Portland’s ‘wild man’ conspiracy theorist attracted extremists in 1990s, created popular ‘Secret Government S

“You’re crazy, Ace.”

Ace R. Hayes heard this refrain time and again. He leaned into it.

The southern Oregon native launched a “Secret Government Seminar” at a storefront in Southeast Portland. He gave lectures every other Wednesday throughout much of the 1980s and ’90s, talking deep into the night about CIA dirty tricks and state corruption.

You could say that Hayes, who died in 1998 at age 58, was ahead of his time. He would have thrived amid today’s endless internet-fueled conspiracy theories about supposed “Deep State” misdeeds.

But, of course, such paranoid thinking long predates the World Wide Web.

In the late 1950s, the John Birch Society exploded in popularity thanks to its claim that President Dwight Eisenhower was a secret Communist agent. In the years that followed, millions of Americans came to believe that Lyndon Johnson, as vice president, orchestrated the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

That’s where Hayes picked up the thread.

In the late 1960s, while a student at Portland State College, the former logger and U.S. Navy vet argued that Americans could take back their government only if blood flowed in the streets.

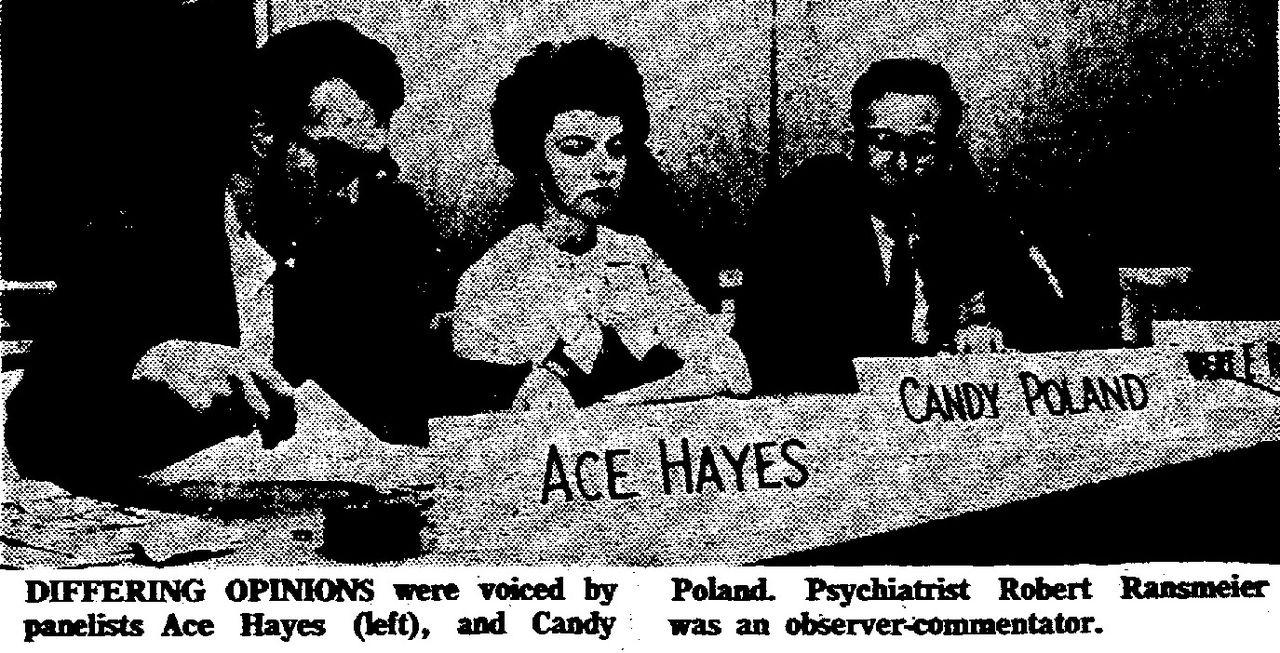

“You have to use violence,” he said at a 1967 panel discussion on “Youth Today” held at the Portland Hilton. “That means there are people in this room who will be killing each other shortly.”

He decided against joining the Communist Party, he would joke, “because they were too conservative.”

In 1967, Ace Hayes’ fiery rhetoric at an event held at the Portland Hilton shocked people and led to press coverage. (The Oregonian)

Even many of his fellow student leftists thought he was too much.

Hayes was “a wild man who all of us in the PSU protest movement dreaded seeing come around to our meetings,” said Doug Weiskopf, a leader of the 1970 “Student Strike” at Portland State. “I came in contact with him when I went to my first [Students for a Democratic Society] meeting in late 1968, and he kept insisting we do something violent to make our presence known. I was relieved when everybody pretty much ignored him.”

In the 1970s, Hayes did apparently turn to violence, or at least facilitating violence. He went to Nicaragua to help the Sandinista rebels overthrow the repressive Somoza regime.

“He said he drove down there and brought a few rifles — his little contribution to the cause,” said Per Fagereng, who owned the Portland building where Hayes held his Government Secrets Seminar.

Former Oregonian columnist Phil Stanford heard the same stories from Hayes.

“I remember him telling me he got stopped someplace [in Central America] and was prepared for a shootout,” he said. “I believe him. Ace was a salt-of-the-earth kind of guy, but he was a tough boy.”

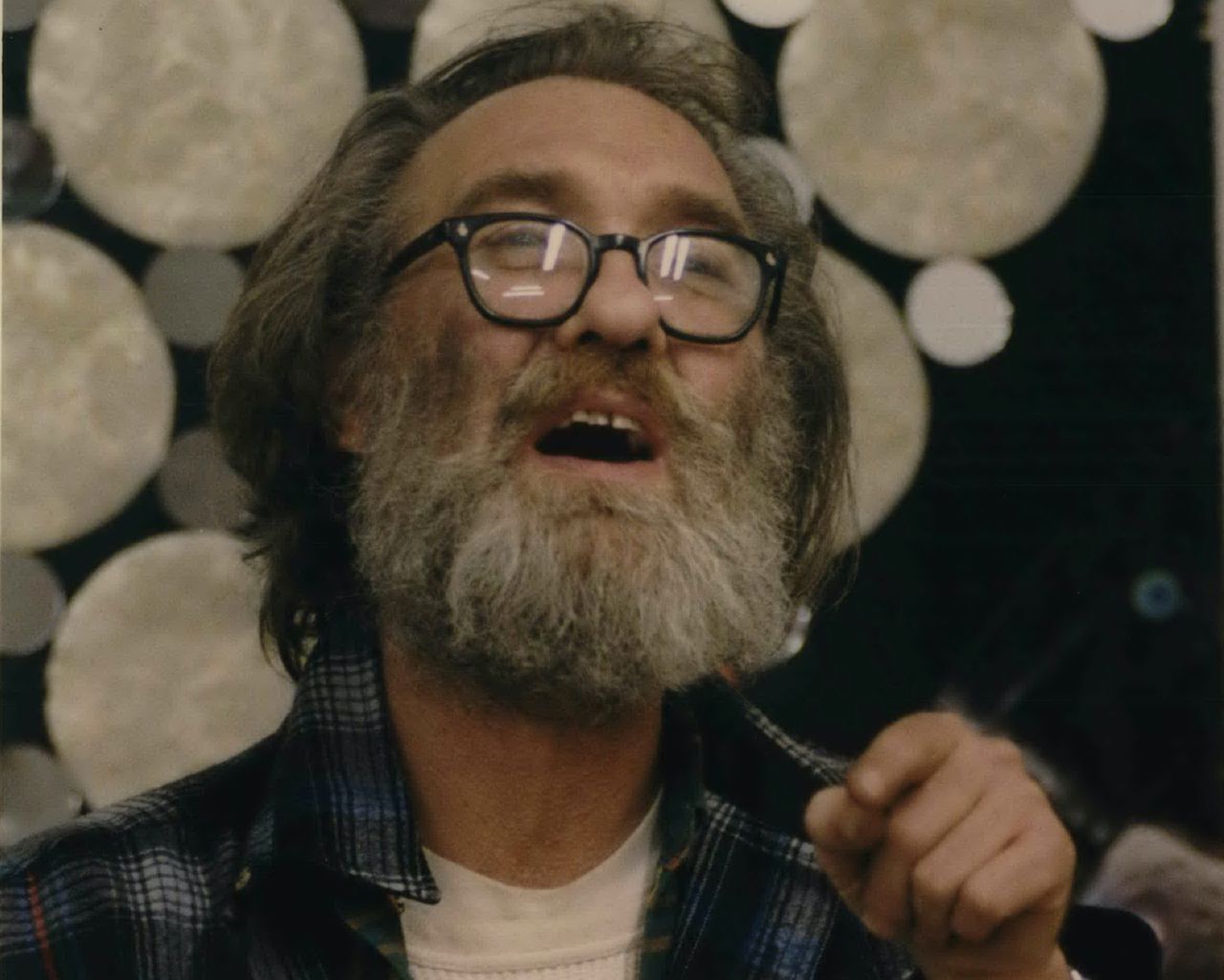

Ace Hayes believed the CIA was involved in various nefarious activities, including the drug trade in the U.S. (Mark Wilson/Getty Images/TNS)TNS

By the 1980s, still a few years before the advent of the Web, Hayes had embraced deep research as an outlet for his political rage. He bought a computer — and then purchased a subscription database called NameBase that catalogued, among other aspects of what Hayes called the “secret state,” the names and activities of intelligence agents and espionage operations.

NameBase’s founder, Daniel Brandt, became a fan — and later a friend. Musing on how best to describe Hayes, Brandt wrote in a remembrance:

“Yes, ‘colorful’ and ‘unforgettable’ are words that come instantly to mind, but ‘committed’ is more important, and ‘permanent state of indignation’ is best of all. Ace Hayes was a whirlwind, and his moral outrage could suck you in.”

With NameBase now at his fingertips, Hayes became Portland’s anti-government oracle. He began headlining at Phantom Gallery, Fagereng’s makeshift gathering spot on Southeast Belmont Street.

Hayes sat in a creaky old metal chair in the back of the space, his long hair bouncing as he made an emphatic point, the only kind of point he ever made. He always brought with him a selection of obscure books, the pages dog-eared, passages underlined, the margins filled with scrawled notes and exclamation points.

And month after month the rows of chairs facing him filled up.

[embedded content]

His popularity soon reached well beyond the bounds of the Phantom Gallery. Hayes’ lectures appeared on local cable-access TV — and his message went out via the U.S. Postal Service to followers on an ever-growing mailing list.

“So many people would come to him for his analysis of what was going on in the world,” his wife Janet Marcley said shortly after his death.

Stanford was one of the people who called Hayes crazy. He wrote it in The Oregonian, more than once.

But the columnist didn’t really believe it. He teased Hayes — he said in one column that the Portland State graduate read “too many of those far-out radical publications” — but he did so with a wink and a nod.

“More often than not I agreed with him, but, working for a big corporation, I couldn’t say it,” Stanford said in a recent interview with The Oregonian/OregonLive. “I used him as a front — and he knew it.”

This approach allowed Stanford to pepper his column with some of the darkest, most convoluted theories out there on subjects like the Iran-Contra scandal and law enforcement’s war on drugs.

Ace Hayes in 1992. (The Oregonian)Oregonian

In Hayes’ telling, the villain in these tales was always, inevitably, the U.S. government.

He claimed the state was behind various bombings and airline crashes, as well as the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

The CIA, he said, had “turned the big lie into a retail commodity that you can pick up at your local Kmart.”

Hayes, a machinist by trade, claimed at one 1991 seminar that the country’s mightiest denizens were undertaking a coordinated program to ensure that most people in the country “were fighting each other for simple survival.”

Why would the richest and most powerful Americans do that to their fellow citizens?

It was about squelching dissent, which ultimately meant squelching democracy, Hayes said.

“How do you get people to want the tanks in North Portland?” he asked his audience that night. “Well, you have enough crack houses, enough drive-by shootings. And I’m still, at this point, convinced that some of those drive-by shootings are done by people who usually pack a badge.”

He paused, let that sink in, and then reiterated it:

“A badge.”

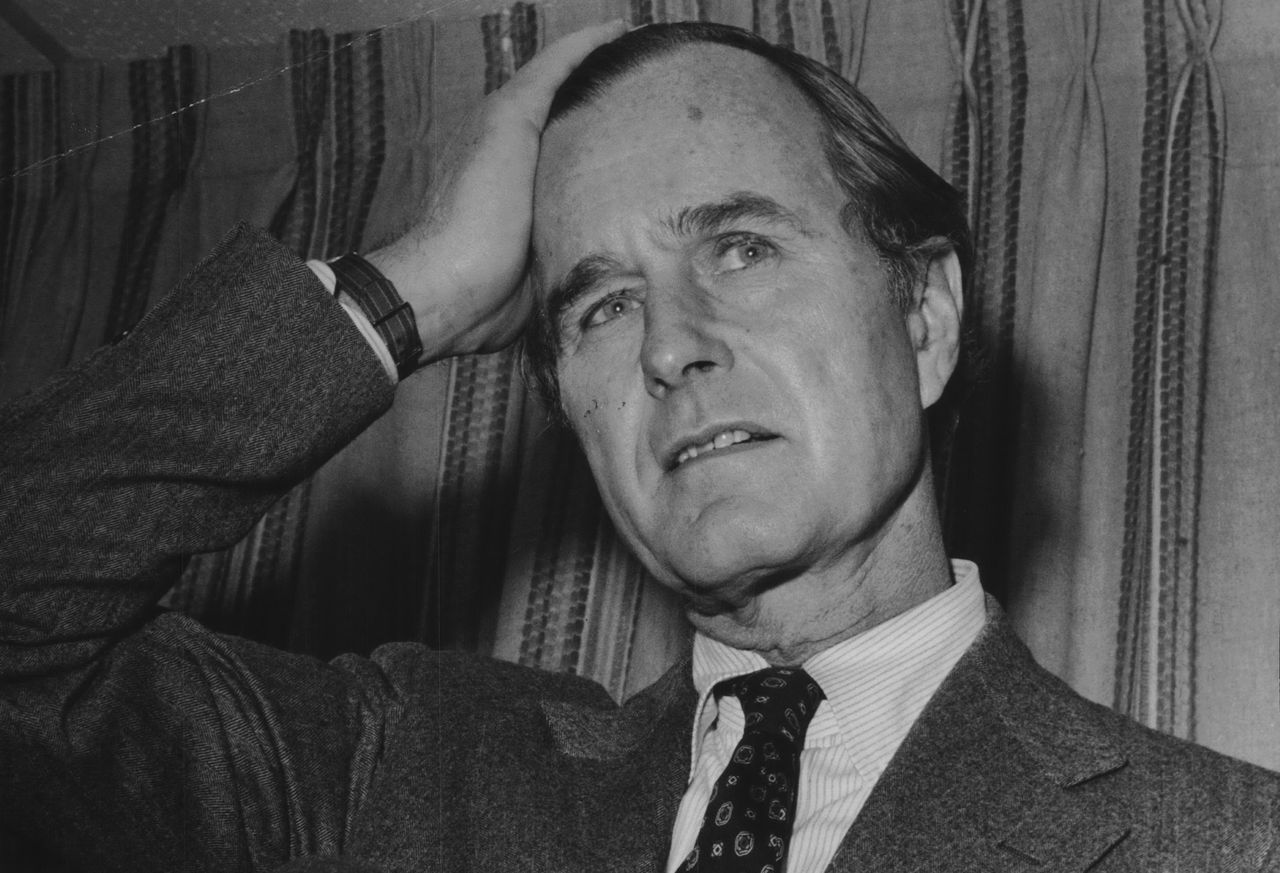

Ace Hayes believed that President George H. W. Bush, pictured here, would be forced to resign from office before the 1992 election. (Advance Local)Press-Register

Hayes believed that the only people in the U.S. more powerful than the political elite, who controlled the badge-wearing drive-by shooters, were the corporate elite, who controlled the politicians. In the summer of 1992, he was certain that billionaire businessman-turned-candidate H. Ross Perot had suddenly dropped out of the presidential race because he’d made a deal with the Bush Administration.

Here’s what was really going on, he told his followers:

News of President George H.W. Bush’s long-time corruption was about to break into the open, thanks to Perot. To keep these damning secrets under wraps, Bush would force Vice President Dan Quayle to resign and then appoint Perot to replace him. Then Bush would resign, ostensibly for health reasons, making Perot president.

None of that happened, of course.

“Ace was way off there,” Stanford admitted.

That doesn’t mean Hayes was wrong about everything. Some of the strangest early theories about Iran-Contra eventually turned out to be pretty spot-on. (The twisty 1980s scandal involved Reagan Administration officials secretly selling weapons to an international pariah, Iran, as part of an effort to secretly arm, against Congressional mandate, the anti-Sandinista rebels in Nicaragua.)

The Iran-Contra scandal dominated the political scene in the late 1980s. (Advance Local)Syracuse Post-Standard

But even if Hayes and his fellow conspiracy theorists scored the occasional home run, critics worried about where this kind of paranoid thinking was leading: namely, to the obliteration of trust in core democratic institutions — and the embrace of ever more bizarre notions about government perfidy, potentially leading conspiracy believers to violence.

Back in the early 1990s, Portland’s Coalition for Human Dignity warned that Hayes’ engaging presentation was helping extremists on the left and right find common cause in violent anti-government rhetoric. The coalition was right.

Members of the right-wing, white-nationalist group Christian Patriots started showing up at Hayes’ seminar, prompting some of Phantom Gallery’s old-hippie regulars to pull Fagereng aside and tell him it was time to finally put a stop to the lectures.

“A lot of people didn’t like Ace,” Fagereng said. “He was not your usual, college-educated left-winger. He was a country boy. He had country ideas. One of the reasons they didn’t like him is he was all in favor of gun rights.”

Hayes, who was raised in a working-class home in a small mill town, liked to point out that he wasn’t born a cynic. He said he used to be a true idealist — when he was 14 years old.

That was when he stood up at a public forum in his native Oakridge and asked Senate candidate Richard L. Neuberger if Wisconsin Sen. Joe McCarthy, famous across the land thanks to his fevered, unproven claims about communist infiltration of the U.S. government, should be censured by his colleagues.

“He didn’t give me three paragraphs of ambiguous babble,” Hayes recalled years later. “He simply said, ‘Yes, next question,’ and then, when elected, acted on this promise. I came to expect honesty from my elected officials.”

This high-minded expectation didn’t survive adolescence. By the time he was a college student in the mid-1960s, Hayes had concluded that politicians, as a rule, defaulted to lies or dissembling. American democracy, he decided, was a sham.

But his disillusionment didn’t cause him to withdraw from the arena. To the end of his days — Hayes died unexpectedly, of a brain aneurysm — politics remained his passion. And he indulged that passion through a constant stream of activities, including the alternative newspaper the Portland Free Press, which he edited. The newspaper claimed to be “read and quoted by the CIA, among others [in the power structure] — not, of course, with any great pleasure.”

Did Hayes really believe the Central Intelligence Agency kept an eye on him and his work? Who knows?

But his followers wanted to believe it. They still do.

Opined one commenter on Reddit a few years ago:

“If Ace Hayes were still alive, they’d have killed him by now.”

— Douglas Perry