Vaccination‐hesitancy and vaccination‐inequality as challenges in Pakistan’s COVID‐19 response

1 INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak started in Wuhan city in China in mid-December 2019. The first case of COVID-19 in Pakistan was reported in Karachi on February 26, 2020. The patient-zero in Pakistan had traveled from Iran (Saqlain et al., 2020; Yousaf et al., 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it as public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020 (Saqlain et al., 2020), but due to its rapid spread throughout the world and severity of illness, the WHO named it as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 (Abid et al., 2020). A variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, characterized as VOC-202012/01, emerged in the UK on December 14, 2020, which by January 27, 2021, had quickly spread to over 64 countries (Umair et al., 2021). The WHO estimates that different vaccine programs, in general, across the world prevent 2–3 million deaths every year (Robertson et al., 2021). If vaccine coverage is increased with effectiveness, it can save a further 3.5–4.5 million deaths globally. The 34 billion USD investment on the expansion of global outreach for vaccinations could save 586 billion USD against direct costs of illness, which could benefit further 1.5 trillion USD in larger economic benefits (Khattak et al., 2021). RAND Corporation estimates a USD 3.4 trillion annual worldwide economic impact of COVID-19 and a USD 1.2 trillion annual loss to the global economy due to unequal distribution of COVID-19 vaccine (Hafner & Stolk, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused multiple socioeconomic problems in Pakistan due to the country’s fragile politics, struggling economy, and unstable healthcare system (Haqqi et al., 2021). Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated that Pakistan’s economy has lost around USD 4.95 billion due to COVID-19 pandemic and triggered 946,000 job losses (Ilyas et al., 2020). Furthermore, the COVID-19 related lockdowns could cause the layoff of 12.3 to 18.53 million Pakistanis, which will destroy the country’s already struggling economy (Yousaf et al., 2020). However, according to Haqqi et al. (2021), lack of capacity and resources for testing COVID-19 and inequitable vaccination may put the country at an even greater risk than the socioeconomic impacts of this pandemic. Haqqi et al. (2021) observations support the speculations that the actual number of cases is way higher than what is reported. Initially, Pakistanis believed that their stronger immune system and hot weather in the country would prevent them from severe impacts of COVID-19 as compared with other countries like Italy, Iran, and United States. But the fear in Pakistan was sparked by the strict measures for the funerals of those who died of COVID-19 infections whose funerals happened without physical contacts and gatherings. (Shoukat & Jafar, 2020).

There has been intense global competition among vaccine developers followed by a similar trend in nations racing to get vaccinated first. However, despite WHO’s warnings, less attention and debate have gone into making vaccines available to developing countries. Another question that has not been given enough attention is how the COVID-19 vaccine would be distributed equitably among communities once made available to developing countries. Therefore, there is an urgent need for further research on equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccine globally between the core and peripheral countries but also within the peripheries, which are usually marked by power differentials and corrupt political systems.

In this backdrop, our study looks at the issue of the equitable delivery of the COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan and people’s response to the COVID-19 vaccination. In particular, the study explores what socio-cultural, religious, and economic factors support and/or impede equitable access to COVID-19 vaccination. We use a literature synthesis approach to highlight the accessibility issues and people’s response towards the COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan. The article is organized in three sections, namely, synthesis of the literature on COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan, thematic content analysis, and discussion on tackling the issues of hesitancy and equality towards COVID-19 vaccination. These are then followed by conclusions and recommendations for future research.

2 COVID-19 VACCINATION WORLDWIDE: AN OVERVIEW

The first human clinical trial of a COVID-19 vaccine commenced on March 03, 2020, in the United States (Murphy et al., 2021). As of May 2, 2021, 60 vaccines were at the different phases of their trial, and 13 vaccines (Table 1) had already been authorized to vaccinate people in different countries (Craven, 2021). Among major manufacturers, Pfizer planned to make two billion COVID-19 vaccine doses in 2021, AstraZeneca three billion, and Moderna one billion (Baraniuk, 2021). These counts are in addition to the other authorized vaccines manufactured in China, India, and Russia. Among authorized ones, five were available in Pakistan as of May 2, 2021.

| No | Name | Vaccine type | Primary developer | Country of origin | Authorized in Pakistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Comirnaty (BNT162b2) | mRNA-based vaccine | Pfizer, BioNTech; Fosun Pharma | Multinational | No |

| 2 | Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine (mRNA-1273) | mRNA-based vaccine | Moderna, BARDA, NIAID | US | No |

| 3 | COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca (AZD1222); also known as Vaxzevria and Covishield | Adenovirus vaccine | BARDA, OWS | UK | Yes |

| 4 | Sputnik V | Recombinant adenovirus vaccine (rAd26 and rAd5) | Gamaleya Research Institute, Acellena Contract Drug Research, and Development | Russia | Yes |

| 5 | COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen (JNJ-78436735; Ad26.COV2.S) | Non-replicating viral vector | Janssen Vaccines (Johnson & Johnson) | The Netherlands, US | No |

| 6 | CoronaVac | Inactivated vaccine (formalin with alum adjuvant) | Sinovac | China | Yes |

| 7 | BBIBP-CorV | Inactivated vaccine | Beijing Institute of Biological Products; China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm) | China | Yes |

| 8 | EpiVacCorona | Peptide vaccine | Federal Budgetary Research Institution State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology | Russia | No |

| 9 | Convidicea (Ad5-nCoV) | Recombinant vaccine (adenovirus type 5 vector) | CanSino Biologics | China | Yes |

| 10 | Covaxin (BBV152) | Inactivated vaccine | Bharat Biotech, ICMR | India | No |

| 11 | WIBP-CorV | Inactivated vaccine | Wuhan Institute of Biological Products; China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm) | China | No |

| 12 | CoviVac | Inactivated vaccine | Chumakov Federal Scientific Center for Research and Development of Immune and Biological Products | Russia | No |

| 13 | ZF2001 | Recombinant vaccine | Anhui Zhifei Longcom Biopharmaceutical, Institute of Microbiology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences | China, Uzbekistan | No |

- Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

- Source: (Craven, 2021).

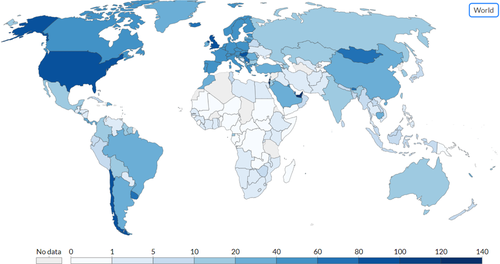

Figure 1 (below) depicts COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people worldwide. Even though there is considerable scientific evidence that vaccines reduce mortality and morbidity rates, there is a significant number of Anti-vaxxers and vaccine “hesitants” in every country (Dubé et al., 2013). Anti-vaxxers are those individuals or groups of individuals who oppose the vaccinations, and vaccine-hesitants are those who “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccine service” (Boodoosingh et al., 2020; MacDonald & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy, 2015). Thus, the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance is not the same among people living in different countries, as vaccine hesitancy is a global phenomenon (Biddle et al., 2021; Macpherson, 2020). The people who hesitate to be vaccinated are often more than those who just resist the roll-out of vaccination programs. For example, 31% of the surveyed population in the United States were hesitant to have the COVID-19 vaccine, 25%–27% in the UK, 14% in Canada, 9% in Australia, and an average of 19% were hesitant in seven European countries (Dube et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2021). Though vaccines are the most efficient method of preventing and controlling the pandemics like COVID-19 (Wong et al., 2020), vaccine hesitancy is a global phenomenon derived from various factors, not merely linked to religion (Seifman & Forthomme, 2020). For instance, in the United States, millions of white evangelical adults do not want to be vaccinated against COVID-19 due to various reasons, including a belief that the COVID-19 vaccine contains the tissues of aborted cells (Pew Research Center, 2021).

3 COVID-19 VACCINATION IN PAKISTAN

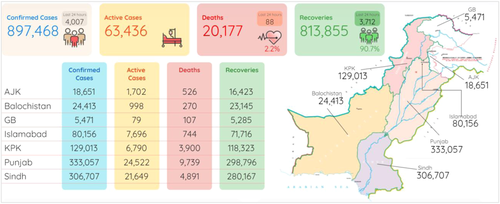

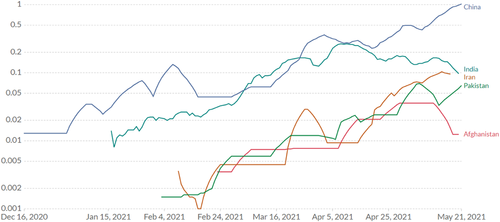

As of May 2, 2021, the WHO (https://COVID19.who.int/) reported that the world has 150,989,419 confirmed cases of COVID-19, and 3,173,576 deaths. Figure 2 presents the official statistics of the COVID-19 situation in Pakistan. Figure 3 depicts COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people in and around Pakistan. Pakistan’s geographic location was critical due to its border with China, the country of COVID-19 origin, and Iran, the first Islamic epicenter of COVID-19 among the Muslim countries (Yousaf et al., 2020). The major sources of the COVID-19 outbreak in Pakistan were the unscreened return of over 7000 pilgrims from Iran and the careless week-long religious gathering of 1,250,000 followers of the Tablighi Jama’at (an Islamic proselytizing group) in Lahore (Farooq et al., 2020). Furthermore, the religious leaders continuously defied the implementation of socially distanced religious activities in mosques and shrines. The government could implement the lockdown for most businesses and schools, except mosques where religious gatherings take place multiple times a day (Shoukat & Jafar, 2020). These social and religious attitudes towards the pandemic led to a rapid increase in COVID-19 infection rates in Pakistan. As of May 22, 2021, there were 20,177 deaths against 897,468 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Pakistan (see Figure 2).

On the other hand, once the vaccines became available in Pakistan these very attitudes and practices can be seen behind the rising vaccination hesitancy in the country. The COVID-19 knowledge, attitude, and practice study by the Center for Communication Program at John Hopkins University found the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Pakistan was 67%. Whereas the Vaccine Confidence Project found the growth of anti-vaccine sentiments in Pakistan from 2% to 4% due to instability and anti-vaccine religious leadership (MacPherson, 2020). In this backdrop, it becomes important to examine what sociocultural, religious, and economic factors support and/or impede equitable access to COVID-19 vaccination.

4 METHODOLOGY

A systematic literature synthesis was undertaken to examine the COVID-19 vaccination situation in Pakistan. The synthesis of the systematic review was based on two approaches. The first approach was to check the Web of Science database from 2020 to May 2021 using four indexes, that is, Science Citation Index Expanded, Arts and Humanities Citation Index, Emerging Sources Citation Index, and Social Sciences Citation Index. The research on COVID-19 vaccination is emergent, and the concept of COVID-19 is still evolving in Pakistan. In total, we identified 27 articles from the research database, namely Web of Science, Scopus, EBSCO, and others from related disciplines (see Table 2). The second approach was to analyze policy reports, news briefs, and public announcements by Pakistani officials on COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan. We decided to use this approach as it had a greater level of significance of the COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan. This approach helps us analyze and review the public and institutional responses to COVID-19 Vaccination in Pakistan. We present the summary of key findings along with the remedial actions in the subsequent sections.

| No | Authors | Title | Year published |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mehmood, K; Bao, YS; Petropoulos, GP; Abbas, R; Abrar, MM; Saifullah; Mustafa, A; Soban, A; Saud, S; Ahmad, M; Hussain, I; Fahad, S | Investigating connections between COVID-19 pandemic, air pollution, and community interventions for Pakistan employing geoinformation technologies | 2021 |

| 2 | Khan, MT; Ali, S; Khan, AS; Muhammad, N; Khalil, F; Ishfaq, M; Irfan, M; Al-Sehemi, AG; Muhammad, S; Malik, A; Khan, TA; Wei, DQ | SARS-CoV-2 genome from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan | 2021 |

| 3 | Singh, J; Malik, D; Raina, A | Immuno-informatics approach for B-cell and T-cell epitope-based peptide vaccine design against novel COVID-19 virus | 2021 |

| 4 | Oud, MAA; Ali, A; Alrabaiah, H; Ullah, S; Khan, MA; Islam, S | A fractional order mathematical model for COVID-19 dynamics with quarantine, isolation, and environmental viral load | 2021 |

| 5 | Shahzad, F; Du, JG; Khan, I; Ahmad, Z; Shahbaz, M | Untying the precise impact of COVID-19 policy on social distancing behavior | 2021 |

| 6 | Qiang, XL; Aamir, M; Naeem, M; Ali, S; Aslam, A; Shao, ZH | Analysis and forecasting COVID-19 outbreak in Pakistan using decomposition and Ensemble model | 2021 |

| 7 | Khan, A; Bibi, A; Khan, KS; Butt, AR; Alvi, HA; Naqvi, AZ; Mushtaq, S; Khan, YH; Ahmad, N | Routine pediatric vaccination in Pakistan during COVID-19: How can healthcare professionals help? | 2020 |

| 8 | Kazi, AM; Qazi, SA; Khawaja, S; Ahsan, N; Ahmed, RM; Sameen, F; Mughal, MAK; Saqib, M; Ali, S; Kaleemuddin, H; Rauf, Y; Raza, M; Jamal, S; Abbasi, M; Stergioulas, LK | An artificial intelligence-based, personalized Smartphone App to improve childhood immunization coverage and timelines among children in Pakistan: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial | 2020 |

| 9 | Chandir, S; Siddiqi, DA; Mehmood, M; Setayesh, H; Siddique, M; Mirza, A; Soundardjee, R; Dharma, VK; Shah, MT; Abdullah, S; Akhter, MA; Khan, AA; Khan, AJ | Impact of COVID-19 pandemic response on uptake of routine immunizations in Sindh, Pakistan: An analysis of provincial electronic immunization registry data | 2020 |

| 10 | Naik, PA; Yavuz, M; Qureshi, S; Zu, J; Townley, S | Modeling and analysis of COVID-19 epidemics with treatment in fractional derivatives using real data from Pakistan | 2020 |

| 11 | Ullah, S; Khan, MA | Modeling the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on the dynamics of novel coronavirus with optimal control analysis with a case study | 2020 |

| 12 | Kakakhel, MA; Wu, F; Khan, TA; Feng, H; Hassan, Z; Anwar, Z; Faisal, S; Ali, I; Wang, W | The first two months epidimiological study of COVID-19, related public health preparedness, and response to the ongoing epidemic in Pakistan | 2020 |

| 13 | Yousaf, M; Zahir, S; Riaz, M; Hussain, SM; Shah, K | Statistical analysis of forecasting COVID-19 for upcoming month in Pakistan | 2020 |

| 14 | Anjum, FR; Anam, S; Rahman, SU | Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): new challenges and new responsibilities in developing countries | 2020 |

| 15 | Zubair, K; Luqman, M; Ijaz, F; Hafeez, F; Aftab, RK | Practices of general public towards personal protective measures during the coronavirus pandemic | 2020 |

| 16 | Iqbal, Z; Aslam, MZ; Aslam, T; Ashraf, R; Kashif, M; Nasir, H | Persuasive power concerning COVID-19 employed by premier Imran Khan: A socio-political discourse analysis | 2020 |

| 17 | Abbas, Q., Mangrio, F. and Kumar, S. | Myths, beliefs, and conspiracies about COVID-19 vaccines in Sindh, Pakistan: An online cross-sectional survey | 2021 |

| 18 | Abid, K., Bari, Y. A., Younas, M., Tahir Javaid, S., & Imran, A. | Progress of COVID-19 epidemic in Pakistan | 2020 |

| 19 | Farooq, F., Khan, J., and Khan, M. U. G. | Effect of lockdown on the spread of COVID-19 in Pakistan | 2020 |

| 20 | Haqqi, A., Awan, U. A., Ali, M., Saqib, M. A. N., Ahmed, H., & Afzal, M. S. | COVID-19 and dengue virus coepidemics in Pakistan: A dangerous combination for an overburdened healthcare system | 2021 |

| 21 | Khalid, A. and Ali, S. | COVID-19 and its challenges for the healthcare system in Pakistan | 2020 |

| 22 | Khan, Y. H., Mallhi, T. H., Alotaibi, N. H., Alzarea, A. I., Alanazi, A. S., Tanveer, N., & Hashmi, F. K. | Threat of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Pakistan: The need for measures to neutralize misleading narratives | 2020 |

| 23 | Khattak, F. A., Rehman, K., Shahzad, M., Arif, N., Ullah, N., Kibria, Z., Arshad, M., Afaq, S., Ibrahim, A. K., & ul Haq, Z. | Prevalence of parental refusal rate and its associated factors in routine immunization by using WHO Vaccine hesitancy tool: A cross-sectional study at district Bannu, KP, Pakistan | 2021 |

| 24 | Saqlain M, Munir MM, Rehman SU, Gulzar A, Naz S, Ahmed Z, Tahir AH, Mashhood M. | Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers among healthcare workers regarding COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey from Pakistan | 2020 |

| 25 | Shoukat, A. and Jafar, M. | Scarce resources and careless citizenry: Effects of COVID-19 in Pakistan. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, Special Edition: COVID-19 Life Beyond | 2020 |

| 26 | Umair, M., Ikram, A., Salman, M., Alam, M. M., Badar, N., Rehman, Z., Tamim, S., Khurshid, A., Ahad, A., Ahmad, H., & Ullah, S. | Importation of SARS-CoV-2 variant B. 1.1. 7 in Pakistan | 2021 |

| 27 | Zakar, R., Yousaf, F., Zakar, M., & Fischer, F. | Socio-cultural challenges in the implementation of COVID-19 public health measures: Results from a qualitative study in Punjab, Pakistan | 2020 |

5 ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

By synthesizing the literature, we identified salient themes and categories (see Table 3). The dominant theme, that is, “the situation of COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan” emerged along with two sub-themes, that is, hesitancy and inequality. Peoples’ hesitation in getting vaccinated is further broken down into two categories, namely conspiracy theories and religious beliefs. Inequality in terms of unfair distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine is generally associated with policy implications and accessibility. We present the description of thematic analysis in the subsequent sections.

| Theme | Sub-themes | Categories | Sub-categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| The situation with respect to COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan | COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy | Conspiracy theories | |

| Religious beliefs | |||

| COVID-19 vaccine inequality | Policy implications | ||

| Accessibility |

- Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

6 COVID-19 VACCINE HESITANCY IN PAKISTAN

Vaccine hesitancy is a universal phenomenon that exists in both developed and developing countries (Khattak et al., 2021). About 90% of the countries reported some degree of vaccine hesitance (Murphy et al., 2021). The WHO declared vaccine hesitancy as one of the 10 major threats to public health worldwide. Though the current literature on vaccine hesitancy is helpful to understand the reasons, it is quite early to understand the attitudes and behaviors for the COVID-19 vaccine in the longer run. Identifying COVID-19 vaccine hesitation could help the effective design of public education campaigns aiming to improve vaccine acceptance behaviors (Murphy et al., 2021).

The conspiracy theories contradict the norms, believed to be influenced by those in power, followed by the minority, and have no scientific evidence to be supported (Freeman et al., 2020). Amidst various conspiracy theories, vaccine hesitancy remains a critical challenge for Pakistan. The country has been facing a similar hesitancy for decades in the case of polio eradication. The factors perceived for hesitation include, but are not limited to, the poor quality of vaccine, perception of vaccine by the clergy as “infidel vaccine,” rumors about active virus within the vaccine itself and the theory that the vaccines are a Western conspiracy to eradicate Muslim populations. The conspiracy theories around the COVID-19 vaccine are widespread on popular media and reach millions of Pakistanis. For example, a renowned political analyst in Pakistan claimed that the COVID-19 vaccine has nano-chips to control human bodies through the 5G internet. Ex-foreign ministry of Pakistan also made similar disinformant comments accusing the United States of inventing the Coronavirus in the UK labs and then transferring it to China for spread. In Pakistan, social media feeds such conspiracies about the COVID-19 vaccine every day. This builds a public narrative defying the reality of the COVID-19 virus and denial of vaccine safety and efficacy (Khan et al., 2020a).

Gallup Pakistan found that 49% of Pakistanis were hesitant to get vaccinated against COVID-19 (Gallup Pakistan, 2020). This hesitancy was mainly because the vaccines were developed in Western countries. 42% among 46% who were willing to be vaccinated said they would prefer not to take Western-made vaccine. The 5% of the respondents either not responded to this question or were not sure about. Similarly, the conspiracies associated with Bill Gates trying to put a surveillance micro-chip in human bodies for tracking and controlling them (Hadid, 2021) also contribute to the hesitancy in getting vaccinated. Another major factor in the rejection of the Western vaccine is the sense of betrayal resulting from the 2011 CIA operation, which targeted Osama bin Laden whose presence in Abbottabad city was identified using a polio vaccine drive as a cover. Such serious factors would risk the security of health workers administering COVID-19 vaccine as previously the polio vaccine drive has been life-threatening for them particularly in northern areas of Pakistan (Jaafari, 2021).

The fake news about Coronavirus misleads the public understanding of the pandemic resulting in challenges to contain the virus and achieve public confidence in being vaccinated. Many in Pakistan believed that the virus only affects older people. This misconception will lead to ignorance of preventive measures by younger people (Zakar et al., 2020). The politicization of the virus by connecting it to serving Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan’s and Western countries interests further created confusion and misinformation, which led to the denial that there is no Coronavirus. Especially the rumors claiming that government receives a certain amount of money by declaring each death due to COVID-19 fueled the idea among some groups that the virus is a means for the government to ask for funding from the United States and other Western countries. The widespread comments made by Pakistanis include: “There is no coronavirus,” “Is the coronavirus a reality?,” “I have not seen any coronavirus infected person anywhere,” “Coronavirus cannot harm Muslims,” “What coronavirus can do to us?,” “Is the coronavirus a reality or conspiracy of America for selling vaccine and medicines?” The conspiracies about coronavirus were common in rural areas of Pakistan, where a limited number of cases were reported (Shoukat & Jafar, 2020).

Malik et al. (2021) argue that some religious leaders have hijacked religion in a predominantly Muslim country and used their interpretation to claim that Sharia law does not allow vaccination against COVID-19 and other chronic diseases. Yet another significant religion-related challenge for Pakistanis is the concept of “Halal.” Just as kosher is important to Jewish people, Halal is essential for Muslims. Muslims do not use ingredients forbidden in Islam, such as pork. Many people are concerned about the ingredients used in the production and development of vaccines. It is precisely, for this reason, the representatives of the high clerical council in Indonesia—a country with the largest Muslim population, visited China’s Sinovac COVID-19 vaccine factory to conduct a halal audit and declared that vaccine as halal, permitting Muslims to take the Chinese Sinovac COVID-19 vaccine.

A 2019 non-COVID vaccination study found Pakistan among 10 countries with the least acceptance to the vaccines (Shah, 2021). As quoted by Zakar et al. (2020) one participant in the survey said: “If it is in my kismet [fate] written that I will get infected with the virus, then nothing can stop it. So, we must trust in Allah. Nothing will happen.” Another participant in the same study said: “Allah is not happy from us. This is a wrath of Allah. We need to give more sadaqa [spend money on poor to make Allah happy].”

Experts identify the misinformation and hardline religious beliefs among significant factors of people’s mistrust in vaccines like COVID-19. Apart from myths about the COVID-19 vaccine for not being halal (denoting or relating as prescribed by Islamic law) due to the potential use of pork gelatin and human fetus tissues, many Pakistanis do not want to take Chinese vaccines due to the conspiracies of the vaccine being not effective. Others do not want to take the AstraZeneca vaccine as it is being manufactured in India. Social media, particularly WhatsApp, has been the major source of such misinformation around the COVID-19 vaccination in Pakistan (Maryam, 2021). The vaccine hesitancy in Pakistan is spread through inauthentic information spread on social media, which has become the source of news for millions in the country. The low level of critical social media literacy has been contributing factor of info-demic in the country about COVID-19 and its preventive measures like vaccination (Malik et al., 2021).

In addition to limited awareness/knowledge and religious beliefs, another major factor hindering the acceptance of explanation is the preference for traditional methods of cure and reliance on spirituality and prayers (Larson et al., 2015). Dube et al. (2013) also included limited awareness as one of the six key factors causing vaccine hesitancy. The other five factors are the nature of an experience with a vaccine, perceived importance of being vaccinated, the level of trust in vaccine, subjective norms related to a particular vaccine, and religious or moral convictions. Khan et al. (2020b) argue that in a country with a fragile healthcare system and economic turmoil of lockdown, vaccinating the masses could be the only way to limit the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet others potential reasons for vaccine hesitancy could be fears of potential side effects in the future, limited supply of vaccine, lack of trust in vaccines’ effectiveness, misconceptions of not being affected by COVID-19, and inability to afford the vaccine (Robertson et al., 2021). The video of a nurse collapsing after vaccination and the news about death after vaccination fueled the conspiracies against COVID-19 vaccine but there was no reality in those videos (Asghar, 2021).

7 COVID-19 VACCINE-INEQUALITY IN PAKISTAN

Like many other developing countries, Pakistan lacks pharmaceutical infrastructure and purchasing power, thus, it relies on its allies and other humanitarian programs to get vaccination support. It is evident that the allies tend to harvest political influence and solidarity from such support to the poor nations. In the case of Pakistan, the Chinese vaccine companies agreed to supply the vaccine for one-fifth of the population on the condition that Pakistan allows vaccine trials for the Chinese vaccines. It is unclear whether Pakistan would have to pay any additional costs, but vaccine provision certainly enhanced the Chinese diplomatic interests in Pakistan (Shah, 2020). Approximately 17,500 Pakistani volunteers were recruited for the trials of China’s CanSino vaccine (Mangi, 2021). Though Pakistan has started receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, an inclusive vaccination rollout strategy is still missing. Also, educational drives associated with vaccine rollouts, which could educate the masses for its wider acceptability are also missing (Umair et al., 2021). In a country marked by economic disparities, various marginalized and vulnerable groups are at a greater risk of contracting COVID-19. People at the bottom of the hierarchy are forced to work extra hours to serve those in power, pushing them for enhanced interactions and reduced chances of social distancing (Kelly, 2020).

In an interview on April 27, 2021, Health Advisor to the Pakistani Prime Minister confirmed that China had donated 1.7 million doses of the COVID-19 vaccine to Pakistan. The country expects to import about three million doses purchased from another Chinese company named CanSino Biologics (Farooq et al., 2021). The health advisor further confirmed that different deals had been secured to import 30 million purchased doses from other vaccine manufacturers (Sultan, 2021). The country is two million doses from Sinovac, a Chinese vaccine manufacturer, during the last week of May 2021 (APP, 2021). Pakistan is also expecting 45 million doses from the COVAX alliance, 1.2 million of which were received on May 8, 2021 (Baig, 2021; WHO, 2021). The challenge with Chinese and Russian vaccines is their lower level of efficacy compared to Pfizer and Moderna, which have more than 95% efficacy (Umair et al., 2021). It was critical to select the best efficacy vaccine for the Pakistani people to control the pandemic, but the government has leaned towards its political ally China whose vaccines’ lower efficacy may prolong the pandemic in Pakistan.

The lockdowns to control the COVID-19 in Pakistan have seriously effected the masses’ economic capacities, which has become a key factor restricting the affordability of the COVID-19 vaccine. The poverty and economic disparities played a significant role in people not following the lockdown orders and social distancing guidelines. Additionally, denial of the virus was another major factor that hindered preventive measures, which caused the spread of COVID-19 in Pakistan (Zakar et al., 2020).

Pakistan is among a few countries that have allowed the private sector to import and sell the vaccine. AGP Pharma, a private pharmaceutical company, imported 50,000 doses of two-shot Sputnik vaccine from Russia, which was sold quite rapidly (Yeung & Saifi, 2021). The Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) fixed the price of privately imported COVID-19 vaccine as PKR 8449 for two doses of Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine and PKR 4225 per jab for China’s CanSino Biologics vaccine (Wion, 2021). Contrary to the prices fixed by DRAP, the first round of commercial sale, which was of Russian Sputnik V vaccine, went for PKR 12,000 (around USD 80) for two doses. The pharmaceutical company, which imported the first shipment of the COVID-19 vaccine, took the government to the court for not being allowed to charge the maximum price for the Sputnik V vaccine; it won the case. Young Pakistanis who did not fall into eligibility criteria for the free vaccine queued up for the purchase of the vaccine, and 50,000 doses went in a few days. Though private vaccines are available in the market, not everyone can afford to get two shots for USD 80, which is four times higher than the international market. (Hassan, 2021). The cost for an average family of five will be USD 400 which might be more than many families in the lower strata earn in a month.

Baraniuk (2021), while analyzing the situation of global vaccine allocation for developing countries, argues, “by the time we board, they were already seated, with champagne in their hands.” He expressed concern over global vaccine inequality. While most Western nations started being vaccinated, the global South neither had the COVID-19 vaccination nor strategies for the procurement of the vaccine. As per the current manufacturing plans of 13 authorized COVID-19 vaccine companies, a quarter world’s population will remain unvaccinated until the end of 2022. Although Covax, the global vaccine alliance for COVID-19, has secured two billion doses for 2021, vaccine nationalism has significantly affected the supply and timeline targets for the potential beneficiary 92 low-and middle-income countries.

Other significant factors for delayed vaccination of people in the Global South include but are not limited to the influence of conspiracy theories against COVID-19, hesitation based on religious factors, fear of side effects, lack of education, and above all, inadequate infrastructure to store and roll out the vaccine (Figure 4).

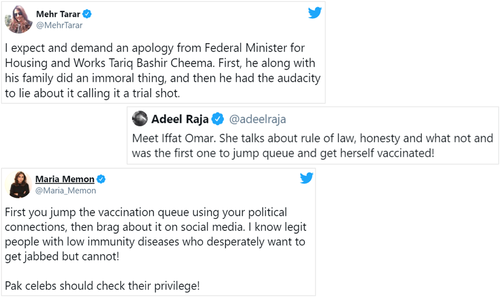

The corruption of some members of the Pakistani elite has posed a significant challenge in the equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine. Those in power have either used money as bribes or political pressures or threats to the health officials administering the COVID-19 vaccine to gain access to the COVID-19 vaccine doses for themselves and their loved ones (Hadid, 2021). Dawn News leaked one such story where the family and friends of the Federal Ministry of Housing (Tariq Bashir Cheema) received the COVID-19 vaccine at the minister’s home when the first shipment of free vaccine arrived in the country (Dawn News, 2021).

Moreover, the already marginalized religious minorities in Pakistan are further away from getting COVID-19 vaccinated. They have been experiencing allegations and discrimination during the pandemic. Since the COVID-19 reached Pakistan with Shia pilgrims returning from Iran, people named the Coronavirus as “Shia virus.” There also have been rumors about incidents of Muslim aid workers mobilizing Hindus to convert to Islam if they want to receive humanitarian aid in the pandemic. Such incidents push the religious minorities farther away from the equitable supply of COVID-19 vaccine if/when it becomes available for the public in Pakistan (Mirza, 2020).

8 STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS

Initially, the British Pakistanis were hesitant to take the COVID-19 vaccine due to fears of potential current or future side effects. However, once their confidence was restored in the vaccine’s efficacy, they expressed willingness to take the vaccine. We argue that awareness and education can lead to enhanced acceptance of the vaccination against COVID-19 in Pakistan. It is critical for a successful vaccine rollout plan to understand who intends to take the vaccine and who has hesitance or concerns. According to the expert advice, the control of the COVID-19 pandemic requires somewhere from 67% to 80% vaccine uptake. Vaccine hesitancy can be a major hindrance in controlling the pandemic (Robertson et al., 2021). The WHO acknowledged and defined vaccine hesitancy as “delay in acceptance or refusal of safe vaccines despite availability of vaccination service.” Vaccine hesitancy can play a crucial role, given the novel nature of COVID-19 makes it unclear when this disease will disappear (Yousaf et al., 2020).

Demographic and contextual factors play an important role in vaccine acceptance rates. Malik et al. (2021) found that the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was influenced positively by age, female gender, and single marital status. Among different ethnic groups in Pakistan, Pashtuns had the highest acceptance for the COVID-19 vaccine, and Balochi has the lowest. Among vaccine-hesitant, the females were more likely to give religious reasons whereas the males were concerned with the vaccine’s effectiveness and its potential side effects.

Abbas et al. (2021) found lower education levels as a significant factor in believing in myths related to COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan, such as believing that the vaccine is a ploy to make Muslims infertile. Since public confidence is vital to the success of any immunization program, the increased public awareness is critical for vaccine acceptance. The vaccine acceptance behaviors are contextual; they rely on the level of public education campaigns led by the vaccine providers, government institutions, politicians, and civil society activists. When the vaccine-hesitant individuals do not receive enough attention or knowledge from health authorities, their level of hesitancy multiplies with everyday conspiracy theories. It results in public denial of the vaccine and hence creates severe challenges for the vaccine rollout. Examples include the resistance to the polio vaccine in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and neighboring Afghanistan (Larson et al., 2015). The Pakistani government must take public education as the primary measure of prevention from the rapid increase of COVID-19 and increased vaccine acceptability (Khalid & Ali, 2020). Researchers and sociologists can play an essential role in informing the government and policymakers about public attitudes related to COVID-19 vaccination (Eskola et al., 2015).

While the importance of education and research is undeniable, another neglected but critically important avenue is proper religious education. Pakistan is a predominantly Muslim country, but unfortunately, religious education has mostly been hijacked by those who have not studied religion. While masses are provided disinformation by quack religious scholars about Halal versus Haraam (what is allowed in Islam vs. what is forbidden), they do not mention that in actuality, Islam promotes taking strict measures to prevent the spread of chronic diseases. Prophet Muhammad (SAW) preached for social distancing, quarantine, and travel bans during pandemics and asked for frequent handwashing during the day. There are numerous examples of quarantine and hygiene in the Islamic religion. Such Islamic measures complement current medical advice for the prevention of COVID-19. Religious education can teach its followers that Islam obliges them to protect themselves from chronic diseases like COVID-19 and prevent the spread by adopting the necessary measures (Hussain, 2021).

Traditional media outlets and social media platforms can also help overcome vaccine hesitancy by engaging medical professionals rather than airing biased commentaries or political views on COVID-19. The government and civil society activists should educate the masses to question the authenticity of information they receive when they refuse the COVID-19 vaccine (Khan et al., 2020a). There is a need for the Pakistani government to launch an expanded public educational outreach campaign to disseminate accurate and honest information about the spread of Coronavirus to encourage vaccine acceptance for public safety. The PEMRA, Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority, could issue guidelines for media platforms to share and promote reliable information on the COVID-19 vaccine (Yousaf et al., 2020). The government must take strategic and prioritized steps to counter the misinformation and disinformation against the COVID-19 vaccine; and educate the masses against myths and false assurances, not affirming misperceptions, and connecting to the common good of public health (MacPherson, 2020).

Medical professionals and social researchers should come forward to counter the vaccine-defying narratives and educate the masses with scientific evidence. It can help counter the falsehood about the COVID-19 vaccine, rumors, and disinformation and challenge the misleading narratives. There is an urgent need to engage religious scholars who have considerable influence on the Pakistan masses to create awareness about the severity of Coronavirus and encourage COVID-19 vaccination. Religious scholars can draw on religious arguments to creating awareness which may help in defying the hesitant behaviors resulting from conspiracy theories. Lessons learned from incorporating religious scholars in promoting the polio vaccine in Pakistan can be applied to endorsing the COVID-19 vaccine (Zakar et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the field staff of the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in Pakistan, in collaboration with UNICEF and WHO, can play a vital role in educating the grassroots communities on COVID-19 vaccination’s importance for individuals, their families, and the country (World Health Organization, 2013). Jarrett et al. (2015) conducted a systemic review of the literature and found similar recommendations to overcome vaccine hesitancy among the masses. The most successful strategies listed by Jarret et al. (2015) included the prioritized reach to the unvaccinated or under-vaccinated populations and educating the masses on vaccine importance for the public good. They further suggested the mobilization of community influence, utilization of social media and mass media for public education on vaccination program, and engagement of religious leaders to endorse the vaccination for the masses. Malik et al. (2021) also confirmed that anti-vaccine religious narratives can only be countered through the engagement and public support by like-minded religious leaders. Since the major COVID-19 vaccines developed in the Western countries and with the highest efficacy—Pfizer, Modern, and AstraZeneca—also confirmed that their vaccines do not contain pork products (Times of India, 2020), the government of Pakistan should engage like-minded religious leaders, social media influencers, and celebrities to disseminate the knowledge for COVID-19 vaccine confidence among Pakistanis (Hadid, 2021). The suspicion of COVID-19 vaccine for not being halal should balance with fact that “protecting others is an obligation” (Kadri, 2021).

9 CONCLUSION

After conducting a thorough review of the literature, our conclusions are in sync with the nascent available literature on this current but important topic. For example, we agree with Jarrett et al. (2015) recommendations to counter vaccine hesitancy among the masses especially prioritizing reach to the unvaccinated or under-vaccinated populations. We also emphasize educating the masses on vaccine importance. Several other strategies such as mobilization of influential people in communities, availing social and traditional media for public education on the vaccination program can also play a vital role in encouraging vaccination acceptance levels. Another under-researched area that can play an important part is the engagement of religious leaders to endorse the vaccination for the masses. We agree with Malik et al. (2021) that anti-vaccine religious narratives can be countered most effectively by engaging religious leaders and scholars in the country.

Major vaccine producers such as Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca have confirmed their vaccines do not contain pork products (Times of India, 2020). The Pakistani government needs to engage religious leaders/scholars to disseminate the knowledge of the Halal/kosher nature of the COVID-19 vaccine to restore confidence among Pakistanis (Hadid, 2021). The suspicion of the COVID-19 vaccine for not being halal should balance with the fact that “protecting others is an obligation” (Kadri, 2021). We noticed a significant gap in the literature when it comes to highlighting the problems associated with the use of imported terminology related to the spread COVID-19 virus in the context of Pakistan. Most laboratories and doctors continue to use Western terminology such as positive tests and negative tests when providing information to the public. This has given rise to much confusion amongst people as a positive test is sometimes taken to indicate everything “being good.” In some instances, when people received a positive test report, they continued mingling with others, thinking that all was good. Perhaps more research is needed on the use of context-bound terminology to deal with global pandemics.

Our study reviews the mechanism for equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccination among the communities in Pakistan. The literature is limited as this is a new area of research. A synthesis of literature indicates that people are reluctant to use vaccines due to conspiracy theories and religious beliefs. Inequality appears as a barrier to getting a vaccine due to ineffective policy implications and lack of accessibility to all social groups. Further research is required to empirically examine the factors that support and impede the equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine to ensure equality among all social groups in multiple regions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors acknowledge institutions, researchers, blog writers and news portals who have published content related to topic of study. This study received no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made equal contributions.

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- , , & (2021). Myths, beliefs, and conspiracies about COVID-19 Vaccines in Sindh, Pakistan: An online cross-sectional survey. Authorea. https://doi.org/10.22541/au.161519250.03425961/v1

- , , , , & (2020). Progress of COVID-19 epidemic in Pakistan. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 32(4), 154– 156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539520927259

- , , & (2020). Novel Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): New challenges and new responsibilities in developing countries. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 16(10), 2370– 2372.

- (2021). COVID-19: Dangerous side effects of vaccines? https://tribune.com.pk/story/2288067/covid-19-dangerous-side-effects-of-vaccines

- Associated Press of Pakistan – APP. (2021). Another 2 million doses of Sinovac shots flown in from China. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2301192/1

- (2021). Doctors struggle to convince Pakistanis to get the vaccine shot. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/02/25/pakistan-COVID-vaccines-obstacles-covax/

- (2021). How to vaccinate the world against COVID-19. The BMJ, 372(211):bmj.n211. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n211

- , , & (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: Correlates in a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Australian population. PLoS One, 16(3), e0248892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248892

- , , & (2020). COVID-19 vaccines: Getting anti-vaxxers involved in the discussion. World Development, 136, 105177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105177

- , , , , , , , , , , , , & (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic response on uptake of routine immunizations in Sindh, Pakistan: An analysis of provincial electronic immunization registry data. Vaccine, 38(45), 7146– 7155.

- (2021). COVID-19 vaccine tracker. Regulatory Focus. www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2020/3/COVID-19-vaccine-tracker

- Dawn News (2021). Minister under fire for allegedly using influence to get family vaccinated for COVID-19. www.dawn.com/news/1615465

- , , , , , & (2013). Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8), 1763– 1773.

- , , , & (2015). How to deal with vaccine hesitancy? Vaccine, 33(34), 4215– 4217.

- , , & (2020). Effect of lockdown on the spread of COVID-19 in Pakistan. Physics and Society, Cornell University. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.09422

- , , & (2021). Pakistan to get 3 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines from China’s CanSino next month. www.reuters.com/world/india/pakistans-outgoing-finmin-tests-positive-COVID-19-hospitals-near-capacity-2021-03-30/

- , , , , , , , , , , , & (2020). Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychological Medicine, 1– 13.

- Gallup Pakistan. (2020). Coronavirus attitude tracker survey 2020, Wave 9. https://gallup.com.pk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Gallup-Covid-Opinion-Tracker-Wave-9-pdf.pdf

- (2021). Pakistan’s vaccine worries: Rich people and conspiracy theorists. NPR. www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/01/29/961258106/pakistans-vaccine-worries-rich-people-and-conspiracy-theorists

- , & (2020). COVID-19 and the cost of vaccine nationalism. RAND Corporation. www.rand.org/randeurope/research/projects/cost-of-COVID19-vaccine-nationalism.html

- , , , , , & (2021). COVID-19 and dengue virus coepidemics in Pakistan: A dangerous combination for an overburdened healthcare system. Journal of Medical Virology, 93(1), 80– 82.

- (2021). Young Pakistanis rush to purchase Russian vaccine as private sales open. www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-pakistan-vaccine/young-pakistanis-rush-to-purchase-russian-vaccine-as-private-sales-open-idUSKBN2BR0LH

- (2021). Some Muslims are reticent to accept a COVID-19 vaccine—but it’s not because Islam is “anti-science.” ABC Religion and Ethics. www.abc.net.au/religion/overcoming-muslim-reticence-toward-COVID-vaccine/12927958

- , , & (2020). COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. International Journal of Translational Medical Research and Public Health, 4(1), 37– 49. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijtmrph.139

- , , , , , & (2020). Persuasive power concerning COVID-19 employed by Premier Imran Khan: A socio-political discourse analysis. Register Journal, 13(1), 208– 230.

- (2021). The biggest challenge for vaccine workers in Pakistan? Staying alive. The World. www.pri.org/stories/2021-03-02/biggest-challenge-vaccine-workers-pakistan-staying-alive

- , , , , & (2015). SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy–A systematic review. Vaccine, 33(34), 4180– 4190.

- (2021). For Muslims wary of the COVID vaccine: There’s every religious reason not to be. The Guardian. www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/feb/18/muslims-wary-COVID-vaccine-religious-reason

- , , , , , , , , & (2020). The first two months epidimiological study of COVID-19, related public health preparedness, and response to the ongoing epidemic in Pakistan. New Microbes and New Infections, 37, 100734.

- , , , , , , , , , , , , , , & (2020). An artificial intelligence–based, personalized smartphone app to improve childhood immunization coverage and timelines among children in Pakistan: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 9(12), e22996.

- (2020). COVID-19 and the rights of members of belief minorities. Institute of Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/15891/908_COVID_and_religious_minorities.pdf?sequence=3%26isAllowed=y

- , & (2020). COVID-19 and its challenges for the healthcare system in Pakistan. Asian Bioethics Review, 12, 551– 564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-020-00139-x

- , , , , , , , , & (2020a). Routine pediatric vaccination in Pakistan during COVID-19: How can healthcare professionals help? Frontiers in Pediatrics, 8, 859.

- , , , , , , , , , , , & (2021). SARS-CoV-2 genome from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan. ACS Omega, 6(10), 6588– 6599.

- , , , , , , & (2020b). Threat of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Pakistan: The need for measures to neutralize misleading narratives. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(2), 603– 604.

- , , , , , , , , , & (2021). Prevalence of parental refusal rate and its associated factors in routine immunization by using WHO Vaccine Hesitancy tool: A cross sectional study at district Bannu, KP, Pakistan. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 104, 117– 124.

- , , , & (2015). Measuring vaccine confidence: Introducing a global vaccine confidence index. PLoS Currents, 7.

- , & SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161– 4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

- (2020). What is the world doing about COVID-19 vaccine acceptance? Journal of Health Communication, 25(10), 757– 760. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1868628

- , , & (2021). Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan among health care workers. Preprint. www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.23.21252271v1

- (2021). China vaccine maker CanSino to offer Pakistan 20 million doses. Bloomberg. www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-22/china-vaccine-maker-cansino-to-offer-pakistan-20-million-doses

- (2021). Pakistan: Conspiracy theories hamper COVID vaccine drive. www.dw.com/en/pakistan-conspiracy-theories-hamper-COVID-vaccine-drive/a-56853397

- , , , , , , , , , , , & (2021). Investigating connections between COVID-19 pandemic, air pollution and community interventions for Pakistan employing geoinformation technologies. Chemosphere, 272, 129809.

- (2020). COVID-19 fans religious discrimination in Pakistan. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/COVID-19-fans-religious-discrimination-in-pakistan/

- , , , , , , , , , , , , , , & (2021). Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1– 15.

- , , , , & (2020). Modeling and analysis of COVID-19 epidemics with treatment in fractional derivatives using real data from Pakistan. The European Physical Journal Plus, 135(10), 1– 42.

- , , , , , & (2021). A fractional order mathematical model for COVID-19 dynamics with quarantine, isolation, and environmental viral load. Advances in Difference Equations, 2021(1), 1– 19.

- Pew Research Center. (2021). Intent to get vaccinated against COVID-19 varies by religious affiliation in the U.S. 10 Facts about Americans and coronavirus vaccines. www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/23/10-facts-about-americans-and-coronavirus-vaccines/ft_21-03-18_vaccinefacts/

- , , , , , & (2021). Analysis and forecasting COVID-19 outbreak in Pakistan using decomposition and Ensemble model. CMC-Computers Materials & Continua, 68(1), 841– 856.

- , , , , , , , & (2021). Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 94, 41– 50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008

- , , , , , , , & (2020). Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers among healthcare workers regarding COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. Journal of Hospital Infection, 105(3), 419– 423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.05.007

- , & (2020). The role of religion in COVID prevention response: Where angels fear to tread. Impakter. https://impakter.com/role-religion-COVID-prevention-response/

- (2020). China to supply coronavirus vaccine to Pakistan. The Wall Street Journal. www.wsj.com/articles/chinato-supply-coronavirus-vaccine-to-pakistan-11597337780

- (2021). COVID-19 vaccination efforts in Muslim nations try to overcome halal concerns. The Wall Street Journal. www.wsj.com/articles/COVID-19-vaccination-efforts-in-muslim-nations-try-to-overcome-halal-concerns-11610197200

- , , , , & (2021). Untying the precise impact of COVID-19 policy on social distancing behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 896.

- , & (2020). Scarce resources and careless citizenry: Effects of COVID-19 in Pakistan. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, Special Edition: COVID-19 Life Beyond. https://www.ijicc.net/images/Vol_14/Iss_6/PUL014_Shoukat_2020_R1.pdf

- , , & (2021). Immuno-informatics approach for B-cell and T-cell epitope-based peptide vaccine design against novel COVID-19 virus. Vaccine, 39(7), 1087– 1095.

- (2021). Interview of Prime Minister’s Health Advisor on April 27, 2021. www.facebook.com/NHSRCOfficial/videos/944198769687429/

- Times of India. (2020). Concerns among Muslims over Halal status of COVID-19 vaccine. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/rest-of-world/concern-among-muslims-over-halal-status-of-COVID-19-vaccine/articleshow/79834189.cms

- , & (2020). Modeling the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on the dynamics of novel Coronavirus with optimal control analysis with a case study. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 139, 110075.

- , , , , , , , , , , & (2021). Importation of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 in Pakistan. Journal of Medical Virology, 93(5), 2623– 2625. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26869

- Wion. (2021). Pakistan Cabinet approves highly expensive prices for COVID-19 vaccines. www.wionews.com/south-asia/pakistan-cabinet-approves-highly-expensive-prices-for-COVID-19-vaccines-372199

- , , , , & (2020). The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 16(9), 2204– 2214.

- World Health Organization. (2013). The expanded programme on immunization. www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/supply_chain/benefits_of_immunization/en

- World Health Organization. (2021). Pakistan receives first consignment of COVID-19 vaccines via COVAX facility. www.emro.who.int/media/news/pakistan-receives-first-consignment-of-COVID-19-vaccines-via-covax-facility.html

- , & (2021). Vaccines sell out in Pakistan as the private market opens, raising concerns of inequality. www.cnn.com/2021/04/12/asia/pakistan-COVID-private-vaccines-dst-intl-hnk/index.html

- , , , , & (2020). Statistical analysis of forecasting COVID-19 for upcoming month in Pakistan. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 138, 109926.

- , , , & (2020). Socio-cultural challenges in the implementation of COVID-19 public health measures: Results from a qualitative study in Punjab, Pakistan. https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-122145/v1/c13b5c6b-07bc-49f1-98c7-807498a66734.pdf

- , , , , & (2020). Practices of general public towards personal protective measures during the coronavirus pandemic. Annals of King Edward Medical University, 26(Special Issue), 151– 156.