Not Every QAnon Believer’s an Antisemite. But There’s a Lot of Overlap Between Its Adherents and Belief in a Century-Old Antisemitic Hoax

The Capitol riots were rife with symbols of humanity’s hate-filled past, but perhaps one of the most startling and enduring images was that of a man in a sweatshirt that said “Camp Auschwitz: Work Brings Freedom” — a reference to the eponymous Nazi extermination camp and its infamous motto, “Arbeit Macht Frei.”

A new Morning Consult survey tracking right-wing authoritarian beliefs shows that while not all believers of the conspiracy theory that helped spur the insurrection are antisemites, a large majority of adherents to a century-old antisemitic hoax are also believers of QAnon. And though efforts to deplatform the conspiracy group have sent QAnon underground, data shows that believers’ views on the issues that led to the insurrection track closely with those of self-identified U.S. conservatives.

U.S. adults in the April 26-27 survey were asked questions regarding two notable conspiracy theories: QAnon — described as a belief that the world is run by a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles made up of left-wing politicians, religious figures and Hollywood elites — and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a hoax document first published in the early 1900s that alleges a Jewish plot to take over major institutions in an effort at world domination.

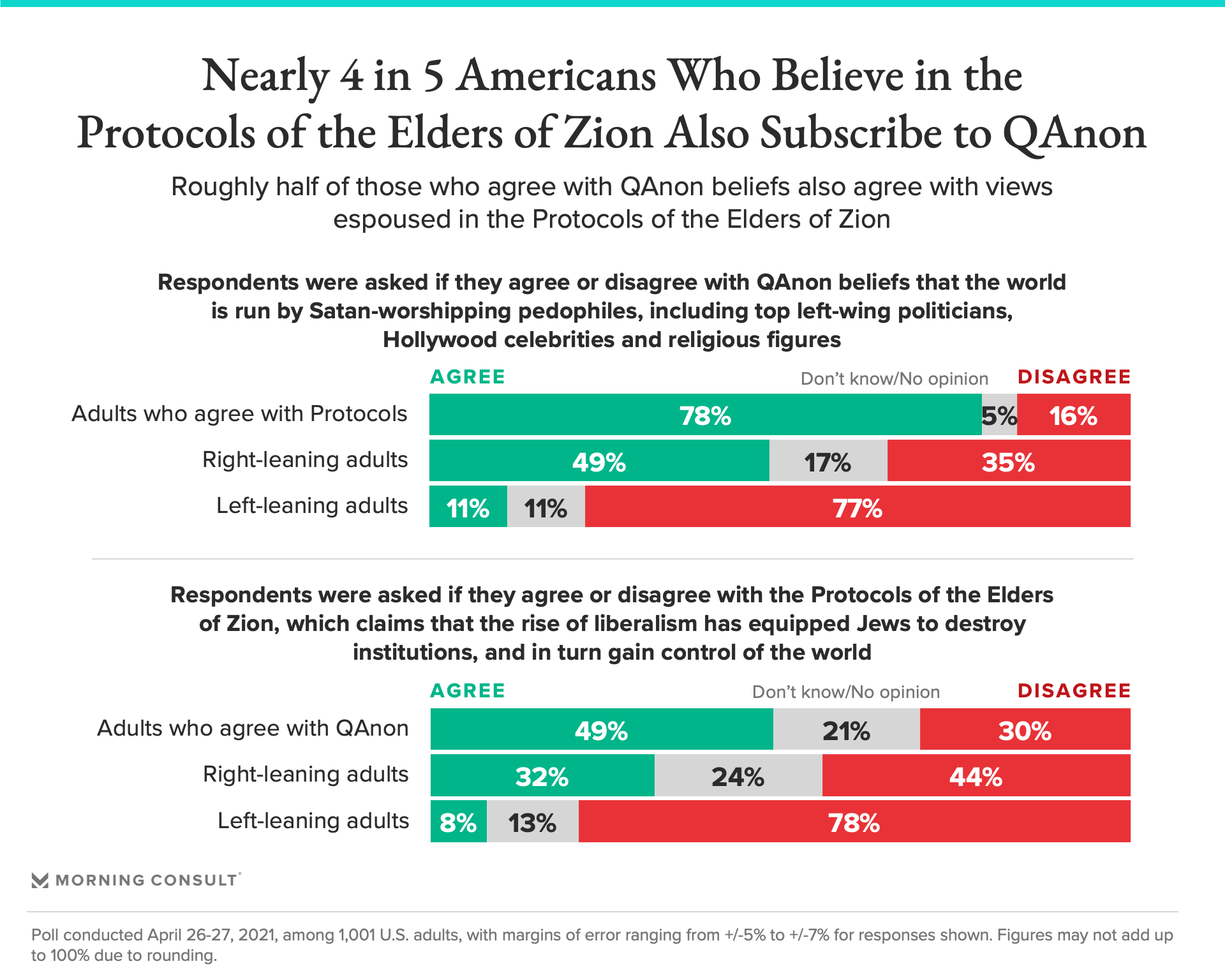

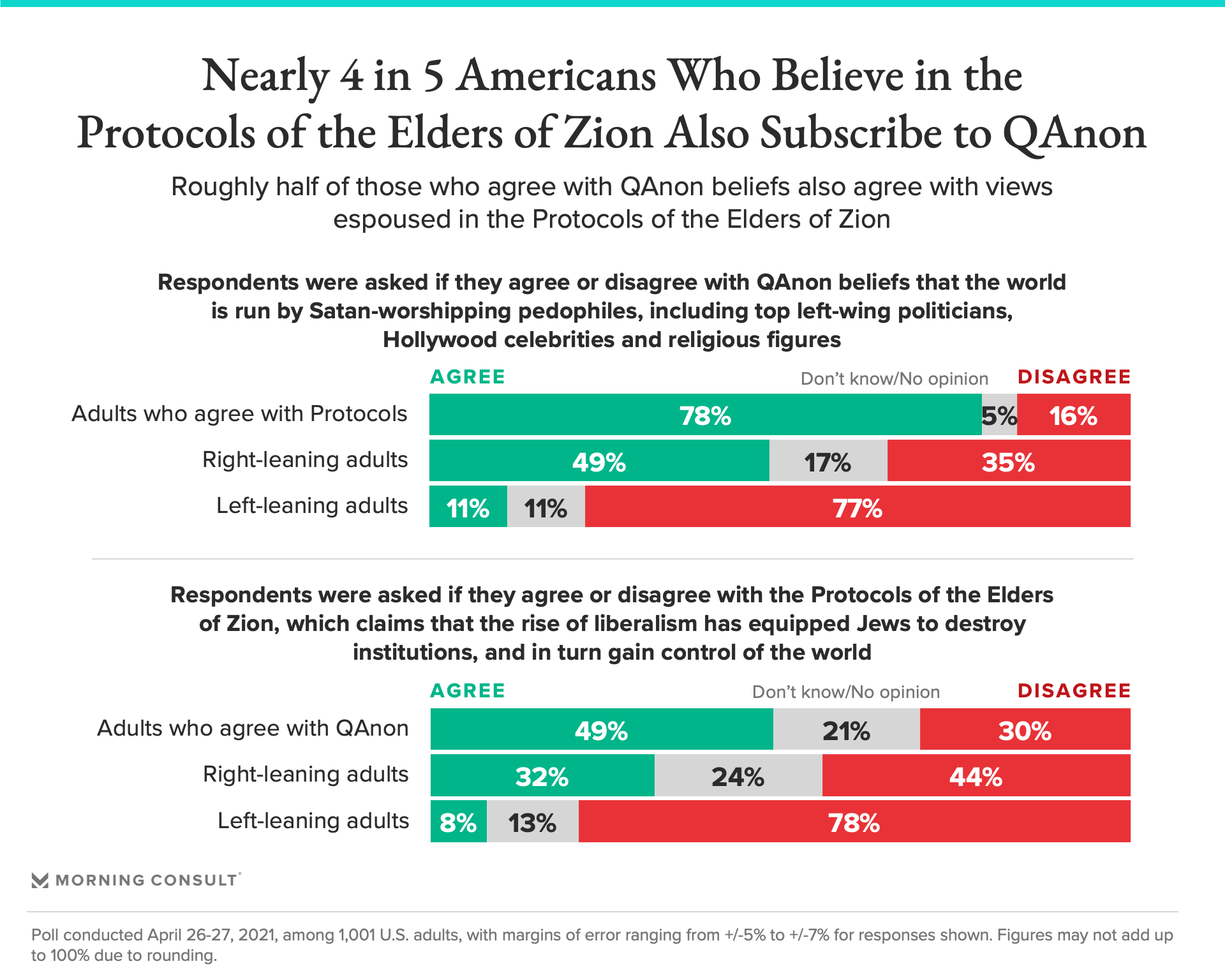

Seventy-eight percent of U.S. respondents who agreed with the Protocols of the Elders of Zion also agreed with QAnon, while 49 percent of QAnon adherents agreed with the century-old antisemitic slur, compared to 32 percent of right-leaning adults and just 11 percent of left-leaning adults.

“Although we wouldn’t say initially that QAnon had antisemitic tropes, very quickly it became apparent that there was a strain within QAnon belief that articulated some of these very clearly antisemitic tropes,” said Joanna Mendelson, associate director of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism. More specifically, QAnon adherents “identify Jewish control of the media, the banks and the government as being behind the Deep State, helping to manipulate the levers of society and undermine trust.”

The group has undergone a sea change in recent months: Both Twitter Inc. and Facebook Inc. started cracking down on QAnon communities and content as early as last summer, and sought to strengthen their moderation efforts following the insurrection, effectively deplatforming the conspiracy group.

A spokesman for Twitter said the company has been clear that it will take strong action on behavior that has the potential to lead to offline harm, and since Jan. 8 has suspended more than 150,000 accounts that “were engaged in sharing harmful QAnon-associated content at scale and were primarily dedicated to the propagation of this conspiracy theory across the service.”

Following the failure of the “Stop the Steal” rallies and Capitol insurrection to prevent Biden’s presidency, the QAnon movement has been retooling and reorganizing.

“Q hasn’t posted since December,” said Aoife Gallagher, an analyst with the Institute for Strategic Dialogue’s Digital Analysis Unit, referring to the conspiracy theory’s eponymous leader who spurred the movement with his “Q drops.” “Really what a lot of the community is doing is that they’re latching on to different influencers that have built up audiences over the last few years.” And many of those influencers are now flourishing on less-moderated spaces such as Telegram, which Mendelson described as “lion’s dens for extremist ideology.”

Take GhostEzra, for instance, “essentially a marginal figure when it came to QAnon while on Twitter, who had roughly 18,000 followers prior to the mass ban, but who now has essentially amassed 338,000 subscribers,” said Mendelson.

The QAnon influencer, who was described by Vice News last month as the subject of a war within the community due to his openly antisemitic posts and Holocaust denialism, “in a very short space of time pivoted to very, very blatant antisemitism — borderline neo-Nazism,” Gallagher said.

“When you remove QAnon communities from Facebook and the like, like that, you’re pushing them into more extremist spaces,” she added. “Now, I do think that it stops them building their audience in the same way that they were able to use the algorithms of Facebook and YouTube to build their audience over the last number of years.”

Telegram did not respond to a request for comment.

But that doesn’t mean QAnon has disappeared. Instead, ideas that originated in the QAnon space — such as allegations of widespread voter fraud — are now filtering into mainstream right-wing ideology, without the name attached.

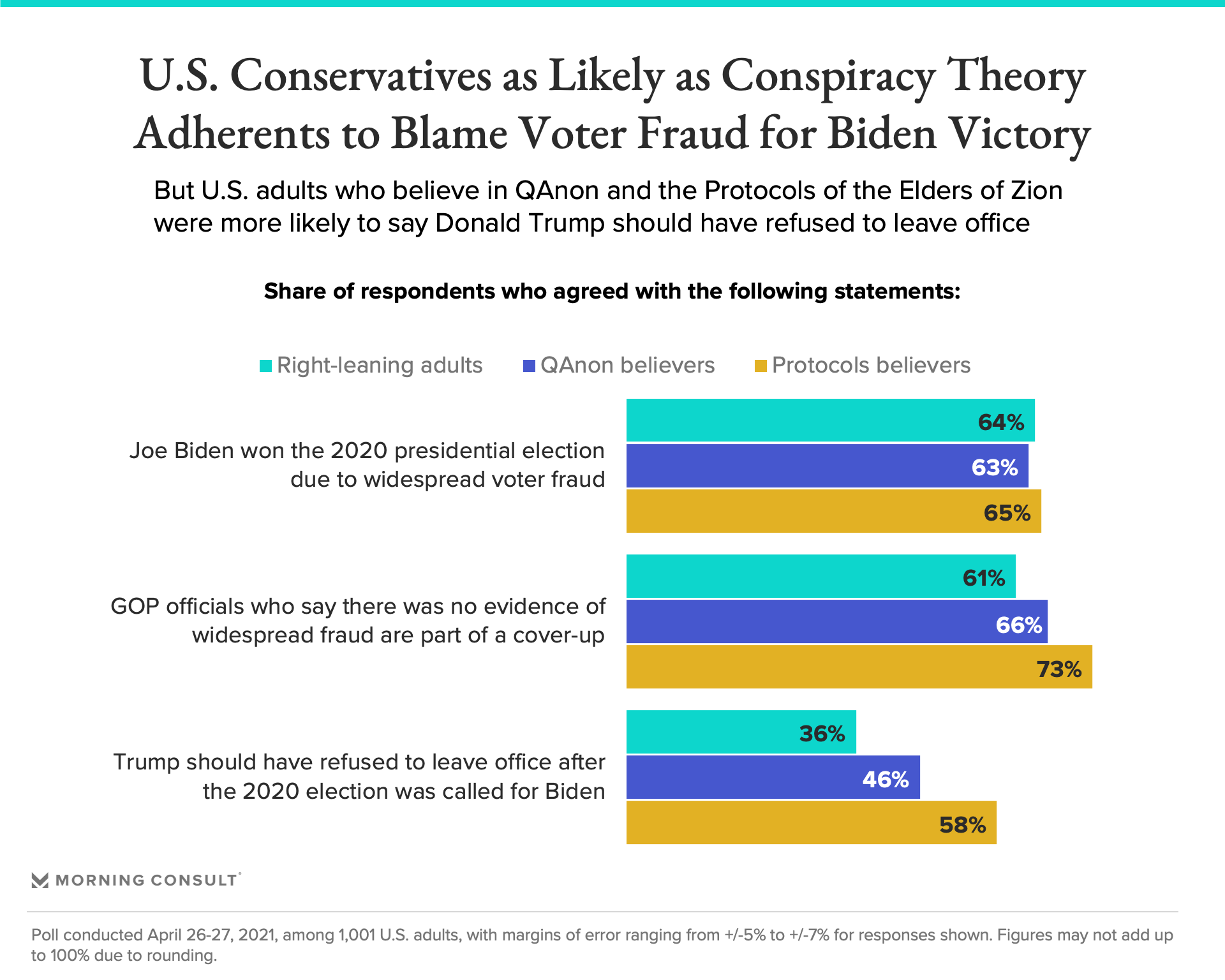

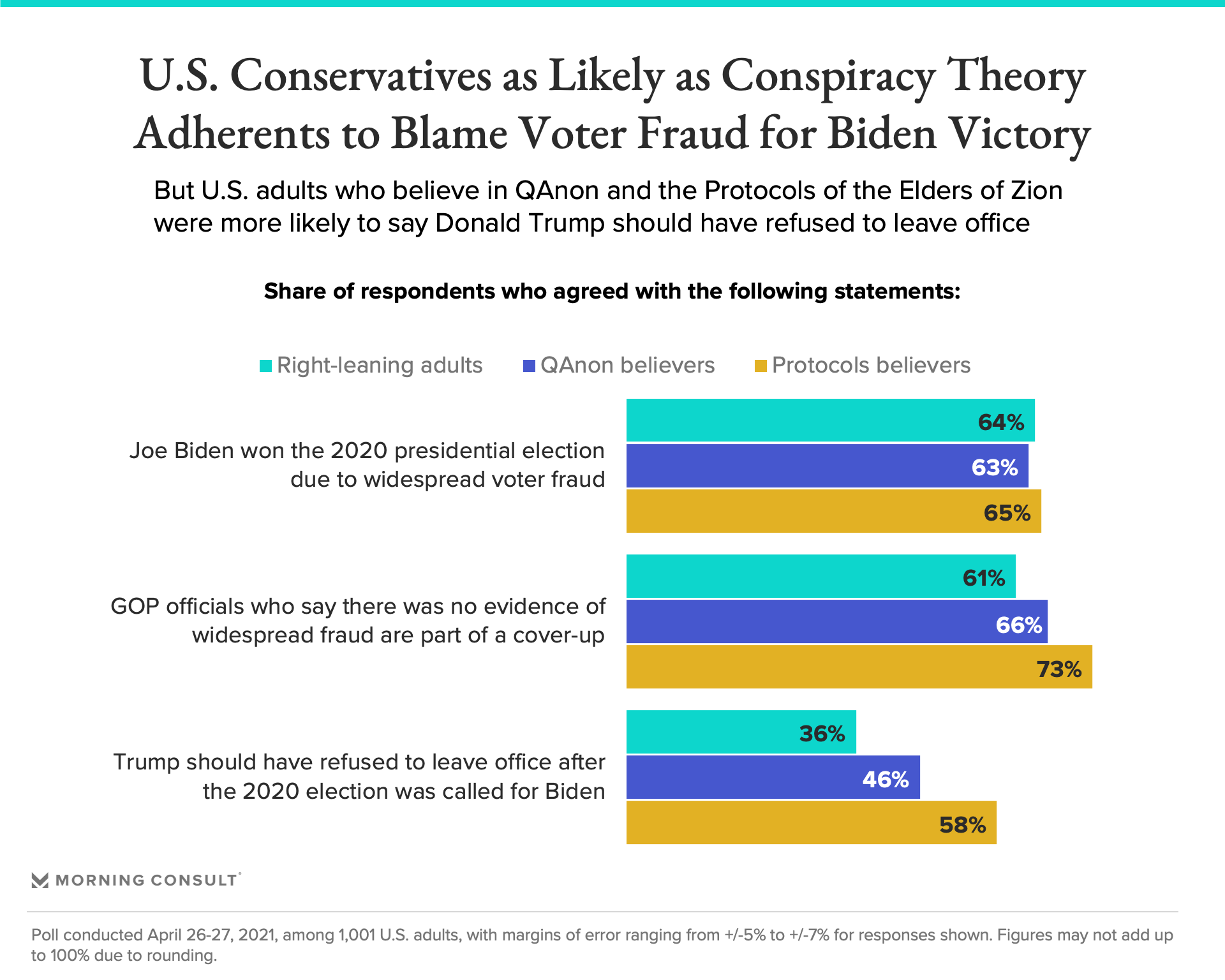

In the survey, more than 3 in 5 right-leaning adults said they agreed that Joe Biden won the election due to widespread voter fraud, roughly on par with the share of QAnon and Protocols believers who said the same.

“You can’t overstate, really, how much QAnon had a role in what happened on Jan. 6,” Gallagher said. “QAnon had been pushing voter fraud claims well before last year.”

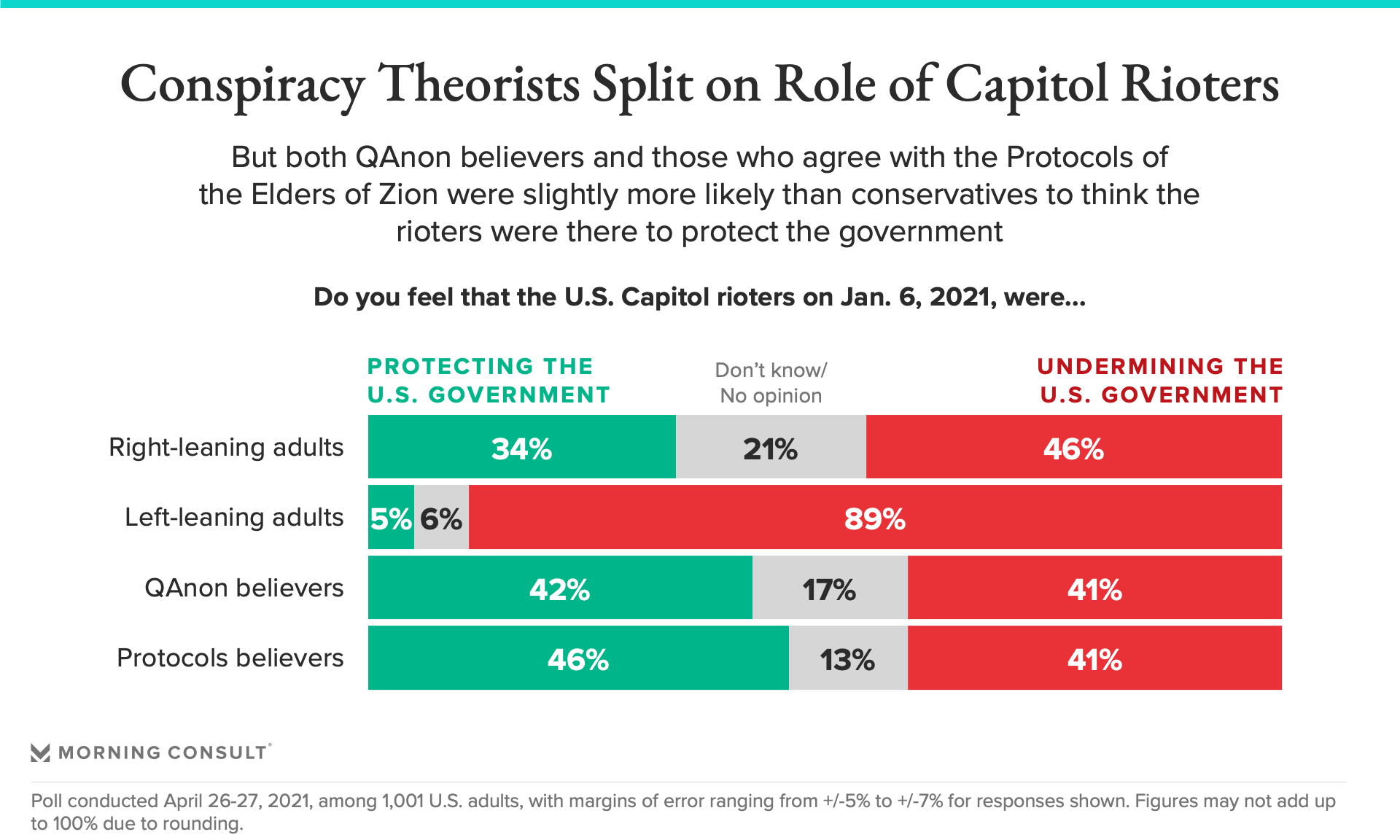

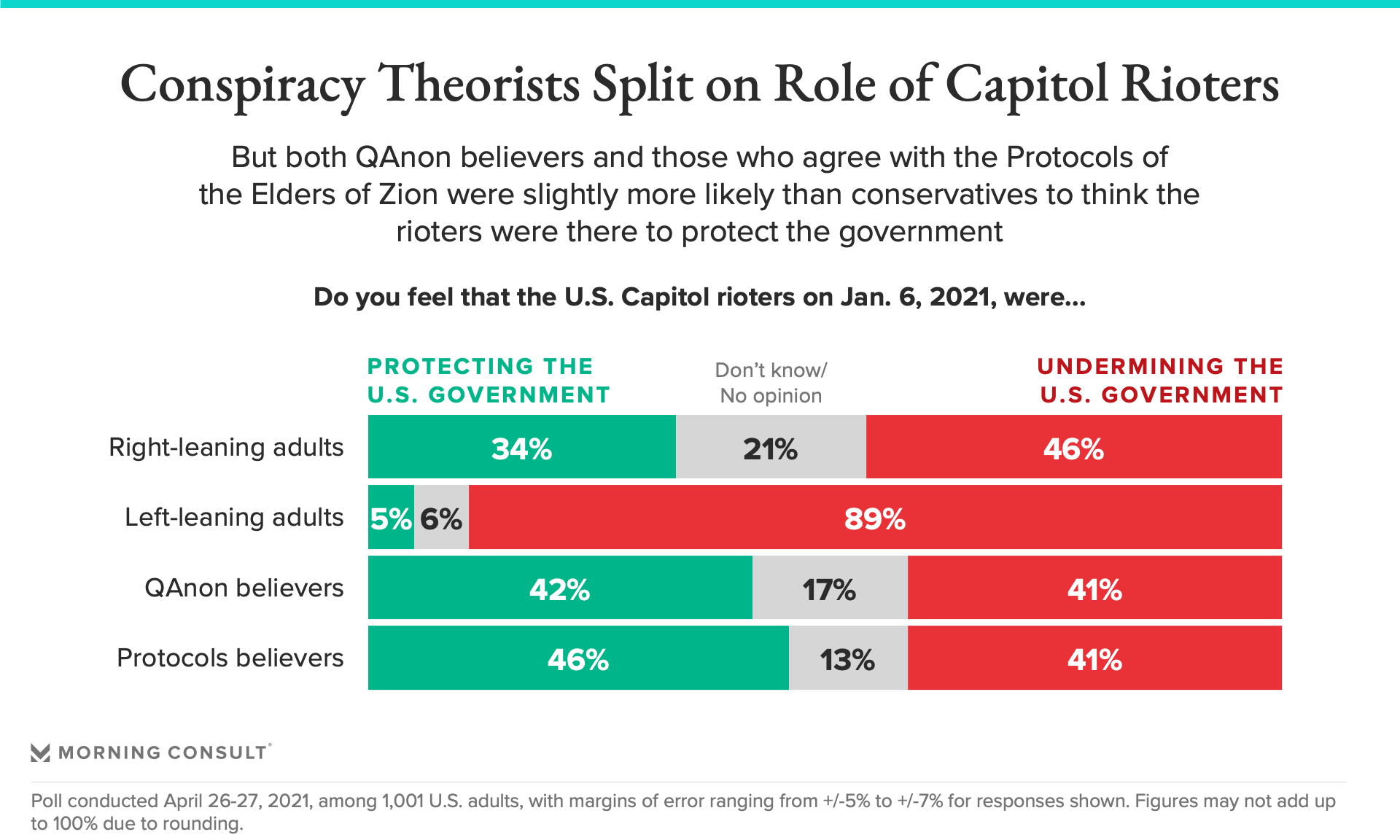

When it came to the Capitol riots, QAnon believers and those who agree with the Protocols of the Elders of Zion were basically split on whether the insurrectionists were there to protect or undermine the government, though both groups were slightly more likely than right-leaning adults to say it was the former.

While the Capitol rioters did not succeed in overturning the election, QAnon circles are still focused on the fight.

“We’re seeing them talk about themes that either ask for auditing of the election or that make claims that Trump will be reinstated or identify or promote a similar belief,” Mendelson said. A Morning Consult survey conducted earlier this month found that 29 percent of GOP voters thought it likely the former president would return to office sometime this year. And a different survey showed that just over half of Republicans thought election reviews could change the outcome of the 2020 contest.

“I think the influence of QAnon in the wider Republican Party is huge,” Gallagher said. “But people wouldn’t recognize that it’s QAnon.”

Experts say QAnon beliefs have also filtered into the halls of Congress, with both Mendelson and Gallagher citing freshman Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) as an example of the group’s mainstream influence.

“She’s kind of nearly put herself in there as one of the de facto leaders of that movement now,” Gallagher said, “even though she’s disavowed it, but she still plays into their narratives all the time.”

Greene has come under fire over the past few months for her controversial statements, including a 2018 Facebook post blaming the Rothschilds — a Jewish banking family that has been the subject of many antisemitic conspiracy theories — for California wildfires and a tweet comparing vaccination identification to the gold stars Nazis forced Jewish people to wear during the Holocaust. (She has since apologized for the equivalence.)

Earlier this month, she also tweeted a conspiracy theory that the “Deep State” and Federal Bureau of Investigation operatives were “involved in organizing and carrying out the Jan 6th Capitol riot.”

Greene said in a statement emailed to Morning Consult that “I have never once promoted Q Anon as a candidate or a member of Congress, but do you know who has promoted it nonstop: the media, just like you are doing with this article. Nancy Pelosi and CNN believe in Q Anon far more than I ever did.”

Per a tweet from Daily Beast reporter Will Sommer earlier this year, Greene in December posted on Twitter praising an article by Gab Chief Executive Andrew Torba in which he promotes QAnon and calls the conspiracy group “a refreshing and objective flow of information.”

“In this current landscape, we are seeing mainstream figures, thought leaders and politicians push extremist narratives in the public sphere,” Mendelson said. “And increasingly, the line is becoming very blurred between these fringe beliefs and some of these more conservative ideals.”

Data indicates that not only are the lines becoming blurred, but that fringe belief groups and the U.S. right wing are largely on the same page when it comes to authoritarian tendencies. As part of its survey, Morning Consult polled adults in eight countries and ranked their responses based on a right-wing authoritarianism scale originally created by longtime authoritarian researcher Bob Altemeyer.

The findings show that not only does the United States’ right flank have the highest mean ranking among that group in all countries (109.3, 10 points higher than the next-highest ranking), but so do its QAnon believers, with both groups ranking above 100 on the scale, which starts at 20 and ends at 180. Canada’s adherents of the Protocols of Elders of Zion actually had a slightly higher mean score than their American counterparts, but both groups were above 100 and within a third of a point of each other.

Any solution to the proliferation of QAnon, both experts said, must involve the tech industry.

The Internet Association, a stakeholder group representing major internet companies such as Facebook, Google and Twitter, said in an emailed statement that “internet companies have taken and continue to take thoughtful actions to address the abuse of their services by extremist groups, including by banning accounts and removing threatening or harmful content. Policies and enforcement techniques are regularly reevaluated and updated to keep pace with changes in extremist behavior, and our industry welcomes opportunities to collaborate with other stakeholders to improve the safety of their services.”

And Twitter said it is looking into ways to empower research into QAnon and other coordinated harmful activity on the platform, as well as focusing a significant part of its enforcement efforts on accounts engaged in ban evasion, though the company acknowledged that it has to work hard to stay ahead of bad actors in the online space.

“Obviously, there’s no magic wand, there’s no silver bullet for how to solve this,” Gallagher said. “But I do think that providing people with the tools that they need to be able to find accurate information or to be able to recognize the fact that certain types of information is not reliable — I think that that will go a big way, hopefully, to kind of figuring out how to get through this.”

Mendelson also suggested a “multipronged solution” involving not only the tech industry but law enforcement, the legislature, education and community groups.

In the meantime, she warned, the grievances that were expressed on Jan. 6 are still brewing — and could lead to more violence.

The retooling of QAnon in the wake of the insurrection “is combined with a sort of desperation, and that desperation is very dangerous,” she said. “When one doesn’t feel like the democratic process is working properly, when one feels their voice has been silenced, when one feels that their vote does not count — that can pave the way for potentially radical action.”