Trump-inspired conspiracies about voter fraud have infiltrated the California recall. And they may cost supporters votes

The campaign to recall California Gov. Gavin Newsom has a conspiracy theory problem, and it just might siphon off votes that could aid its cause.

In an illustration of the fallout from Donald Trump’s “Stop the Steal” lie that the 2020 presidential election was stolen from him, California recall supporters have unleashed streams of unfounded allegations on Facebook and other online forums, suggesting the state will continue in mass voter fraud to keep Newsom in power.

“We all know 2020s [sic] election was stolen from President Trump,” a woman wrote last month in a private Facebook group run by the pro-recall campaign to rally support in Orange County. “If we can’t guarantee election integrity, the Dems will cheat again.”

“We can vote all day but if it’s in a corrupt voting system it’s not going to matter!” a recall supporter from San Bernardino County wrote, also last month, in the campaign’s public Facebook group, which is statewide and has 25,000 members.

These views are anything but isolated, according to a Chronicle analysis of two months of posts and comments on the recall’s official Facebook pages. Supporters have repeatedly pushed conspiracy theories and other false or unsupported claims about next month’s election, as well as the pandemic and other issues.

On Aug. 15, for example, nearly half of the 47 posts published to the pro-recall campaign’s public Facebook group, “RecallGavin2020.com — Home Page Public Forum,” contained either overtly false claims, references to popular conspiracy theories or expressions of concern about election rigging in either the body of the post or the comments.

The intensity of these assertions — which have been amplified by the Republican front-runner in the election, radio host Larry Elder — has prompted both recall supporters and voting experts to worry they could diminish trust in the election and even discourage some people from voting altogether.

“Distress at that level can make people feel like this election — or any election — may be not worthy of their time,” said Mindy Romero, director of the Center for Inclusive Democracy. “And as we know, from the polls and lots of research that’s happened post-2020, Republicans are much more likely to believe the election was stolen, much more likely to distrust the electoral process. And I think it’s just dangerous ground. It’s not good for a democracy.”

Many recall supporters appear to be aware of the danger, pushing back in online forums, though not necessarily correcting false assertions.

In response to the San Bernardino County resident’s comment about alleged corruption, a fellow recall backer wrote, “Please vote even if you have doubts about the credibility of our system. If Newsom cheats, your vote is a fingerprint for evidence. There’s a freight train of forensic audits heading to every state. He will get caught.”

Orrin Heatlie, the organizer of the Newsom recall petition, said in interviews that he was concerned that election-related myths might decrease voter turnout. Policing disinformation, he said, has become “a never-ending chore,” but a necessary priority for the campaign, officially known as the California Patriot Coalition — Recall Governor Gavin Newsom.

“If people feel their vote won’t count, they won’t vote,” Heatlie said.

Radio talk show host and leading recall candidate Larry Elder, shown speaking during his show in Burbank, has amplified conspiracy theories about voter fraud.

Marcio Jose Sanchez/Associated Press

He said his team appointed roughly 240 volunteer administrators to moderate the campaign’s dozens of Facebook groups. In general, each county has one, some metro areas do, too, and there are a handful of statewide groups. Heatlie said these moderators are trained to take down posts that contain what they consider to be clear misinformation, including references to the QAnon conspiracy theory.

“We have strict policies regarding the content that we allow to be posted on these groups. It’s got to be related to California politics and the recall,” Heatlie said. “Sometimes a post will get through and if we find out about it, then we remove them.”

And if a particular administrator lets too many false claims fly? “Then they’re removed from the group,” he said.

But The Chronicle found many false or unfounded posts that were not removed. Heatlie said the campaign doesn’t have “the bandwidth to screen every comment,” and acknowledged that some posts by recall supporters concerned about fraud are not removed but challenged.

“Sometimes the discussion is good,” he said, “because people will point that out and the discussion that ensues helps people figure out the reality of the situation.”

Facebook, which according to Heatlie has removed some posts and comments from these groups, has Community Standards that bar the “misrepresentation of who can vote, qualifications for voting, whether a vote will be counted, and what information and/or materials must be provided in order to vote.”

Facebook relies on artificial intelligence and third-party fact-checkers to flag or remove content it determines is in violation. In a 2018 blog post, Facebook Product Manager Tessa Lyons described the limitations of this approach, saying, “Even where fact-checking organizations do exist, there aren’t enough to review all potentially false claims online. It can take hours or even days to review a single claim.”

Told of the prevalence of conspiracy theories in the groups affiliated with the recall campaign, a Facebook spokesperson said via email: “We connect people with reliable information about when and how to vote ahead of elections. We enforce our rules prohibiting voter suppression and other policies, including in private groups, using a combination of machine learning and teams of people.”

But whatever increased policing social media companies like Facebook and Twitter have done has not stopped the sharing of false information about voting by some recall supporters.

“They have their eggs in one basket because they will cheat the election,” a member of an Orange County recall group wrote on July 14. “Millions of ballots going to people who dont [sic] exist. Etc etc.”

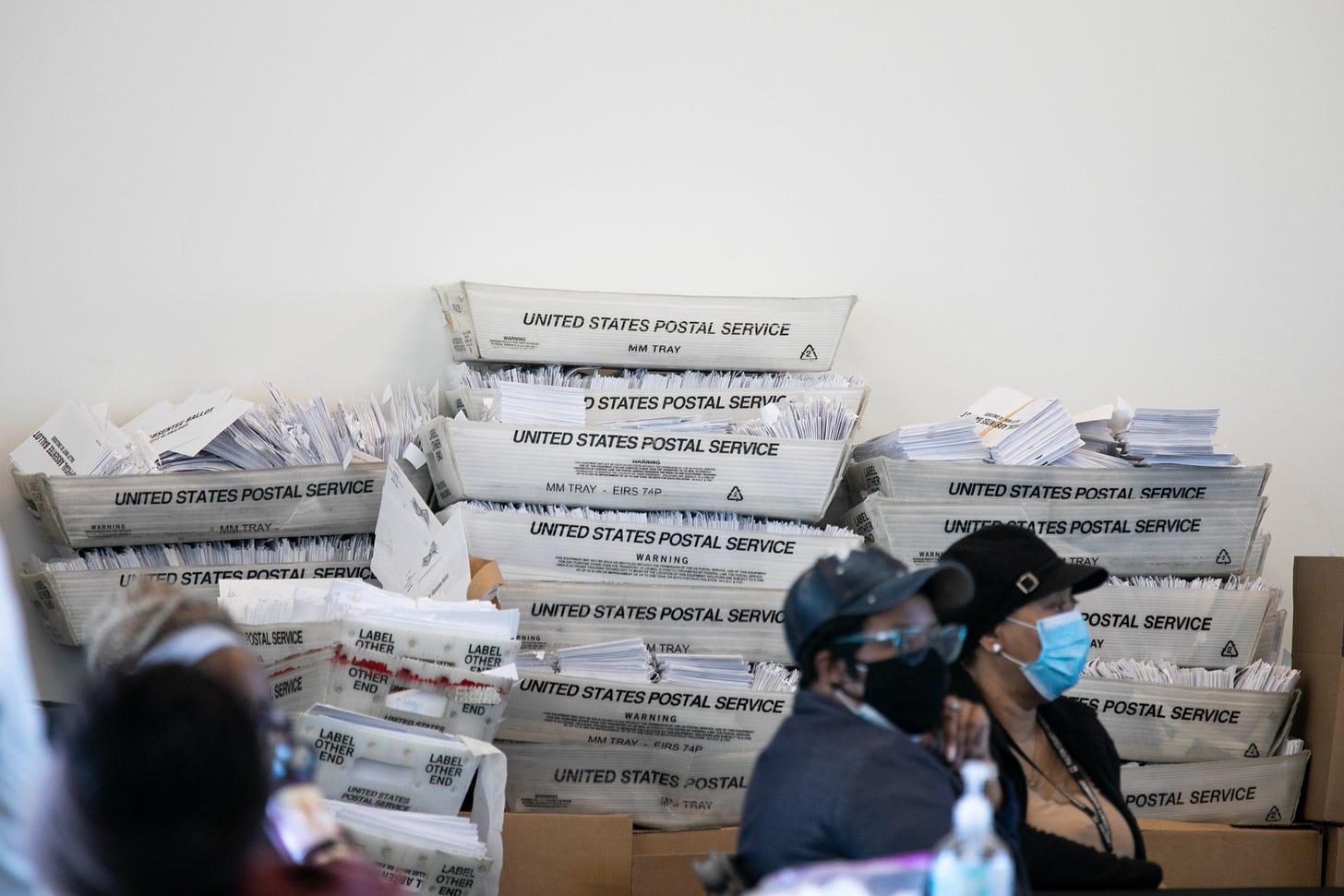

“That’s we’re [sic] the fraud will begin,” another group member responded. “With mailing out ballots. Then we will have dead people voting and illegals just like in the presidential election.”

Several academic studies and journalistic efforts have shown that these allegations are unfounded.

Stanford researchers, for example, studied universal mail-in voting in Washington state. In a report last year, they said cases of voter fraud in which someone allegedly cast a ballot on behalf of a deceased person were “extremely rare.” The cases made up about 0.0003% of the more than 4.5 million votes cast in the state between 2011 and 2018, the study’s authors wrote, and even the few cases “may reflect two individuals with the same name and birth date, or clerical errors, rather than fraud.”

In a 2017 study, researchers at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School investigated “improper noncitizen votes” across 42 jurisdictions in 12 states and found that fraudulent voting by noncitizens accounted for 0.0001% of votes cast.

“The absence of fraud reinforces a wide consensus among scholars, journalists and election administrators: voter fraud of any kind, including noncitizen voting, is rare,” the authors wrote.

Heatlie, the recall leader, said he had concerns about the integrity of voting by mail in the past. “I was adamantly opposed to mail-in ballots, because they lend themselves more readily available for fraud,” he said.

False or unsupported claims may be diminishing trust in California’s upcoming recall election. Examples of those claims, from pro-recall Facebook groups, are quoted verbatim on the slivers of shredded paper.

Chronicle photo illustration from Getty Images elements

But, he said, in the current campaign, his approach to mail-in voting has taken a “180-degree” turn. “I’ve seen firsthand how apathetic and lazy the voting population is in California. … You have to make it as easy as possible for people to cast their vote otherwise they just won’t do it,” he said. “I’m for mail-in ballots. I think it’s going to make everything easier for people to cast their vote.”

Conspiracy theories about voter fraud exploded after the 2016 election, when Trump falsely claimed he won the popular vote. “Trump put this whole thing on steroids,” said Lorraine Minnite, a public policy professor at Rutgers University and author of the 2010 book, “The Myth of Voter Fraud.”

The same year, Trump’s adviser and friend Roger Stone helped introduce the slogan “Stop the Steal,” which became an organized campaign and a rallying cry at sometimes violent protests across the country in the aftermath of Trump’s loss in the 2020 election, including January’s storming of the U.S. Capitol.

“So what you get at the end is a solid base of extremism which is convinced of the illegitimacy of the 2020 election,” said Lawrence Rosenthal, the chair and lead researcher of the Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies. “And so, in order to maintain the credibility, the enthusiasm, or the emotional commitment of this movement, it requires consistent, repeated, non-stop assertions of misinformation.”

Posts of conspiracy theories about the recall are not unique to Facebook. The recall campaign has published unsupported claims on its website, RecallGavin2020.com, in the form of voter testimonials.

“DO NOT let it be like 2020 and the Biden steal. Act now, act hard, because if we don’t take California back NOW, it’ll be to late [sic],” wrote a recall supporter identified as “J From Orange County.”

Newsom “is from a family that is/was involved with the mafia,” wrote “Lori From Sonoma County.”

Heatlie told The Chronicle he was unaware of these testimonials and would look into them.

Speaking for himself and not the campaign, Heatlie criticized Elder, the leading Republican candidate, for incorporating conspiratorial rhetoric into his public comments. On Aug. 19, Elder tweeted an article from The Gateway Pundit, a far-right news site, that falsely claimed California’s mail-in ballot had features designed to facilitate fraud.

The ballot design elements discussed in the article are standard, a Chronicle fact check shows. For instance, a pair of small holes in the return envelope — described in the article as a scheme to allow Newsom backers to look inside and selectively discard pro-recall ballots — are tactile aids for visually impaired voters to indicate where to sign their names. They also serve as a visual check for elections officials to ensure a ballot has not been left inside an envelope uncounted.

Ying Ma, a spokesperson for Elder, told The Chronicle that the candidate was trying to “stimulate discussion” about the integrity and competence of the election process.

“Just because he posts something doesn’t mean he’s making an allegation,” Ma said. “We want to make sure every vote is counted.”

Minnite, the Rutgers professor, said misinformation about voter fraud and mail-in ballots is likely inspired, at least in part, by confusion surrounding recent changes to some rules and procedures. Many changes were introduced in 2020 to minimize the risk of voters contracting COVID-19 at the polls.

At least one recent change to the recall election process, though legal, was a political move that fueled doubts about fairness. Democratic lawmakers adopted new rules this summer that bypassed several steps in the recall certification process, allowing the election to take place at least a month sooner than it would have otherwise, a move seen as benefiting Newsom.

“I think what’s happened is the fraud argument got sort of woven into this other argument about the rules changing,” Minnite said.

Representatives from the campaign to stop the recall effort, led by Newsom, did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

The Secretary of State’s Office, which oversees elections, called voter discouragement the “biggest threat” posed by election-related conspiracy theories, and said it was working to “inoculate voters against election misinformation when it arises.”

“We believe misinformation draws from confusion and concern,” the office said in a statement, “so we try to meet that confusion and concern with accurate, transparent explanations to commonly misunderstood questions, like breaking down the security features of our voting systems or illustrating how to vote on a ballot.”

Romero of the Center for Inclusive Democracy said she didn’t expect major “Stop the Steal”-style protests if Newsom fights off the recall attempt, but said it would be “foolish to rule anything out.”

“I think the only thing we can say for certain is that if Newsom survives, the conviction will be widespread in this world that it happened because it was rigged,” said Rosenthal, the Berkeley researcher. “That’s almost a given.”

Kaylee Fagan is a Bay Area freelance writer. Email: metro@sfchronicle.com