Conspiracy theories cast a long shadow

Korey Rowe served tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and returned to the U.S. in 2004 traumatized and disillusioned. His experiences overseas and nagging questions about Sept. 11, 2001 convinced him America’s leaders were lying about what happened that day and the wars that followed.

The result was “Loose Change,” a 2005 documentary produced by Rowe and written and directed by his childhood friend, Dylan Avery, that popularized the theory that the U.S. government was behind 9/11. One of the first viral hits of the still-young internet, it encouraged millions to question what they were told.

While the attacks united many Americans in grief and anger, “Loose Change” spoke to the disaffected.

“It was the lightning rod that caught the lightning,” Rowe recalls. He had hoped the film would prompt a sober reassessment of the attacks. Rowe, who lives in Oneonta, N.Y,, doesn’t regret the film, and still questions the events of 9/11, but says he’s deeply troubled by what 9/11 conspiracy theories revealed about the corrosive nature of misinformation on the internet.

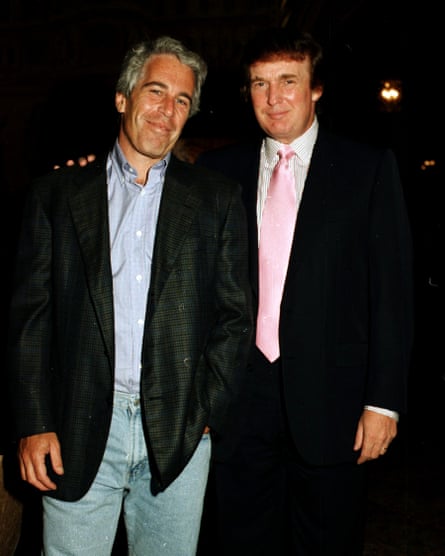

Twenty years on, the skepticism and suspicion first revealed by 9/11 conspiracy theories has metastasized, spread by the internet and nurtured by pundits and politicians like Donald Trump. One hoax after another has emerged, each more bizarre than the last: birtherism. Pizzagate. QAnon.

“Look at where it’s gone: You have people storming the Capitol because they believe the election was a fraud. You have people who won’t get vaccinated and they’re dying in hospitals,” Rowe says. “We’ve gotten to the point where information is actually killing people.”

There were, of course, conspiracy theories before 9/11 happened — John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the moon landing, a supposed 1947 UFO crash in Roswell, N.M. And the country’s interest in alternative, fringe theories was on the rise before 9/11, exemplified by the 1990s show “The X-Files,” with its taglines of “The truth is out there” and “trust no one.” But it was 9/11 that heralded our current era of suspicion and disbelief and revealed the internet’s ability to catalyze conspiracy theories.

“Conspiracy theories have always been with us, and it’s just the means of sharing them that has changed,” says Karen Douglas, a psychology professor at the University of Kent in England who studies why people believe such explanations. “The internet has made conspiracy theories more visible and easy to share than ever before. People can also very quickly find like-minded others, join groups, and share their opinions.”

Conspiracy theories about the attack and its aftermath also gave early exposure to some of the same people pushing hoaxes and unfounded claims about COVID-19, vaccines and the 2020 election, including Alex Jones, the Trump-supporting publisher of Infowars, who has accused the United States of plotting the attacks and has said the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting was a hoax. Jones was a co-producer of the third edition of “Loose Change.”

Polls show belief in 9/11 conspiracy theories peaked in the years immediately following the attack, then subsided. Repeated surveys show a small percentage of Americans continue to harbor doubts about the official explanation of the attacks.

It’s not surprising that such views persist, or that they have ebbed over time. Shocking, sudden events often spawn conspiracy theories as people collectively grapple with understanding them, says Mark Fenster, a University of Florida law school professor who has studied the history of conspiracy theories in America.

“A plane that runs into the World Trade Center? That runs into the Pentagon? It sounds like the stuff of films,” Fenster says. “It just didn’t seem like a real event, and it’s when you have a major anomalous event like this that conspiracy theories sometimes come around.”

Before the internet, conspiracy theorists relied on books, pamphlets and the occasional late night television show to espouse their beliefs. Now, they can swap theories on message boards like Reddit, post videos on YouTube, and win over new converts on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

The first known 9/11 conspiracy theory was put forward only hours after the attack, when an American software engineer emailed a post to an internet forum questioning whether the towers were toppled by a controlled detonation.

Twenty years on, a search on YouTube for content related to 9/11 turns up millions of hits.

Thousands of videos focus on conspiracy theories. That is a lot, but the grandfather of modern conspiracy theories has been outpaced by the upstarts: A Google search of “9/11 conspiracy theory” turns up more than 8 million results, while a search for “COVID conspiracy theory” turns up more than three times that.

Tech companies say they have done what they can to limit the spread of false information about 9/11. YouTube has added links to authoritative sources to some 9/11-related videos. Facebook says it has added fact checks to several viral hoaxes about 9/11, including one that the Pentagon was struck by a missile and not a plane.

For many younger Americans who came of age after 9/11, the internet is the first place they go for information on the event. Sept. 11 isn’t taught consistently in schools; some districts require it while others brush over it or ignore it completely.

False claims about the attacks often come up at the National Sept. 11 Memorial and Museum, which offers educational services to visitors and school children across the country. Such instances are an opportunity to talk about the facts of what did happen, and the many investigations that followed, according to Megan Jones, senior director of educational programs at the memorial.

“We have a generation now with no memory of 9/11, so it’s important to share the stories of what happened,” Jones says.

Bogus claims about the Sept. 11 attacks never posed the threat now ascribed to misinformation about COVID-19 or the 2020 U.S. elections. But even proponents of 9/11 conspiracy theories say questions about what happened primed the pump for the distrust and anxiety behind today’s conspiracy theories.

“The danger is, once you have that distrust of authority and government, it’s a dangerous place to be,” says Matt Campbell, a British citizen whose brother died in the World Trade Center on 9/11. Campbell believes the towers came down after a controlled demolition, and is seeking a new inquest in the U.K. that would review his brother’s death.

“If you think everything they’re telling you is a lie, then you just switch off: ‘Could be true, might not be true, whatever,’” he says.

On the grand scale, such beliefs can become dangerous when they begin to divide a society or when they are exploited by a political leader or an outside adversary.

“Usually it is the case that the people who feel they are being excluded from power who are committed to conspiracy theories,” Fenster says. “What’s different this time is that it was the party that was in power — the party that had the White House — that was the main broadcaster of conspiracy theories.”

Early on, conspiracy theories about Sept. 11 were popular with some liberals who disliked former President George W. Bush or who opposed the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. But after Barack Obama became president, bogus claims about 9/11 began growing in popularity among some conservatives who cite it as an example of the handiwork of the “Deep State.”

Ben Crew is a screenwriter who has produced a video debunking many popular 9/11 conspiracy theories. He’s also started a project in which he travels the country collecting personal accounts of 9/11, with the goal of getting at least one story from all 50 states.

Crew hears lots of conspiracy theories — claims about a missile hitting the Pentagon, claims that the airliners that hit the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and crashed in Shanksville, Pa., were empty.

He says that almost everyone he interviews considers 9/11 a pivotal point in U.S. history, the start of a wave of anxiety and fear that for many people hasn’t crested.