The QAnon Movement Isn’t Dead. From What I Saw in Dallas, It’s Just Evolving.

Politics & Policy

The outlandish conspiracy theory has made legions of believers into political activists. And the Texas GOP benefits from that.

Photograph by Shelby Tauber

In the year 1190, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, amid an arduous overland trek to Jerusalem, arrived with his army at the Saleph River, in what is today southern Turkey. He drowned in waist-high water, according to some accounts, weighed down by his armor. Crusades are a dangerous business.

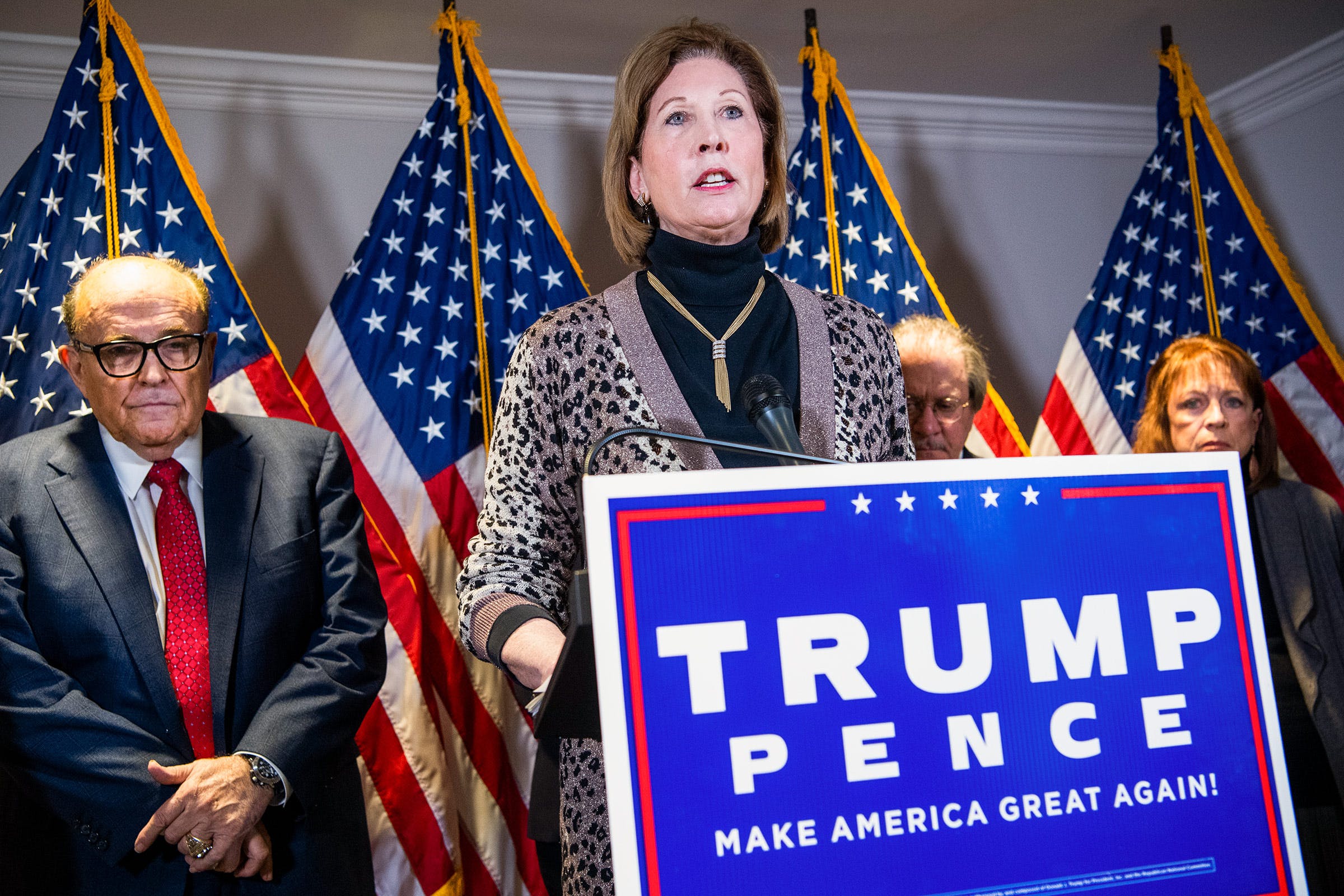

Sidney Powell, crusading lawyer of Dallas, is drowning much closer to home. It’s late May, Memorial Day weekend, and she’s speaking to a crowd of nearly a thousand self-described truth seekers. “Truth is the armor of God,” she tells the rapt audience at Eddie Deen’s Ranch, a kitschy wedding and event venue in an awkward corner of the city’s gargantuan convention-center complex. “Deception is destroying this country,” she says. Heathens and unbelievers are “terrified, absolutely terrified of the truth.”

Powell is one of the stars of the “For God & Country Patriot Roundup,” a three-day conference with ties to QAnon where the followers of Q will ponder, among other weighty subjects, the dangerous infiltration of Jews and members of the Chinese Communist party into American institutions; the nation’s secret space program; the growing number of karate dojos owned by child-traffickers; and the possibility of kickstarting a military coup to remove Satan-worshipping pedophiles from government. In between, they’ll hear from prominent figures in the Texas GOP. Boxed lunches will be provided.

Of the tens of speakers, though, only Powell is in a position to deliver the catharsis the crowd needs. She won fame as the most animated member of former president Donald Trump’s legal team during the interregnum between the 2020 election and Joe Biden’s inauguration—so animated that Trump eventually disavowed her. For those who believe the last election was a fraud of world-historic proportions, Powell was the keeper of the “kraken,” a mythological sea monster, which would be “unleashed” at any moment, with undeniable evidence of a sweeping conspiracy, and Trump would be returned to the White House. That, of course, did not happen. One might expect that her biggest fans would be wondering why.

This is the biggest Q get-together since—well, since the storming of the U.S. Capitol building in January, in which five people died. And here’s what Powell’s got that will bring the shaky edifice of the deep state tumbling down: Mike Lindell—that’s the proprietor of MyPillow.com, for the uninitiated—has been working “on evidence of actual votes being flipped,” Powell says. “That’s still being verified.” The election audit currently underway in Arizona, she promises, will “find evidence of four hundred to five hundred thousand fraudulent votes for Biden.” That would be enough evidence for the legislature to “decertify the election.” That, combined with events elsewhere, could mean that Trump would be reinstated as president in August.

Powell does not have much to show for her efforts. Even more grimly, she tells the audience of QAnon adherents, there might be no “storm” coming. “There are no military tribunals that are going to solve this problem for us,” she says. “It’s going to take every one of us rolling up their sleeves.” Be the Q you want to see in the world, in other words.

Then she exits the room, leaving only her well-staffed merch table, which, in Eddie Deen’s Western-themed space, sits in front of two large, light-up cacti. Copies of Licensed to Lie: Exposing Corruption in the Department of Justice are going for $50. Signed copies are $100, with a “personalized message” for a mere $50 more. The real steal, though, are the “Release the Kraken”–themed tote bags and T-shirts, which go for $30 and $35, respectively. Powell’s table sits next to another for a company called Patriotic Strong, which promises to cure chronic pain with things it calls “quantum energy patches.”

The emcee bounds onto the stage after Powell departs. “Are you guys ready to party?” he shouts. “Do patriots know how to party?”

Is QAnon finished? Many would like to think so. “QAnon’s coherence, allure and leadership are over,” wrote columnist Virginia Heffernan in the Los Angeles Times in June. Q itself—the person or persons whose anonymous posts fueled the QAnon movement—vanished like a puff of vape smoke earlier this year, after too many promises made to believers soured. Hundreds of the rioters who stormed the Capitol have been arrested, including the infamous horn-hatted Q Shaman. When Biden was inaugurated, part of the palpable sense of relief among his half of the country was that they would no longer have to think about guys with names like “the Q Shaman.” Surely, their time had passed.

Maybe not. “What we’re seeing now is a kind of second iteration of the movement, under Biden. It looks and sounds slightly different, but the energy and larger worldview is still there,” says Jared Holt, a fellow at the Digital Forensic Research Lab of the Atlantic Council, who has spent much of the last few years following the QAnon movement. It might be less prominent in the discourse since its peak after the election, Holt says, but there’s “no shortage of individuals radicalized by QAnon floating in the political atmosphere, and some of them have expressed aspirations for cementing influence in the broader GOP.” That means running for party positions, school boards, and other local offices—the same play enacted successfully by the tea party a decade ago. The left-wing watchdog group Media Matters for America recently tallied 38 Q-friendly candidates running (most as Republicans) for congressional seats. Three of them are in Texas.

In February, a poll by the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute found that 29 percent of Republican voters agreed with the proposition, central to QAnon beliefs, that “Trump has been secretly fighting a group of child sex traffickers that includes prominent Democrats and Hollywood elites.” According to the same poll, more than two thirds of Republicans agree with Powell that massive fraud put Biden in power. And Powell’s assertion that Trump could be reinstated as early as August, echoed by Trump himself, has taken on a life of its own. On June 26, at Trump’s first rally since leaving office, some of his supporters predicted violence if the reinstatement didn’t happen.

The conference at Eddie Deen’s is a rare opportunity to gather with Q adherents in person. Some eight hundred attendees paid at least $500 each to attend the conference, which consists primarily of a long list of speakers, many of them inexperienced, and some free food. (Attendees could purchase VIP tickets, which allowed them to enjoy a happy hour with General Michael Flynn, Trump’s disgraced former national security adviser, for $1,000.) They have sacrificed a lot of time, and a lot of money, to be here.

There are two kinds of speakers at the event: those who seem to believe, and those for whom the belief of the former group is useful. The first group includes the social-media influencers that constitute the major generative force of the Q phenomenon. If Q is the Messiah, these are his apostles. Now that Q has disappeared, they are left to reinterpret and keep alive Q’s 4,953 posts and find ways to turn his message into something future generations can inherit.

Brad Getz, a former New York City construction surveyor, came to Eddie Deen’s to give a sermon, a dense disquisition on Edward Bernays, an Austrian public-relations pioneer whom he identifies as one of the New World Order’s first propaganda chiefs. But first, a reading from the book of 8kun, the website formerly known as 8chan. To steady a wavering heart, return to first principles. “This is post 4462,” Getz begins. “‘Division is man-made. Unity is humanity. Trust yourself. Think for yourself. Only when good people collectively come together will positive change occur.’” How could the media—the liars who say QAnon is a dangerous cult—possibly object to that? They focused on the craziest-sounding tenets of Q eschatology—the idea that JFK Jr. is still alive and in hiding, waiting to lead a revolution, for example—because they were terrified that the public would read the posts themselves, and hear their “overwhelmingly positive message.” This is a common theme. Just “point one percent of the drops involve pedophilia or satanism,” says Bernie Suarez, a former cohost of 911 Free Fall, a podcast advocating for the proposition that the World Trade Center was brought down by explosives.

Even the speakers who embrace the more challenging parts of the Q belief system seem to be backing away—if only to better serve the mission. Influencer Jason Frank takes an admirably pragmatic line. “I don’t always talk about Pizzagate, I don’t always talk about adrenochrome, I don’t always talk about the satanic rituals,” he says. He pauses, choking up. “Because I figured the quicker we could get everyone involved, the quicker we could make it stop.” (Pizzagate is the theory that global elites are engaged in widespread child sex trafficking. The theory centers on Comet Ping Pong, a Washington, D.C., pizzeria and table-tennis bar. Adrenochrome is the material the elites supposedly harvest from murdered children to extend their own lifespans.)

The Q prophecies are in the past. “It doesn’t matter what Q does; it doesn’t matter what Trump does,” Frank says. “We are the storm. We are the plan.”

The other speakers, the professionals, are careful not to engage with the fringier beliefs. Neither do they denounce them. Even Powell, when asked if “Talmudic Judaism is the fist in the glove of the deep state,” gives a scrupulously nonjudgmental reply: “I have no idea.” Several speakers are Trump administration veterans—including George Papadopoulos, a Trump campaign adviser who served jail time for lying to federal investigators—and they stick to the script, telling stories about their tenure.

Texas Republican congressman Louie Gohmert, typically the strangest man in any room he’s in, is here one of the sanest, delivering a stem-winder that ranges from the works of Dostoyevsky and Orwell to the ordeal of ordering meat loaf at Mar-a-Lago to the economic dysfunction of the Soviet Union. But at the end of a lot of riffing, he gets down to business. “Listen,” he says, “we can’t lose sight of the importance of 2022 and 2024 for the preservation of democracy.”

That goes double for Allen West, the recently resigned Texas GOP chair turned gubernatorial candidate, who had the party adopt a slogan—“We Are the Storm”—that comes straight from QAnon’s eschatology. West shares the messianic outlook of QAnon, the belief that he is part of some burgeoning redemption of America. He comes onstage to the tune of Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man.” He gets a rapturous reception.

“I am a walking miracle,” he tells the crowd. When he was running for party chair, he survived a high-speed motorcycle accident on Interstate 35, the kind of crash one isn’t supposed to survive, he says. “God is still on the throne,” he says, and “you have been made for a time such as this.” As he speaks, West is facing criticism from Texas Republicans who say he shouldn’t be here. But he’s preparing a run against Greg Abbott in which he will need every ounce of support he can muster among the party’s activist base. Why wouldn’t he be here?

Flynn, bemoaning the Republican party’s failure to help Trump enough, tells attendees not to give money to the Republican National Committee. Gohmert and West are here to say the opposite: stay with us, stay engaged. Keep voting and volunteering. Whatever else QAnon has done to the brains of the faithful in attendance, it has made them politically active. The GOP as a whole is unlikely to repudiate them, so long as they remain useful. That’s the way the party has dealt with fringe movements and beliefs for a long time: with toleration, from a distance.

The tenets of QAnon are not altogether crazier than the stuff that has been percolating on the far right for decades and that has been seamlessly integrated into the party: Jade Helm, sharia law, the militia movement of the nineties. In 2011, I covered a similar conference held by the Waco Tea Party. At one seminar, a Dallas tea-party activist educated attendees about Executive Order 13575. The numbers, she pointed out to gasps, added up to 21, as in Agenda 21, a United Nations–hatched environmental plan that was then the subject of many conspiracy theories. The order was a Trojan horse, she promised, through which President Obama would take control of the nation’s seed-distribution network—while the UN deployed an army of block captains and informers to crack down on the use of trans fats and fast food. That woman, Katrina Pierson, was a prominent Ted Cruz supporter before becoming the national spokesperson of the Donald Trump presidential campaign.

But at what cost does the party play footsie with this crowd? “How many of you were there on January 6?” Andy Meehan, a Pennsylvania Republican and failed congressional candidate, asks the audience in Dallas. Dozens of hands go up. Their anger should now be directed at the GOP, Meehan says. “The RINO [Republican in Name Only] establishment is killing us, okay? It’s not the Democrats.” He urges the audience to begin taking over the party from below. Then he plays his harmonica.

The most worrying note of the conference is sounded by Flynn. For most of his remarks, he sticks carefully to his script. But on the second day, a man stands up to ask him a question. “I’m a simple Marine,” he says. “Why can’t what happened in Minimar happen here?” He means Myanmar, where the military recently took control from an elected government and set about imprisoning, executing, and torturing the opposition. QAnon has been looking jealously at the coup for months. At least somebody felt the pleasure of rounding up their enemies this year.

Flynn’s response is unambiguous. “No reason,” he says. “I mean, it should happen here.” His reply is met with applause and cheers. It is so over the line that it precipitates an international media frenzy—it is the breakout moment of the conference. But it isn’t enough to scare away West, who gives his speech about an hour later. Once West is done, he invites Flynn back out on stage—whereupon Flynn endorses him for governor. West smiles.

There is much madness in the history of this country. There is so much madness in the history of this corner of downtown Dallas, even. Almost a hundred years to the day before the Patriot Roundup, the Klu Klux Klan marched down Elm Street a few blocks away from Eddie Deen’s. Its klaverns and kleagles and wizards ran the city, so much that they could abduct and torture citizens with impunity. Nearby is Dealey Plaza, where a president was murdered in a sort of Cold War fever dream with a bizarre cast of characters. Between the two is El Centro College, where in 2016 an embittered Afghanistan war veteran shot five police officers before being killed by a police robot. All of this in an area of a few blocks.

On the last day of the conference, while attendees are munching on cinnamon rolls from the breakfast bar, Powell strides back on stage, in her resplendent armor of truth. “The first order of business this morning is to dispel a horrible incident of fake news,” she says. “The fake news has grossly distorted what General Flynn said yesterday in response to a question about Myanmar. There are no circumstances in which he urged the military to take any action to unseat the president.”

Of course, the faithful at this conference believe Trump is the president, so it’s unclear exactly what she’s saying. Powell says the organizers had “the full recording of everything that was actually said.” Flynn’s remarks (which were reported verbatim) were “simply not a fair or accurate representation of the conversation.” The audience, the same audience who cheered what Flynn had said previously, cheers just as hard for the revelation that he didn’t say it.

I’ve had about enough. My head hurting, I take a pamphlet on those quantum energy patches on the way out the door. Powell’s voice booms on the speakers as I walk into the sunlight. “These are the times,” she says, “that try men’s souls.”