower—collapsed on 9/11.

Ielpi told Newsweek he finds it “troubling” and also “very interesting” that major companies still allow 9/11 conspiracy theory content: “It promotes hostility, it promotes hatred.”

Ann Van Hine’s husband Bruce was also a New York City firefighter who died in 2 WTC. “It’s all gonna come down to money, whether they can make money off of movies, or documentaries or docudramas,” she told Newsweek.

Loose Change is arguably the most famous and influential content to come out of the 9/11 “truther” conspiracy movement. It was viewed more than 10 million times on Google Video within just a few months. Countless pirated copies swelled its audience further.

The documentary was first released in 2005 and has undergone significant revisions in subsequent re-releases.

Such was the impact of the film that the State Department even released its own fact-check, saying the documentary was founded on “poorly thought-through misimpressions and uninformed speculation.”

Overall, State said the film “is researched very shoddily, making numerous mistakes of fact and judgment” but also that none of its shortcomings “prevented it from becoming extraordinarily popular.”

Later versions of Loose Change did not include some of the most extreme claims made initially, such as that a missile rather than a plane hit the Pentagon, and the planes that hit the World Trade Center may have been guided with remote control technology.

But the later editions of the discredited documentary remain true to the original Loose Change ethos of heavy skepticism about the official 9/11 narrative, still hinting at government involvement and a broad cover-up of the “truth.”

One suggestion that remains constant through the various iterations of Loose Change and 9/11 conspiracy theories more broadly is that controlled demolitions brought down the WTC towers, not the impact of two passenger planes and subsequent intense fires.

Loose Change includes an interview with physicist Steven Jones, who claims there was nano-thermite residue found in the rubble of WTC 1, 2, and 7.

Conspiracy theorists suggest that someone—perhaps the U.S. government—destroyed the towers intentionally, possibly as a false flag operation to justify the subsequent War on Terror.

The film is still available for rent or purchase on Google Play, YouTube, and Apple TV at prices starting at $3.99 for standard rental. It is also listed on Amazon Prime Video though is currently unavailable to buy, with the most recent reviews there posted in late 2019.

A host of other conspiracy theory books and audiobooks are also for sale on Audible, Amazon, and iTunes, while countless free videos are available to view on YouTube.

An Amazon spokesperson told Newsweek: “We believe that providing access to written speech and a wide selection of physical media is important, including titles that some may find objectionable.

“We have policies that outline what products may be sold in our stores, which address content that is illegal or infringing. We remove products that do not adhere to our guidelines.”

The spokesperson said the details page for both Loose Change and 9/11:Ten Years of Deception—another conspiracy documentary—are still visible on the website due to customer entitlement.

This means if users have already purchased the content they can still own it in their online libraries. The two documentaries were made unavailable as they violated Amazon’s guidelines, though the spokesperson would not say which ones.

The Amazon-owned Audible service had been offering an audiobook of 9/11: Ten Years of Deception, but following Newsweek‘s queries the product page appeared to have been taken down.

A Google spokesperson told Newsweek that content will be removed from YouTube and Google Play if it is found to break the company’s policies and guidelines. As of the time of publication, the 9/11 conspiracy examples flagged by Newsweek had not been taken down.

Apple did not respond to Newsweek‘s requests for comment. At the time of publication, Loose Change was still available for purchase on Apple TV. However, the Apple Books product page for the 9/11: Ten Years of Deception audiobook appeared to have been removed.

James Leynse/Corbis via Getty Images

There is a bipartisan push to make tech giants more accountable for the content hosted on their sites. Section 230 legislation gives tech giants immunity for illegal content by making a distinction between a distributor and publisher of content online.

Social platforms are identified as the former and so do not have all of the same responsibilities as a publisher making editorial decisions.

Trump and his allies have repeatedly railed against Section 230, arguing platforms are publishers exercising editorial discretion and should be treated as such under the law.

Democratic senators are pushing the new SAFE TECH legislation, which would amend Section 230 and force platforms to take more responsibility for the content users upload.

Companies are still free to host questionable content and to charge users to access it or make money from advertising around it.

Still, their provision of 9/11 misinformation conflicts with public commitments to fight dangerous false information and conspiracy theories.

In October, YouTube released a statement noting it would ramp up efforts to remove dangerous conspiracy theory content from its platform, fearing its role in encouraging “real world violence.”

The video platform said these steps were taken to reinforce “four pillars,” which are commitments to remove violative content, reduce the spread of “harmful misinformation,” encourage authoritative voices, and reward “trusted creators.”

Amazon has recently removed books from sale promoting dangerous supposed “cures” for autism.

It also booted social media app Parler—popular with right-wingers and where misinformation and conspiracy theories were rife—off of its servers in the aftermath of the January 6 attack.

Google banned coronavirus misinformation adverts early in the COVID-19 pandemic, and—along with Apple—cracked down on apps spreading coronavirus conspiracy theories soon after the virus spread worldwide in 2020.

However, it appears the 9/11 attacks are not currently treated the same as the coronavirus pandemic, the 2020 election, QAnon, and other subjects ripe for misinformation.

Conspiracies about 9/11 are less politically relevant right now, and also less of an immediate threat to public safety.

But some of those with a personal connection to the tragedy said the tech companies are undermining efforts to educate Americans on exactly what happened on that pivotal day, and what it meant for the country and the world.

Both Ielpi and Van Hine work with the 9/11 Tribute Museum in New York City, which provides guided tours to visitors explaining what happened.

The organization has to date given more than 346,000 tours and hosted 4.1 million visitors at its museum on Greenwich Street, just blocks from where the Twin Towers once stood.

“Education is the key to make this world of ours better,” Ielpi told Newsweek from the west coast of Florida, where he now lives. “If we fail to educate our young people, we have failed miserably.”

But a lack of mandated 9/11 education in school curriculums and the pull of popular conspiracy theories online is making that work more difficult.

“I was actually surprised how many videos they were,” Van Hine said, noting that conspiracy theory content is mixed up with footage of real memorial services.

“I think it should be a different category.

“When you can watch a true documentary next to something that is promoting the conspiracy theory, that can get confusing.

“We have to make sure we’re educating children to question, but then to also believe there are things that are facts and truth.”

On the internet, “you’ve got a lot of information but you don’t have a teacher,” Van Hine added.

Ielpi said large media organizations and tech companies “have a responsibility to try and promote understanding,” regardless of their pervasive profit motives.

“They should be ashamed of themselves. Are they hiding under a rock? They’re going to say: ‘That’s not our responsibility.’ Well then, whose responsibility is it? It’s all our responsibility.”

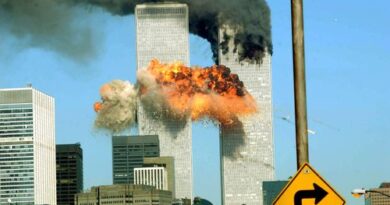

This is a global problem. Van Hine recalled a tour after which two young European men showed her photo of United Airlines Flight 175 about to hit 2 WTC and asked if she thought it was real.

“When something is inexplicable, so unbelievable, we believe that there has to be somewhat more than we’re being told,” she told Newsweek.

Ielpi said tech companies are flirting with Islamophobia and other hateful sentiments by failing to address conspiracy theory content on their platforms.

“These organizations will let these conspiracy people put their garbage out there for everybody to see, but yet still afraid to speak the truth about 9/11,” he told Newsweek.

Tech giants and media organizations, Ielpi said, have failed to seperate Islam the religion from the tiny number of “radical Islamic fundamentalists” that carried out and celebrate the attacks.

“Why are we continuing to be afraid to talk about radical Islamic fundamentalists?” he asked.

“We’re hiding in the shadows, afraid to speak the truth,” he told Newsweek.

“How long do we continue down this road, and how long do we allow these major organisations—Amazon and the rest—to promote hatred?”

“We’ve all failed. All of us have failed miserably.”

Ielpi continued: “Unless we promote this understanding about the Muslim religion, and how wonderful it is, the more we’re going to promote hatred by allowing these organizations to put this trash on the web.”

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Helen Lee Bouygues, a misinformation expert and founder of the Reboot Foundation, which looks to improve public critical thinking, said conspiracy theories thrive when people feel vulnerable and powerless, whether in the aftermath of 9/11 or in the midst of a pandemic. This is exacerbated by social media and the internet, she said.

Tech giants “deliberately have an algorithm to prey on people’s emotions so that your eyeballs stay on their social media platforms for longer.”

She added: “The other phenomenon that social media has enhanced further is this group that sense of belonging. It’s also a way for people to have a sense of being in a way of being an insider.”

Conspiracy theories have strong sticking power. People still argue about President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and the Moon landing.

Even Pizzagate—the 2016 theory that prominent Democrats were running a pedophile ring out of a Washington, D.C. pizzeria—has recently reemerged on TikTok.

Constant exposure can erode logic. “If people hear enough about misinformation and lies, they start believing it,” Bouygues said.

This is true of conspiracy theories, fake news, or propaganda campaigns by governments and special interest groups.

“The general population does not, is not willing to take the time or unable—in terms of their media literacy skills—to identify what content is coming from special interest groups.”

The 9/11 conspiracy theories drove a wave of online anti-government skepticism, particularly given the subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the latter justified with false intelligence and conducted despite United Nations opposition.

Such anger—whether legitimate or misplaced—can help drive new conspiracy theories.

Karen Douglas, a social psychologist at the University of Kent in the U.K. and an expert in conspiracy theories told Newsweek: “It is definitely the case that people who believe in one conspiracy theory tend to believe in others, even when the conspiracy theories are about completely different events, and even when they are about the same event but directly contradict each other.”

Some 23 percent of Americans believe that 9/11 was an “inside job,” according to data collated by Statista. Forty-five percent strongly disbelieve the assertion, though another 22 percent remain unsure.

But more people at least think something is amiss. A 2016 study by Chapman University found that more than half (54.3 percent) of those surveyed believed the government had concealed information about what happened on 9/11.

This is more than for the JFK assassination (49.6 percent) or the existence of aliens (42.6 percent).

Truthers have also gone on to be involved in other conspiracy theories, helped on that journey by Loose Change, which was perhaps the first viral blockbuster.

Last year, podcast host Moe Rock told Esquire: “Loose Change was the film that sent a lot of my peers down the rabbit hole. It was one of the fundamental catalysts for the online conspiracy theory boom. Probably the biggest one.”

Bouygues said political and business pressure will be the deciding factor as to whether tech giants act: “It’s purely political. The subject matter that is being raised, that is being addressed—it’s clear that the social media companies are watching what Washington D.C. cares about.”

Recent steps only came because President Joe Biden took the White House, she added: “They were worried that they were actually going to be liable for all of their content.”

Douglas said: “It’s not for me to say what content should be banned or limited, but some conspiracy content can be harmful and indeed, some of the social media companies are making efforts to reduce the availability of this content online.”

Van Hine and Ielpi, meanwhile, said they will continue to educate Americans about the tragedy as Washington, D.C. and Silicon Valley do battle over the future shape of the internet.

“If people are learning the history and learning some of the stories, they can use reason and logical thought hopefully if they see this conspiracy stuff,” Van Hine said.

“If you have no background information,” it’s more difficult, she added.

Van Hine fears that 9/11 conspiracies might grow in popularity as the event recedes further into history and personal connections with the tragedy are lost.

“Once it becomes history it almost becomes free game. I think maybe the generation that lived September 11 needs to just start telling stories.”

This year will be a painful one for the bereaved and survivors.

“Those directly affected will have to decide what you’re going to watch and not watch,” Van Hine said. “There is going to be a frenzy of stuff.”

Ielpi’s focus is the positive legacy of a horrendous event.

“We need to understand the good that has come from 9/11,” he told Newsweek, noting the many scholarship funds set up by bereaved families.

“People who lost loved ones on 9/11—they didn’t turn to hatred, they didn’t turn to conspiracy.

“My best friend, my son, was murdered on 9/11. Could I have turned my loss into hatred? You’re goddamn right I could. But you know what? Hatred loses in the long run.”

ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images