What drives belief in conspiracy theories, a lack of religion or too much?

AMERICANS WHO believe in the conspiracy theories collectively packaged as “QAnon” have grown quiet in recent months. They gained international notoriety after a large group of believers were among those who stormed the US Capitol building during a violent riot on January 6th. But the precise cause of the movement’s appeal has yet to be pinned down.

One prominent theory is that Americans who have no religious affiliation find themselves attracted to other causes, such as the Q craze. Another, posited by Ben Sasse, a Republican senator from Nebraska, is that modern strains of Christian evangelicalism which “run on dopey apocalypse-mongering” do not entirely satisfy all worshippers—and so they go on to find community and salvation in other groups, such as QAnon.

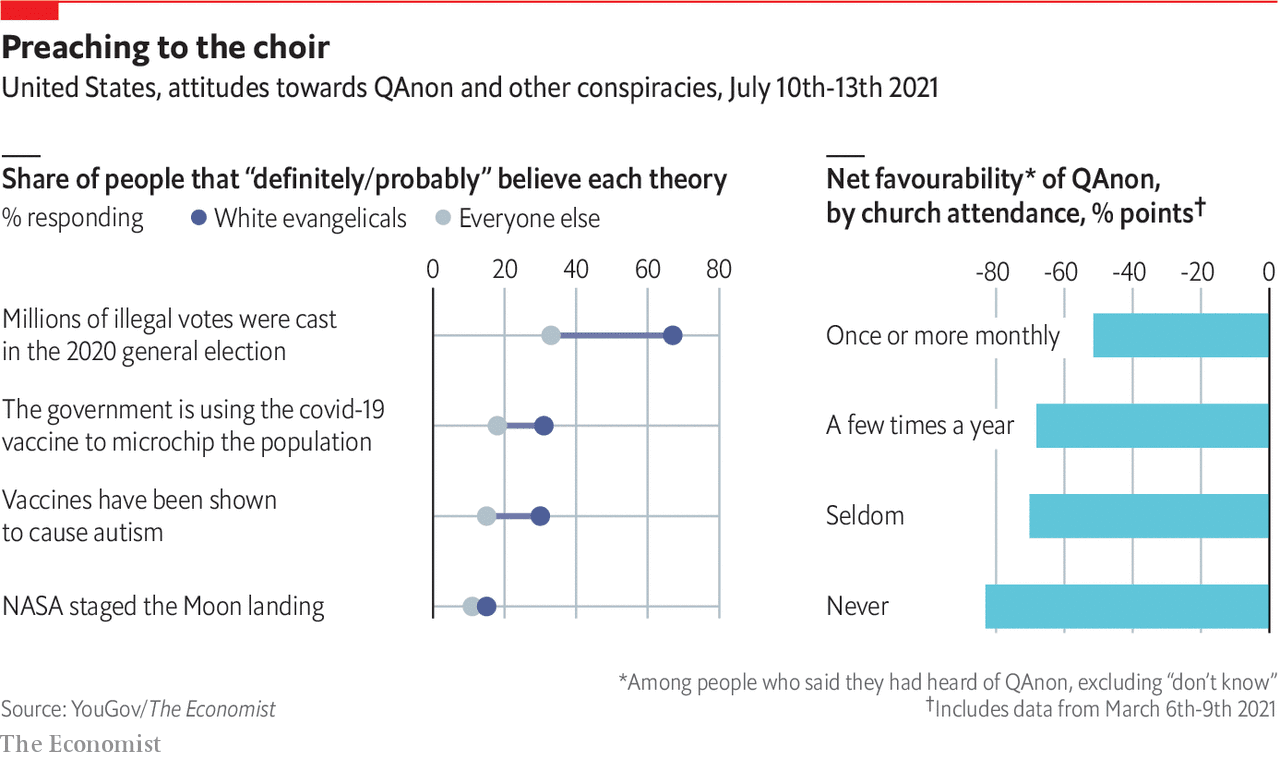

Using The Economist’s polling with YouGov, an online pollster, we can test both of these theories. From July 10th to July 13th 2021, YouGov asked Americans their racial and religious affiliations, whether they thought of QAnon favourably or unfavourably and whether they believed in a variety of popular conspiracy theories. Those theories included old stand-bys, such as whether the Moon landing in 1969 was faked.

According to YouGov’s recent polling, which we combined with an earlier survey from March to obtain a larger sample size, Americans who attend church the least are also the least likely to have a favourable view of QAnon. Among those who say they “never” go to church, just 9% who have heard of the QAnon conspiracy view it favourably. Fully 92% of these respondents view it unfavourably—a net favourability of minus 83 percentage points. But the rating among people who attend church the most—once a month or more—is minus 52 points.

We ran a statistical model to control for potential links between attitudes towards QAnon and other demographics—such as race, age, gender, education, party affiliation and vote choice in 2020. Our model confirmed that the relationship between church attendance and QAnon was not a statistical fluke: adults who attended church at least once a month were eight percentage points more likely than we predicted to rate QAnon favourably.

White evangelicals, the most religiously devout group among those surveyed by YouGov, are particularly susceptible to supporting QAnon and believing other conspiracy theories. They also tend to attend church frequently. Twenty-two percent of evangelicals who know about QAnon view it favourably, according to YouGov’s numbers—compared with 11% among the rest of the adult population. At the other end of the spectrum, 24% of evangelicals rate QAnon as “very unfavourable”, compared with 58% among other people.

But it is not clear whether those who have a favourable opinion of QAnon do so because they want membership of a social group, as Mr Sasse and others claim, or because they are merely more susceptible to conspiratorial thinking. For example, 31% of white evangelicals also believe a falsehood making the rounds on social media that the American government is using the covid-19 vaccine to microchip Americans, versus 18% among everyone else. About 30% of the group believes that vaccines cause autism, double the share among the rest of the adult population.

Belief in these theories is also linked to a person’s political views. White evangelicals are 34 percentage points more likely than other Americans to believe that “millions of illegal votes” were cast in the 2020 election. These adults also tend to be more conservative, and vote for Republican politicians more often, than non-whites and members of other religious groups do. Evangelicals are influenced by the official party line on issues of the day—even if they are conspiratorial. And adoption of one wild theory, perhaps made more persuasive by a politician’s avowals, tends to lead to the adoption of others. Beliefs are also bolstered if held by friendship groups. YouGov’s polling suggests that conspiratorial thinking does not relate to a dearth of religious fervour. On average, more devout Christians tend to be more credulous when it comes to conspiracies.