How COVID-19’s origins were obscured, by the East and the West

A bus carrying a team of experts from the World Health Organization departs an airport in Wuhan on Jan. 14, 2021, after arriving in the Chinese city to investigate the origins of the coronavirus pandemic. That investigation is widely seen as having been obstructed by Chinese authorities. (Photo by Kyodo News via Getty Images)

Some 20 months after the Covid-19 pandemic first broke out, its origins remain obscure. A vigorous campaign of concealment by the Chinese authorities is the principal reason. But China received considerable help, strange to say, from senior medical research officials in the United Kingdom and United States who mishandled and effectively derailed the initial inquiry into the virus’s origins.

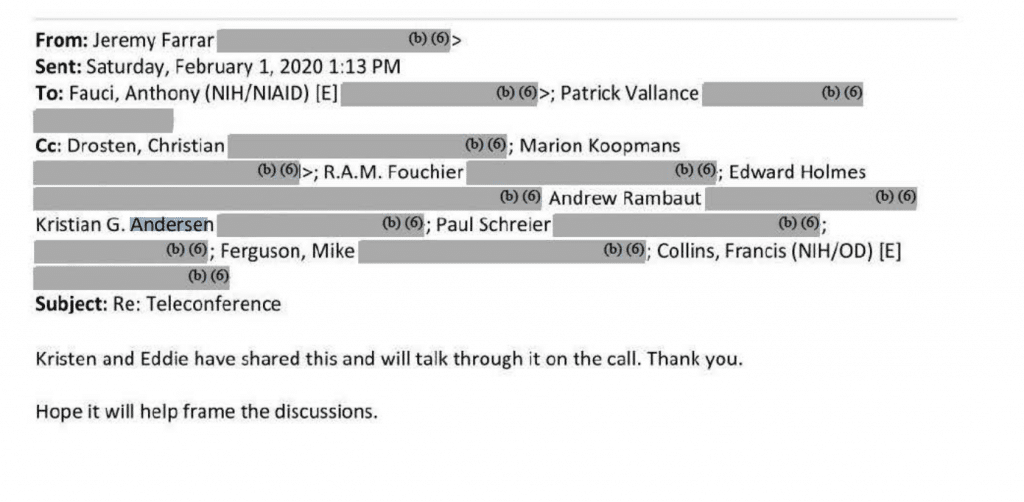

The mishandling began at a pivotal teleconference held on February 1, 2020. The organizer was Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, a large medical research charity in London. News of the conference emerged with the release this June of emails from the office of Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Farrar supplied further information in his book Spike, published on July 22.

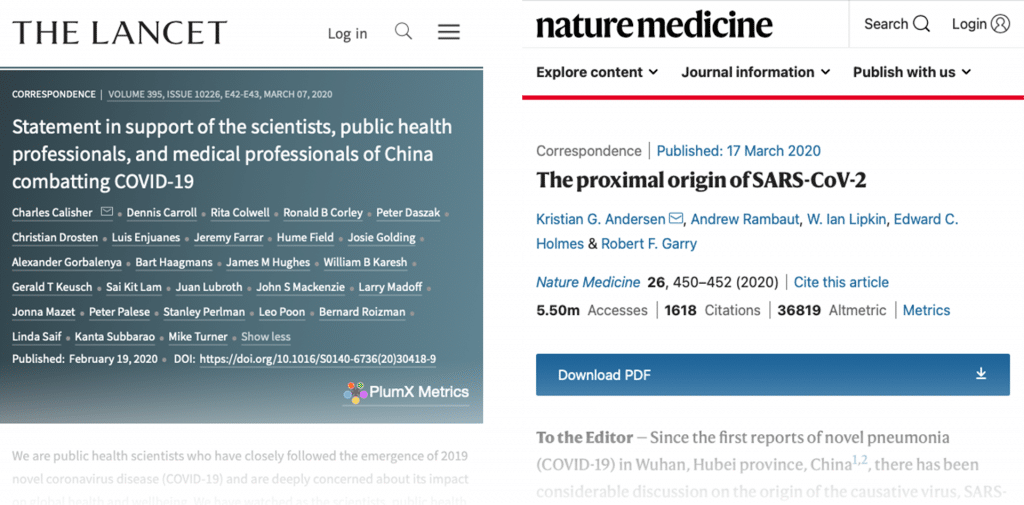

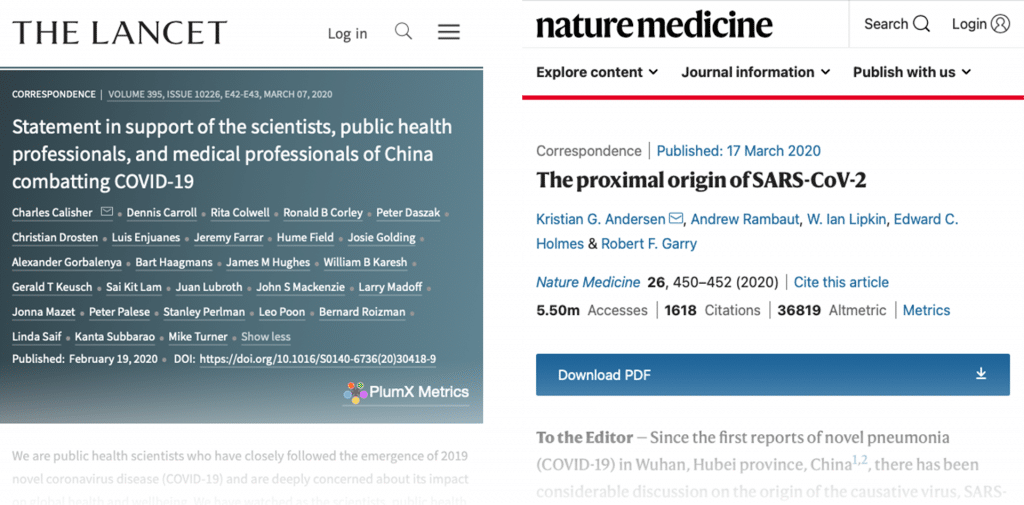

The conference was held to discuss the unanimous view of a group of virologists that the SARS2 virus had been manipulated in a lab. Yet within a few days of the meeting, the virologists abruptly reversed their conclusion. The meeting’s participants were later involved in two letters to scientific journals that stated the virus must have emerged naturally and that condemned any suggestion of manipulation as a conspiracy theory. These two letters, to The Lancet and Nature Medicine, shaped the views of the mainstream media for more than a year.

Even today, no one can say for sure whether the SARS2 virus emerged naturally or escaped from a lab. Much less could anyone have been sure back then. If the conferees had stuck to known facts, they would have left the question open to the two hypotheses, and the full exploration of the virus’s origins might not have been sidetracked for over a year.

More significant, the Chinese government would have found it much harder, if not impossible, to manipulate the World Health Organization (WHO) into setting terms of reference that favored China’s obstructive goals and kept WHO inspectors who visited China this February from accessing records vital to understanding the origin of the pandemic. China now insists those terms of reference cannot be changed, blocking further investigation into the origin of the SARS2 virus. “The two groups that produced the infamous letters in The Lancet and Nature Medicine paved the way for the Chinese government and helped enormously to facilitate all of that,” says Milton Leitenberg, an arms control expert at the University of Maryland. The reversal of the virologists’ conclusion about SARS2’s artificial origin is thus a matter of some significance.

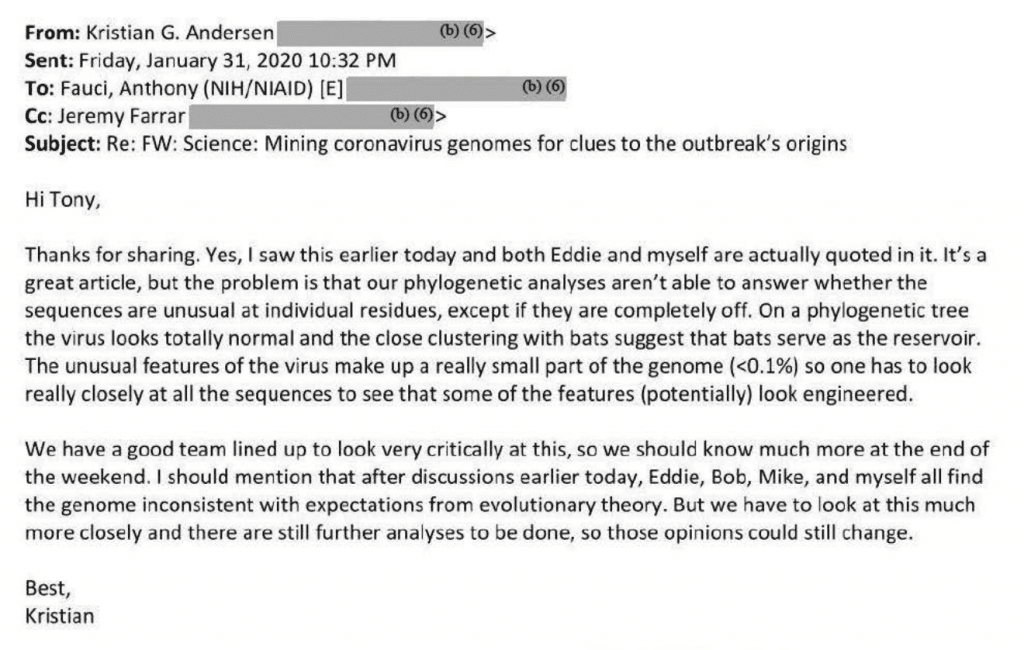

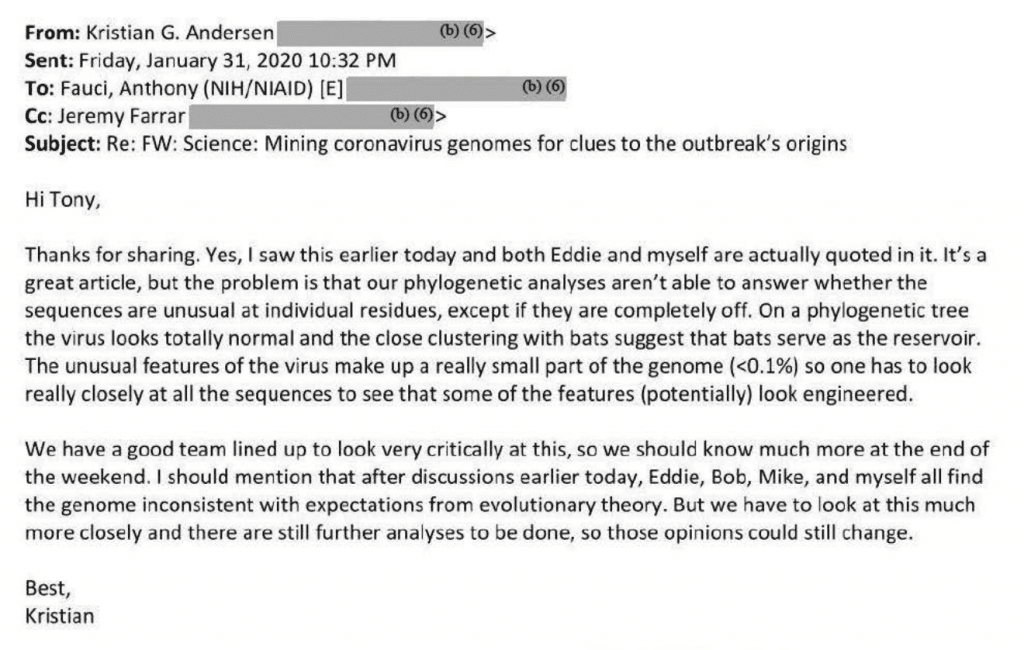

At 10:32 p.m. on the evening before the February 1 conference, Fauci had received an electrifying memo from Kristian G. Andersen, a virologist at the Scripps Research institute in California. Andersen reported that the virus seemed to be man-made. “The unusual features of the virus make up a really small part of the genome,” he wrote, referring presumably to a genetic component known as a furin cleavage site, which greatly enhances the virus’s infectivity, “so one has to look really closely at all the sequences to see that some of the features (potentially) look engineered.”

Andersen went on to note that “after discussions earlier today, Eddie, Bob, Mike and myself all find the genome inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory”— meaning that, in their unanimous view, the virus didn’t come from nature. “Those opinions could still change,” Andersen added. Eddie is Edward C. Holmes of the University of Sydney. Bob is Robert F. Garry of Tulane University. Mike is Michael Farzan at Scripps Research.

The message sent Fauci into a whirlwind of activity. “You will have tasks today that must be done,” he emailed his deputy director, Hugh Auchincloss, two hours later at 12:29 am on February 1. One of these urgent tasks evidently concerned NIAID funds that had been passed, via the EcoHealth Alliance of New York, to Zhengli Shi, China’s leading bat virus expert, at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Fauci was doubtless anxious to check whether his agency’s funding of Shi’s work had complied with US law, which banned funding gain-of-function research from 2014 to 2017 and required it be reported to a government panel thereafter. “Gain of function” refers to research in which a pathogen’s ability to cause disease is enhanced. Auchincloss replied a few hours later that efforts were underway to ascertain “if we have any distant ties to this work abroad.”

Meanwhile Farrar, who had independently heard of the Andersen team’s conclusion from Holmes, says in Spike that he arranged a teleconference set for 7 p.m. London time, convenient for both Washington and Australia, where Holmes was based.

The participants included Fauci and possibly his nominal boss, Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health. (Farrar says in Spike that Collins was present, but Collins’s name is not on the list of invitees in the Fauci emails.) Officials on the UK side were Farrar and Patrick Vallance, the chief scientific adviser to the UK government. The others were mostly virologists, including Andersen, Holmes, and Andrew Rambaut of the University of Edinburgh.

Far from being selected at random, the conferees were associated through a complicated web of relationships, a sort of virologists’ old boy network that included senior medical officials in China. Farrar was well acquainted with George Fu Gao, the head of China’s counterpart of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He has described Gao as an “old friend,” who in fact had called a month earlier, on December 31, 2019, to tell Farrar about the initial cases in Wuhan of what turned out to be Covid-19. Farrar says in his book Spike that on the weekend of the teleconference, he called another highly placed Chinese official, Chen Zhu, China’s minister of health from 2007 to 2013, to tell him of “rumours that the novel coronavirus could be the result of a lab accident.” As for Holmes, he has published many papers both with Farrar and with Gao and has been a guest professor at Gao’s CDC from 2014 until 2020.

Because of these varied connections, it seems likely that Chinese authorities knew about the conference almost from the moment it occurred and, if so, would have had the opportunity to influence deliberations that followed it.

At the conference there was a notable imbalance of power between the virologists and the officials. Fauci and Farrar together control a large portion of the funds available for virological research in the Western world. A virologist keen to continue his career would be very attentive to their wishes. Two of the conference participants had multimillion-dollar grant proposals under final review with NIAID at the time of the call.

Almost all references to what was discussed at the teleconference have been redacted from the Fauci emails under exceptions to the Freedom of Information Act. The conference would doubtless have included explanation from Andersen and Holmes as to why they had concluded the previous evening that the virus had been altered through laboratory manipulation. “Kristen and Eddie have shared this and will talk through it on the call,” Farrar writes in one of the Fauci emails.

Whatever was said at the meeting, it was followed by a remarkable and almost immediate about-face. By at most three days later, Andersen had executed a 180 degree turn in his views about the virus. In an email of February 4, 2020 to Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, which had directed NIAID funds to Shi, Andersen wrote, “The main crackpot theories going around at the moment relate to this virus being somehow engineered with intent and that is demonstrably not the case.” The email was obtained by U.S. Right to Know, an investigatory group.

Participants have not explained what was said at the meeting or found in the days immediately following it to induce the change of mind. Media offices at the Wellcome Trust and NIAID declined to comment on this article. Andersen, Holmes and Rambaut did not reply to emails seeking an account of the reversal.

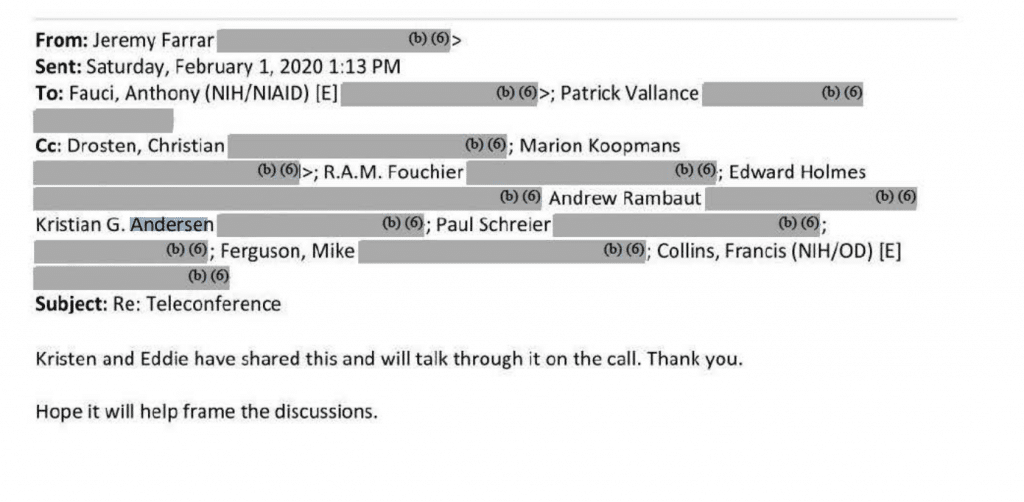

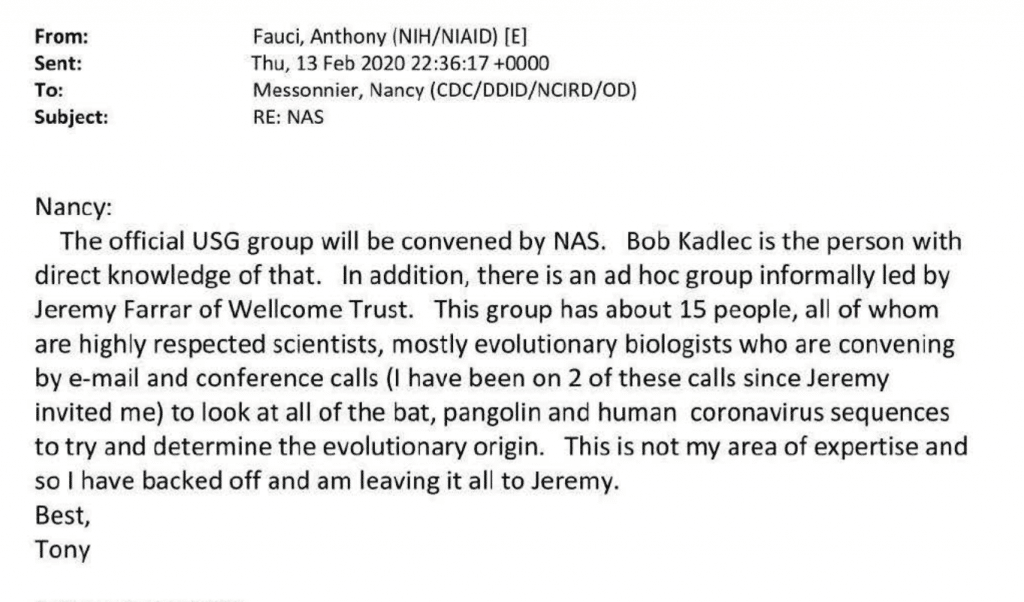

Farrar, not Fauci, seems to have been the leader in the teleconference’s deliberations. “This is not my area of expertise so I have backed off and am leaving it all to Jeremy,” Fauci wrote on February 13 to a CDC official. US officials were not to take the lead in this pivotal inquiry.

Farrar had a direct hand in the two letters that went out to the Lancet and Nature Medicine. He was a signatory of the Lancet letter, a draft of which Daszak, the organizer of the letter, began circulating just five days after the conference. The letter sought to squelch all discussion of the possibility that the virus had escaped from a lab by deriding it as a conspiracy theory. When Daszak wrote an article in the Guardian elaborating on the same theme, Farrar promoted it with a tweet, saying “as always worth reading @PeterDaszak.”

Ignore the conspiracy theories: scientists know Covid-19 wasn’t created in a lab – as always worth reading @PeterDaszak https://t.co/Y9QzUT4tAr

— Jeremy Farrar (@JeremyFarrar) June 9, 2020

Farrar also recruited the five authors who drew up the Nature Medicine letter, his spokesman told the writer Ian Birrell. (The spokesman referred to the Lancet letter but evidently meant the Nature Medicine letter, which has five authors.) The Nature Medicine letter, accepted on March 6 and published on March 17, 2020, presented a detailed and influential case that the virus had emerged naturally from animals. Its authors were Andersen, Rambaut, W. Ian Lipkin, Holmes and Garry.

In his book Spike, Farrar portrays the events between the February 1 conference and publication of the two medical journal letters as a judicious process in which he held an agnostic view and played no role other than asking questions. “On a spectrum if 0 is nature and 100 is release—I am honestly at 50!” Farrar says he emailed to Fauci and Collins a day after the conference. But if that were honestly so, he fails to explain his switch from 50 to 0 when signing the Lancet letter a few days later.

According to Spike, it wasn’t until March, “after the addition of important new information, endless analyses, intense discussions and many sleepless nights” that Andersen and his four fellow virologists “were ready to pronounce on the origins of the novel coronavirus.” Why then was Andersen, the virologists’ leader, ready to pronounce just 3 days after the conference that lab release was a conspiracy theory? Farrar’s account does not match with the available facts.

Nor does Andersen’s. In a June interview with the New York Times, he painted a picture that includes a change of mind on the possible engineering of the virus “in a matter of days, while we worked around the clock,” and then that quick reversal being buttressed by drawn-out research.

“This is a textbook example of the scientific method, where a preliminary hypothesis is rejected in favor of a competing hypothesis as more data become available and analyses are completed,” he said in a statement released by Scripps Research after his Jan 31 email to Fauci had become public. “I cautioned in that same email that we would need to look at the question much more closely and that our opinions could change within a few days based on new data and analyses—which they did,” Anderson said in the New York Times interview. In that same interview, he also said that “more extensive analyses, significant additional data and thorough investigations to compare genomic diversity more broadly across coronaviruses led to the peer-reviewed study published in Nature Medicine.”

These later data and analyses would not have been available three days after the conference, the date of Andersen’s volte-face email to Daszak. And they would not have been available to Farrar as he signed the Lancet letter, which was published just 17 days after the teleconference.

More puzzling is Andersen’s statement that in his preliminary studies “the genome of RaTG13, a SARS-related coronavirus found in bats, wasn’t yet available.” In fact its full sequence had been deposited by Shi in a data bank on January 24, 2020, a week before Andersen’s report to Fauci, and Farrar says in Spike that he had seen the sequence by the time of the conference. RaTG13 is the closest known relative of SARS2, and the fact that it lacks the furin cleavage site found in SARS2 would have been a major reason for the Andersen group to suppose that this genetic element had been inserted into SARS2 in a lab.

Given his role in leading the February 1 teleconference, in presiding over the virologists’ 180 degree change of views, and in arranging or influencing the Lancet and Nature Medicine letters, Farrar was evidently the driving force of the campaign to persuade the public that the SARS2 virus could not possibly have leaked from a lab. This was an unfortunate position for any scientist to take, given that he was assuring the public of something he could not be sure was true.

Farrar now says in Spike that, although natural emergence is more likely, “nobody is yet in a position to rule out an alternative.” But his campaign sought very vigorously to do exactly that. “We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin,” Farrar and his cosignatories wrote in the Lancet on February 18, 2020. This lapse in scientific judgment reflects also on the other senior participants in the conference who saw what was happening but apparently took no steps to insist that scientific truth should take precedence over unjustifiable professions of certainty.

The decision to quash any notion of lab escape seems to have brought relief all round. At least until the tide of opinion began to change a year later, Fauci and Collins didn’t have to endure unpleasant questions about why they had been funding hazardous research in minimally safe conditions at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

“I just wanted to say a personal thank you on behalf of our staff and collaborators, for publicly standing up and stating that the scientific evidence supports a natural origin for COVID-19 from a bat-to-human spillover, not a lab release from the Wuhan Institute of Virology,” Daszak emailed Fauci after a White House press briefing on April 17.

#EHAevent #ZikaVirus presentation from the incomparable Dr. Anthony Fauci @NIAIDNews pictured with Dr. Peter Daszak pic.twitter.com/VJJsmwZ5aU

— EcoHealth Alliance (@EcoHealthNYC) March 31, 2016

In August 2020 the NIAID announced it would award $82 million over five years to 10 participants in its new network for detecting infectious diseases. Among the lucky winners: Daszak, Andersen, and his associate Robert Garry.

The perturbing lab leak theory raised by Andersen and his colleagues on January 31, 2020 had been safely laid to rest. Farrar and his colleagues had succeeded in the one goal also pursued by the autocrats in Beijing, that of suppressing discussion of whether the SARS2 virus might have escaped from the Wuhan lab.

Beijing’s way of squelching inquiry about the virus was, unintentionally, somewhat more obvious than the methods used in London. Chinese authorities tried so hard to stamp out information about the virus’s origin that they left a rather clumsy trail of footprints pointing to where they didn’t want people to go.

One of the more informative suppressions of data was the closure of China’s main database on bat and other viruses. Zhengli Shi, China’s leading expert on bat coronaviruses, told the BBC that it was taken off line because of numerous hacking attempts. It’s conceivable that in January 2020, after the pandemic broke out, people without authorized access might have tried to hack into the database. But in fact the database went off line on September 12, 2019. Who would have wanted to hack into a bat virus database back then? More likely, that is the date at which Chinese authorities realized they had a virus escape problem.

In February of last year, President Xi referred to the need to ensure biosafety and biosecurity, and the Chinese Communist Party followed by tightening up their biosafety rules in October 2020, accelerating a long planned revision. “To me, the fact that the CCP enacted a major series of laboratory biosafety regulations this past year is an indication that China’s political leadership believes that a lab accident is likely to have caused the pandemic,” says a biosurveillance expert who has monitored China’s disease outbreak reporting for the past two decades.

Major clues as to what happened are evident in Shi’s various pronouncements about the virus. The omissions and untruths in these statements are specific enough to outline the very body of facts the censors have sought to conceal.

In looking at Shi’s questionable statements, it’s only fair to keep in mind that they may have been compelled. Her train of deceptions began immediately after the genetic sequence of the SARS2 virus was published on January 10, 2020, by Yong-zhen Zhang of Fudan University, against the wishes of Chinese authorities who subsequently closed his lab for a time. Where did this strange new virus come from? Shi wanted or was told to establish SARS2’s pedigree as a bat virus, with an ancestry analogous to that of SARS1, the bat virus that caused an epidemic in 2002. In an important paper published on February 3, 2020, Shi reported that the genome of SARS2 is 96 percent similar to that of a bat virus, RaTG13, “which was previously detected in [the bat species] Rhinolophus affinis from Yunnan province.”

Shi neglected to mention a salient difference between the two viruses, namely that SARS2 possessed a furin cleavage site and RaTG13 did not. Alina Chan, of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, has likened the omission to describing a unicorn by reporting all its horse-like features, but neglecting to mention the horn. Evidently the Chinese authorities were highly sensitive to the furin cleavage site’s presence.

Shi also failed to say when and where she had discovered the RaTG13 virus, surely important data for the closest known relative of SARS2. In fact, she had found RaTG13 in 2013, in an abandoned mine in Tongguan—the same place where six miners had fallen sick the year before. At that time, she analyzed just one of its genes and reported the virus under another name, BtCoV/4991. Daszak, the holder of her NIAID grant, told the London Times, perhaps on misinformation from Shi, that the virus was then thrown in a freezer and forgotten about until 2020. This was untrue—the virus was of much greater interest. Shi had analyzed its full genome, probably by 2018, but did not publish it. It was only when she needed a bat virus pedigree for SARS2 that Shi released information about the virus, which she now renamed RaTG13.

The likelihood that BtCoV/4991 and RaTG13 were one and the same – later confirmed by Shi – was first suggested by Rossana Segreto of the University of Innsbruck; Monali Rahalkar and Rahul Bahulikar, two internet-sleuthing researchers in Pune, India, established that the unprovenanced RaTG13 had been found in the same mine where the miners died.[1]

It’s not acceptable practice among scientists to report something already published under a different name as if were new. Shi’s February paper had the goal of portraying SARS2 as just another bat virus while concealing the true provenance of its closest known relative—a cave known to harbor lethal viruses.

When RaTG13’s connection to the Tongguan mine was pointed out, Shi still tried to conceal the lethality of the mine’s bat viruses, saying the miners had died of a fungus infection. This untruth was corrected when a master’s thesis by a Chinese doctor, Li Xu, was unearthed by the internet sleuth who calls himself TheSeeker268. The thesis reported that the miners had died of a SARS-related virus with symptoms identical to those of Covid-19 and with CT scans similar to those of Covid patients. The only evident difference between that virus’s effects and those of SARS2 is that the miners’ virus was not readily transmissible from one person to another.

The specificity of what Shi’s statements concealed—the furin cleavage site, RaTG13’s identity with BatCoV/4991, the latter’s origin in the mine where six miners were infected, the death of the three miners from infection by a virus with symptoms very similar to those of SARS2—all point to the involvement of these elements in a scenario the Chinese authorities are determined to cloak. That scenario may have been the storage or generation of the SARS2 virus in Shi’s lab from one of the many viruses recovered from the Tongguan cave.

The Chinese government’s persistent stonewalling and Shi’s pattern of evasions do not amount to proof that the SARS2 virus escaped from her lab. But they seem less like the actions of innocent people and more like attempts to cover up a fatal accident, one that has caused the deaths of maybe 10 million people and counting.

Perhaps proof will one day emerge that the virus emerged naturally. If not, the likelihood that SARS2 escaped from a researcher’s laboratory is an albatross that will hang round China’s neck in perpetuity. China’s only hope of release from this terrible encumbrance lies in opening its laboratory doors and either establishing its innocence or admitting its fateful error.

Notes

[1] Editor’s note: This article was updated on August 22, 2021 to correct the account of the discovery that BtCoV/4991 and RaTG13 are the same virus.