These locally elected officials posted or openly supported QAnon conspiracy theories

A normally orderly school board meeting in this small city began with an unusual warning that there should be no clapping or shouting. But things soon became so contentious that the meeting was brought to a halt for a 10-minute cooling-off period.

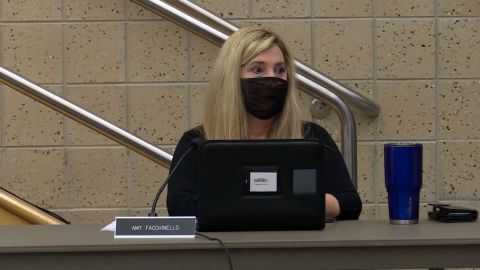

The tension had been building for weeks. Hours before the meeting, a group of students, retired teachers, and parents held a small demonstration at the high school, expressing their discontent with just one person: school board member Amy Facchinello.

Depending on who you ask, she’s either a QAnon sympathizer who poses a threat to the truth, and therefore to the education of the town’s children, or a hard-working woman being attacked for her partisan views.

Students and protestors opposing Facchinello are asking her to step down after then-high school senior Lucas Hartwell found social media posts alluding to QAnon on her Twitter account dating back to 2017, when the QAnon conspiracy theory first entered the American lexicon.

“It’s a platform that’s based on everything a school district should stand against, everything education should stand against,” said Hartwell. “And that’s the most upsetting part to me, that somebody who has the future of children believes these things that are so outlandish and so harmful to not just our community, not just our children, but to our nation and the world.”

Hartwell showed CNN copies of Twitter posts from Facchinello’s account, one saying, “Q ANON CONFIRMED BY TRUMP.” Another post about conservatives’ accounts being deleted with an image of a fiery “Q” says, “We the people are pissed off.”

There are a variety of retweets and likes of posts related to the QAnon movement, which is known for its outlandish conspiracy theories.

The debate in Grand Blanc is a window on tensions escalating in cities around the country where local elections have been won by people who appear to support, or in some instances openly support, QAnon and its associated conspiracy theories. The sides disagree on whether posts espousing support for QAnon will have any impact on people in the community who see them and what example they set for students, constituents and the democratic process itself.

Their elections have led to a divisive debate about whether it’s problematic to have these duly elected people in office if they share QAnon-related views. The debate has prompted questions about whether officials expressing such views is simply a free-speech right, a distraction from real government work, a bad example – or a real danger to the communities in which they serve.

Cancel culture or community danger?

Facchinello arrived at the high school where the May 24 board meeting as dueling protests were taking place outside.

Facchinello declined to sit down and discuss her views with CNN, but offered a brief explanation before walking into the meeting. She did not disavow QAnon specifically.

When asked by CNN’s Sara Sidner about her posts, she said she didn’t remember some of the ones Hartwell had found. Others, she said, were being used as part of a “false narrative.”

“I think it’s the false narrative to try to cancel Trump’s supporters,” says Facchinello, who was part of the Trump campaign in Grand Blanc.

Facchinello was one of 16 Republican electors in the 2020 presidential election who cast a symbolic vote for Trump on the periphery of the official vote, in which the state’s electors voted for Joe Biden, according to state law.

When CNN asked about a tweet on her account with the most common QAnon slogan “WWG1WGA,” Facchinello said the abbreviation, which stands for “Where we go one, we go all,” is “an inclusive message.”

Nobody but Facchinello knows what her intent was when she posted those messages. And that’s part of what has caused a problem in this city. She’s not currently openly embracing ideas or pushing for any QAnon-adjacent views to be taught in schools, but her leadership position in the town has created a battle over what should happen next. Facchinello has only just begun her six-year term on the board.

Hartwell believes other voters may not have known her views, or found out about them too late, like him.

Monica Shapiro, who raised four children in Grand Blanc, says she is ashamed and upset that someone who posted conspiracy theories like Facchinello could play a role in children’s learning.

“We have a person that believes in lies governing what should be taught in our schools,” she said. “And that just isn’t right. We have to have facts. We have to have reality.”

Some Facchinello supporters brought their signs from the protest inside the board meeting itself. One reads: “Conservatives, still the majority.”

Cara McAlister came from Bloomfield Township to support Facchinello. She was holding a sign of her own at the protest declaring, “Conservatives won’t be cancelled.”

Michael Smith, from nearby Sanilac County, believes Facchinello is being unfairly cast as a villain. “She’s wonderful, loving, caring, loves the kids. And just because they have a different perspective, they’ve made her into a villain,” he said.

He believes diversity of viewpoints on the school board is a good thing.

“It’s about free speech. This is about her right to feel what she believes. And she’s not trying to indoctrinate anybody or bring that in or anything,” said Smith. “She loves kids. She loves people. She loves her job. She’s a good teacher.”

The sides disagree on whether those posts will have any impact on people in the community who see them and what example they set for students.

In fact, several students at the protest who back Facchinello and are lacrosse teammates with her son, said not only have the protests gone too far, but they agree with some QAnon views.

High school junior A.J. Smith is one of them.

“I think personally, QAnon, parts of it are real. I mean, people say it’s just conspiracy, but some of it’s pretty real. Some of it’s ridiculous, obviously,” he said. Smith goes on to explain how “shady things” are happening in Washington, DC, and Hollywood.

Either way, it boils down to one basic thing, Smith said: “If she posted something about it that’s her right.”

‘We’re at the beginning of this, not the end’

Facchinello isn’t the only candidate linked with views connected to QAnon to attract local attention and cause some dissension in the communities where they were elected.

Liberal media watchdog group Media Matters tracks QAnon’s political clout and found 19 congressional candidates, 18 of whom are Republicans, who it says have shown support for QAnon conspiracy theories and have announced they are running in the 2022 election cycle.

“We’re at the beginning of this, not the end,” Media Matters president and CEO Angelo Carusone said. “There’s a flash point right now. They’re on the ascent.”

Carusone said the violent Capitol breach on January 6 didn’t kill the movement, but in many ways emboldened it.

“The real threat of all of this isn’t so much you know that it’s some wacky ideas,” Carusone says. “The ideas are actually a rationalization for harming basically everybody that QAnon brands as an enemy.”

Some elected officials are openly embracing the conspiracy theories – and, Media Matters argues, gaining support by doing so – even as it causes some havoc in the areas they are supposed to represent.

Former UFC Champion Tito Ortiz was elected as a member of the city council and mayor pro tem of Huntington Beach, California, in November.

Ortiz came under fire due to controversial anti-masking comments during the pandemic. He refused to wear a mask when asked to do so to attend in-person city council meetings when they resumed this year, prompting members to continue to meet online for months.

Ortiz continually posted content on social media related to QAnon, wore the Qanon linked acronym WWG1WGA shirt, and shared unfounded conspiracy theories about George Floyd’s death, and the pandemic.

Ortiz, like Facchinello in Michigan, has also had some posts flagged as misinformation on social media.

Some of his fellow council members, including both Democrats and Republicans, believe his views became a distraction and have resulted in less time being spent dealing with policy and council business and more time sharing memes and misinformation.

“Well, the first day when he was sworn in, he referred to the pandemic as a ‘Plandemic’ and that sort of set the tone, said Mike Posey, a Republican.

The “Plandemic” is a reference to a debunked conspiracy theory that the government, climate scientists, the US Centers for Disease Control, Big Pharma and others planned the pandemic for nefarious reasons. Ortiz pushed the idea as California was suffering from an onslaught of Covid-19 deaths and packed hospitals.

After five months, Ortiz’s tenure on the city council abruptly came to an end on Tuesday night during the council’s first in-person meeting of the year when he resigned, saying his decision was in part due to hostility among the council, and “character assassination each and every week.”

He also said he was resigning to protect his family.

“I tried as hard as I possibly could, but when my children’s safety becomes a matter, I’m a father and I’m going to protect my children,” Ortiz said.

Ortiz’s children were thrust into controversy by he and his girlfriend. His girlfriend filmed as she sent the children to school without wearing masks, though they were required. She posted the video publicly with the children’s faces fully visible to her thousands of followers.

Ortiz had repeatedly posted on social media that children shouldn’t be required to wear masks, claiming it endangered their health.

Ortiz’s children were sent home from school for not wearing masks, according to an Instagram video in which his girlfriend expresses anger at the situation.

Ortiz declined CNN requests for an interview and did not comment to CNN at the council meeting on Tuesday about his views or resignation.

A push for higher office

In Arizona, Republican state Rep. Mark Finchem has repeated conspiracy theories on fringe conservative media and at least one high-profile podcast known for being supportive of QAnon.

“We’ve got a serious problem in this nation,” he said in a separate interview on Victory Media. “There’s a lot of people involved in a pedophile network in the distribution of children … And, unfortunately, there’s a whole lot of elected officials that are involved in that.” Finchem was first elected to his position in 2014 and re-elected last year.

Comments like that have led to efforts to recall Finchem. Calden Rasmussen is a young Republican and one of dozens of volunteers leading a recall effort in Finchem’s district, near Tucson, Arizona.

“We have a ton of people who need help, need laws passed,” Rasmussen said. “He’s out there focusing on conspiracy theories, which is honestly just disgusting.”

Finchem shared some of his beliefs when he went on a QAnon podcast on May 9, detailing his view that we are witnessing a slow-motion coup and that Trump won the election. He has spoken about “the deep state” and reposts multiple accounts supportive of QAnon conspiracies on social media platform Gab.

Finchem declined to comment and did not return calls or e-mails from CNN with questions about his views.

Finchem was an ardent supporter of the Stop the Steal campaign and posted what appears to be support for “The Big Lie,” from outside the Capitol on January 6.

He is currently campaigning again, this time for a higher role in local government. If he wins his campaign to become Arizona’s secretary of state, he will be the state’s top election official.

Finchem has also been a supporter of the repeated election ballot audits in Arizona. He was considered one of the foremost pushers of the Stop the Steal movement in the state.

That’s a real concern for Natali Fierros Bock, who is the organizer of the effort to recall Finchem. “Somebody like Rep. Mark Finchem being in charge of elections, holding a seat like secretary of state is one of the most dangerous things that could happen to democracy,” she said.