‘Center of the maelstrom’: Election officials grapple with 2020’s long shadow

Now, those officials — who in many states also manage bureaucracies around things like business registration and licensing barbers and hairdressers — find their jobs dominated by elections. They have been besieged by conspiracies about what happened last year, and they’re increasingly being targeted personally by those same misinformation campaigns.

“I can’t help to think that it undergirds everything we’re doing here,” Oregon Secretary of State Shemia Fagan, a Democrat first elected to the office last year, said of the 2020 election and its aftermath. “It has just changed the game.”

The conference also made clear that the shadow of 2020 was still hanging over their offices for the foreseeable future.

There were persistent rumors that there were, as the group’s executive director put in the closing meeting, “crazy people” who snuck into the conference and were trying to secretly film the secretaries. One longtime attendee noted that security, while not overwhelming, was significantly more visible than in years past, and uniformed police officers were a regular presence at the conference. At least one secretary had private security at the conference, and another noted that they had contacted law enforcement while in Iowa to report a new violent threat they received back home.

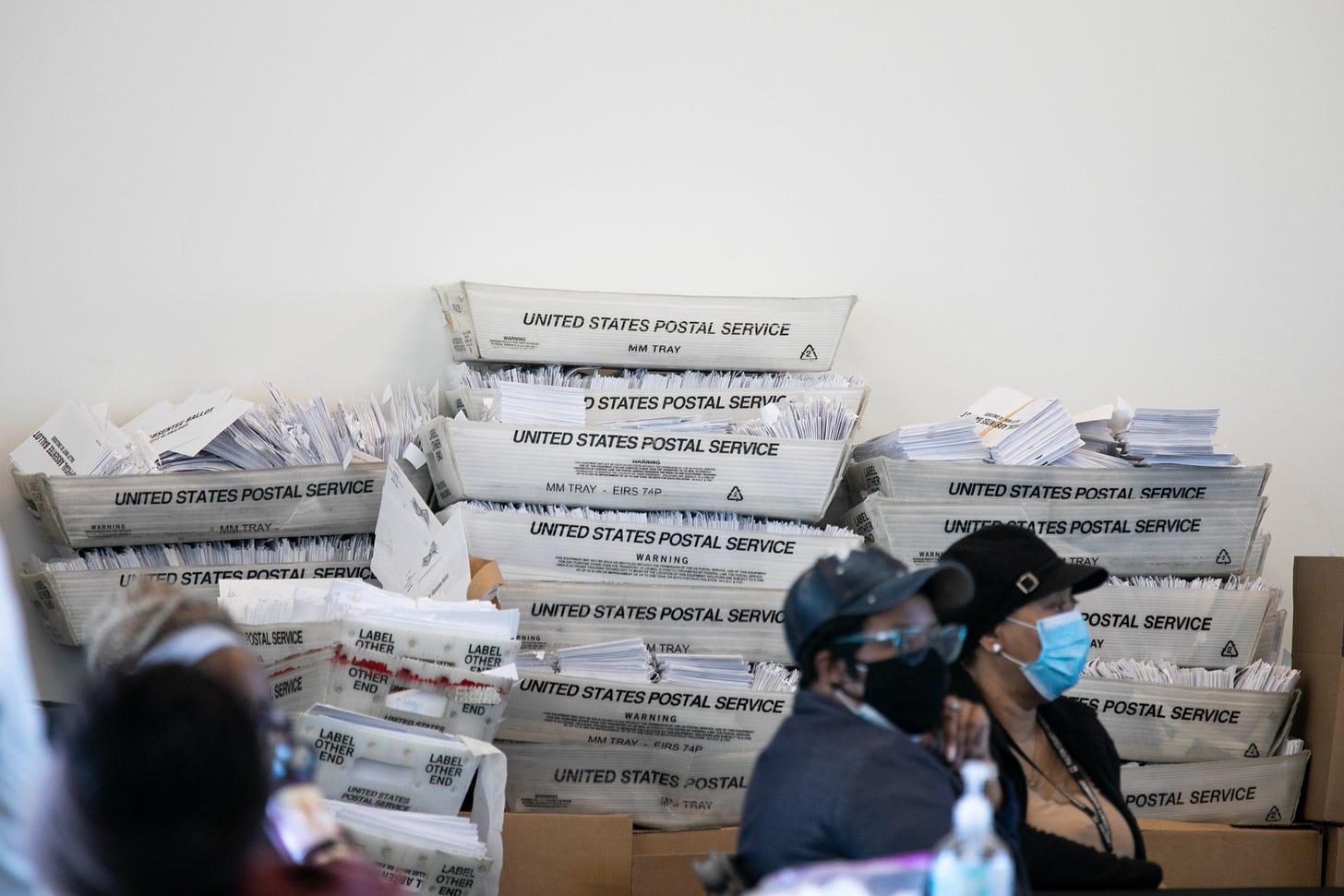

And there were constant signals that the pandemic — which led to likely-enduring changes in the way elections are conducted — is far from over: The conference space was lined with signs asking attendees to “please wear a mask,” and some secretaries opted to not attend in-person, given the risk of the Delta variant.

Battling misinformation

Secretaries say that their role as chief elections officers have become significantly more public-facing, both in the run-up to and aftermath of 2020, when former President Donald Trump rampantly misled Americans about the security and integrity of the presidential election, something he continues to do to this day.

“There’s a big shift. I think a lot of that is driven by the fact that we are so public right now. We’re in the center of the maelstrom,” said Connecticut Secretary of State Denise Merrill, a Democrat who has been in office since 2011. “That puts us right on the front page almost every day. That was never true before.”

Merrill and many of her colleagues trace the start of this trend back to 2016, when Russian disinformation campaigns and an intense focus on cybersecurity shot election officials to the top of public consciousness. That has drastically changed how they communicate with the public.

The public “didn’t get into the weeds on the technical things,” said Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate, a Republican who is serving as his state’s chief election official for a second time after holding the office in the late 1990s. “And what we’ve seen in the last two cycles, they want more,” he said. “Our messaging is probably going to be more technical,” he continued.

But, increasingly, the conspiracies and misinformation around elections are leading to false accusations — and, in some cases, physical threats — targeting these public officials. “When our office would get emails or phone calls from those with misgivings about the election system, it would mostly be about allegations of other people doing bad things,” said Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon, a Democrat. “Now, in the last couple of years, those allegations have been directed at elections administrators themselves.”

To combat it, election officials have leaned on a wider swath of community organizations to talk about election processes. Secretaries hope that by having a regular line of contact with community and faith-based groups, those groups in turn could combat misinformation among their members. “It’s not something you can just do with a slick PR campaign,” said Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat who is running for governor next year.

Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose, a Republican who co-chairs the elections committee for NASS, said he has also tried to pull more people into the elections process. Last year, his office placed a heavy emphasis on recruiting and training more poll workers than needed, up to 150 percent of what election officials would normally require. That, he said, had two benefits: Officials would be able to weather any last-minute pandemic disruptions, but it also meant that there were more people in the community who were organic disruptors of election disinformation.

“When somebody at church says, ‘Hey, did you hear about that polynomial algorithm,’ or all these wild things that somebody spreads? They can lean over and say, ‘I did the training, man. That stuff’s not true,’” LaRose said.

Election officials are also making a more concerted effort to talk to elected officeholders like state legislators, said Utah Lt. Gov. Deidre Henderson, a Republican. (Utah’s lieutenant governor is the state’s chief election officer, and she is a member of NASS.) She said she has reached out to lawmakers to invite them to tour county clerk offices, to see how the election is run.

“State legislators really are closest to the people. They’re the boots on the ground,” she said. “They can actually help perpetuate the misinformation themselves, or they can help simmer things down and provide education to their constituents.”

Henderson also acknowledges that not every state legislator will be reachable. Some “are so addicted to the outrage that’s pervasive right now,” she said. “And those are the ones to me that are fairly dangerous,” saying they are working “actively to undermine public trust in our democratic processes.”

It also means beginning to rethink how election offices are run and staffed. Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows, a Democrat and one of the newest secretaries of state in the country, said she worked to convince the legislature to add new funding to increase the size of her elections staff, which will go from 8 to 11 people. She is also pushing to create a separate election audit and security division.

For many of the secretaries, it also means broadening where they’re reaching voters, especially online. Fagan, the Oregon secretary, said she would get her office onto TikTok, the social media video platform that is immensely popular with Gen-Z Americans.

“If we’re only putting out accurate information and press releases picked up by credible news organizations, we’re missing all the people that are sharing Facebook memes about Sharpiegate,” she said, referencing a conspiracy theory that percolated on the internet shortly after the election. “We can’t combat memes and TikTok videos about voter fraud with PDFs on government websites that nobody’s going to read.”

Secretaries are also grappling with a push from Trump and his supporters to relitigate the 2020 election. At the conference, secretaries nearly universally agreed on a series of guidelines on post-election audits, in part to try to tamp down the wave of conspiracy-fueled reviews for which Trump and his supporters have pushed.

Protecting themselves

The rampant misinformation around the 2020 election has also exposed election officials to an unprecedented level of violent threats from conspiracy theorists who believe that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump. The threats have targeted everyone from the secretaries themselves to local poll workers, and is perhaps the greatest challenge facing the election administration field.

“The threats haven’t abated, and I assume that they’ll increase again as we get closer to ‘22 and ‘24,” said Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat who co-chairs the election committee alongside Ohio’s LaRose. “The anxiety level, knowing that there are people out there who wish you ill — and that’s putting that nicely — it’s hard to live in that norm.”

The threats could escalate and drive “good people” away from election administration, Benson and others worry.

The constant threats also change how secretaries go about their daily lives in big and small ways. Multiple secretaries said they had fairly constant contact with their local and state law enforcement as threats have become an almost regular part of their job. Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold, a Democrat, said that her office was getting “death threats all last week” because of “the pillow conference,” a reference to a conspiracy-laced “cyber symposium” hosted by Trump ally and MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell.

It also means they are constantly vigilant. One secretary remarked offhandedly that they didn’t think they’d use an embroidered NASS duffel bag they got at the conference, because it had their name on it, and they didn’t want to increase the odds someone recognized them while they were traveling. Another said they installed surveillance cameras at their home after Jan. 6.

Federal law enforcement has only recently started to respond to the seriousness of the threats to election workers. In June, the Justice Department said that it would be setting up a task force to prioritize investigating threats directed at election officials.

“There’s recognition that in this last election cycle, there was a greater number of election-related threats than this country has ever seen before,” John Keller, the principal deputy chief of the public integrity section of the DOJ, told conference attendees. “But also the recognition that the response has been inadequate.”

The constant stream of misinformation about the 2020 election — and the threats to secretaries that arise because of it — is also putting a strain on election administration in general, because it prevents them from entirely moving on to preparing for the next election. Many states will have local elections later this year, while still grappling with a pandemic, and a post-redistricting midterm cycle next year is expected to be especially chaotic.

“I think we’re all just kind of trying to figure out when is 2020 going to end, and when are we going to start looking forward?” asked Washington Secretary of State Kim Wyman, a Republican. “I don’t think it’s going to happen anytime soon.”