Jabs Under Duress: How Moscow’s Mayor is coercing compliance

Riley Waggaman

With Moscow’s hospitals facing unprecedented strain not seen since six months ago, Mayor Sergey Sobyanin has done away with antiquated notions of bodily autonomy and free commerce in order to save the city. Please clap.

Muscovites collectively breathed a sigh of relief when Sobyanin announced last month that due to rising Covid hospitalizations, millions of residents would no longer be trusted with making personal medical decisions for themselves. In sectors such as transport, hospitality and leisure, businesses would need to meet a 60% vaccination quota among employees or risk exorbitant fines.

A few days later, the mayor announced the creation of now-defunct ‘Covid-free’ zones for double-dosed VIPs and Covid-conscious residents: Under the short-lived scheme, those who were fully vaccinated, or had recovered from the virus over the past 6 months, or were able to produce a negative PCR test from the last 72 hours, were eligible to receive a QR code granting them exclusive access to indoor seating in bars and restaurants. Those without these health IDs — the lepers — were banished to outdoor seating areas.

When he unveiled this pioneering public health policy last month, Sobyanin had insisted that the digital health passes would be “necessary to keep people alive.” But starting from July 19 they will no longer be required. They never really caught on and, as a result, nearly 200 businesses in Moscow closed in under 3 weeks.

To the untrained eye, these policies appear potentially coercive — which might reflect poorly on Sobyanin, considering that, historically, extortionary tactics have received 1-star Yelp reviews in the marketplace of ideas.

If he who employs coercion against me could mould me to his purposes by argument, no doubt he would. He pretends to punish me because his argument is strong; but he really punishes me because his argument is weak.”

William Godwin

Maybe that was true way back in the 1700s but human nature has changed a lot since then. Besides, Godwin never had to worry about hospital capacity.

Voluntary vaccination: A simple matter of perspective

A small but noisy band of malcontents has accused Sobyanin of instituting a “compulsory” vaccination regime that somehow runs afoul of basic human rights. But what do the facts, and more importantly, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov, say? Backing the mayor’s new approach to mass inoculation, Peskov insisted that “vaccination is voluntary because you can change your job.”

Peskov seems to have a precise and highly sophisticated understanding of what constitutes compulsory vaccination. Perhaps non-voluntary vaccination is when Peskov knocks on your door with a Kalashnikov and asks politely for you to roll up your sleeve? Perhaps. Whatever it is — it is not what is happening right now.

Dangerous vaccine-hesitant types might say it’s reprehensible to suggest that Muscovites are exercising free power of choice when they are forced to choose between feeding themselves and maintaining control over what goes into their bodies. What’s so reprehensible about it?

Peskov has shrewdly identified a loophole in order to shield Russian authorities from moral considerations — this is what he is paid to do, and he does it very well. With so many Russians now at risk of losing employment, it would be irresponsible at the macroeconomic level to spew groundless aspersions that might undermine the Kremlin spokesman’s own job security.

The science can’t wait

Then there are the worrywarts with their so-called safety concerns.

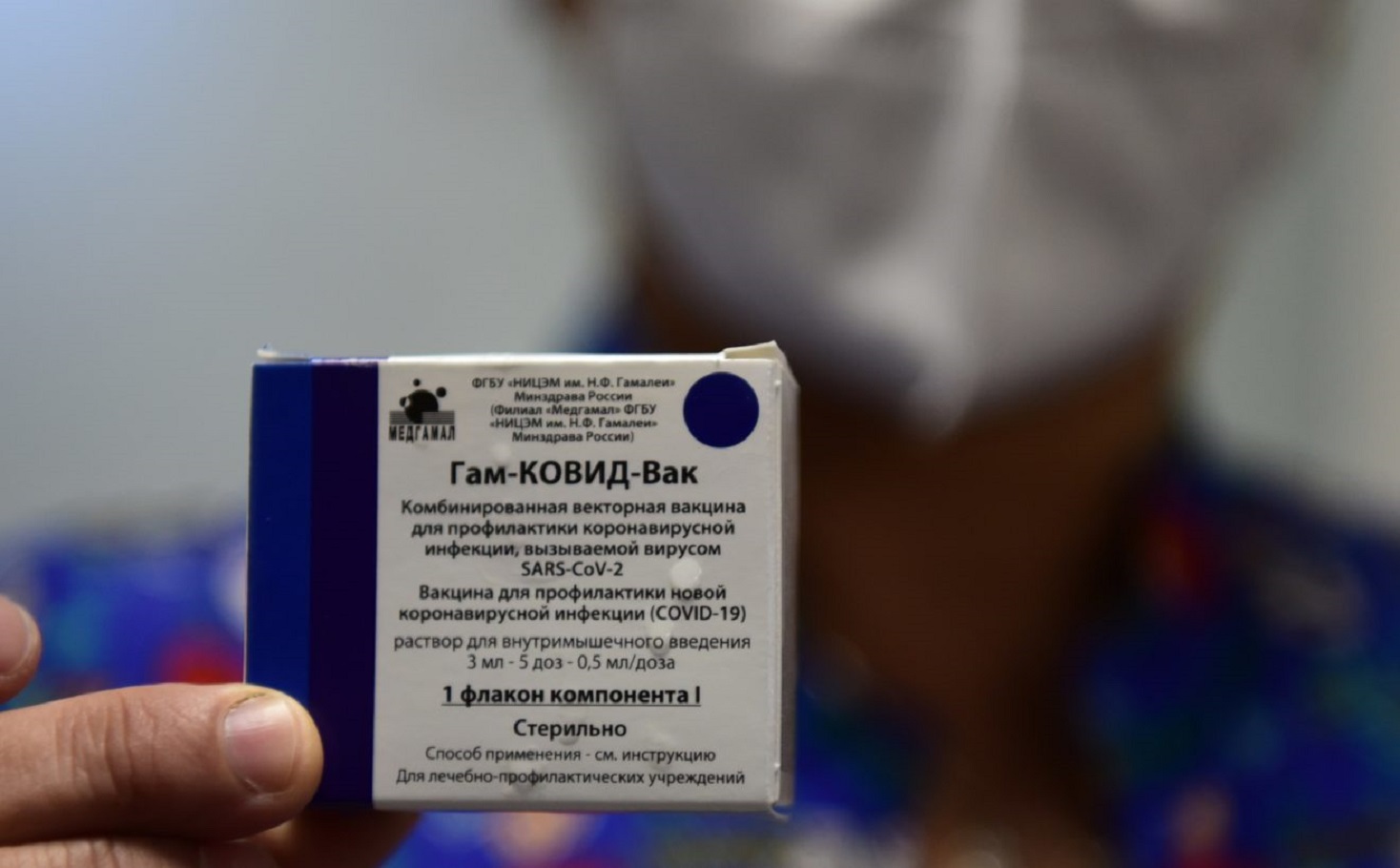

Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine, and nearly every other vaccine on the market, has shown God-like results in its first year of clinical tests. Under ordinary circumstances, only another nine to fourteen more years of trials would be needed to secure regulatory approval for these miracle drugs.

According to protocols set out by the IFPMA, a leading global pharmaceutical lobby, phase I clinical trials alone typically require two years — longer than Covid-19 has even been around to vaccinate against. Phase III trials often last between 5-10 years.

Of course, all of the above remains 100% true today. But the tin foil hatters who object to worldwide emergency vaccine rollouts on ‘safety’ grounds still risk getting checkmated by facts and logic: If these vaccines are so bad, why is literally everyone using them?

For the record: There’s only been one — only one! — global health boondoggle in the past decade in which countries around the world, including Russia, were persuaded to spend lots of money on potentially dangerous vaccines that they probably didn’t need.

In 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic following an outbreak of H1N1 ‘swine flu’, without disclosing that several officials involved in this momentous decision had financial ties to pharmaceutical companies that stood to make huge profits from state-sponsored mass vaccine rollouts.

One of the vaccines rushed out during this period, Pandemrix, was later linked to suspicious cases of narcolepsy in children. Thankfully that particular big pharma blend was not deployed in Russia.

Still, by early 2010, more than a million Muscovites had been vaccinated against swine flu, with media reports warning “refuseniks” that there could be severe consequences for not getting jabbed. Russian doctors also prescribed an anti-swine flu medication called Tamiflu, which was later found to be backed by bogus data.

In the United States, the H1N1 shot was made mandatory for New York healthcare workers. Around 90 million vaccines were administered across the country, but an almost equal number — 70 million — were tossed after demand for the drug dried up. The vaccination program set US taxpayers back by $1.6 billion.

A similarly odious spending spree occurred in Russia. One lawmaker, a retired FSB colonel and member of the Duma’s anti-corruption commission, suggested that Russia had been duped into wasting vast sums at a time when public funds were far from limitless.

“Russia has spent over 4 billion rubles on the fight against the new virus. Taking into account the state of the country’s economy, these funds could be spent on solving other problems, the relevance of which there is no doubt,” the Duma deputy, Igor Barinov, said in November 2009.

The only country that didn’t buy lots of experimental swine flu shots, Poland, insisted that the worldwide vaccination drive was “not honest and not safe.”

But all of this all happened way back in 2009. Global health authorities have changed a lot since then.

The Hermetic cult of hospital capacity

Over the past twelve months or so it suddenly became extremely fashionable for governments to subordinate large swathes of human activity, and of the human experience itself, to “hospital capacity”. In a blog post explaining his “difficult, but necessary and responsible decision” to take custodianship over what needs to go into the bodies of several million Muscovites, Sobyanin pointed to the rapidly deteriorating situation in the city’s hospitals. After all, the city was seeing close to 2,000 hospitalizations per day.

Basic tenets of medical privacy and free commerce needed to be fed through a woodchipper. Sobyanin’s deputy explained why: in 2-3 weeks there would be no beds left for Covid patients. “It’s simple math that puts us in a tight box,” she revealed on June 16. More than 12,000 beds were occupied at the time.

According to the most recent, publicly available information, Moscow currently has somewhere between 20-24 thousand hospital beds reserved for Covid patients. On June 29, occupancy “approached” 15,000 beds, and this number has remained relatively constant since then. In other words: there are at least 20,000 Covid beds with 15,000 of them currently in use — providing a reserve of over 5,000 beds. Occupancy seems to have peaked by the end of June, but the total number of beds mustered to meet the surge did not come close to the 30,000 beds that had been made available for Covid patients more than a year earlier, in March-May 2020.

We have seen these figures before. Last year, on December 24, the mayor had reported that the city was recording “about 2,000 hospitalizations per day.” Despite the increase in hospitalizations, Sobyanin said there were 5,000 hospital beds in reserve. He explained this was an adequate buffer and that the medical system would be able to “work calmly”.

“So far, the city’s health care system is doing well,” read a statement issued by the mayor’s office about the surge in hospitalizations. A week prior, on December 16, there had been about 12,000 Muscovites hospitalized with the virus.

So with a 5,000-bed reserve that was declared sufficient six months earlier, a daily hospitalization influx previously deemed manageable, and Moscow having been able to produce as many as 30,000 Covid-dedicated beds more than a year ago, can the current situation truly be considered unprecedented? The answer to this question is obviously yes.

All of the above data was mined from press releases and statements made to the media — because you cannot find an official, up-to-date hospital bed tally on Russia’s official Covid dashboard, nor on any other government-run website.

It’s true that millions of people are being asked to make personal sacrifices to protect hospital resources. But do they really deserve access to regularly updated figures showing how many beds have been reserved for Covid patients, and what percentage of them are currently occupied? Should Muscovites be entitled to all relevant information on this subject, so that they can examine this apparently life-altering data at any time of their choosing? That seems like an excessive and arbitrary request unless you are seriously suggesting health authorities and politicians are somehow not infallible.

Indeed, Muscovites can rest easy knowing that policies dictating the most serious matters of life are not in any way reliant upon mystical-like devotion to closely-guarded statistics.

Slightly off-topic, but we once met a man on a train to St. Petersburg who belonged to a heretical sect of the Rosicrucian Order that believed the universe revolves around the number of available bananas in Bangkok, Thailand. He patiently explained to us that everything he did was directed towards ensuring there was an adequate supply of elongated, yellow fruit in the city. But when we pressed our acquaintance to disclose how many Bangkok bananas were uneaten at the present moment, he admitted that he did not know the number — only the Thai Grocers Association had this information, and it was only dispensed periodically in small, hard-to-contextualize morsels. We later learned he was a lunatic who had escaped from a nearby psychiatric ward.

QR codes: They just make sense

By mid-June, Moscow was seeing for the first time levels of Covid hospitalizations that had not been seen since late December. Just as everything seemed hopeless, Sobyanin swooped in with a solution that was “complex, unpopular, but necessary to keep people alive”: the unvaccinated “accomplices of the epidemiological process,” as he referred to them, would henceforth be barred from dining-in unless they could cough up a PCR or antibodies test.

These walking biohazards could still go ride the standing-room-only suburban trains and pack into metro cattle cars by their millions. But sitting down for a meal would be a big no-no. This is the premise that guided the rollout of these city-saving health passes.

On July 16, Sobyanin abruptly announced that these “life-saving” passes were no longer necessary: Hospitalizations were on the decline and suddenly the city’s healthcare system was safe from implosion. He even revealed that 6,000 empty hospital beds could be reallocated to non-Covid patients.

All the Muscovites who were in desperate need of QR-coded life-preservation 3 weeks ago have now been saved.

Of course, it’s possible that there are other reasons why the QR codes are no longer deemed necessary. According to Moscow’s small business ombudsman, the digital health IDs massacred the city’s restaurants. She explained this unexpected side effect to Sobyanin as he was deliberating whether or not to keep using the life-giving passes:

We talked about the fact that almost 200 restaurants have closed in the last two weeks, and 220 in the entire last pandemic year. In two and a half weeks, we lost almost as many establishments as in the entire previous year, which was the hardest for the industry.”

Sounds like a thundering triumph for public health and overall societal well being.

No price is too high for public health

It’s undeniable that Moscow is marching towards a bright and very healthy future. But one lingering question remains: Are we certain that enough resources and civilization-bending measures are being deployed in order to guarantee that every Russian is vaccinated? After all, you cannot put a ruble-denominated price on public health.

Unfortunately, we continue to see anti-vaccine sedition posing as alleged concern for “other” public health issues that purportedly exist in Russia. For example, some might cynically propagate the fantasy that money going towards vaccines could be better spent on upgrading the healthcare system’s infrastructure. A Russian government audit published last year found that a surprising number of medical facilities across the country were without running water or central heating.

With compulsory vaccine regimes now instituted in regions across the country, it’s possible that some Russians who are being instructed to get vaccinated in order to safeguard the healthcare system live in areas where the local clinic has no running water.

This is a real nuisance because now anti-vax radicals might argue that probably a health clinic should have 20th-century infrastructure before people should be expected to take an experimental medication in order to protect it.

Then again, maybe they have a point.

Riley Waggaman is the Moscow Correspondent at anti-empire.com

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from OffGuardian can be found here ***